Billy Benjamin Hayes Jr., 39, is one of the state's most vocal marijuana activists.

Few people welcomed the Arizona Medical Marijuana Act when voters passed it in 2010 more than Hayes. The lanky father of three is a marijuana enthusiast, a grower for nearly his whole life who imbibes regularly, whether by smoking, vaporizing, or eating.

His name often is seen in Internet forums of the Arizona Department of Health Services, the agency that oversees the medical-marijuana program. Having learned just enough law to be dangerous during an eight-month stint in prison on a marijuana-possession violation, he's sued the federal government (unsuccessfully) over the law's "25-mile rule," which limits where patients can grow marijuana, and helps his pro bono pot-activist lawyer, Tom Dean, write court motions.

Hayes needs an attorney because he's also an entrepreneur who just may be ahead of his time. When Arizona Governor Jan Brewer and Attorney General Tom Horne sued the feds in 2011 in an attempt to derail the voter-approved state law -- and Brewer unilaterally thwarted voters' wishes to set up a state-authorized dispensary system -- Hayes helped open the first cannabis clubs that gave patients a safe alternative to back-alley drug deals.

The clubs gave Arizona its first storefront marijuana-sales operations about six months after voters passed the law. They were (and are, as several clubs still operate in the Valley despite the rise of legal dispensaries) among history-making changes in a state with harsh pot-prohibition laws.

The clubs pushed the envelope of what was allowed under the new law. Which suited Hayes' personality to a T.

Hayes co-founded the Arizona Cannabis Society with the Nutt brothers, Damon and Dana, days after the law was passed, later becoming its CEO. Hayes envisioned an advocacy and educational component to the organization. A Facebook page and website for the group were created in mid-November. Damon Nutt filed for corporate status with the state for the AzCS that May.

The state Department of Health Services, which oversees the medical-marijuana program, began accepting applications for medical-marijuana cards in mid-April 2011. A month later, about 2,500 residents had received cards -- yet they had no source for the medicine they could possess legally.

With several on-again, off-again partners over time, Hayes helped set up the Arizona Cannabis Club, which had three locations in the Phoenix area, like a franchise. The addresses were published in news articles and advertisements, seeming to dare police into a confrontation.

The Arizona Cannabis Society later opened a similar business, which it called a collective, or co-op, at 8376 North El Mirage Road. The storefront business, not approved by the DHS, offered patients buds and AzCS-made tincture that is said to reduce seizures in epileptic children. Another thing the AzCS and its state-registered patients and caregivers did in its strip-mall warehouse location is grow marijuana. A lot of it.

The businesses Hayes that helped run weren't the only unauthorized dispensaries to crop up in the state, but they certainly were among those with the highest profile. This wasn't a good thing for them, though, because the clubs fell into a legal gray area.

Under the new law, patients and caregivers could transfer marijuana to other patients or caregivers "if nothing of value [was] transferred in return." Staff at one of the clubs explained for a June 24, 2011 article in New Times that this could be interpreted to mean their businesses are legal, even without state authorization, as long as transactions were conducted only by people allowed to use and possess marijuana under state law. Like other clubs that opened around the state in 2011, clubs connected to the Arizona Cannabis Society received money (donations) from card-holding members, and one of the benefits of membership included marijuana.

At the same time, Hayes and his partners developed a business plan to transform the AzCS location in El Mirage into a state-authorized dispensary. They were, arguably, a tad too soon in the game. All they lacked was state certification.

Hayes is not just a pot enthusiast, he's a medical-marijuana patient. He has pain issues from various injuries and has been diagnosed with Crohn's Disease. His advocacy for marijuana knows few bounds.

