Illustration by Eric-John Torres

Audio By Carbonatix

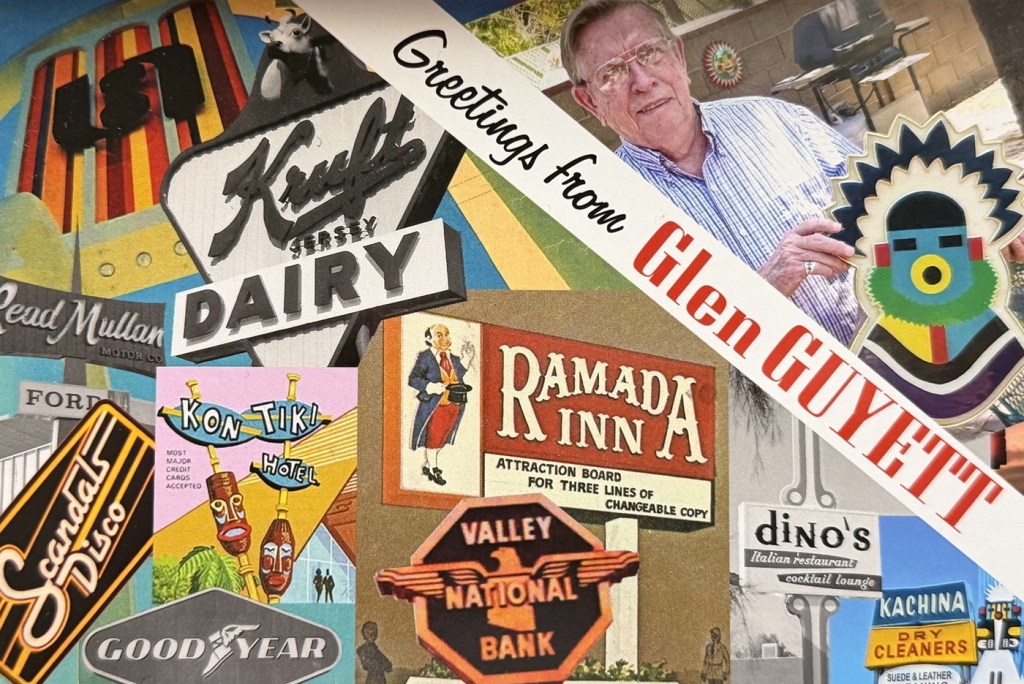

Glen Guyett spent decades lighting up the Valley.

Over 40 years, the prolific artist and designer created some of Phoenix’s most iconic signs. They rose above streets and highways and became beloved local landmarks. Many remain etched in the memories of longtime Valley residents, even if the signs themselves have long since vanished.

Guyett died on Jan. 5 at his home in Mesa from prostate cancer. He was 97.

Guyett’s work was unique, kitschy, memorable and often larger than life. From the 1950s onward, he designed dozens of towering, neon-drenched signs across the Valley. Bill Johnson’s Big Apple along Van Buren Street. My Florist on McDowell Road. Tempe nightclub JD’s. Famed motor lodges like the Kon Tiki Hotel and Mesa’s Buckhorn Baths.

Benjamin Leatherman

Most were products of their moment. Born of midcentury Phoenix, they boasted modern lines, playful themes and plenty of glowing neon built for drivers in motion. Each beckoned Valley residents and visitors, and helped to define a growing city’s identity.

Alison King, a Phoenix historian and midcentury modern guru, says Guyett’s work unapologetically embraced its era.

“How would I describe his work? Joyful. Entertaining. Unabashed. Monumental,” King says. “He really liked to make a statement, and many of his works are so magnificent.”

Only a handful of Guyett’s creations remain today, including the jester-adorned sign at now-defunct Grand Avenue nightclub Mr. Lucky’s and the Shamrock Farms display along Interstate 17.

Arizona historian Marshall Shore says Guyett’s signs are unmistakable landmarks that became the stuff of local lore for Valley lifers.

“When you drive around the city, it’s hard to miss signs that he’s created,” Shore says. “If you drive by and haven’t lived here long, you won’t know they’re a Glen Guyett sign. They’re testaments to old-school Phoenix and another time in the city’s history.”

Local designer Jim Bolek says Guyett’s influence went far beyond just dreaming up signage.

“Without really realizing it at the time, Glen was what we’d now call an environmental graphic designer,” Bolek says. “He wasn’t just making signs. He was creating places, landmarks that shaped how people experienced the city.”

Guyett’s work helped create a sense of place at a time when Phoenix was figuring out what, exactly, it wanted to be.

“His work is public work,” she says. “Just like public art, it has exposure to anybody riding through that part of town. Because it’s so monumental and easy to see from the

street, it helps us position ourselves in the Valley and know where we are.”

