Mario Tama/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

Housing in the Valley is booming, not that most of the people who live here are benefiting from it.

Phoenix-area residents don’t have to travel far to catch the telltale signs of home construction. Throughout the Valley, glitzy new apartment complexes are going up on what used to be empty lots. On the ever-expanding fringes of Maricopa County’s urban sprawl — Goodyear and Buckeye to the west, Gilbert to the east, everything above State Route 101 to the north — civilization is arriving in the form of new developments filled with large, spacious single-family homes.

Arizona has a major housing shortage — we’re shy at least 120,000 units, per the Common Sense Institute — but surely the ubiquitous sight of cranes and cement trucks represents a turning of the tide. Indeed, the Valley is building with relative abandon. A January study by the Georgetown University Center on Poverty and Inequality found that new housing units (specifically, those built from 2010 to 2023) represent nearly 15% of the housing stock in the Phoenix metropolitan area. For the U.S. as a whole, that average is 11.4%.

The housing is being built. So why is it so damn hard to find an affordable place to live?

That’s the question the Georgetown study set out to answer. The study, titled “Abundance for Who?” — ahem, whom — looked at six major metropolitan areas that have produced more new housing than the national average since 2010. Phoenix made the list, along with Dallas, Houston, Seattle, Atlanta and Washington, D.C. The Georgetown analysis found that while those cities are producing plenty of new housing, that housing seems geared toward a certain well-heeled slice of the income spectrum.

In the 1980s, two-thirds of new “owner-occupied units” — read: single-family homes — had three or fewer bedrooms. From 2010 to 2023, however, more than 58% of new homes had four bedrooms or more. The inverse has been happening in the rental market. From 2000 to 2009, nearly 72% of new apartments had two or more bedrooms. Since 2010, 44.3% of new apartments were one-bedrooms or studios.

If you’re a family looking for a home, the market is serving up two unworkable options. You can choose a huge, fancy house that is out of your price range. Or you can cram into a tiny new apartment aimed not at families but at young, professional (and childless) renters.

“New houses for ownership keep getting bigger,” said Liz Hipple, the managing director of policy and research for the Georgetown Center. “It also suggests that there’s going to be a mismatch between the supply and families’ needs. A small studio in an apartment building may be the right thing for you earlier in your life, but if you want to have a family, you’re going to need more space.”

That’s certainly the case in Phoenix, with its booming suburbs and its glut of new apartment construction. Very little of the new housing is actually serving the large segment of the population that is getting pinched by the affordability crisis.

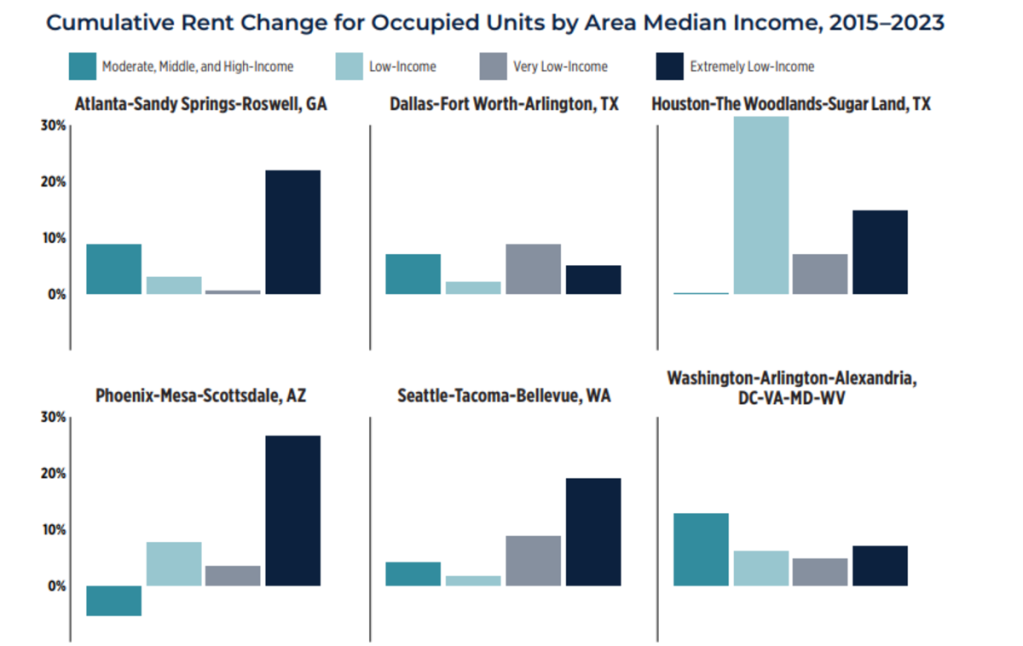

When the Georgetown study looked at trends in rent increases in Phoenix, it found that rent for moderate-, middle- and high-income renters went down 5.3% since 2015. But for extremely low-income renters, rent spiked by 26.7%. According to a study by Construction Coverage, the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Phoenix is $2,004 in 2026. The median household income in Phoenix at just north of $81,000 in 2024, per U.S. Census Bureau data, meaning a family making that much would spend roughly 30% of its income just on rent. The average rent for a three-bedroom apartment in Phoenix — $2,672 — would eat up nearly 40% of what the median-earning family would make in a year.