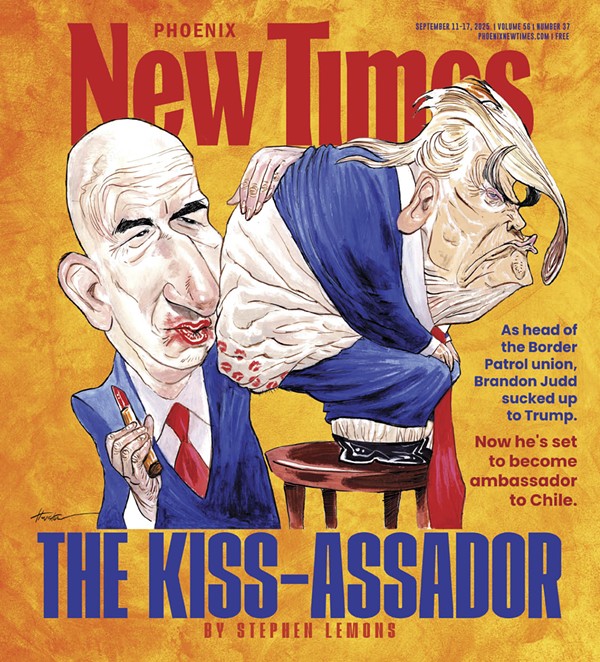

While many marijuana users avoid the limelight, keeping the pot part of their lives secret to avoid stigmatization, Hayes agreed happily to be photographed by New Times smoking weed in one of the clubs. A few months later, he invited New Times to the El Mirage co-op to shoot pictures for an online slideshow and a February 27, 2012 article that gave viewers an inside look at the cultivation and retail operation. (And that's Hayes taking a bong hit on the cover of this issue.) In retrospect, Hayes paid a predictable price for being in the spotlight.

A month after the slideshow was published, police raided the Arizona Cannabis Society, which had been open for about seven months.

Hayes' wife, Starr, 38, a hairdresser, had just left the house with one of the couple's two daughters, headed to preschool, when she was pulled over by police. She and the 2-year-old were taken to the El Mirage collective. They were made to stand beside the building; she's not sure why, because she never worked for the business. The raid involved an armored vehicle, a SWAT team, detectives in black ski masks, and a hazmat crew from the El Mirage Fire Department. Starr called her mother, who came to pick up the toddler.

"My daughter wasn't scared," Starr Hayes says. "She thought it was fun."

Police seized tens of thousands of dollars' worth of equipment and, they claim, 900 marijuana plants, which far exceeded the number allowed for any of the patient-employees. Cops slapped cuffs on Billy Hayes and interrogated him at the scene for about five hours. Starr Hayes was released and not charged.

Neither was her husband -- at first.

Coincidentally, Billy Hayes shares the name of the true-life protagonist in Midnight Express, the book and movie about an American sentenced in 1970 to a Turkish prison for smuggling hashish.

Like Turkey, Arizona has laws that call for severe penalties for marijuana users -- even as the plant is used by a significant percentage of the state's population and has gained widespread national acceptance. Reform could be coming soon: Last month, representatives of the Marijuana Policy Project of Arizona filed official paperwork launching a campaign for a 2016 legalization initiative.

For now, though, possession of any amount of marijuana is a low-level felony here. Hashish, shatter, hash oil, cannabutter, and other pot concentrates are considered (unscientifically) a separate "narcotic" under state law, meriting a stepped-up class-four felony designation.

For the 53,000-plus medical-marijuana patients in Arizona, possession of up to 2.5 ounces is legal. Patients also can purchase concentrated marijuana products like hash oil and shatter routinely in Arizona's 83 state-authorized dispensaries. Outside the protections of the 2010 law, though, posession and sale of cannabis becomes a felony.

A plea deal offered by the Maricopa County Attorney's Office, which is prosecuting Hayes for growing and selling marijuana products to card-holding patients, appears likely to put him in prison for longer than Turkey held Midnight Express' Billy Hayes. (That Hayes escaped in 1975 after serving five years of his life sentence, which Turkish officials may or may not have planned to commute.)

The deal would have allowed a judge to sentence Arizona's Hayes to between three and 12.5 years in prison. He also would have had to agree to a term of supervised probation when released or face an additional three to 12.5 years in behind bars.

He let the deal expire in late August.

The Nutt brothers, as well as several other El Mirage collective defendants, also were offered plea deals, though New Times isn't privy to the terms. The Nutts didn't return calls for comment.

They're probably busy running the Arizona Cannabis Society, which Hayes no longer is associated with.

The place reopened after the raid by El Mirage authorities and, in 2013, was granted a license by the state to operate as a legal dispensary.

In other words, Hayes' offense could be compared to selling liquor without a license. Except the penalties are far more serious than for an alcohol violation.

Arizona's severe punishments for cannabis offenders continue even as much of the nation moves toward outright legalization or significant decriminalization. The public and some of the nation's leaders now view marijuana prohibition with far more criticism than in the past. Advocates of legalization note that the expense of anti-marijuana enforcement -- and the harm that an arrest and criminal record can do to a young person's future -- don't jibe with the actual ills caused by use of the plant itself.

Despite all this, many Arizona leaders -- beholden to an arch-conservative voting majority -- have spoken out strongly in defense of maintaining the status quo.

