Photo by Stephen Lemons, illustration by Eric Torres

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s not hard to miss the small Arizona outpost of Seligman.

It’s a dot on the map about an hour west of Flagstaff – technically not a town but a “census-designated place,” a more complicated way of saying, “This place exists.” Home to roughly 450 souls, its only claim to fame is that it sits on historic Route 66, though it clings to only one of that famous highway’s 2,448 miles. A passing motorist could inhale upon entering Seligman and not have to let out a breath before rolling out the other end.

It’s also not hard to go missing in Seligman.

That’s what happened to Phoenix native Keith King just more than 19 years ago. On May 7, 2006, according to one account, the 46-year-old walked away from his girlfriend’s house in a T-shirt and flip-flops. He plodded over the windswept rocky terrain, dotted with pinyon and juniper trees, for a hike. Then he was never seen again. It was as if he’d been beamed up by one of the extraterrestrials he believed in and sometimes believed himself to be. A missing person’s case was opened and inquiries were made, but the mystery of King’s disappearance has remained unsolved.

But it certainly has not remained undiscussed. Seligman has a population of a small high school and can be every bit as gossipy. Theories abounded. King’s girlfriend, Karen Wells, was hardly a monogamist, and King was not the only beau in her life. Some of Wells’ other suitors had wives. In a tiny town, one wouldn’t have to dig very deep to strike upon some lingering resentment. Perhaps someone got jealous and then got violent. Perhaps, instead of disappearing, King was disappeared.

For much of the last two decades, theories were all they were. Wells died in 2023, leaving only her official account with the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office to go by. One popular suspect – another of Wells’ flames, a man whose wife had warned authorities about him – took whatever he knew to the grave earlier this year. The pool of suspects and potential witnesses was already small in Seligman. The passing years have drained it further.

However, one person is not content to let King’s disappearance fade into the past. King’s youngest daughter, Lindsey King, has resolved to uncover her dad’s fate.

In 2021, a private investigator named Kelley Waldrip began frequenting the bar at the Phoenix restaurant The Main Ingredient, where Lindsey worked at the time. He was simply seeking a watering hole, not a job. But King’s daughter convinced him to take up her father’s case. Waldrip began poking around, tugging on threads that had been untouched for years and unearthing new ones. Over a series of months, an alternate theory of what happened to Keith King began to form.

Lindsey King and Waldrip now think that he’s solved the case. They believe Keith King was murdered, and they believe they know who killed him and why. And perhaps most importantly to proving all this, they believe they know where his body is – chopped into pieces and stuffed into a septic tank that’s buried on a property in Seligman.

All they need, they say, is for the county sheriff’s office to dig it up.

