Heard Museum

Audio By Carbonatix

In Indigenous Maidu culture, the figure of Coyote is a trickster and shapeshifter who embodies the full spectrum of human experience. Both a creator and destroyer, playful and profound, Coyote is a figure of adaptability and survival.

Artist Harry Fonseca, who was born in Sacramento, California, in 1946 and is of Nisenan Maidu, Hawaiian and Portuguese heritage, was deeply influenced by learning about Coyote in his own Indigenous culture.

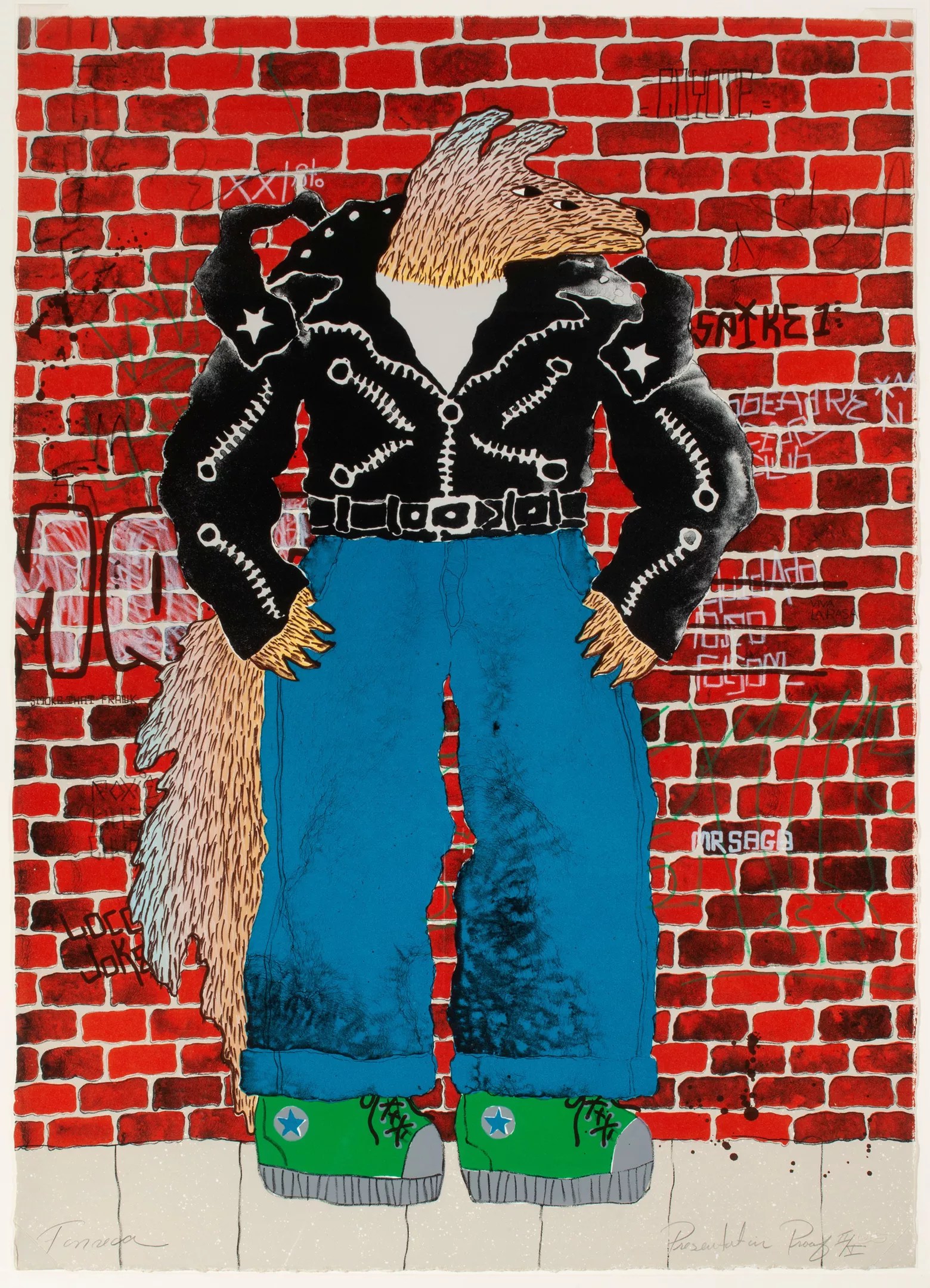

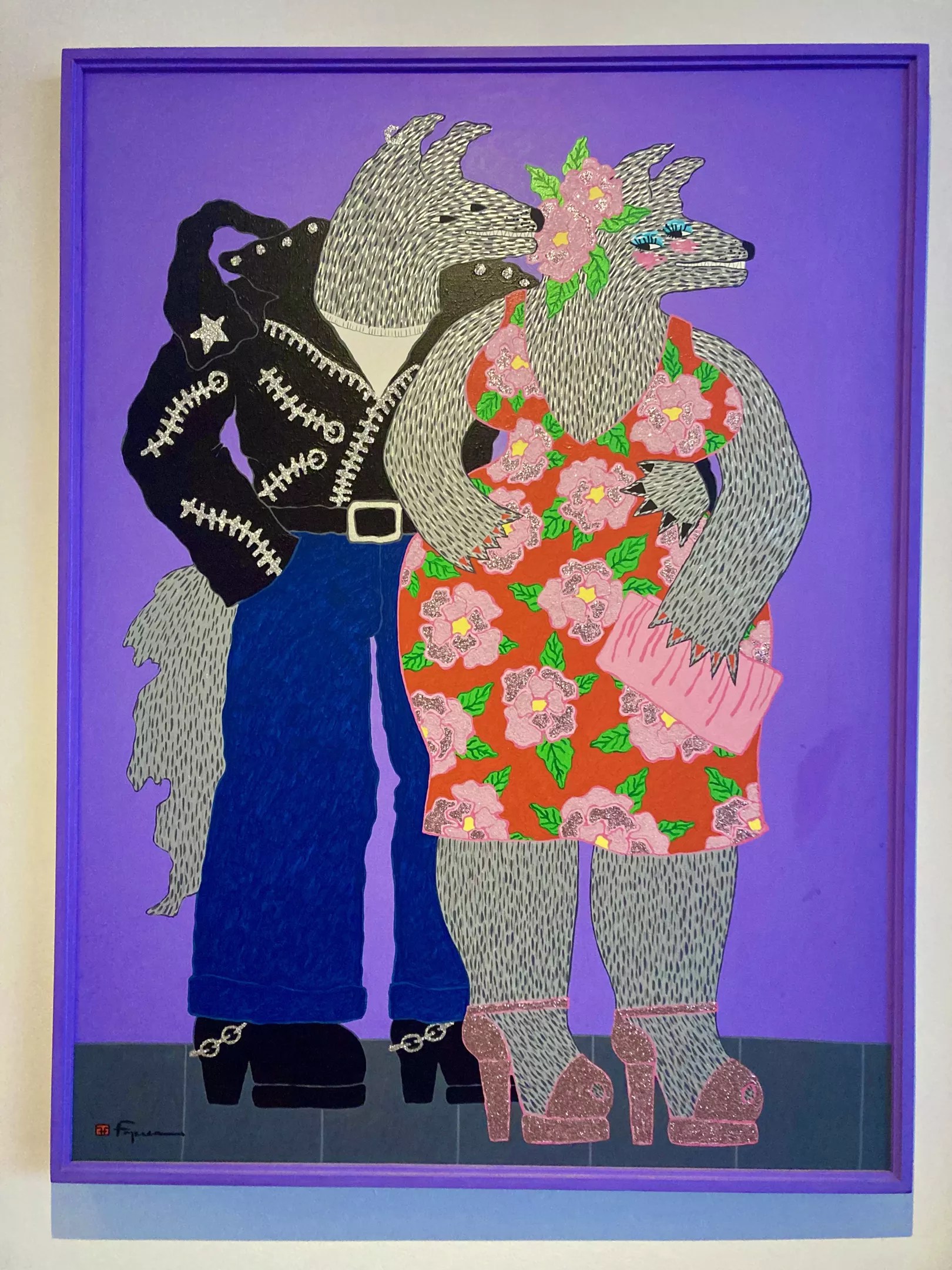

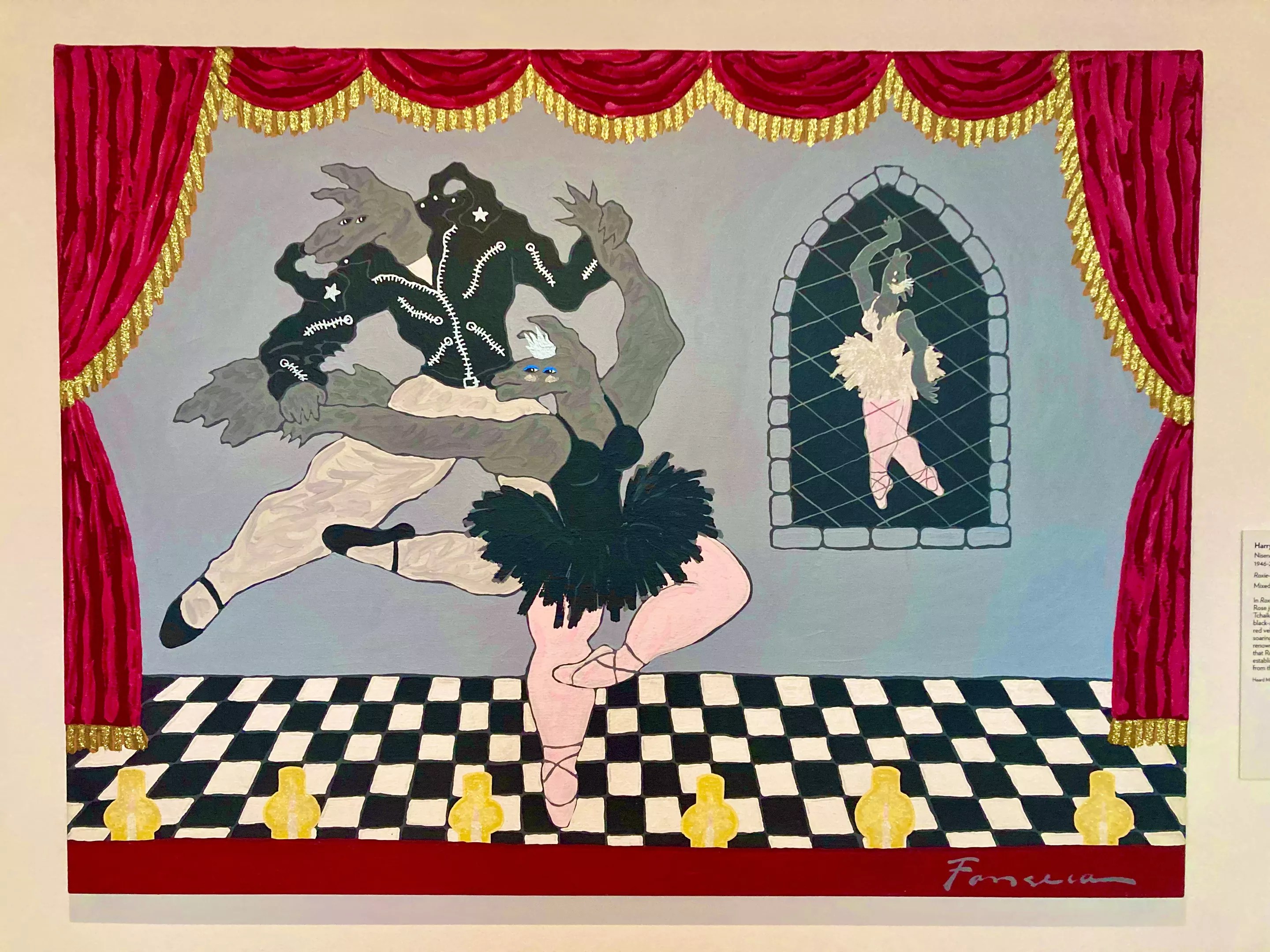

“Harry Fonseca: Transformations,” now up at the Heard Museum, is the first exhibition dedicated to exploring Fonseca’s expressions of “queerness” through the reintroduction of his Coyote character. A vibrant blend of Maidu culture and the explosive San Francisco scene of the 1970s and ’80s, Fonseca’s colorful and bold artworks feature Coyote in leather and black Converse sneakers, dancing in a scene from “Swan Lake” and cuddled with another Coyote figure in a queer-coded embrace. Coyote is able to change gender, dress and attitude to traverse multiple landscapes and cultures.

