Morgan Fischer

Audio By Carbonatix

A mother seeking to keep her kids away from her soon-to-be ex-husband, who led police on a high-speed chase with their children in the car. A grandmother who is facing eviction after she stopped paying rent because her landlord refused to fix her broken air conditioning. A veteran who was kicked off Medicaid after an online scammer stole his identity.

All of these people have one thing in common: They need a lawyer, but they can’t afford one. To navigate Arizona’s complicated legal system – to gain full custody of their kids, to stay in their home, to restore access to their health insurance – they will turn to one of three Arizona nonprofits that provide legal aid.

Every year, a small army of attorneys, caseworkers and volunteers helps roughly 24,000 low-income Arizonans steer through a crisis. They provide legal representation in eviction cases, help domestic violence victims obtain protection orders and assist the victims of countless scams. Basically, when something goes wrong and you don’t have the money for an attorney, Arizona’s civil legal aid system is there to help.

That safety net is hardly as robust as it should be. Arizona’s three civil legal aid groups – Community Legal Services, DNA People’s Legal Services and Southern Arizona Legal Aid – can accept only about 50% of the cases they receive. But it catches a lot of people at risk of falling through the cracks.

“It’s scary to imagine a world where we don’t have the ability to provide those services,” said Pam Bridge, the director of litigation and advocacy for CLS.

That scary world may be around the corner.

As he has with so many programs that help people, President Donald Trump aims to end the federal program that funds much of the operation of Arizona’s civil legal aid services. In late May, the Trump administration released its 2026 fiscal year budget proposal, which slashed the federal Legal Services Corporation budget from $560 million to $21 million in order to administer an “orderly close out.” LSC, which is a nonprofit established by Congress in 1974, was also a target of Trump’s in his first term, though he wasn’t able to shutter it then. This time, though, he may succeed.

If he does, Arizona will be particularly ill-prepared. LSC allocates roughly $16.5 million to Arizona’s three legal aid groups each year, making up the vast majority of their funding. Losing federal funds could effectively end the services that thousands of residents rely upon every year. Arizona is one of three states that spend no state money on civil legal aid. On average, a state civil legal aid system gets 19% of its funding from the federal government, but in Arizona, that number is 80%.

“We are largely dependent, almost entirely dependent, on federal funding to protect Arizonans’ rights,” said Chris Groninger, the chief strategy officer of the Arizona Bar Foundation, which provides a small portion of civil legal aid funding.