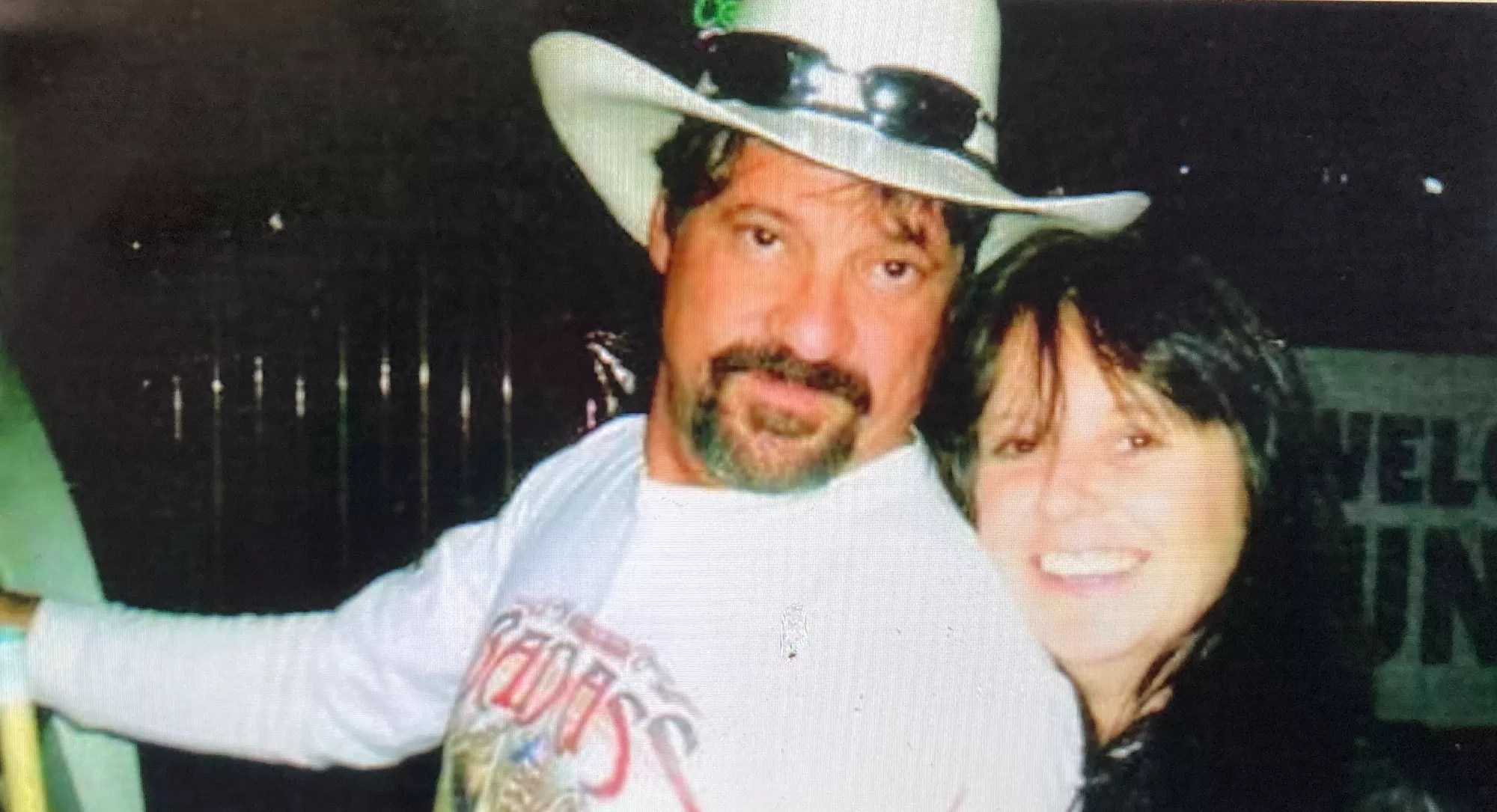

Keith King with one of his daughters, decades ago.

Courtesy of Lindsey King

‘Luminous beings’

Lindsey King was 18 when her father disappeared.

Sitting in shorts and a T-shirt in her central Phoenix bungalow one recent spring day, her large brown eyes occasionally teared up while talking about her dad. More than half her life has passed since Keith King vanished – Lindsey is now 37 – but her mind turns often to her father.

“There hasn’t been a day in my life that I haven’t thought about my dad,” she said.

Lindsey’s parents divorced when she was six, but her memories of her father are largely positive. For her ninth birthday, he hired a limo to ferry her and her friends to the Great Skate roller rink in Glendale. That same year, she joined him for Bring Your Daughter to Work Day at Sands Chevrolet, where he was a sales manager. She got to drive a golf cart, almost crashing it into one of the cars on the lot.

She remembers him as funny and cool and successful, living in a condo at the Pointe Hilton, driving a Corvette and riding a Harley. He listened to Jewel and Jimmy Buffett and boasted that he planned to be a millionaire by age 50. In a separate interview, Lindsey’s younger brother, Riley, described Keith as “spontaneous.” Keith had a pet sugar glider and lavished his youngest son with “all the good toys,” Riley said – a Nintendo 64, a dirt bike, a BB gun.

“He was always fun to be around,” Riley recalled, “but unfortunately, there wasn’t enough time to really understand who my dad was.”

Keith disappeared when Riley was 14. Even before that, though, the dad he knew had begun to slip away. Years before his disappearance, Keith suffered a mental collapse, plagued by delusions and isolating himself from society. One Christmas Eve, Lindsey recalled, he showed up in a trench coat and dark glasses and “was obsessed with ‘The Matrix.'” He gave her a gift and told her it was from “The One to The One.”

A psychiatric evaluation of Keith, performed by West Yavapai Guidance Clinic in 2003 and shared with Phoenix New Times by Lindsey, diagnosed him with psychosis and said Keith “would qualify for disability.” He’d moved to Prescott from Phoenix and became increasingly solitary, stating that he couldn’t “mix with people.” The psych evaluation was the first time he’d left home in a month.

