Arizona legislators are framing their recent determination to impose a 12-month lifetime cap on welfare benefits and cut off assistance to some 1,600 families as a way to motivate the poor to take care of themselves.

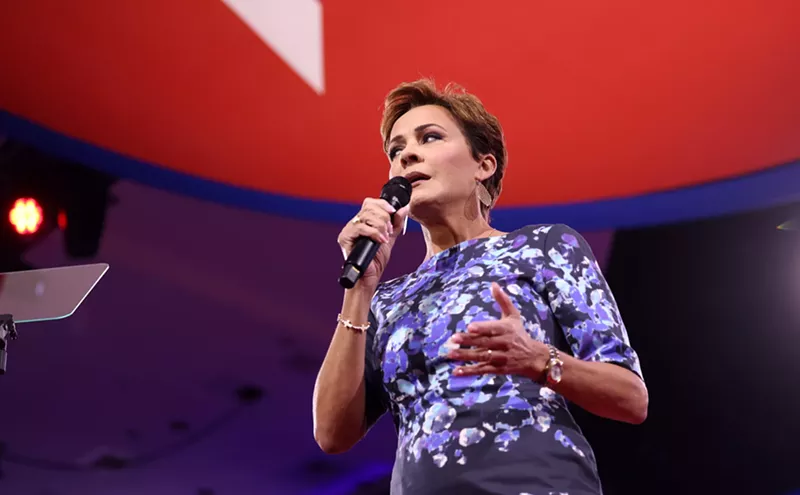

“I tell my kids all the time that the decisions we make have rewards or consequences, and if I don’t ever let them face those consequences, they can’t get back on the path to rewards,” Senator Kelli Ward, R-Lake Havasu City, said during the budget debate. “As a society, we are encouraging people at times to make poor decisions and then we reward them.”"We will continue to provide support to the neediest of families throughout our state, and we will encourage the able bodied to treat welfare like a safety net rather than a hammock." — State Senator Kelli Ward

tweet this

In a statement to New Times, she added that she believes the time limit — the shortest in the country — will push "the able-bodied to treat welfare like a safety net rather than a hammock.”

Impact studies conducted in other states that have already given such a time limit a try, however, suggest there’s no connection between getting kicked off welfare and landing a job.

After Maine imposed a 60-month lifetime limit for welfare recipients in 2012, for example, a researcher at the University of Maine concluded that revoking government aid did not lead to a statistically significant increase in wages or hours of employment.

A majority of welfare recipients already had some type of job when their assistance expired, social work professor Sandra Butler found, but were still living below the poverty line because they made an average wage of $9 per hour. Those who were not working, she found, faced significant barriers to employment, such as chronic illness, mental health issues, or substance abuse. More than 40 percent did not have a high school diploma.

When the families were cut off, nearly 70 percent were forced to turn to the food bank to feed their families, Butler reported. About 30 percent lost a utility service, such as electricity. Twenty percent were evicted from their homes, often landing in overcrowded living conditions or homeless shelters.

Similarly, a 2015 study of Washington’s time limit found that those who were booted off welfare made less money in the long term than those who gave up government assistance when they were ready. They were also more likely to be homeless years later. Twenty percent of families affected by the time limit did not have a home three years post welfare, compared to about 13 percent of those who left the program voluntarily after one year and 18 percent of those who left voluntarily after more than one year."For some people, five years isn't enough. Obviously, we're very concerned about limiting services to one year." — Liz Schott, welfare policy analyst

tweet this

“Many families don’t stay on welfare longer than 12 months or 24 months, but the families that do stay on longer are the ones with the greater barriers,” said Liz Schott, a welfare expert at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “We’re concerned that by cutting off the most vulnerable families, you’re putting them on a long-term path to worse outcomes for kids.”

Just increasing stress in the home can have lifelong consequences for children’s learning, behavior, and health, Schott said. Furthermore, in Washington, researchers found families that were dropped from the welfare rolls because of the state’s time limit were more likely to be investigated by child protective services after the fact than families that left of their own volition. Three years later, 17 percent were under investigation.

“For some people, five years isn’t enough,” Schott said. “Obviously, we’re very concerned about limiting services to one year.”

In Arizona, she said, the time limit is particularly problematic because the state spends very little money on services designed to help welfare recipients overcome substance abuse issues, treat mental illness, and transition into the work force.

In 2013, the state spent just 2 percent of its $230 million welfare budget on work-related activities and support, according to a Center of Budget and Policy Priorities analysis. The national average is 8 percent.

“Of course, it’s better for people to get off welfare,” Schott said. “But if that’s our goal, we should be investing in education, skills development, and support to help people get back on their feet. Not just pushing them out on the street.”