Gage Skidmore/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Audio By Carbonatix

After an assassin killed Christian nationalist commentator and Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk last year, right-wingers successfully drummed hundreds out of their jobs for their supposedly heinous comments about Kirk’s death. Some of those people had merely quoted Kirk’s own words.

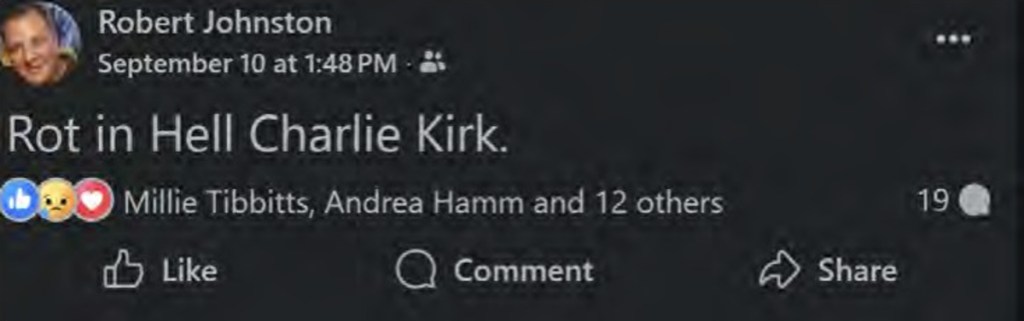

Robert Johnston Jr., a legal secretary at the Gila County Attorney’s Office, was one of those fired, getting canned by county attorney Bradley Beauchamp five days after Kirk’s Sept. 10 murder. The reason: Johnston had posted “Rot in Hell Charlie Kirk” on his personal Facebook page soon after learning of the killing.

Last month, Johnston filed a federal lawsuit against the county over his dismissal, claiming it violated his First Amendment right to freedom of speech. Johnston, who worked in the office’s Payson branch processing misdemeanors, also alleges that Beauchamp ginned up false sexual harassment allegations against him when it seemed like Johnston’s Kirk post wouldn’t do the trick. Johnston is asking the court to reinstate him and to award him unspecified damages from the county and Beauchamp for wrongful termination and retaliation.

Neither Beauchamp’s office nor Johnston’s attorney returned calls seeking comment on the lawsuit.

Johnston’s complaint describes how “minutes after learning of the Kirk shooting,” he took a bathroom break, during which he used his personal cell phone to post his rather tepid message to his “friends only” Facebook account. But the internet being what it is, screenshots of Johnston’s post eventually made it up the food chain to Beauchamp, a Republican first elected in 2012 to office in the rural county northeast of Phoenix.

In Johnston’s termination letter, which was included among hundreds of pages of exhibits in the lawsuit, Beauchamp explained that as county attorney, it was his “statutory duty to prosecute such heinous crimes with the support of my staff,” telling Johnston that the comment was “totally inappropriate and cannot be tolerated.”

Johnston appealed the decision. In a letter to the Gila County Personnel Commission, he argued that his termination was “arbitrary and capricious” and violated both the county’s merit system rules for public employees as well as Johnston’s right to freedom of speech under the Constitution.

“My comment ‘Rot in Hell’ is the antithesis of ‘Rest in Peace,’” Johnston argued in his appeal letter, “and to infer anything else is to inject your own political presumptions.”

Johnston asserted that he was a rather low-ranking clerical drudge who didn’t even work in the county attorney’s main office in Globe. He added that in his more than two years in the office, he’d been an exemplary employee, with no reprimands. He also cited the 1987 Supreme Court case Rankin v. McPherson, in which the high court ruled in favor of an employee in a local constable’s office who, after the unsuccessful 1981 assassination of President Ronald Reagan, had said, “If they go for him again, I hope they get him.”

The Supreme Court ruled that the statement was protected by the First Amendment, partly because it involved a matter of public concern, was not a threat to the president’s life (which would be illegal) and did not dramatically interfere with the effectiveness of the workplace. As the modern internet did not exist in 1981, the details of the Rankin case differ considerably from Johnston’s. But Johnston’s impassioned assertion of his First Amendment rights may have given Beauchamp some pause.

On Sept. 26, Beauchamp amended the termination notice, adding vague allegations of sexual harassment involving comments Johnston allegedly made to an unnamed coworker the previous August. True or not, the allegations opened up a proverbial can of worms for Gila County’s top prosecutor.

Court documents

Hoo-has, sugar daddies and man whores

According to a transcript of Johnston’s Oct. 21 hearing before the county personnel commission, the late-coming sexual accusations backfired on Beauchamp. The hearing produced accounts of an office environment that read like a cross between Duck Dynasty and White Lotus — emphasis on the former.

In his amendment to Johnston’s initial firing letter, Beauchamp tacked on three allegations of Johnston making inappropriate comments to a female coworker, saying these were also grounds for immediate dismissal. The comments involved the woman possibly leaving her husband, Johnston offering to be her “sugar daddy” if she did, and telling her, “If you ever want to take advantage of me on that couch” in the woman’s office, “you know where to find me.”

During the hearing, Johnston denied that he’d made the comments. He called the accusations “absurd” and claimed that the county attorney’s office was desperate to smear him with false allegations because they knew his First Amendment claim was valid. Ironically, these accusations opened up an unusual line of questioning from Johnston’s attorney, Joshua Black, who elicited a surprising admission from Chief Deputy County Attorney Joseph Collins.