Fonseca himself explored the fluidity of his own identity through his art practice. Throughout his nearly 20-year career as an artist, he was a staunch supporter of queer communities and causes including AIDS and HIV prevention. With his death in 2006, Fonseca left a creative legacy that is both mysterious and familiar. For people on the queer or genderfluid spectrum, there is an undeniable recognition of self in the character of Coyote.

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

Fonseca’s work invites viewers to embrace the multiple identities within themselves and others. In an interview during his lifetime, Fonseca once said, “That’s what I understand about my coyotes. They are yin-yang, black-white, negative-positive. After a while, there’s no separation; the shades of gray come. My coyotes are always gray. I have tried to make them brown, but they come out gray. Actually, coyotes are many colors, usually like a tattered old coat. Coyote is a hard figure to pinpoint. He’s in flux constantly.”

Phoenix New Times spoke with Heard Museum curator Roshii Montaño about discovering Fonseca’s artwork, and personal effects, how Fonseca’s Indigenous culture and the legends of Coyote inspired decades of his art and life, influence of the queer hippie and Pop Art movements of San Francisco, and the beauty, joy and resilience in remaining undefinable.

“Harry Fonseca: Transformations” will be on view at the Heard Museum through April 19, 2026.

“Rose and Coyote Dressed Up for the Heard Show” by Harry Fonseca.

Royal Young

Phoenix New Times: Let’s talk about Harry Fonseca’s life and how he came to his Coyote practice in his art.

Roshii Montaño: 1972 was pivotal for Fonseca and his introduction to a really important figure and knowledge keeper in his life, Henry Azbill. He was Maidu and also had Native Hawaiian lineage, like Fonseca, so he was introduced to him through the community. He learned basket practices from him, and most significantly, he fostered an understanding of the Coyote dance during that period. This gave Fonseca an understanding of Coyote, an introduction to performance and movement.

If you have that understanding of that ceremonial Coyote dance, it’s the foundation for so much more knowledge. Fonseca really saw the Coyote figure, especially in Maidu, as someone who is a trickster, but also really important in conveying all these different aspects of human identity, and just being human.

The Maidu can be kind of raunchy and explicit with some of their understandings of Coyote – that’s just what it is. Sexuality and gender in Indigenous cultures and communities, I don’t want to speak too broadly, but it’s very documented that Indigenous people didn’t stray away from that. It wasn’t until colonization that we were very limited and ideas of Christianity were implemented. But before then, sexuality and gender were just out there.

And seen as just a part of the natural world, not seen with a sense of morality or shame. It was more like, are you a good person in your community? That’s what really matters.

Yes, and I would say specific figures in the community, which I guess in our modern language we would call transgender (or Two Spirit), they were sacred figures. I’m Navajo, and I know they were sacred in our communities.

To get into some of the historical context, these paintings were being made in the 1970s in San Francisco, and very much in the counterculture hippie movement of the time. How did those influences get blended in Fonseca’s work with Maidu knowledge and upbringing?