County Attorney Bill Montgomery isn't satisfied with even this. He's tried to overturn the 2010 medical-cannabis law since it was enacted. He hopes a pending appeal of a lawsuit by his office against a Sun City dispensary results in eradication of the law. On October 30, in response to the Marijuana Policy Project's September filing with the state, he and two other Arizona county attorneys put out a news release calling for political and civic leaders to oppose lifting marijuana prohibition for adults.

That is, they want people like Hayes to go to prison, and they want the continued large-scale jailing of adult marijuana offenders in the state.

For his political activism as much as for his scofflaw attitude, Hayes and his family may pay a very high price.

Billy Hayes is headstrong and opinionated about marijuana.

He's an avid Facebooker who enjoys locating and posting videos of police wrongdoing. In interviews over the past few years, he's typically respectful ("Yessir" is one of his catchphrases), knowledgeable about his chosen profession, and nice.

In his extensive court history in Maricopa County, examples of his niceness and more break through all the talk of drug abuse. At 22, notes a 1998 pre-sentencing report on a pot-possession charge, Hayes was a single father of a 2-year-old whose mother lived in another state.

"Although he has not been ordered any child support, the defendant regularly sends money for the care of his daughter," the court official wrote. Hayes was a high school dropout but, the official continues, "reads at a level appropriate for his needs . . . Employed as a salesperson at Mills Mall, he has a number of job skills, including making jewelry and working as a tattoo artist."

The report was filed after Hayes was busted by Tempe bicycle-patrol officers scouting the parking lot of Main Street Billiards. Through binoculars, they watched as he pulled up in a pickup and parked. Finding him suspicious, they confronted him and found a baggie of pot and a pipe in his possession.

The bust wasn't Hayes' first.

Hayes grew up in Detroit and began using marijuana at age 12. Police questioned him several times about selling drugs, according to court records.

"He was shot at the age of 14, in a case of mistaken identity, and received multiple stab wounds on another occasion for what he claims was for some unknown reason," Michigan records state. "During his interview, he did admit a past history in another state, where he sold drugs to known gang members."

In 1994, at age 19, he was convicted of a felony in Detroit "for having a stolen vehicle and for larceny. He served 49 days in custody and was fined."

Hayes is reticent to talk about details in the report. Asked about that part of his Detroit past, he responds only that he never was busted there for selling drugs.

Hayes has, he admits, been highly interested in growing marijuana from a young age. His cultivation career began as a teenager after he spent a summer with a friend whose father was in prison on a marijuana offense. Agents had cut down all the plants on the man's rural Michigan property, but the boys found that much of it had grown back. The property's imprisoned owner also had a library on how to grow cannabis, and Hayes read every book.

He says he gave marijuana to sick patients.

"I never, ever sold weed," Hayes says. "I was always helping someone else grow . . . I'd get a cut of their grow. I would only help people."

His legal problems followed him when he moved to Tempe in the mid-1990s, setting off a chain reaction that continues to plague him.

In Maricopa County, most people busted with small amounts of marijuana are booked into jail and held for up to 24 hours, since any amount of pot is a felony in Arizona. The County Attorney's Office then makes its deferred-prosecution deal with first-time defendants, meaning no actual conviction.

Because of his past, Hayes wasn't offered deferred prosecution in 1998 on his pot-posession charge. He was found guilty of a felony and sentenced to three years' probation. A year later, a probation officer had to track him down for non-compliance. He was found at his fitness-center sales job. Upon his arrest for the probation violations, the officer found marijuana in his pocket. The discovery resulted in a new possession charge and an extension of his time on probation.

He was hauled before a judge in 2003, having failed numerous probation requirements. By then, he already had spent months in jail or halfway houses for missing his mandatory urine tests and classes. He'd tested positive for cocaine and marijuana earlier in 2003, records show, and had admitted ownership of cocaine found in his home.

Tired of living under rules he couldn't abide, Hayes refused probation and served eight months in prison, after which he was no longer under the thumb of authorities.

"If you look at it from my point of view, I would have [continued to fail] probation, because there's no way I would have quit smoking pot," he says of the period before he became a public pot advocate.

Prison was tougher than Hayes expected. He says he was beaten up by a member of a white gang. At the state's Lewis complex, he experienced a 15-day lockdown in 2004 during the country's longest prison-hostage standoff.

But he spent a lot of time in the prison's law library.

"That's when I realized that marijuana laws and other drug laws, inherently, are flawed," he says. "Because there is no victim."

