Celestis

Audio By Carbonatix

When longtime Scottsdale resident Philip Chapman was a young boy in Australia, he used to look up at the night sky.

World War II was ravaging the globe.

Chapman watched as 1 million of his countrymen left home to fight against the Axis powers, and at times, the stars were his only escape from the misery of global conflict.

Amid the tumult, he only wanted one thing: to “get off this little rock” and go to outer space, where no one could hurt him, family members recall.

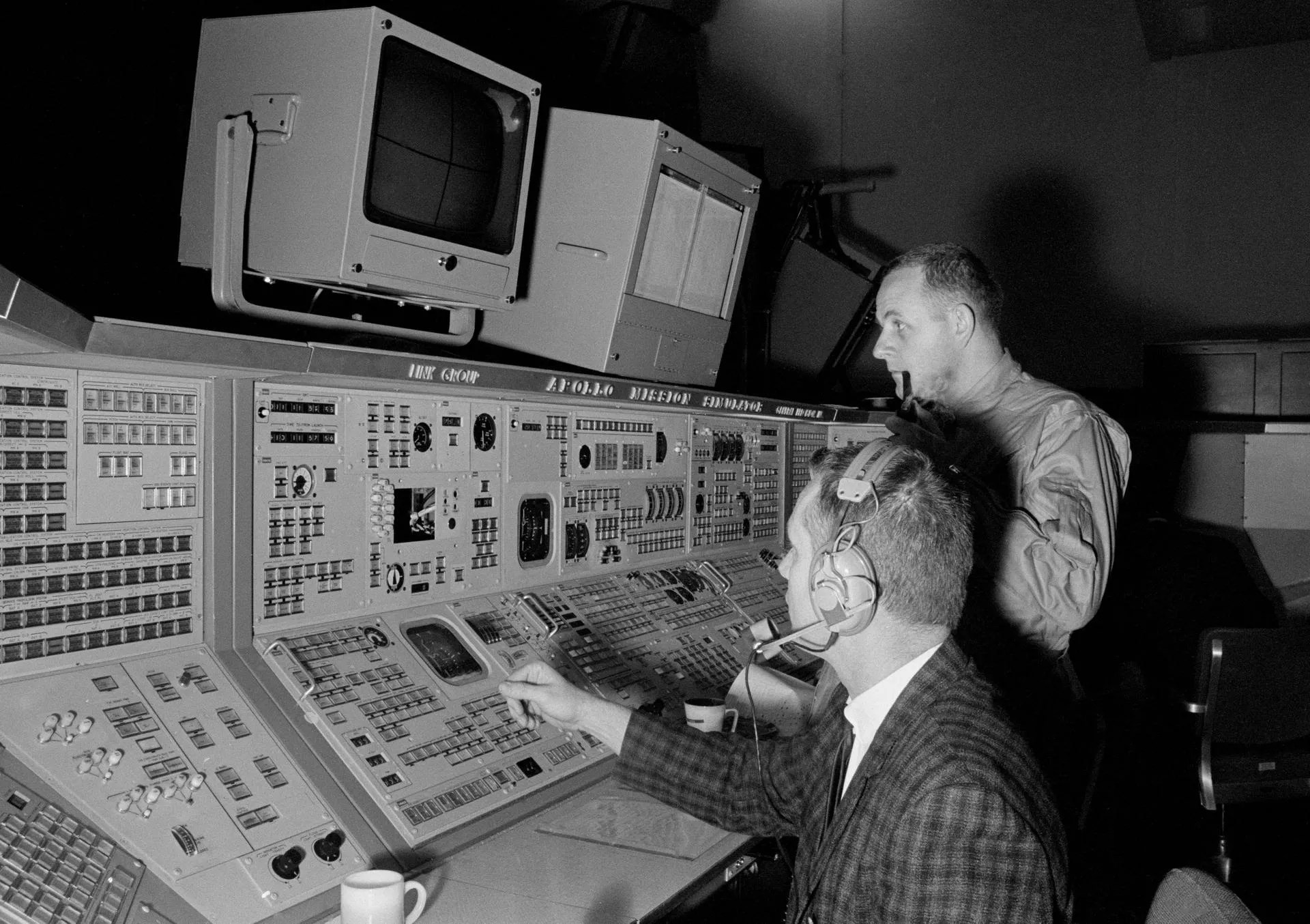

The young Chapman went on to become a scientist-astronaut for NASA, embarking on fantastic adventures to Antarctica and being heavily involved in the 1971 Apollo 14 mission to the moon. In 1967, he became the first Australian-American astronaut after joining the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Experimental Astronomy Lab.