Keith told the evaluator that his life changed one day when he looked through binoculars and saw UFOs and “luminous beings” that were “transparent with a greenish color.” He was paranoid that people, including his second wife, were trying to poison him. To avoid illness, he’d drawn a Pac-Man on his hand – the ravenous video game character would “go through my arm and get all the negativity out of my body.”

He admitted to abusing cocaine, meth and alcohol in the past, but told the doctor that he was sober. According to his children, Keith’s sobriety was less than constant. Lindsey said her father “dabbled with” meth all his life. Her aunt, Kelly King, called Keith a lifelong “fan of alcohol and drugs.”

It was “through drugs,” Lindsey believes, that Keith met Karen Wells. They’d first met in Prescott, but eventually moved to Seligman in 2005, where Keith lived in an RV on a 40-acre property owned by Wells’ parents a few miles south of town. Then one day, Keith walked out of the RV and, underdressed for the terrain, supposedly lit out for a hike. He was never seen again.

At least, that’s what Wells claimed.

Keith King and Karen Wells in the mid-2000s.

Karen Wells’ cellphone

Love triangle

Not long after Keith went missing, there were hints of a more nefarious fate.

The next day, Wells filed a missing person report with the county sheriff’s office. She told deputies that she’d last seen Keith the previous morning in his RV in flip-flops, a T-shirt and gray pants. He was about 170 pounds and 5-foot-10 and wore a mustache. Keith was “psychotic” and had refused to take his meds, she told them. He also “believed he was an alien.”

Keith had been reportedly spotted two other times before he vanished, according to the sheriff’s office report. At about 5:10 p.m. the day before Keith disappeared, an Arizona Department of Public Safety officer spotted him in a parking lot near his truck, which had been towed after conking out on a railroad track west of town. A Seligman man named Bill Wilkins told deputies that he’d seen Keith roughly 11 hours later, walking near a Chevron station. Wilkins had given him a ride home.

Then the investigation got weird.

Keith and Wilkins had a complicated history. Chris Vasiliow, a longtime friend of Keith’s, told deputies that the two men had been involved in a love triangle with Wells. Wilkins, who was separated from his wife, knew Keith was dating Wells, and vice versa. Wells told sheriff’s deputies that King and Wilkins were “friends” with no issues between them.

But Wilkins’ estranged wife apparently felt her husband was dangerous. On May 15, eight days after Keith went missing, Patty Wilkins came into the sheriff’s office substation in Seligman. She’d learned her husband was seeing Wells, she told deputies, and he’d become angry. If Patty disappeared, the sheriff’s office report says, she “wanted to make sure we knew where she lived and that we would not stop looking for her.”

Holes also began to form in Wells’ account. She told deputies she’d retrieved King’s wallet from his truck, only to later claim that he left his wallet, cell phone and checkbook in his RV. Wells, who had done two years in prison in the early 2000s for multiple drug violations, also claimed others had seen Keith since he vanished. Those sightings never panned out.

Not long after Keith disappeared, a helicopter search was conducted. It turned up nothing. Later, a search and rescue team scoured Seligman and beyond with cadaver-sniffing dogs. No body was found. According to the police report and relatives, the King family tirelessly drove up to Seligman to paper the town with posters and even employed psychics to aid in the search.

These efforts proved futile. In 2009, three years after anyone had laid eyes on Keith King, the sheriff’s office declared the case closed. Closed it has remained, gathering dust in the files of the county sheriff’s Cold Case Unit.

Then, 12 years later, a private investigator began frequenting The Main Ingredient.

Lindsey King (left) met private detective Kelley Waldrip (right) while she was working at The Main Ingredient in Phoenix.

Danielle Cortez

Enter the shamus

Kelley Waldrip was just looking for a place to bend his elbow.

A Phoenix native, the 72-year-old Waldrip had enjoyed a long and distinguished career in law enforcement. He’d been an investigator for the U.S. Navy’s Naval Criminal Investigative Service and had served as an intelligence analyst for the FBI. He then worked as a private dick in Los Angeles for many years before semi-retiring and moving home to Phoenix.