For this exhibition specifically, I did a lot of research in our own archives, because we have a few boxes of Harry Fonseca’s personal correspondence and pamphlets he kept from things that were significant to him. He grew up in Northern California; he stayed there for a majority of his life because he wanted to be close to Maidu lands, culture and community. But he also spent time in the Mission District in San Francisco. His own way of living his life was complicated – he was married to a woman and they had a child but he was also exploring these facets of his identity.

Thinking about that period in San Francisco, he was very supportive of organizations at the time led by Native people, and very supportive of organizations doing AIDS and HIV prevention. So he would allow these organizations to use his depictions of Coyote on their pamphlets. He was not necessarily out at that period of time, but he still supported these people because they were his friends and community.

So there’s that aspect, but there’s also so much queer coding in Fonseca’s artwork, like showing Coyote in the Mission District dressed up in leather. I think those two things, the location of Coyote and Coyote’s dress, seemed like such a connection to the luscious queer community of that time.

“Roxie The Black Swan” by Harry Fonseca.

Royal Young

Going back to Two Spirit people, my feeling is that term really corresponds to a modern gender nonconforming identity. So we understand that there’s not a need to be defined, we don’t need these boxes.

Yes, and when I was doing this research, I found it really hard to use specific identity labels. Because Fonseca is no longer with us, I would talk to his friends, and the language was such a non-issue at that time. He didn’t want to or need to be defined. In my exhibition text, I wrote that his community just knew him as “Harry.”

I think Coyote as a character, as a figure, really highlights that. Coyote is just Coyote.

I see that as a way of distancing oneself from identity proclamation, but also a way of owning it. So it’s not tricking, but there is that sense of “now you see me, now you don’t.”

Absolutely. I use the term kaleidoscopic identity, because one of his friends used that in conversation and I felt that was so important in Indigenous identity, too. The general public view of Native people at that time – there’s so much flexibility and transformation that can happen through the paintings, and I think there’s a lot of power in that.

I want to talk about the mask that reveals the truth. This idea in art all over the world that through performance, or presenting a fiction or character, we can reveal something deeply true about the world or society.

In Maidu, Coyote is really a figure that teaches about humanity, not just its positive aspects but also its negative aspects and the full spectrum of humanity. Fonseca depicts Coyote as an aesthetic strategy to traverse multiple landscapes. For example, Fonseca puts Coyote in this beautiful ballet scene of “Swan Lake.” So that’s an example of indigeneity blossoming in this space because there are no limits to where indigeneity can exist. We exist everywhere.