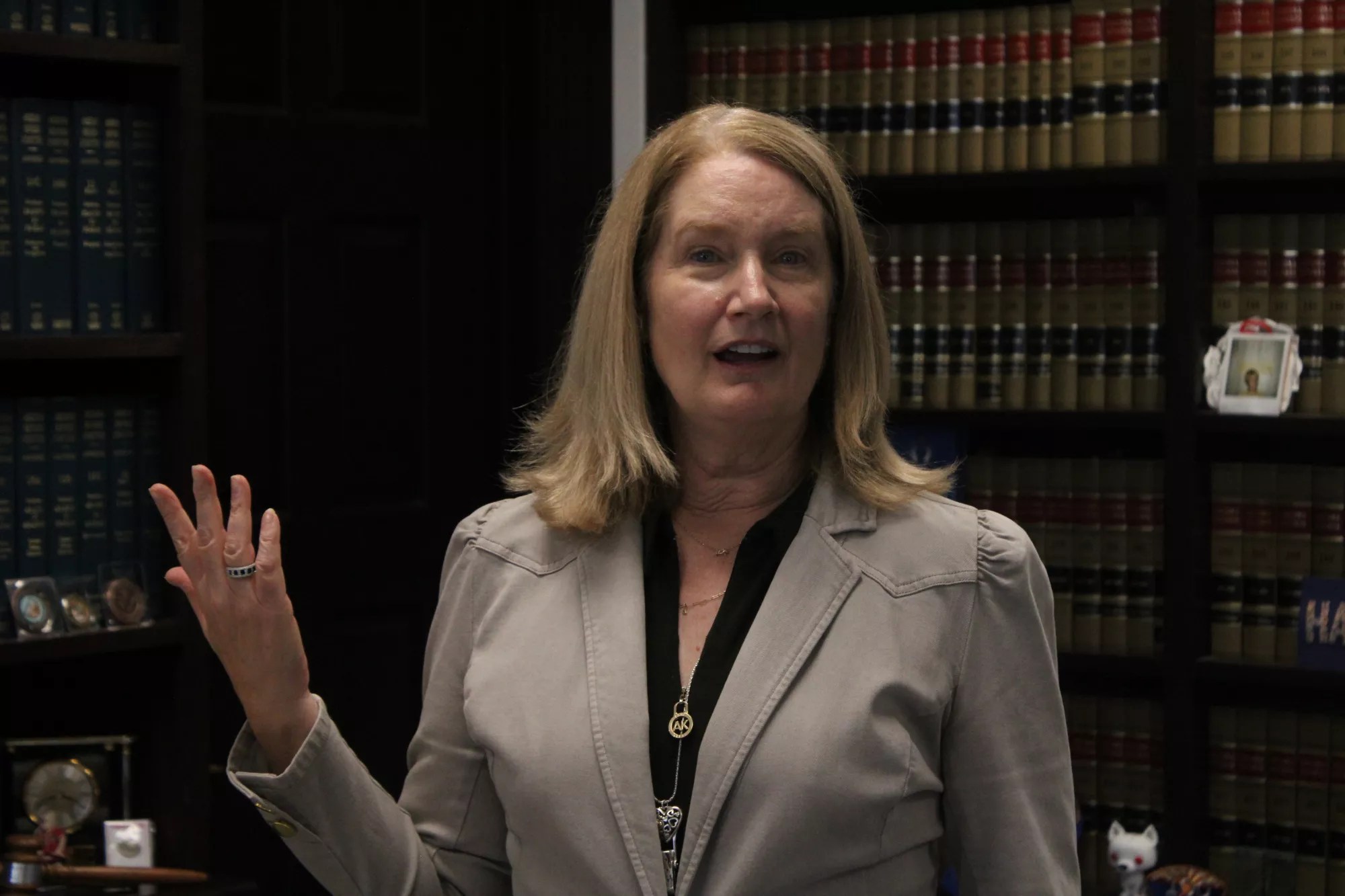

Lawmakers and civil legal aid groups are now scrambling to avert the crisis that Trump seeks to foist upon them. They are batting around ideas and pushing for money in the state budget. At the center of that effort is an unlikely figure: Ann Scott Timmer, the chief justice of the very conservative Arizona Supreme Court.

Ann Scott Timmer, the chief justice of the Arizona Supreme Court, called a stakeholders meeting to prepare for the possible end of federal funding for civil legal aid in Arizona.

Morgan Fischer

All hands on deck

A week before the Trump administration released its budget proposal, Timmer summoned a collection of stakeholders for an “all-hands-on-deck” meeting. At the meeting were judges, lawyers, lawmakers, legal aid representatives and a staffer for Gov. Katie Hobbs – “The people who can do something about this,” Timmer said.

“My goal,” Timmer told Phoenix New Times, “was to put it on their plate.”

The Arizona Supreme Court can’t blatantly advocate or lobby for a policy. “We can get people together in a nice room,” Timmer said. “We’ll give you a cheap lunch and there you go.” But her involvement underscored the gravity of the problem.

“The fact that this was coming from the Supreme Court absolutely elevated this issue to me,” said Democratic state Sen. Analise Ortiz, who was at the meeting. “It is rare that we see the Supreme Court kind of sounding the alarm on issues like this.”

The stakeholders largely agree about the magnitude of the issue.

Arizona’s civil legal aid system is already small. Other states fund civil legal aid through a direct state appropriation, a court filing fee or both. Arizona does neither. The $16.5 million the state’s three programs currently receive from LCS accounts for 60-70% of their collective budgets. Another 8-10% comes from other federal programs. The rest comes from the Arizona Bar Foundation and other grants.

That money pays for fewer than 80 attorneys who provide civil legal aid to the entire state, Timmer said. More than a million low-income Arizonans are eligible for that aid, but the organizations that provide it can handle only about 9,000 cases a year.

“The system doesn’t work perfectly for low-income Arizonans,” said Drew Schaffer, the director of the nonprofit William E. Morris Institute for Justice. “If they can’t afford an attorney, they’re essentially relying on civil legal aid to fix those problems when they can’t afford to protect their basic health and safety.”

For Community Legal Services, whose flyers can be found in Phoenix courthouses, those legal aid services run the gamut. CLS helps domestic violence victims with protection orders and custody agreements. It helps seniors with their benefits. It aids victims of fraud, workers whose former employers have kept their personal property and people dealing with wage garnishment and car repossession.