Rail thin, with a hang-dog look that belies a biting wit, Waldrip has seen it all, doing investigations for NCIS in places like Thailand, Haiti and Saudi Arabia. He started his career as a cop with the Glendale Police Department and later became a deputy at the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, where he came to loathe Sheriff Joe Arpaio. Before leaving the sheriff’s office for NCIS, Waldrip became a whistleblower, alerting the press to the corruption of Arpaio’s reign, earning him a permanent place on the sheriff’s enemies list.

Seeking an alternative to his preferred watering hole, Durant’s, Waldrip stumbled upon the bar at The Main Ingredient, where Lindsey managed the restaurant and sometimes filled in as bartender.

“I was a regular customer at The Main Ingredient,” Waldrip told New Times. “Word got around, probably because I mentioned it, that I was a private investigator. And one night, Lindsey approached me and said, ‘Hey, maybe you could find my missing father.'”

Lindsey had been haunted by her dad’s unknown fate. She’d learned of his disappearance while a senior in high school, when a cousin told her Keith had been missing for two weeks and was presumed dead. Lindsey’s family wanted to keep the news from her until after graduation. As an adult, she asked for and received the family’s file on the disappearance, waiting on the right bit of information – or the right person – to crack the case.

Waldrip was that person. He craves a challenge and took on the case pro bono.

His first move was to obtain the county sheriff’s report on the disappearance. King’s family also supplied him with information, including notes from another private detective, Jack Locarni, whom the family hired in 2006 out of frustration with the official investigation.

Locarni’s notes added some shading to the mystery. Vasiliow, Keith’s good friend, had told the P.I. that it wasn’t unusual for King to take off for weeks at a time without telling anyone. Given that, Vasiliow thought Wells “was very quick” to report Keith missing.

Locarni also interviewed Wells and Wilkins at the Seligman discount store where they worked. They acknowledged they’d been “seeing each other” for several weeks, but Wilkins claimed their relationship was platonic and “hinted he was incapable of having sex.” Both repeated versions of what they’d told deputies.

Locarni later talked to Wilkins’ estranged wife. Patty Wilkins said she’d put up missing posters for King, but that Wilkins had told her to remove them because Keith was in touch with his family. (Keith was not.) Wilkins told Locarni that his wife was mistaken – he told her to take down the posters because no one would recognize Keith from the photos they featured.

Locarni came to no conclusions. But according to the sheriff’s office report, he told deputies that he believed King died “due to suspicious circumstances” and that he had a “bad feeling” about Wilkins.

Waldrip had a similar impression, at least initially. A year ago, he traveled to Seligman to speak with Wilkins. In his report, which he shared with New Times, he described Wilkins as hostile and said his recollections relating to Keith’s disappearance were contradictory. But that might be explained by Wilkins’ dementia, a condition his daughter confirmed to New Times.

Wilkins died earlier this year at 81. Patty Wilkins is still alive but not well enough to be interviewed, her daughter said.

Wells is also dead, having succumbed in 2023 to emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia. But Waldrip spoke with her daughter, Brenda Lindsay, by phone. She remembered Keith, she said, who her mother told her had “just disappeared.”

Later that same day, Brenda called again. Crying, she claimed she had just learned the truth. But she couldn’t speak freely in Seligman, she said.

Waldrip made plans to meet her in Phoenix.