Hayes' wife, whom he met in 2002 and married in 2006, used his savings to put herself through beauty school while awaiting his release. After he got out, she helped fund his education at an automobile trade school, which led to decent jobs installing equipment and doing fiberglass work on show cars.

Hayes is no stereotypically lazy pothead. Yet it cannot be denied that he has brought many of his problems on himself -- that is, he cannot blame his earlier legal woes on his activism.

As a deputy county attorney noted before his prison term began in 2003, Hayes was given "countless" opportunities to succeed on probation but "sabotages his positive efforts by reverting to behaviors that previously brought him before the court."

These days, Hayes is more defiant than ever.

Hayes needed something to do after the El Mirage raid in May 2011.

He was worried about the arrest and raid, but prosecutors didn't follow up with immediate charges. He felt compelled to continue his new life as public advocate for cannabis. And he pressed ahead with his burgeoning ideas for medical-marijuana businesses.

In late 2012, Hayes opened Cannabis Spot Vapor Lounge, at 4230 West Dunlap Avenue with a pot-for-donation scheme similar to the one that got the Arizona Cannabis Society and other clubs in trouble. Hayes explained to New Times at the time that his new business plan, involving a raffle-ticket system, was different enough to avoid the same problems.

Hayes was aiming for a Cheers for medical users, he says.

Arizona's 2010 law prohibits smoking medical marijuana in a public place, but Hayes saw a legal loophole in that the lounge was a private club accessible only to paying members. (Voters in 2006 excluded only indoor smoking statewide for tobacco products.) He boasted that he'd open 14 similar clubs across the state in the next two months.

Like a cannabis club, this potentially was a groundbreaking business idea: Hayes provided medical-marijuana patients a relaxing home away from home to use marijuana, complete with food, TV, music, and couches. Patients could rent smoking paraphernalia at the lounge, including equipment for "dabbing" with concentrates such as shatter. No alcohol was allowed.

Phoenix police raided the place on July 26, 2013, a week after a news broadcast about the lounge. A few days later, Hayes was charged with possession of marijuana and narcotics for sale (for the concentrates discovered), along with a count of illegal control of an enterprise.

Then, in April, the County Attorney's Office moved forward with a slew of charges against Hayes and other defendants in the 2012 El Mirage case. The charges include marijuana and narcotics for sale, illegal control of an enterprise, and misconduct with weapons (the latter an alleged violation of a state law that prohibits weapons in a place where pot is sold).

Montgomery's office, through spokesman Jerry Cobb, denied that charges were brought in the earlier El Mirage case as punishment for Hayes' opening Vapor Lounge. Montgomery says through Cobb that he's had no personal input in Hayes' cases.

What it all means is that Hayes is fighting multiple felony charges in two separate cases and doesn't seem likely to avoid prison.

But he is confident that he'll prevail in court and, in doing so, set a precedent for patient-to-patient sales under the medical-pot law. Indeed, he vows, he will sue Phoenix police for the return of his equipment and marijuana.

Kathy Inman is a pro-marijuana activist who formed the Phoenix chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws in 2008 and became director of Arizona NORML, which incorporated in 2012. She quit that job in August, she says, because of Billy Hayes.

Inman acknowledges that Hayes is a pioneer and "has done so much to be out front on this issue." She hasn't gotten to know Hayes as a friend, she says, but last year she and her husband came to his aid when others in the marijuana-advocacy community claimed he was a snitch for law enforcement.

"I defended him," she says. "I thought he was a good person."

Concerned about the reputation of one of the state's most visible pot activists, the NORML director invited Hayes to her Gilbert home several times. She says he showed her paperwork that essentially disproved rumors flying around him. They remained cordial until this summer, when Hayes began an online campaign against Inman because he believes she has a conflict of interest: Her son-in-law is Andrew Myers, one of the authors of the 2010 medical-marijuana law and executive director of the Arizona Dispensary Association.

Hayes long has opposed the virtual monopoly on growing and selling marijuana enjoyed by dispensaries under state law. On February 16, 2012, a month before the raid on his El Mirage collective, Hayes filed a 20-page complaint against the state in federal court. Acting as his own attorney, he argued that the state cannot prohibit patients from growing marijuana within 25 miles of a dispensary, as the law requires, because of the equal-protection clause in the U.S. Constitution's 14th Amendment.

U.S. District Court Judge Susan Bolton dismissed the case a couple of months later, noting that the complaint wasn't ripe because no dispensary yet existed within 25 miles of Hayes' El Mirage home. And because he had no right to grow marijuana in the first place, under federal law.