Benjamin Leatherman

From KCMO to PHX

Guyett’s flair for art and design took shape long before he came to Arizona. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1928, his paintings won numerous art contests while he packed his high school schedule with math classes, fueled by dreams of becoming an architect.

“He really loved math and was great at it,” Joyce Guyett, one of his five daughters, says.

Following a stint studying drafting at an engineering school, Guyett enrolled at the Kansas City Art Institute on a two-year scholarship he won after his paintings were exhibited at Pittsburgh’s Andrew Carnegie Institute.

In 1946, Guyett began designing commercial signs, first in Kansas City and later relocating to Arizona. He moved to Phoenix in 1951 with his wife, Doris, to escape the cold weather. One of his first

gigs was working for the Electrical Advertising Agency, where his creations included a 12-by-13-foot map of Arizona in 1954 inside the state legislature.

Mesa Historical Museum

Guyett eventually landed at Myers & Leiber Sign Company, where he spent the next 14 years. He became the company’s art director, designing and creating works that became unmistakable Phoenix landmarks.

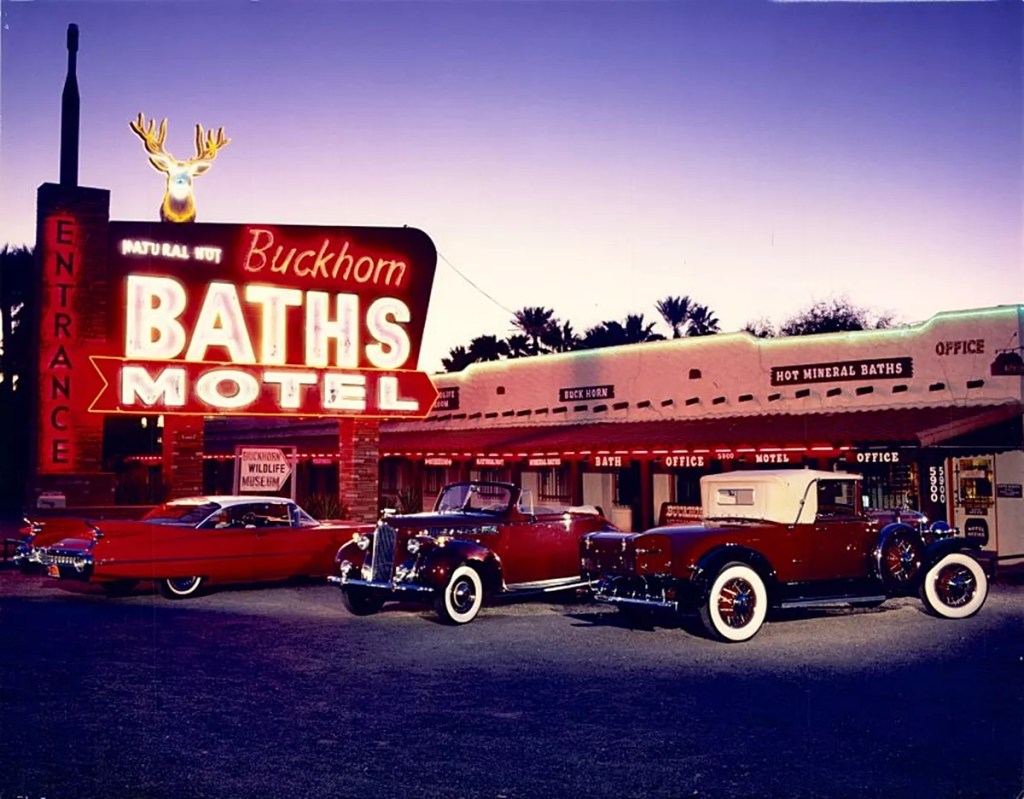

One of his earliest projects there was updating Mesa’s Buckhorn Baths Motel during an early ’50s remodel. In addition to designing the motel’s iconic neon sign, Guyett left his mark inside the property.

“He wasn’t just doing their sign,” Shore says. “He also helped install cabinets and painted scenes on the walls of the lobby.”

Petley Studios

Built for the road

Neon signage surged in the 1950s alongside the rise of car culture. Guyett designed scores of neon signs for Valley businesses, particularly along major thoroughfares like Van Buren Street, where businesses clamored to be noticed.

“Neon was a hot-ticket item at that point,” Shore says. “There were so many companies that were doing signs in those days and people pretty much realized you had to have an eye-catching neon sign to thrive.”

Speaking to King’s website, Modern Phoenix, in 2011, Joyce Guyett recalled the precision and inspiration her father brought to every project. “Ideas would be drafted by Glen in the form of a drawing or model to scale and painted to look exactly like the finished product,” she said then. “Everyone loved these creations and they closed many deals. Glen then created the final design and did the math that made the sign sound for wind and stress factors. His influence on Van Buren signage was to bring the newest sign technology to a small Western town with innovative modern ideals.”