“We can build arks for societies of humans to go on multigenerational missions,” he once said as a young man, according to NASA.

Despite his devotion to advancing humanity and space exploration, he was robbed of his only chance to explore the cosmos firsthand as a planned Skylab mission fell through when the funding dried up.

That loss was pivotal for Chapman. He quit NASA over the introduction of the space shuttle program to work in the private aerospace sector and settled in Scottsdale, where he lived out the rest of his life.

He never got to fly in space.

Last year, he died unexpectedly at age 86.

Philip Chapman was the first Australian-born NASA astronaut in history.

Celestis

But Chapman’s story isn’t over, thanks to Celestis, Inc., a Houston-based company that launches cremated human remains into space. Space burial awaits.

Soon, he will posthumously fulfill his nearly century-old dream of traversing the solar system.

His final resting place will be the final frontier. No one has done it before.

“It is not a sad funeral,” Chapman’s wife, Maria Tseng, told Phoenix New Times on Wednesday morning. “It will be three days of celebration.”

Chapman will first board the Aurora Flight, named in honor of the ionized particles that color the night sky in polar regions with eerie light. The flight is scheduled for liftoff on November 30 from Spaceport America in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico.

It will mark the 19th memorial space flight launch since Celestis began in 1994.

“It fits Phil’s goals and life motivations very well,” Tseng said.

Before Richard Branson, Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos, Chapman took a special interest in commercializing space travel. He took to heart NASA’s one-time mission statement, later co-opted by Musk’s SpaceX: “Make humanity a space-faring civilization.”

As a mission scientist for Apollo, Chapman performed all the research and testing that precluded the mission.

Celestis

“He was ahead of his time,” Celestis CEO Charles Chafer told New Times.

On the Aurora Flight, Chapman’s remains will board a SpaceLoft XL rocket ship and reach outer space, about 120 miles from Earth’s surface, and briefly encounter the effect of space’s weightlessness before returning safely to the ground. The flown capsule, containing his cremated remains and DNA sample still sealed inside, will be presented to family and other loved ones after the flight.

“The best part about this mission is after his journey he gets to come back to me,” Tseng said.

The reunion will be short-lived, though. In December, Chapman is going back to space.

This time, he’s going to make history. And he won’t be coming back. He will be somewhere in deep space, beyond the far side of the moon, where he will settle into a nearby orbit around the sun.

Chapman will be flown on the Enterprise Flight during a permanent deep space mission as part of a payload fight tasked with delivering a rover to the moon. That’s to avoid wasting rocket fuel, a concern often broached in SpaceX’s plans to pioneer tourism in space.

The vessel will contain mementos from Chapman’s time in the Apollo program, including his astronaut helmet, ashes, DNA, and messages of well-wishes from loved ones and fans all over the world engraved on radiation-proof metal chips.

The intense cosmic rays in deep space will not blemish the words of loved ones for lifetimes.

“To me, that is very meaningful,” Tseng said. “He will orbit the sun for as long as the sun lives.”

Chapman’s vessel will become “the first human outpost in space,” Chafer said.

Loved ones observe a space burial.

Celestis

“It’s an unbelievable honor that Maria and her sons sought us out and wanted to honor Phil in this matter,” Chafer said. “He is an amazingly accomplished person who never made it to space, so in that sense, we’re thrilled to be able to provide his first and second flights into space. He had a critical role in getting us to the moon and back in the Apollo program.”

As a member of a backup crew and a mission scientist for Apollo 14, Chapman performed all the research and testing that precluded the mission. He also worked to solve the mysteries of how the universe works and the pressing question of whether there’s life on other planets or in other galaxies, according to NASA.

Celestis flew the ashes of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry earlier this year and actor James Doohan, who played Scotty, into space in November 2014. It also flew the ashes of Eugene Shoemaker, the famous geologist who figured out that the Meteor Crater – also known as the Barringer Crater – near Flagstaff, is an asteroid strike.