Hayes and six other plaintiffs have turned to county Superior Court in an attempt to eliminate the rule with a pending lawsuit filed in May.

With many eyes around the nation looking at Arizona as one of the states likely to have a legalization initiative on the ballot in 2016, Hayes wants to have a hand in writing the proposed measure -- and he doesn't appreciate the pro-dispensary influence of Myers and the dispensary industry. His arguments touch on some of the same issues in the national debate on marijuana laws, such as the best way to regulate use and sales of the plant. This month, for example, voters in the District of Columbia approved a law that makes growing and possession of marijuana legal for adults 21 and older, but the statute doesn't allow for Colorado-style retail shops.

Inman says she didn't know she and Hayes were at odds on any issue when he started railing against her to other marijuana supporters and in various online forums. Hayes was "relentless," she says.

She grew tired of accusations by Hayes and others that she was too supportive of dispensaries and the Marijuana Policy Project. Hayes "became the final straw," she says, so she quit her NORML post. She's continued her activism in other pro-cannabis groups.

"I try not to take it personally," she says of Hayes' campaign against her. "He's so nice. He's got wonderful kids. I like his wife . . . I don't want to see him go to jail, but when you play with fire, you might get burned."

Inman says she believes in staying within certain bounds but says Hayes "is willing to push the envelope every which way."

Ultimately, she thinks Hayes' recklessness is harmful to the legalization cause. She doesn't want to see prohibitionists like Bill Montgomery win, saying Hayes is good for the anti-legalization campaign.

Hayes, with other advocates in a group he leads called Registered Arizona Medical Marijuana Patients, continues to try to influence the drafting of the 2016 measure. He met with a national representative of the Marijuana Policy Project, he says, and lobbied to limit Andrew Myers' involvement in the drafting process "as much as possible." Hayes claims that Myers isn't trusted by some dispensary operators, as well as by some in the grassroots community.

Myers, who represents an industry that has publicly called on the authorities to close unauthorized clubs or other businesses acting as dispensaries, disputes this.

The Marijuana Policy Project, successful at passing the Arizona Medical Marijuana Act in 2010, is spearheading the legalization campaign. "The current drafting group," Myers says, "is the DPA [Drug Policy Alliance], the MPP, Lisa Hauser, Ryan Hurley, Gina Berman, the ACLU, and key in-state stakeholder groups and organizations, which will include representation from patient/consumer advocates. We don't plan on including black market operators [like Hayes] in the drafting process."

While Hayes' overriding strategy may prove ineffective, he continues to make his mark on Arizona's political scene concerning marijuana.

Tom Dean is optimistic that his client can beat the raft of serious charges against him.

Hayes has a public defender for the El Mirage case, Jason Rosell. Dean represents Hayes in the Vapor Lounge case, which has similar legal issues.

According to Dean, the charge of selling marijuana illegally shouldn't apply to cannabis clubs or collectives.

On one hand, the argument may be a legal longshot: The 2010 medical-pot law mandates a system of state-approved dispensaries in which the sale of marijuana to patients can be regulated tightly.

On the other, the law isn't that clear.

The statute states that cardholders can't be prosecuted "for offering or providing marijuana to a registered qualifying patient or a registered designated caregiver for the registered qualifying patient's medical use or to a registered nonprofit medical marijuana dispensary if nothing of value is transferred in return and the person giving the marijuana does not knowingly cause the recipient to possess more than the allowable amount of marijuana."

In a motion Dean crafted with Hayes, the attorney argues that the text of the law prohibits patients only from selling marijuana to dispensaries, not to other patients. The phrase "or to a . . . dispensary if nothing of value is transferred in return," he argues, is a wholly separate concept from the preceding text. Taking that view, he avers, patients or caregivers can provide marijuana to each other and accept something of value in return.

The argument has been made before but never settled. In 2011, Attorney General Tom Horne sued several cannabis clubs, including the Arizona Cannabis Society, claiming they violated the 2010 law by selling pot without a dispensary license. Lawyers for the clubs argued that patient-to-patient sales are legal. But the challenge never was tested: Following police raids on the same clubs, which cops say weren't coordinated with Horne's office, owners and managers of the clubs agreed to stop all transfers of marijuana, and Horne dropped the case.

Faced with the possibility of long prison sentences, some operators of cannabis clubs took plea deals that guaranteed probation.