A few miles north along Camelback Road, Courtesy Chevrolet’s iconic sign is another local midcentury landmark that Shore claims Guyett helped create. The towering, arrow-shaped display debuted in the mid-1950s, pairing a Googie-leaning form with shimmering twinkle lights.

While a Courtesy Chevrolet spokesperson credits the design to Millie Fitzgerald, wife of dealership co-founder Ed Fitzgerald, Shore says Guyett’s fingerprints are likely there based on the technology involved.

Susan Arreola Postcards/Phoenix Public Library

“There’s always been debate about whether he was involved with the Courtesy Chevrolet sign,” Shore says. “The thing about Glen’s signs is, if it has twinkle lights, it was something he helped dream up. That was a skill he brought with him from Kansas City.”

Other attention-grabbing Guyett signs were born in that era.

In 1956, Guyett designed a monolithic sign for Bill Johnson’s Big Apple along Van Buren Street, topped with a longhorn bull’s head that was impossible to miss. Two years later, he revamped the octagonal logo of the now-defunct Valley National Bank, giving a glow-up to an eagle he once joked “looked like a sick chicken.”

The redesign became a 35-foot-tall porcelain sign installed atop downtown Phoenix’s Professional Building. Powered by a one-horsepower motor, it was the world’s largest revolving sign at the time and loomed over the city’s skyline for more than a decade. It also graced the cover of advertising trade publication Signs of the Times and even briefly appeared in the opening sequence of “Psycho.”

.

Mr. Lucky’s famous sign

In the 1960s, Guyett’s work continued to get noticed. His soaring sign for the now-defunct Tempe nightclub JD’s won an award from General Electric. It set the stage for an even more iconic nightlife creation.

In 1966, Phoenix businessmen Bob Sikora and George Xericos tapped Guyett to create a lively, jester-inspired sign for their glitzy, Vegas-style nightclub Mr. Lucky’s on Grand Avenue north of Indian School Road.

“Vegas was really going back then, so there was talk at the Arizona Capitol about making Phoenix into another Vegas,” Joyce says. “They wanted some of that Vegas money, because people were passing through on the way there.”

The Mr. Lucky’s sign became one of Guyett’s best-known works. It still turns heads today, even after falling into disrepair following the nightclub’s closure in 2008.

“It’s one of the most prominent signs in the Valley. It sticks out. People who drive down Grand remember it and ask, ‘Where’s that sign?’” Shore says. “We’re still lucky to

have that one, no pun intended.”

Marshall Shore

‘Phoenix history that will probably never be replicated’

Many of Guyett’s signs were built to be big and bold, a product of their time and the looser rules that governed midcentury Phoenix. They were built for a city on the go,

designed to be impossible to ignore.

That kind of scale no longer exists. Shore says modern signage laws in the Valley make Guyett’s work a relic of a different era, impossible to replace.

“We have different signage codes now, so that’s why some of those signs have never come down,” Shore says. “If they were brought down to be repaired or something, they can’t put them back up. They’re gone forever.”

Over the decades, most of Guyett’s signs have disappeared as businesses closed and the Valley developed. To Alison King, that impermanence is exactly what gives Guyett’s work its cultural weight.

“It represents a very specific slice of Phoenix history that will probably never be replicated again,” King says. “It’s part of what makes these signs so precious and rare,

so let’s keep them around for as long as we can. Since they’re not in excess right now, I don’t think it’s fair to call it visual pollution. I see them as cultural artifacts.”

Marshall Shore

‘He was a great dad’

As much as he’s remembered for his signs, Guyett’s work extended beyond those creations. He designed logos, branding and other items for now-defunct businesses like Tang’s Imports and Arizona Bank in the 1970s and for the then-Ramada-owned Renaissance Hotel chain in the 1980s. “He did really intricate little stuff and not just signs,” Joyce says.

Guyett’s creativity also played a role in his home life. He often found time to paint in his spare time, Joyce recalls, including creating murals of Disney princesses on the walls of his daughters’ bedrooms. Later, when Joyce performed in local rock and pop bands, he designed their business cards and logos.

“Whatever we needed, he would create for us,” Joyce says. “He was a great dad.”

Guyett retired in 1991 and went on to teach art and painting classes. Late in life, his work found a new audience as an influx of Valley residents discovered Phoenix’s midcentury past. In 2019, he was inducted into the Arizona Sign Association’s Hall of Fame.

Bolek says Guyett’s work still stands out, though not because of its scale.

“As you drive around town, you’ll still see some of the stuff Glen has created and it still looks fresh and modern,” Bolek says. “It’s distinctive and it didn’t feel trendy.”

Joyce says her father was always amazed by the affection his work has gotten. All the while, he remained humble.

“He was always fascinated that people were fascinated with his signs,” she says.