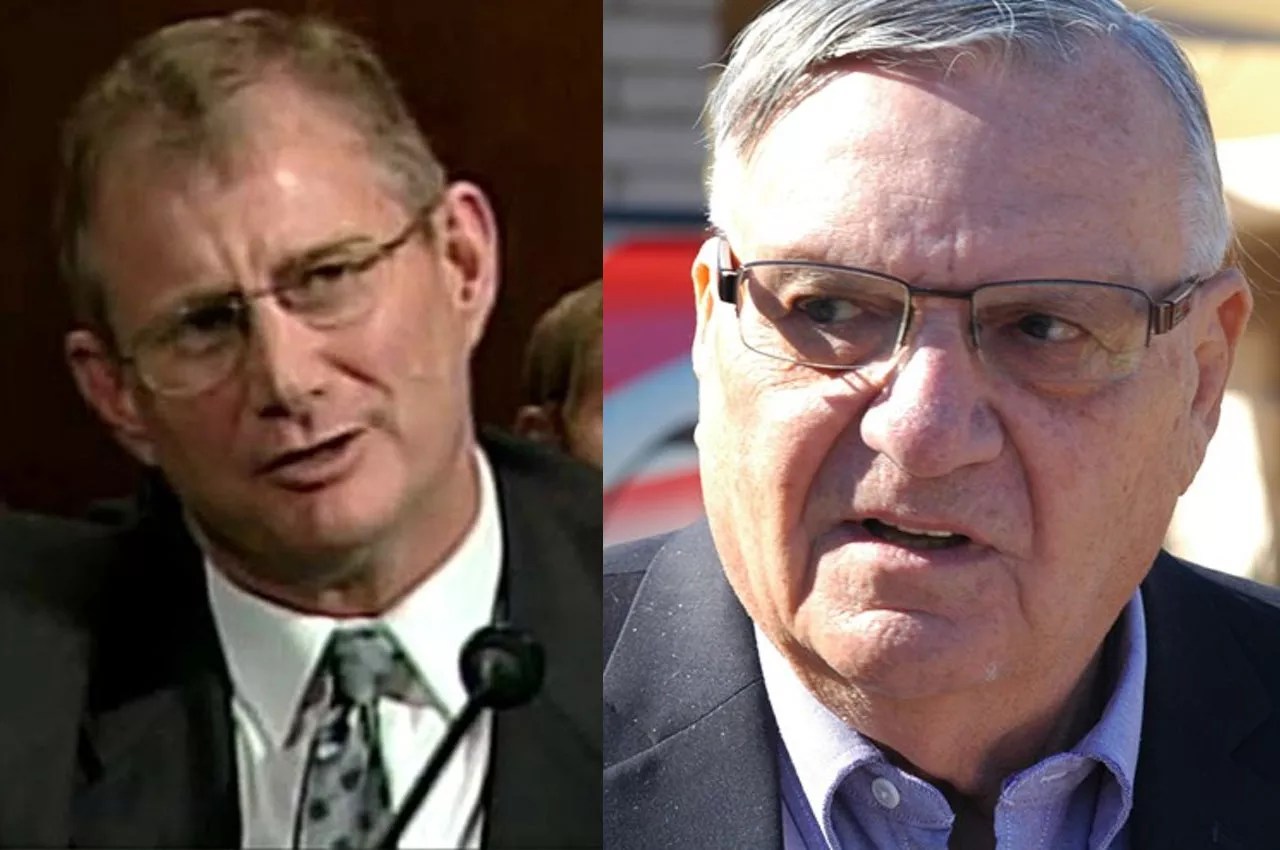

Snow: CSpan/ Arpaio: Stephen Lemons

Audio By Carbonatix

U.S District Court Judge Susan Bolton sat through nearly three hours of closing arguments Thursday in the trial of former sheriff Joe Arpaio on criminal contempt charges and summed up the entire case in one question.

“Clear and definite to whom?” she asked, interrupting the final presentation by the federal prosecutor John Keller.

Keller was trying to prove that a 2011 court order by U.S. District Judge Murray Snow was clear and definite, that Arpaio knew about it, and that he willfully violated it.

Then Bolton again interrupted Keller’s closing argument to put her finger on the pulse of the one-week non-jury trial.

“Where do you get the evidence?” Bolton asked, that the sheriff told commanders and deputies at the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office how to react to the order.

The entire case hinges on what Arpaio knew, when he knew it, what he ordered, and if he understood the legal implications of the court’s order and his subsequent decisions.

The government argued that Arpaio knew all along that he was violating for 17 months an order to stop detaining people based solely on their immigration status when his deputies continued arresting such people and turning them over to the U.S. Border Patrol.

But Arpaio’s lawyer, Dennis Wilenchik, told Bolton there was not a single piece of evidence that Arpaio thought he was violating the order, that he ordered anybody to do so, or that he interfered with anyone who tried to comply.

Instead, he shifted blame on MCSO’s hired attorney Tim Casey for fumbling his advice to the six-term sheriff and to MCSO staff. He said Arpaio, who is now 85, delegated responsibility and those under him failed to follow through.

Bolton ended the hearing Thursday by ordering lawyers to submit written briefs on points of law by July 21, claiming, “There is no urgency.”

The final day of courtroom action highlighted the contrasting styles of Wilenchik and Keller as well as their drastically different interpretations of Arpaio’s predicament.