It remains to be seen how Superior Court Judge Roland Steinle rules in Hayes' case. But on July 2, a Tucson patient accused of growing marijuana and selling it to other patients successfully used a motion based on the one that Dean and Hayes created.

Pima County Superior Court Judge Richard Fields dismissed the case, saying the 2010 law is vague and poorly written. The defendant shouldn't be prosecuted, he wrote, because it's possible that the exchange of something of value could be protected under the law. Under Arizona's "rule of lenity," a defendant, not prosecutors, get to win a criminal case when the law's unclear.

Kellie Johnson, chief criminal deputy for Pima County Attorney Barbara LaWall, says her office plans to appeal the ruling, which she acknowledges was significant.

Because of the complexity of Hayes' criminal cases, it'll take a few months before they're resolved. Montgomery's office, which may have an incentive to avoid taking the thorny patient-to-patient question before a jury, has yet to offer Hayes a plea deal that doesn't resemble something out of the National Geographic Channel show Locked Up Abroad.

Dean calls Hayes a "true activist in the best sense of the word. His patient-advocacy has demonstrated again and again his commitment to helping others . . . Losing Billy to prison would be a serious loss to the medical-marijuana community."

Dean says he and his client are ready to move forward with a trial if prosecutors don't offer a Hayes probation instead of prison.

Not that anyone could be assured Hayes will accept any plea deal or stick to probation. His latest creation, a Tempe "hash bar," demonstrates that he has no intention of giving in.

Unlike Vapor Lounge, Purple Haze House in Tempe doesn't provide a way for its patient-members to obtain marijuana, whether by raffle or other means. Its owners and Hayes, its manager, are confident this means there will be no problems with police and Bill Montgomery.

Open for about three months, the business at 31 West Baseline Road bills itself as a "medical spa" and hangout for medical-marijuana patients. The place makes money through membership fees, cover charges for live music or comedy shows, equipment rentals, and sales of snacks and drinks. Hayes has no direct role in the ownership this time. Purple Haze is owned by Michael Carlson, Andrew Young, and Sean Morley (a.k.a. professional wrestler Val Venis).

Hayes was hired as a consultant "to guarantee a success the first time around," says a Purple Haze news release. His "expertise was crucial in getting the business going without a snag."

At the November 14 official grand opening, Denver reggae band Coral Thief entertained about 50 patrons (the fire marshal's limit for the private club in a small strip mall next to a bar and laundromat). Murals and glowing neon grace the walls. At one counter, a "dabtender" assists patients taking huge hits of shatter from intricate dabbing rigs. The baked crowd, sitting on couches, stools, and at tables, was predictably mellow, chatting and laughing. While many of the members wore knit hats, sported dreadlocks, or showed other signs of cannabis culture, at least two patrons appeared to have physical disabilities.

On this night, the entrance fee of $25 covered not just the use of the club's bongs, but something to put in them. A local maker of shatter, Best Concentrates of Arizona, and a club member donated the product for others to smoke during the party.

One patron announced at the bar that he'd driven from Glendale for the celebration and liked what he saw. He'd taken two huge dab hits from a bong but seemed sober. A girl he came with, though, had a bad reaction to a dab and vomited in the parking lot, he said.

A few years ago, the partners and everyone at the grand opening could have been rounded up and charged with felonies, including the more serious narcotic felony because of the presence of hash-oil products like shatter. The hash bar is another sign that tolerance of marijuana here and elsewhere in the nation is growing -- despite the best efforts of prohibitionists like Montgomery.

Carlson says the business is prepared to expand rapidly. Hayes explains that one Tucson location will be near a dispensary and offer a kiosk for patients to obtain marijuana products. Starr Hayes, who says she doesn't know what she and their kids would do without Billy, says his involvement in the hash bar makes her uneasy. He tells her not to worry, but she says he told her not to worry about his past ventures, too. "I hate it," she says, sniffling. "I'm still proud -- very proud. But in the last few months, I've gotten a bit more not so positive. We've never seen any financial gains. We've been struggling the whole time."

The county attorney personally intervened this year in high-profile cases to offer deferred-prosecution deals to defendants accused of much more serious crimes than Hayes is accused of -- including felony child abuse. But it's unlikely that Bill Montgomery will give Hayes the same consideration.

Because the last thing prohibitionists want is to see Billy succeed.

Got a tip? Send it to: Ray Stern.

Follow Valley Fever on Twitter at @ValleyFeverPHX. Follow Ray Stern on Twitter at @RayStern.