Arizona Supreme Court

Audio By Carbonatix

“Hello, I’m Daniel,” a young man wearing a blue suit says to the camera.

His lips move, but those movements don’t quite match the robotic-sounding words coming out of his mouth. He stands in front of U.S. and Arizona flags and a TV with the Arizona Supreme Court’s seal, but the edges of his head and suit are fuzzy, as if he’s using a preset Zoom background. The closer you look, the less normal he appears.

“Daniel” is an artificial intelligence avatar, created in March by the Arizona Supreme Court. In the last five months, “Daniel” and his female-coded counterpart, “Victoria,” have provided short rundowns of often esoteric judicial opinions in a concise, easy-to-understand – if often uncanny – manner. They are the brainchildren (if not the actual children) of Chief Justice Ann Timmer, who aims to make Arizona’s sometimes confusing court system more accessible and understandable to the average person.

Earlier this month, though, viewers of a recent “Daniel” were more creeped out than educated. In an Aug. 5 video posted to YouTube, the AI avatar, with its shapeshifting facial hair and overexaggerated blinks, announced that the court had denied an appeal from death row inmate Jasper Phillip Rushing, upholding his conviction and nudging him one step closer to a state-sanctioned killing.

Rushing was initially sentenced to 28 years in jail after the 2001 murder of his stepfather. In 2010, he murdered and mutilated his cellmate, Shannon Palmer, in the Lewis Prison Complex in Buckeye. In 2015, a Maricopa County jury found Rushing guilty of Palmer’s murder and sentenced him to death. The Arizona Supreme Court vacated his death sentence in 2017 after the trial court failed to tell jurors he was ineligible for parole. A second trial jury also sentenced him to death, leading to Rushing’s second appeal to the state Supreme Court, which, as “Daniel” explained, was denied.

Many found the “Daniel” video announcing Rushing’s case off-putting. The organization Death Penalty Alternatives for Arizona compared the video to a “Black Mirror” episode in an Instagram post. Social media users responding to the post felt similarly. A user named Brian Schubert called the video “disgusting” and described the avatar as a “glorified cartoon.” “Yuck,” wrote a user named Holly. “And it’s smiling? Wtf.” On Bluesky, the video was described as “fucking gross,” “horrifying” and a signpost of “dystopian hell.”

In an interview with Phoenix New Times, DPAA survivor advocacy coordinator Destiny Garcia criticized the “bureaucratic and cold” video as “a blatant form of dehumanization.” Survivors of violence “don’t want justice delivered by an algorithm,” she said, adding that if an informational video is necessary, actual people should deliver this type of news.

Rushing represented himself in his latest appeal. Two attorneys from the Maricopa County Public Defender’s Office, who advised him, did not respond to a request for comment.

Reached by New Times, Timmer called the criticism “fair,’ adding that “it’s good to get feedback on these things.” However, “Daniel” and “Victoria” aren’t likely to go away. They will probably explain future death penalty rulings, although Timmer said trigger warnings or new avatars may be introduced to convey sensitive decisions.

“I’m gratified to hear the criticism,” Timmer said. “It kind of opens those conversations here to think, ‘OK, how should we do this? What’s the best way to go forward?'”

