Jimmy Magahern

Audio By Carbonatix

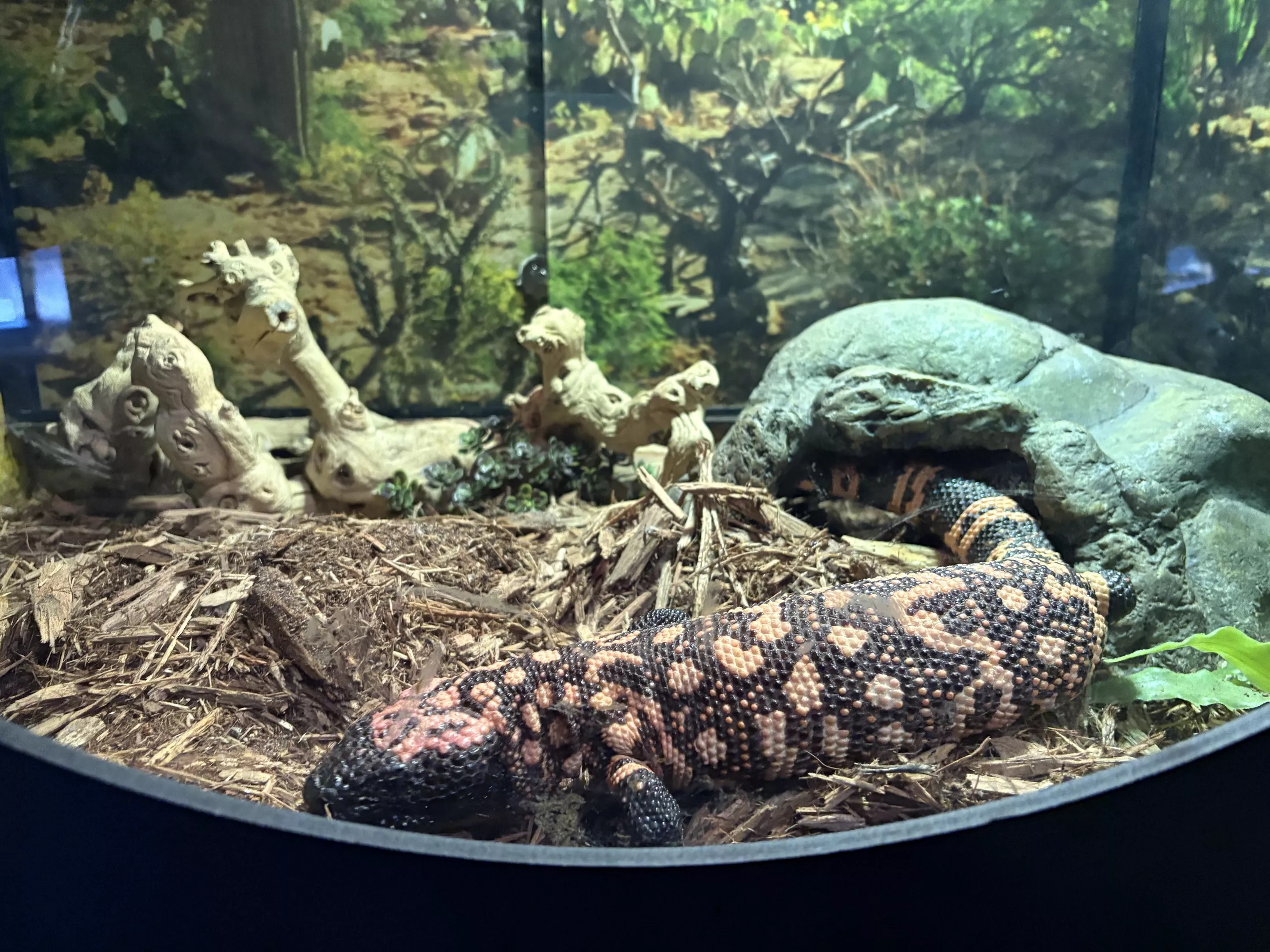

Just before visitors leave “The Power of Poison,” a traveling exhibition from the American Museum of Natural History on view at the Arizona Science Center through Aug. 24, Zoë, a Gila monster on loan from the Phoenix Herpetological Society, approaches the glass dome on her enclosure and peers out at the group of children staring at her excitedly.

“She loves a camera,” says Kristina Celik, the center’s marketing director, unlike the golden poison dart frog in the lush Colombian Chocó forest walkthrough area at the exhibit’s entrance, who tends to hide in his moist enclosure.