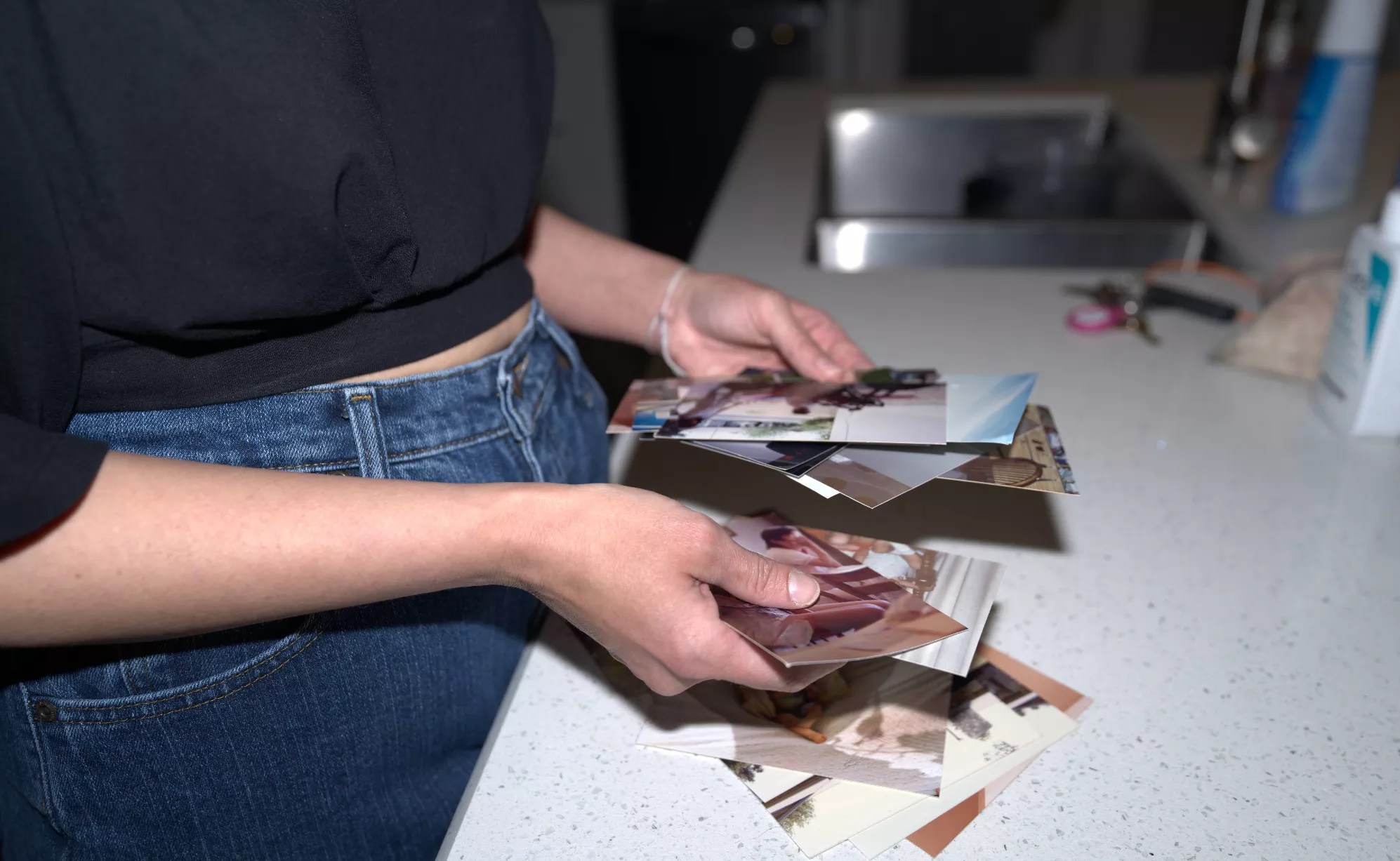

Lindsey King thumbs through old photos of her dad.

Danielle Cortez

Septic tank sayonara

Sitting in Waldrip’s apartment days later, Brenda served up the first new lead the case had seen in years.

After first speaking to Waldrip on the phone, she’d told a longtime friend of her mother’s that a private detective was sniffing around. The woman suddenly asked if Keith’s body had been found. The woman then told Brenda about a tearful, “out of the blue” confession Wells had made to her while they watched TV one night in the months leading up to Wells’ death. The woman later repeated the story to Waldrip.

Wells allegedly confessed the following to her friend: The night before Keith disappeared, Wells was in her home south of town when she began arguing with yet another boyfriend – a married man, but not Wilkins. Keith heard the commotion and walked from his RV into the ruckus. Keith threatened to out the man to his wife and then turned to leave.

The man then shot Keith in the back, killing him. He then forced Wells to help him chop up Keith’s body and dispose of it in a septic tank on the property.

New Times interviewed Wells’ friend, who asked not to be named out of fear for her safety. She claimed Wells had sworn her to secrecy until after her death. Wells maintained a relationship with Keith’s alleged killer, the friend said, but was “scared” of him. The friend claimed to have once heard Wells and this man arguing about money, with Wells threatening to expose their relationship to his wife.

Asked if she would repeat her story to the police, the woman said she didn’t know. She didn’t want the man “coming after me, chopping me up.”

Brenda was also aware of her mother’s affair with the man. “My mom really had a thing for married guys there for a while,” she told New Times. She knew her mom was afraid – Wells hid knives in her trailer in case she had to defend herself – and Brenda believed she harbored a dark secret.