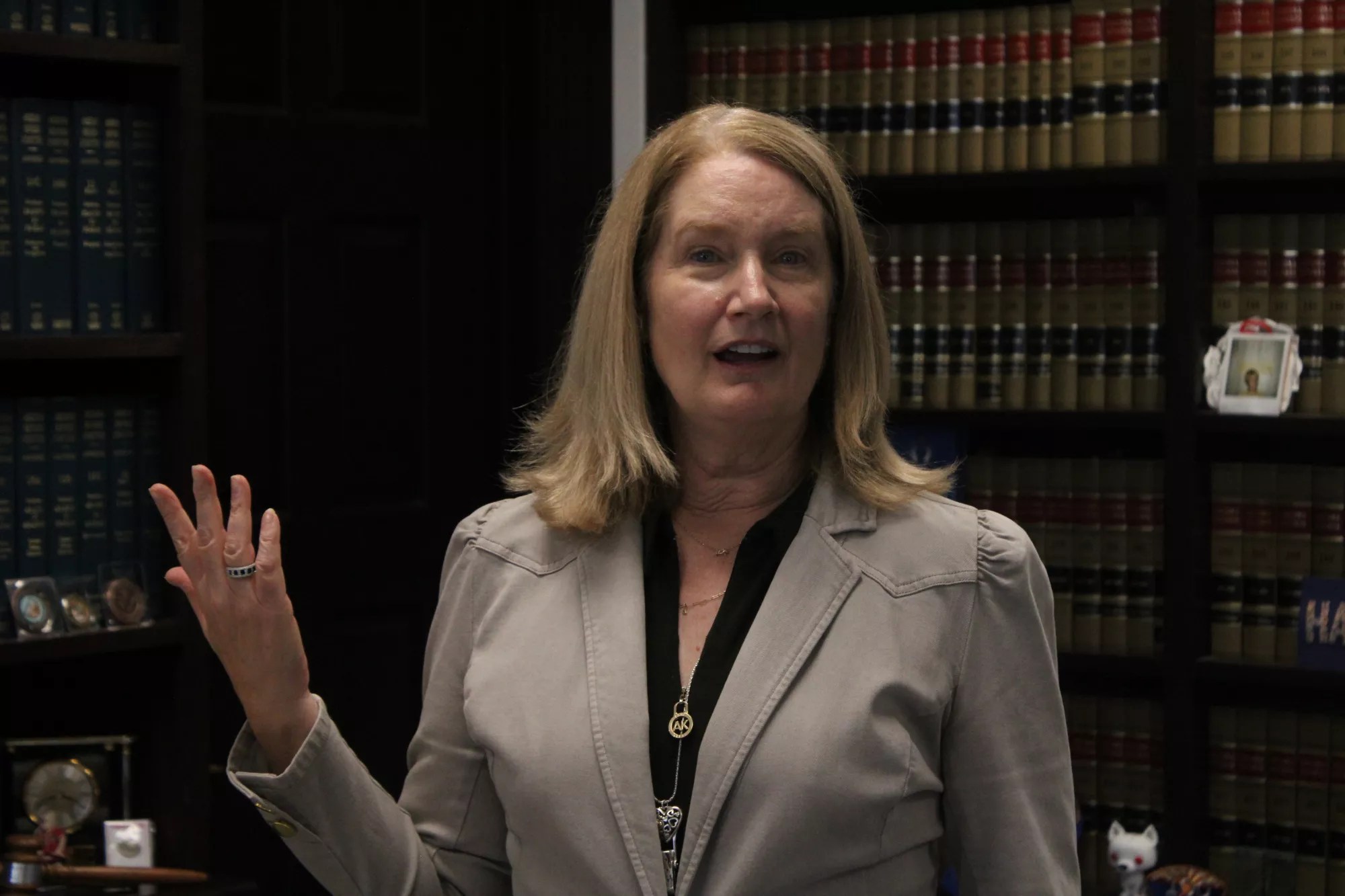

Ann Scott Timmer, the chief justice of the Arizona Supreme Court, said the court’s AI “reporters” are intended to help make judicial rulings more accessible.

Morgan Fischer

Why AI court reporters?

The AI “court reporters” are the product of Timmer’s “… and Justice for All” agenda for the judicial branch, which aims to expand and promote access to justice. Under Timmer’s leadership, the court wants to “remove barriers that impede access to justice” to make the state’s justice system more “open and accessible,” according to the strategic agenda.

Timmer and the court’s communications director, Alberto Rodriguez – who is an actual person – brainstormed the idea of AI-generated reports in early March. Due to many people watching their news on their phones or through short video clips, Timmer has “always wanted video” of judicial opinions being read, preferably at an eighth-grade reading level.

“I’ve got kids,” Timmer told New Times in an interview earlier this summer. “This is how they get their news.”

The AI avatars have read decisions about customers tripping over signs in Circle K, property owners clearing liens on their homes, families collecting restitution after their child was murdered, schools not being responsible for off-campus injuries and more. The decision in Rushing’s death penalty case was the first to generate notable backlash.

At first, Timmer was “envisioning a real person” in the videos, but thought using an actual justice might be “kind of unseemly” and would take a long time. That’s when Rodriguez suggested using fully licensed and customizable – and “culturally ambiguous” – AI avatars created by the company Creatify AI. The rest of the justices were on board, Timmer said, and by the second week of March, the avatars were up and ready to be used for the next opinion.

“It looks so real,” Timmer said. “Unless you watch it for a little bit and you realize, ‘OK, it’s not a real person.”

The scripts that “Daniel” and “Victoria” read are written by the justices who authored each opinion. Each justice has their own ChatGPT license, and Timmer uses the AI chatbot to help her create a script. She prompts ChatGPT with the opinion and tells it, “This is intended for public consumption. Can you give this to me in an eighth-grade reading level?” Once ChatGPT spits out a script, Timmer will “make a tweak or two,” smooth out the language and then send it to the other justices, who may make more tweaks before approving it. Then, Rodriguez will put the script into Creatify, which will create the image for the court’s YouTube account.

“It’s fun,” Timmer said. “It’s our voice in better-looking people.”

Since the first video was posted on March 12, Arizona’s conservative seven-justice court has decided that all of its decisions, no matter the content, will be announced through these AI-generated videos, alongside the actual opinion and a press release. Each opinion announcement – including cases that involve child molestation, people being horrifically injured, the termination of parental rights and more – is treated the same “in terms of delivery of the information,” Timmer said. The court aims to have the AI reporters have the same matter-of-fact demeanor on every case so that they can “give it as neutral a recitation as possible,” she said.

The script is straightforward, which often means the avatars are emotionless when discussing these “very weighty issues,” which Timmer admitted can be “jarring.” And while the court tries to be “sensitive” and never “gleeful,” Timmer said, it’s not the court’s “place to show that kind of emotion.”

Timmer wants to continue improving and updating the court’s AI news reporters. For death penalty cases, Timmer has toyed with the idea of including a trigger warning before a video that contained a death penalty matter – though the videos don’t include graphic or specific details about the underlying cases – or using older, more serious-looking avatars.

Despite the criticism from DPAA, Timmer said the project has received “overwhelmingly” positive reactions, giving Timmer the impression that more people know about the court’s work. That viewership is relative, it seems. On the court’s YouTube channel, the number of views each video receives varies drastically – some have more than 2,000 while others have just 85. The average video received more than 400 views.

The court has no plans to shelve the AI reporters.

“It has had the impact that I wanted,” Timmer said.