“Fun fact,” Celik says. “When Gila monsters bite, they have venom, much like a snake. But instead of just injecting the venom through a bite, she saws her teeth into you. To remove a Gila monster, you need a crowbar – her jaw is so strong. And the venom is so painful, it’s that level-10 pain.”

But there’s a bright side. “The venom that she injects into you contains exendin-4, a peptide that’s similar to GLP-1, which drugs like Ozempic mimic. So a bite from her could be a natural way to lower your blood sugar,” jokes Celik, “if you don’t mind the horrendous pain.”

Phoenix, make your New Year’s Resolution Count!

We’re $11,000 away from reaching our $30,000 year-end fundraising goal. Your support could be what pushes us over the top. If our work has kept you informed, helped you understand a complex issue, or better connected you to your community, please consider making a contribution today.

Zoë, after all, is in the Poison for Good section of the exhibit, which underscores its central irony: Sometimes poisons can heal, or lead to scientific breakthroughs.

It’s a theme that seems particularly relevant right now, with vaccine-skeptic appointments in the nation’s HHS department and CDC questioning scientific consensus, dismantling health safety nets and pushing unvetted alternatives. Could RFK Jr. soon endorse Gila monster bites as an effective weight-loss treatment?

One display depicts Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor, who reportedly took mercury-based elixirs, believing they would grant him immortality.

Jimmy Magahern

Elsewhere in the exhibit, the Villains & Victims Gallery explores famous historical poisonings, like Napoleon’s and Cleopatra’s. And the Poison in Myth & Legend area features looming dioramas of the witches of “Macbeth,” brewing their potions with poisonous plants; Snow White sleeping off her bite of the poisoned apple; the “Alice in Wonderland” Mad Hatter (whose madness, the exhibit suggests, may have come from the mercury poisoning in the felting of hats back in Lewis Carroll’s time); and real-life figure Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor, who reportedly took mercury-based elixirs, believing they would grant him immortality. Instead, they likely hastened his death.

That one brings to mind the obsessions of tech billionaires like Peter Thiel, Bryan Johnson and Sam Altman, who have invested heavily in experimental life-extension technologies in their quests for immortality. Thiel, for one, has been looking into things such as heterochronic parabiosis, the biochemical joining of the circulatory systems of older and younger organisms. Silicon Valley startups like Ambrosia have tried to commercialize plasma transfusions from young donors to reinvigorate older people – at $8,000 a pop.

“The Power of Poison” delves into the science of toxins.

Jimmy Magahern

While these modern pursuits are (generally) grounded in emerging science, they still flirt with the same hubris, fear of death and access-based experimentation as the ancient attempts “The Power of Poison” pokes fun at.

“Isaac Newton died eating mercury because he believed that it would make him immortal – and he was, like, one of the smartest people of his time!” says Darrah Johnson, a former middle school teacher who’s part of the center’s Blue Crew that leads the live interactive show within the exhibit. “And there’s another part of this exhibit about people who thought a really great cure for your morning sickness was arsenic.”

She sees “The Power of Poison” as “a little dark,” but actually offering a “reassuring” perspective in an era when scientific authority is often challenged.

“We’ve always been bad at healing each other,” Johnson observes. “Just because people are advocating for things that are maybe not super scientific now, that doesn’t mean we’re going to stop pursuing science and truth.”

Ashe Gibson, staff scientist at the Arizona Science Center who worked closely with the American Museum of Natural History to add engaging activities to go along with the exhibit, agrees that the show offers a reminder that bad ideas and blind spots in medicine are nothing new, and that progress generally emerges through ongoing curiosity and correction.

“Not that long ago, we didn’t even have the capacity to test for poisons,” says Gibson. “In the 1800s, it was a brand-new science. It shows us that just remaining curious and knowing that new discoveries are always going to come with more research is how we got from there to here.”