Losing the main source of funding for civil legal aid would be “definitely a code-red emergency,” Schaffer said, one that “would mean essentially the end of our civil legal aid system as we know it.” Groninger called it “a shock to the system.”

“We’re not ready for this,” he said. “We’re not prepared.”

One solution is obvious – the state of Arizona could pick up the slack that the federal government is eager to loosen. Indeed, one product of Timmer’s all-hands meeting was a proposal to allocate $10 million in the next state budget to backfill these programs.

But in Arizona, hammering out the budget is anything but simple.

A Community Legal Services flyer on display at Maricopa County’s Arcadia Biltmore Justice Court.

Morgan Fischer

A budget solution?

The budget proposal is the project of Ortiz and fellow Democratic state Sen. Lauren Kuby, both of whom attended Timmer’s meeting. Time is of the essence.

By law, Arizona is supposed to hammer out a budget by June 30 for the next fiscal year. With a Democratic governor and a Republican-controlled legislature, that process “can be very twisted and happen very quickly,” Kuby said. Budget negotiations between Hobbs and Republican leadership generally occur behind closed doors. On Saturday, Republican state Sen. T.J. Shope wrote in the Senate Republican Caucus Newsletter that negotiations “are in the final stages” and that he anticipates a proposal hitting Hobbs’ desk “within the next two weeks.”

Finding $10 million for civil legal aid would seem a drop in the bucket of the state’s nearly $100 billion budget. However, Arizona is bracing for federal cuts across many programs, including public health grants and Medicaid. Meanwhile, many state Republicans would prefer to cut state programs (along with taxes) rather than fund more of them.

That means “we do not have a lot of extra money in our state budget to spend,” Ortiz said. “We are dealing with Republican leadership in the House and the Senate who are not prioritizing the needs of working-class people.” Kuby believes the legislature could easily fund civil legal aid by reining in other costly programs like the state’s largely oversight-free school voucher system, though convincing the GOP to sign on to that is likely a pipe dream.

It’s unclear what Republican leadership thinks of the proposal to fund civil legal aid through the state. Arizona Senate President Warren Petersen and Arizona House Speaker Steve Montenegro did not respond to a request for comment.

As for the governor, Ortiz said she wasn’t “given a clear answer about whether the governor’s office shared my priority on this issue.” Hobbs spokesperson Christian Slater wrote in a statement that while the governor’s office “does not comment on the contents of ongoing negotiations,” Hobbs “has been outspoken about the reckless, harmful” federal cuts. Slater also noted that Hobbs has made civil legal aid a priority in the past, directing Biden-era American Rescue Plan Act funds toward the programs in 2023.

At least one Republican, state Rep. Alexander Kolodin, is advocating for an alternate solution. A lawyer who has run afoul of the state bar with 2020 election lawsuits, Kolodin said he’d support “loosening the requirements” to allow paralegals and other non-bar-compliant lawyers to represent people in civil court for “run-of-the-mill” cases. “Realistically, the folks who need really complex services will still hire lawyers,” he told New Times. “But the folks who need defense from an eviction, they can have somebody who’s skilled and knowledgeable about evictions representing them.”

Expanding the ranks of people who can provide legal services is something that the Arizona Supreme Court has implemented in recent years. Arizona is a “legal desert” – the state doesn’t have enough lawyers, despite what the Valley’s many billboards would lead you to believe – and the Court has authorized around 60 paraprofessionals to operate “in some spaces” of civil law, like family law. But while they are generally more affordable than a full-fledged lawyer, paraprofessionals aren’t exactly cheap, either.

“We cannot say, ‘Oh, we’ll find another pathway to help give people more support,'” Ortiz said. “It has got to be both. We need the funding.”

A lot of hopes and even more livelihoods may hang on that funding coming through. Schaffer called a $10 million budget infusion “a modest incremental first step” to “avoid a complete catastrophe and disaster.”

Timmer told New Times that she’d “love it” if the state funded civil legal aid, though she (more than most) knows that policy decisions are the prerogatives of lawmakers. The Supreme Court’s meeting “accomplished one goal that I really wanted,” she said. “Which was to put this on the radar screen of the people who can do something.”

In the meantime, civil legal aid organizations have no choice but to plow forward and hope that the money will be there in the end.

“We have to just keep going every day,” Bridge said.