Philip Chapman’s astronaut helmet is among the Apollo 14 mission mementos to accompany his remains in a deep-space casket.

Celestis

Shoemaker trained the Apollo astronauts in northern Arizona, where Chapman became his friend, and they developed a mutual admiration for each other. Shoemaker’s ashes are the only human remains on the moon, flown there by Celestis.

It’s not just space exploration enthusiasts who are memorialized with funerals beyond Earth’s atmosphere, though. Celestis has flown restaurant workers, truck drivers, and mountain climbers from 35 countries.

A deep space memorial for Chapman cost a little under $10,000, according to Tseng.

“The commonality is simply a yearning to go to space,” Chafer said. “It’s stepping out on a starry night and wanting to join the cosmos.”

But for Chapman, it was more than a want. It was a drive. And it was almost a reality.

During his tenure at NASA, Chapman was slated for Skylab B’s mission to space, but it was officially canceled in May 1973.

Skylab B, a part of the Apollo program, was a proposed second American space station that was planned to be launched by NASA, but was nixed due to lack of funding.

Chapman “was very, very, extremely alarmed” when the mission was called off, Tseng recalled.

He predicted Skylab B would go down in history as a stepping stone in humanity’s migration to other planets.

“It signaled a change in NASA’s position from being a leading space exploration agency to something much more reduced,” Tseng said.

In a 1970 letter to the scientific community, scrawled on a yellowing leaf of paper with United States Government letterhead, Chapman begged to salvage the only chance he ever had to realize his childhood dream of reaching the stars.

Family members provided the letter, which preserves Chapman’s dejection and desperation, to New Times.

“We have very few friends left, in the scientific community, in Congress, or amongst the general public,” Chapman wrote.

But he held out hope: “It is surely clear by now that the Titanic manned space program is not as unsinkable as it may have seemed … I, for one, have a dumb faith that man is in space to stay.”

His protestations were futile. But he was never one to give up, those close to him remember.

Chapman even suggested to his colleagues, in jest, that they should create a fake alien artifact and give it to Neil Armstrong to “find” on the moon, to spark renewed interest in the missions there.

When all else failed, Chapman resigned from his NASA post in 1972.

He steered his post-NASA career to support the Strategic Defense Initiative, commercialize the Solar Power Satellite, and help startups in the emergent private sector commercial space industry. His mission involved joining forces with a private research firm to develop laser propulsion and solar-panel satellites with Peter Glaser, who invented them.

“His love for space was limitless,” Tseng said.

She recounted meeting her late husband in 1979 at a professional dinner and asking him about the twin paradox, a theory that people traveling at the speed of light age slower than people staying on Earth. The phenomenon was addressed accurately in the 2014 film Interstellar, which included contributions from Nobel laureate Kip Thorne.

As a scientist-astronaut for NASA, Philip Chapman helped lead the 1971 Apollo 14 mission to the moon.

Celestis

“I said, ‘Tell me about time travel and space,'” Tseng remembered saying to Chapman. “He thought it was wonderful. The rest is history.”

Chapman was an outdoorsman with a penchant for hiking and exploring. He wintered in Antarctica for the experience of living in a forbidding place, in preparation for his expected trip to space that never came to be.

He and other Apollo astronauts visited geologic sites in Arizona, sparking Chapman’s love for the state, in the 1960s. Ryan Anderson, a planetary scientist and developer at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center, said that the Grand Canyon and other sites in the Flagstaff area were even better classrooms for astronauts headed to the moon.

Arizona contains a number of exposed canyons and existing craters, like Sunset Crater just north of Flagstaff, where NASA field-tested rovers, spacesuits, and other equipment.

Chapman loved taking risks, and he loved blazing new trails. Evidently, even after shuffling off this mortal coil.

“Everyone agreed this would be the most remarkable way to commemorate Phil,” Tseng said. “It’s much better than any regular funeral.”

Longtime colleagues would sum up Chapman’s life and posthumous interplanetary ambitions in one quote from French essayist Stéphane Audeguy: “What we call ‘death’ is merely a transition between different kinds of matter.”