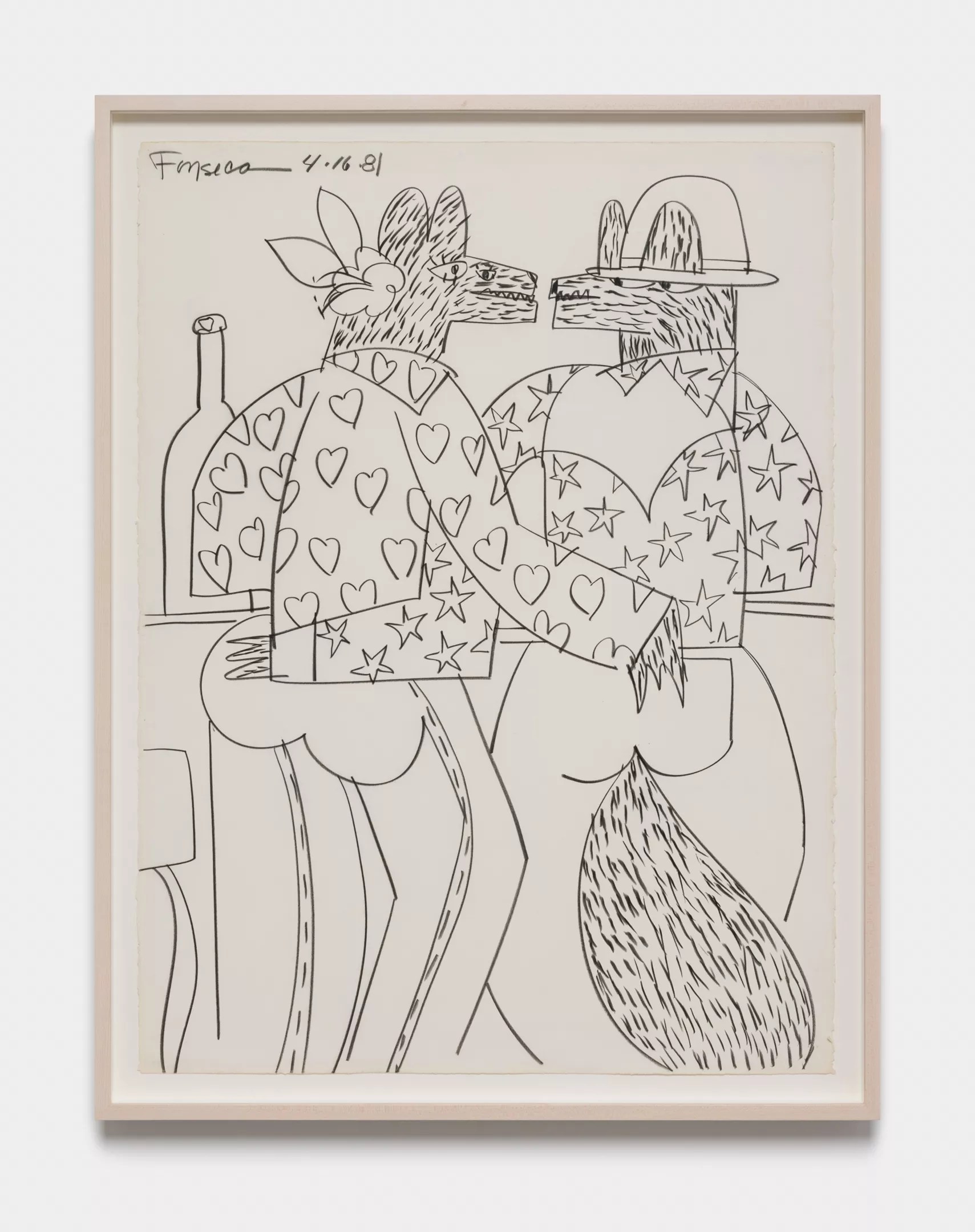

“Pow Wow Club” by Harry Fonseca.

Heard Museum

On a personal note, one of the reasons I resonate with the artwork so much is, my dad was an artist. He passed away four years ago, was married to my mom for over 30 years. He was also what I call a non-disclosing queer man; he never really defined. So I’m fascinated by the personal narratives and how they weave through the work.

One of the things people always ask me on tours is, “Is Fonseca Coyote?” and I don’t think he always is. There’s an in-between where he can express himself genuinely through this character, but that doesn’t mean he is the character. It’s just an expression and understanding of these identities and how they are constantly shifting. I also think they are a way of surviving – of surviving the times, of surviving the Native art world and the more conservative aspects of his upbringing. He had to exist in all those spaces, and I think Coyote helped him navigate all that.

We’re still living in a world where so many violent systems are in place. So many of those limits of who we can be as people are still in place. So what is it about Fonseca’s art today and his Coyote figure that can invite us to see and celebrate the multitudes in ourselves?

There is beautiful queer Indigenous joy and resilience in Fonseca’s work. The first time I saw his work was when I started at the Heard Museum – I had no idea. Before that, I went to school at Stanford, I went to the Folsom Street Fair, I hung out in the Mission. When I saw his work for the first time, it was like I saw my Indigenous queer kin. There was something I responded to, that drew me to it, that I recognized.

During Fonseca’s life, as someone who was concealing a lot of his identity, and as a Native, he gathered so many Native artists and a community who loved and supported him. So there was this deep aspect of kinship there. There is consistent affirmation of joy in his work, and also refusal to give in. If we retain joy and beauty through our practice, we can find ourselves, and we can remain resilient.