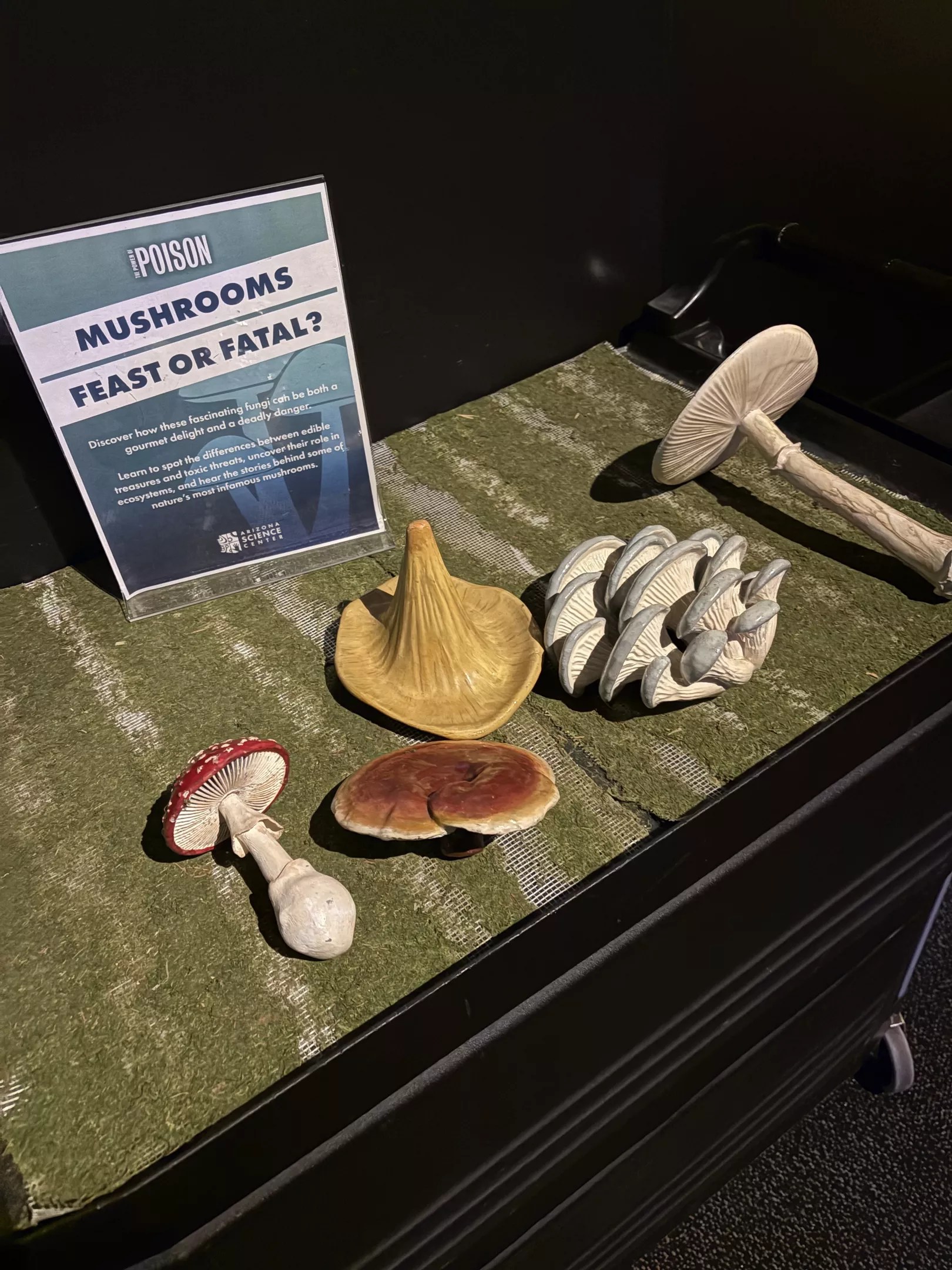

One section of the exhibit is devoted to mushrooms.

Jimmy Magahern

To that end, Gibson even created a homegrown addition to the touring exhibit titled Mushrooms, Feast or Fatal? It highlights the dangers and the potential of mushrooms – from their toxic varieties to their emerging roles in mycoremediation (the use of fungi to clean up environmental pollutants), and alternative medicine (psilocybin-containing species being studied in clinical trials for treating depression, PTSD and addiction). Using 3-D printers and paint, Gibson and their team hand-crafted lifelike mushroom models in the Science Center’s CREATE makerspace, next door to the main building.

“That one was my brainchild,” Gibson says. “I love the science of mushrooms and mycology. But it is a more taboo topic. It’s something that’s up-and-coming with so much new research.”

Gibson says the exhibit’s poison dart frog – that shy-but-deadly golden hopper that entices visitors into the ersatz Chocó forest – is a living example of nature’s biochemical paradoxes.

“We’ve known for a while that these frogs are toxic, but we didn’t know how, exactly,” Gibson says. “Only in 2024 did research start identifying what proteins specifically in their digestive tract are allowing them to synthesize that toxin and move it into their skin so they can secrete it.”

Zoë, a Gila monster on loan from the Phoenix Herpetological Society, is part of the exhibit.

Jimmy Magahern

Who knows? Maybe one day we will find a way to harness Gila monster venom – without the saw bites – to slim the human body.

“It’s a great reminder that science is always changing,” says Gibson. “We’re always gaining new discoveries that help us get a better understanding of the world around us.”

The Power of Poison is on view at Arizona Science Center now through Aug. 24. Tickets and schedule info at azscience.org.