“I remember very vividly her telling me, ‘You have no idea about the nightmares that I have,'” Brenda said. “‘You have no idea about the things I’m trying to deal with inside my head.'”

Unlike most of her mom’s boyfriends, Brenda liked Keith. “A little crazy, but not in a bad way,” she recalled. “He was definitely the best boyfriend that my mom ever had.” She’s bonded with Keith’s daughter, passing along information about their respective parents. But since hearing of her mom’s alleged confession, she believes she and Lindsey King have more in common than they’d prefer.

Brenda now suspects foul play in her mom’s death. Wells died two hours after returning from a five-day stint in the hospital, she said, and she didn’t seem ready to die. Shortly before she passed, she texted “911” to her daughter, who lived in the trailer next door. By the time Brenda saw it and checked on her, Wells was dead.

The county didn’t perform an autopsy, and Brenda didn’t have the money to pay for one. Wells was cremated. Brenda now wonders if her mother was silenced – Wells had always left her trailer unlocked.

When asked about her willingness to go on the record with her suspicions, Brenda offered New Times a warning.

“If I disappear,” she said, “it’s not because I wanted to.”

Theresa Higdon, a volunteer investigator with the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office, said the county is a well-known “dumping ground” for the corpses of victims murdered elsewhere.

Stephen Lemons

Desert dumping ground

New Times contacted the man at the center of Wells’ confession. Because he has not officially been accused of wrongdoing in what is still considered to be a missing person’s case, New Times is not revealing his name.

Garrulous and amiable, the Yavapai County man spoke to New Times in person for more than an hour. The rambling interview covered a wide range of topics, including true crime television shows, classic cars and serial killers. Shown a photo of King and Wells together, he said he wouldn’t know King “if he stepped on my toe,” though he admitted that he was familiar with Wells and with Bill Wilkins and knew the pair had dated.

Asked about speculation that Wells and Wilkins may have had something to do with King’s disappearance, he was doubtful. “She didn’t seem like that kind of person,” he said. “And Bill – I certainly didn’t think he was going to go kill someone over her. But you never freaking know.” He did agree that the circumstances of King’s disappearance, as related by New Times, sounded “suspicious.”

“If he went on a hike and died, somebody would find him,” he said. “That doesn’t make sense, you just walk out there and disappear.”

The man denied having anything to do with King’s disappearance. He said that he and Wells had just been “friends,” though text messages obtained by New Times may suggest otherwise.

Those messages come from Wells’ iPhone and laptop. Dated from 2020 to 2023 – many years after Keith disappeared – they only hint at a relationship and its nature. The man wrote that a photo of Wells at the Black Cat Bar was “hot.” She called him “honey.” She complained about her health and money, and he sometimes offered to help financially. They discussed meeting each other. Wells sometimes got angry with him.

“I’m not going to be in the middle of someone else’s relationship!” Wells once texted the man. “I deserve better!!! If you are unhappy… change your life!”

“I’ll talk to you tomorrow,” the man wrote back stoically.

Brenda said that after she spoke to Waldrip, she got a call from someone at the sheriff’s office asking if she could bring her mom’s devices to its headquarters in Prescott. She didn’t have a working car, so they asked her to drop them off at the Seligman substation. She balked – Seligman is such a small town, an act of flatulence is like the shot heard round the world.

“There’s no way I would drop off anything that I wanted to have taken serious to the cops up here,” she said. “I just wouldn’t do it because it’s all about who you know and who you are.”

Instead, Brenda gave the devices to Keith’s daughter, who shared them with New Times.

Waldrip said he sent his reports of what he’d uncovered – including the tale of the septic tank and the news that Brenda had Wells’ devices – to the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office. They seemed to garner little interest until he wrote directly to Sheriff David Rhodes about the case.

In 2024, he said, he met with volunteer investigator Theresa Higdon and Detective Sergeant Charles Owens, her supervisor. Waldrip said Owens was “defensive” and explained how difficult it would be to remove a septic tank from the property where Keith was last seen.

Higdon and Owens also met with Lindsey King earlier this year. Owens assured her that her dad’s case was on the “front burner” and said Waldrip had brought up some good points. The case had been in disarray, he noted, but the investigation was again moving forward.