No wonder Maricopa County has seen its most eviction filings ever in the past two years.

Georgetown University Center on Poverty and Inequality

The problem

Why is the market churning out housing that doesn’t actually meet the demands of the market? You might be tempted to blame the builders. But you’d be wrong, says Nicole Newhouse, the executive director of the Arizona Housing Coalition.

“It’s easy to say it’s the greed of the builders, but it really isn’t,” Newhouse said. “It’s about construction math.”

When the market is left to work on its own, she said, it builds big houses and big complexes with tiny apartments. When building a house, it doesn’t cost all that much more in materials and labor to add an extra 2,000 square feet, but those larger homes can sell for way more. As for apartment complexes, developers have little incentive to build affordable units when higher-end apartments will generate more revenue. After all, the cost of building them is pretty much the same either way.

In Phoenix, the market is so unbalanced that new, high-priced housing keeps coming online, even though there aren’t enough people to buy or rent it. The Georgetown study found that 9.4% of housing units built in Phoenix since 2010 are sitting vacant, a higher rate than for older homes. In fact, Phoenix had the highest new-unit vacancy rate among the cities the study examined. Builders would rather wait for deep-pocketed renters or homebuyers than build homes for families on tighter budgets.

“A lot of them end up sitting empty because the landlords would rather rent for an extremely high price than lower it to an actual market-clearing price,” Hipple said.

Who that housing is serving, Newhouse says, is often not Arizonans. The Phoenix area continues to be a draw for people moving from higher-cost states like California and Illinois. For them, Arizona is an affordable paradise, where their Southern California home equity can buy a huge home in the suburbs.

But for people who have lived in Arizona for years, the state is getting more expensive, not less. Starter homes bought pre-pandemic, when interest rates were incredibly low, have become forever homes because the cost of getting into a bigger house is prohibitive. And those looking for their first home now face prices and interest rates that are way higher than they were five years ago.

“What we’re seeing is that the market can’t produce, really, housing for anybody who makes, let’s say, 80% of the area median income and below,” Newhouse said.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Possible solutions

That’s the problem. But what’s to be done about it?

Newhouse and Hipple both agree that the issue is with the popular notion of housing abundance. Simply put, that philosophy holds that as long as you keep increasing the housing stock, the housing crisis will lessen. More supply, less demand. But, as the Georgetown study demonstrates, “you can’t just leave this to the market and think that’s going to meet people’s affordable housing needs,” Hipple said.

Fixing that requires leaning on the market so it produces every kind of housing, not just the housing that it’s most profitable to build. “We need all of the supply,” Newhouse said. “All of the supply.” And that means making it worth a builder’s while to build middle- and lower-income housing.

Arizona has already taken some steps in that direction. In 2024, the Arizona Legislature passed several bipartisan bills that preempted local zoning ordinances. One allowed for the construction of casitas, or accessory dwelling units, on lots zoned for single-family homes. Another allowed for multi-family housing — duplexes, triplexes and four-plexes — to be built in single-family-home neighborhoods. A third allowed for empty commercial buildings to be rezoned for adaptive reuse as apartment complexes.

Those bills have not been without controversy. Residents of Phoenix’s historic neighborhoods have railed against the middle-housing law before the Phoenix City Council, which could do nothing but shrug its shoulders and change its zoning rules to comply with state law. Whether those laws make a dent in the housing crisis remains to be seen, but Hipple called them a sign of forward progress.

“It’s definitely a step in the right direction,” she said. “With a crisis as severe as the housing shortage in communities across the United States, you’re going to have to take an everything-and-above approach.”

It’s likely not enough, though. Those zoning changes allow for middle-housing units to be built, but they stop short of incentivizing developers to build them. Newhouse feels that if cities and the state are serious about making housing affordable again, they could be doing much more.

For one thing, they could streamline the permitting process, which can throw wrenches in the gears of a housing development. Newhouse remembers touring a subsidized housing development built by Catholic Charities in Phoenix. “It took them 16 years to get it built” because of all the bureaucratic boxes they had to check, she said. “A lot of other developers would have walked away from the project.”

And a lot of developers won’t even start an affordable housing project unless it makes financial sense for them. That’s why Newhouse says the state also needs to put money where its mouth is. Congress expanded the Federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit last year as part of President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Arizona’s program, created in 2021, set aside $4 million a year to spend on affordable housing. One report found that the credit has resulted in the construction of at least 1,500 homes across the state.

But Arizona’s legislature declined to renew the program. At the end of 2025, it expired. That made Arizona the first state with a low-income housing tax credit to also ditch it.

Efforts are underway to bring the program back — Newhouse said she is “exhausted trying to renew that thing” — but it faces opposition from some Republicans. In particular, Arizona Senate President Warren Petersen said last year that he prefers tax cuts that help everyone — though, as Georgetown’s study shows, that won’t do much to increase affordable housing stock in Phoenix.

Clearly, more needs to be done, because whatever is being done already isn’t working. “We are short,” Newhouse said. “And we are short middle- and low-income housing across the board. It makes things really unaffordable.” So as you see all the new homes, townhouses and complexes you can’t afford, know you’re not crazy. Yes, the Valley is building housing.

It’s just not for you.