Keller, in his 90-minute closing summary, said Snow’s preliminary injunction on December 23, 2011, made it clear that MCSO had to have probable cause to arrest someone on state charges, and could no longer hold anyone based only on their immigration status.

He said that Casey advised Arpaio and his team that the language meant they had to arrest or release undocumented immigrants and that MCSO’s policy of turning them over to the federal authorities never changed until Snow issued a permanent injunction in May 2013.

“He didn’t care about the order. He didn’t care if he had hostile plaintiffs (in the class-action civil rights lawsuit that led to the order). He didn’t care if he had a hostile federal judge,” Keller said. “As a result, at least 170 people were turned over to federal authorities, in violation of the preliminary injunction and in violation of the law.”

Keller marched through Arpaio’s own statements under oath in previous court hearings, in MCSO press releases, and in television interviews. He played the tape of Arpaio telling one TV crew in April 2012, “Nobody’s higher than me. I’m the elected sheriff.” Another video from that summer showed him telling Fox News, “I’m saving the country and the world.”

The federal prosecutor also played Arpaio’s words off his deeds. He presented a series of internal MCSO tracking reports that documented how many people deputies had arrested and turned over to ICE who were not suspected of breaking any state law. Keller said that it continued month after month.

He quoted Arpaio on the stand saying there was no difference between the preliminary court order and the final one. Then he quoted a one-sentence directive from Arpaio after the final court injunction in May 2013. In it, Arpaio ordered, “no MCSO personnel shall detain any person for transfer to ICE unless probable cause to arrest or detain exists under Arizona criminal law.”

Keller’s conclusion: Arpaio knew exactly what Snow’s injunction meant, and the only thing that changed was that, now, he wasn’t seeing re-election for another three years.

Defense attorney Dennis Wilenchik said there’s not a single piece of evidence that Arpaio knew he was violating court order.

Stephen Lemons

The prosecutor’s presentation was logical, methodical, and clear on Thursday. It differed from his performance on the first day of trial, when he appeared thrown off, or even underprepared, in his efforts to question Casey on the stand amid near constant objections.

By contrast, Wilenchik appeared in his element thinking on his feet during his opening arguments, assertively and sometimes sarcastically trading barbs with Casey, peppering him with questions aimed at impeaching his credibility. But in his closing arguments Thursday, Wilenchik at times rambled and was hard to dissect and repetitive.

The underlying message was clear, though.

Nobody at MCSO understood Snow’s December 2011 order, nobody explained it to Arpaio or his commanders, nobody made sure they followed through, and nobody said or thought they were violating anything.

Wilenchik explained the reversal in May 2013.

“Why suddenly was the permanent injunction followed? Because it was clear then,” he argued. “The light went off. They understood. The order was clear and definite and understood by everyone.”

By contrast, he argued, the earlier order was subject to interpretation. He played an audio clip of judges on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals wrestling with the wording, concluding it will all become clear in a few weeks.

“What witness testified in this case that the preliminary order was clear and definite? Gee, I can’t remember any,” Wilenchik argued, noting even Casey, who appeared as the government’s witness, testified it was “ambiguous.”

Instead, he argued, Casey added to the confusion.

“He dropped the ball. He fumbled,” Wilenchik said. “Why wouldn’t a good lawyer seek clarification before exposing his client to possible contempt?”

“Not one note to his file has been produced by the entire power of the federal government saying, ‘I’ve got concerns about what was going on here. I think the sheriff is in violation,'” Wilenchik told the court.

Rather, he presented his client as ignorant. He suggested no evidence was offered showing Arpaio even read the order. Instead of ordering his deputies what to do, they advised Arpaio of how they were interpreting the court-imposed restrictions on traffic stops, having read it themselves.

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand why the sheriff couldn’t rely on those people to do it for him. And that’s what he testified. Did he have a right to expect it? Yes,” Wilenchik said.

He pointed to a discussion to circulate training guidelines, which never went out. When the command of the HSU changed, nobody briefed the incoming squad leader about the court order.

“Is that this man’s fault?” Wilenchik said, turning to point at Arpaio. “He’s the only one left holding the ball? He’s the only one standing here being held responsible?”

The argument was aimed at creating reasonable doubt that Arpaio willfully violated the law. Instead, he thought he was following it by cooperating with federal authorities, the defense argued.

Throughout the trial, Arpaio sat stoically, following arguments closely, occasionally looking down or holding his chin in his palm. He was his usual self, chatting and joking with reporters during breaks.

The packed courtroom reflected the community outside and its divisions over Arpaio’s legacy. Behind him sat a largely older and white group of supporters and some longtime MCSO brass. Latinos and community activists mostly filled the other side of the courtroom. About a dozen protesters assembled outside the glass Sandra Day O’Connor U.S. Courthouse with banners and placards denouncing Arpaio.

Scattered throughout the benches of the courtroom, and even on the floor, sat more than a dozen journalists – a large contingent for a Valley courtroom hearing – on hand to witness the spectacle that often follows Arpaio.

The spectacle never lived up to the hype. The only real fireworks were during the recess over the Independence Day holiday.

Now the action shifts to Judge Bolton’s chambers. She will review the evidence and legal arguments and make a ruling. She decides innocence or guilt, and if guilt, then the appropriate penalty. Arpaio could face up to six months in jail, but legal experts say that possibility is remote.

It may be weeks before the curtain falls on this chapter of the Sheriff Joe Show.