In an interview with New Times, Higdon said the sheriff’s office welcomed Waldrip’s research but was still trying to “validate” it. Officially, the investigation is still a missing person’s case, not a homicide inquiry. Higdon complained that the cold case unit is often hampered by the fact that Yavapai County is a well-known “dumping ground” for the corpses of victims murdered elsewhere. She said the Keith King case is one of 50 to 75 currently being worked by her unit.

She said she was aware of the septic tank theories, but she did not say whether the sheriff’s office had plans to dig one up.

Lindsey King doesn’t feel that the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office is acting with enough urgency to solve her dad’s disappearance.

Danielle Cortez

The haunting

Those septic tanks may hold the key to finding Keith, or what’s left of him.

According to documents on file with the Yavapai County Recorders’ Office, Wells’ parents sold the property that holds them in 2023. On a recent visit to Seligman by New Times, Brenda pointed to the area behind the house where Keith had parked his RV. There were two septic tanks on the property, one for the house and one for a dilapidated mobile home out front.

Jacob Stelljes now owns the property. He confirmed that there were two septic tanks on the property, only one of which had been pumped. He told New Times that he granted sheriff’s deputies access to his property five or six months back, but “nothing came of it.”

Lindsey King said that in her meeting with Owens last year, the sergeant said that in order to obtain a warrant to unearth the septic tanks, he first needed to develop probable cause. Speaking recently by phone to New Times, Owens declined to comment on the status of the investigation.

As for the septic tanks, he said digging them up could connect the dots or reveal nothing – even if Keith’s body was actually dumped in them 19 years ago.

“In my experience, most of the flesh would be gone,” Owens said. “But depending on the chemicals and the things inside the septic tank, we could expect to possibly recover bone material or bone fragment material and be able to analyze that.”

The Cold Case Unit that Owens oversees has scored some successes, cracking two unsolved murders in and near Prescott. In 2023, the unit reportedly helped solve the 1987 murder of 23-year-old college student Cathy Sposito. And in 2020, a cold case volunteer helped solve the 1980 shooting death of Michael E. Lee outside of town.

Owens acknowledged the King family’s frustrations and asked for patience. Cold cases are difficult to investigate, he said. “People get older, they forget minor details, and in a cold case, it’s the minor details that point us into the direction of where to go,” he said. In Keith’s case, several principals are dead.

But Lindsey King remains skeptical. In a follow-up interview on the patio of The Main Ingredient, Lindsey said she found Higdon and Owens to be “trustworthy” but felt they were giving her conflicting messages. They asked her to be “patient” while harping on how complicated and expensive it would be to dig up a septic tank.

“‘We’re not going to go into this until we have a smoking gun,’ is how they were trying to present it to me,” she said. “I don’t feel they’re doing anything more than has been done before.”

She wants more giddy-up-and-go from the sheriff’s office, particularly when it comes to the tanks she’s convinced hold her father’s remains. The issue is not a new one. Though the sheriff’s office has been responsive of late, the King family has long complained about the office’s lack of interest in the case.

In a 2007 letter to an attorney, Linda King – Lindsey’s grandmother and Keith’s mom – detailed a series of perceived missteps and displays of indifference on the part of the sheriff’s office, concluding that its investigators didn’t care because “Keith had been a drug addict from time to time.” Lindsey made the letter available to New Times. An ordained minister in the Church of Science of the Mind, Linda King died in 2019 at 81. She never learned the fate of her son Keith, the fourth of her six children.

Keith’s ghost doesn’t just haunt the King family. Employees at the Seligman outposts the Black Cat Bar and the Roadkill Cafe recalled seeing Keith and Wells together and the missing person posters the family put up when Keith vanished. One waitress told New Times that after Keith disappeared, Wells and Wilkins were seen together and tongues wagged, suggesting the pair had offed him.

Lindsey said that initially, her main goal in partnering with Waldrip was to find out what happened to her father and possibly recover his remains. Ideally, she’d like the sheriff’s office to pump the septic tanks, do a criminal investigation and seek the prosecution of her dad’s killer. But she knows that justice is elusive and that she may never be able to prove who murdered her dad.

Still, she wants to send a broader message to the person or persons who may have taken her father’s life: That he was not garbage. And that he’s been sorely missed.

“I want the person who killed my father to know that he had kids and that his life was valuable, and it meant something to me,” she said. “It felt like he was just thrown away or something. My dad deserved a lot better than that. I want people to know he was loved.”