Under questioning, Collins admitted taking a bet from another prosecutor as to whether he could get the word “hoo-ha” into the court record. “One of our defendants had put drugs in her vagina,” Collins told the commission. “And so I made the comment that she had drugs in her hoo-ha.” Collins said the other attorney bet him $100 that he wouldn’t repeat the phrase “hoo-ha” in court during closing arguments. Collins did, apparently winning the bet.

Asked during the hearing if he thought it was appropriate to use the word “hoo-ha” in court, Collins replied, “Judge didn’t object. He didn’t do anything about it.” During another part of his colorful testimony, Collins described his investigation into the sexual harassment claims against Johnston, stating that “Johnston has the reputation of being a man whore in the office.”

That remark allowed Johnston to rebut that characterization during his own testimony. He said it couldn’t possibly align with his alleged comment about being a sugar daddy, which Johnston defined as “someone who pays for companionship.”

“You heard testimony that I’m sort of a man whore,” he said. “Ok, so I don’t have a problem apparently getting female companionship whenever I want, but I need to offer someone that I’m going to be a sugar daddy? I don’t believe so.”

Collins’ “man whore” comment caused the commission’s chairperson, Christa Dal Molin-East, to observe that there “might not be the best environment in that office.” Commissioner Jesse Leetham quickly agreed.

“I was just about to go down that list. We have a deputy county attorney who’s made a bet to try to get the term hoo-ha into a closing statement, as if it’s a joke, the courts are a joke. That sets a precedent for where we are. And that’s why I said this behavior occurred and it probably continues,” Leetham grumbled.

With egg on face, the county attorney’s office agreed to strike the sexual harassment claim before the hearing’s conclusion, though it remains a part of the public record in the case. If Johnston’s claim goes to trial, the deputy county attorney may get to repeat the word “hoo-ha” in federal court, though he won’t be scoring another C-note for it.

Despite ditching the sexual harassment claims, the commission ultimately rejected Johnston’s First Amendment arguments. It upheld his termination, finding that his “Rot in Hell” post was made during work hours and citing testimony from other employees supposedly bolstering Beauchamp’s contention that the post would hurt his office’s reputation with the public and “cause disharmony among staff.”

Gila County Attorney’s Office

Protected or not?

Is telling Charlie Kirk to rot in hell protected speech? For Johnston, it may be.

Attorney Alex Morey, a free speech expert with the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Freedom Forum, said Johnston may have a viable claim in large part because he was a public employee. If Johnston had worked for a private company, Morey said, he would have had little or no recourse on purely First Amendment grounds.

“That employer has their own First Amendment right to decide whether or not they want to be associated with you as an employee,” Morey said, adding, “They have a right to fire you if you say something that they dislike that doesn’t align with their values as an employer.”

By contrast, the First Amendment constrains government employers in how they can censor or burden speech. But that doesn’t mean public employees have carte blanche.

The Supreme Court made that clear in its 2006 decision in Garcetti v. Cebellos, which involved a deputy district attorney in the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office. In that case, the deputy prosecutor claimed he had been retaliated against for writing a memo criticizing a faulty affidavit for a warrant. But the court found that the prosecutor’s speech was pursuant to the dictates of his job, so the First Amendment did not shield him from discipline.

Under Garcetti, government employees acting within the scope of their job duties “basically don’t have First Amendment rights,” Morey said, even if they are speaking on a matter of public concern. In the Johnston case, the court would have to “scrutinize the facts” to determine what actually happened.

“Was this employee causing serious workplace disruption or are we seeing viewpoint discrimination and political retaliation in the workplace?” she asked.

To answer this question, she said the litigation would have to use the discovery phase to fully flesh out the details of what happened, delving into the emails and texts of Beauchamp and his employees. Considering the testimony of Beauchamp’s underlings during Johnston’s appeal to the Gila County Personnel Commission, that could prove eyebrow-raising.

For his part, Johnston points out in his complaint that “nothing in or related to” his post “indicated (he) was employed by, or had any connection to, the Gila County Attorney’s Office,” nor did it “advocate or approve of any unlawful conduct.” Neither was there “evidence that the post was known to the general public in Gila County or that it impaired or was likely to impair the efficiency or operations of the Gila County Attorney’s office.”

The complaint notes that Beauchamp testified at the appeal hearing that he interpreted Johnston’s post as “celebrating the murder of a man in front of his wife and children,” though it adds that Kirk’s family members did not actually attend the event where he was killed.

Per his complaint, Johnston “suffered prejudice by being falsely accused” of sexual harassment. It also says he suffered “a reduced standard of living and becoming more ‘isolated’ living in the small community of Strawberry, embarrassment and humiliation from being fired, worry about how he can support himself, sadness, and emotional distress from the loss of his job and the highly valued relationships he had enjoyed with his co-workers at the Gila County Attorney’s Office.”

Johnston is still unemployed, his complaint alleges, and “has poor prospects for finding suitable new employment near his residence in Strawberry.” Johnston claims that he “has applied for numerous jobs as a paralegal but so far has not gotten a single interview and is subject to compelled self-publication when he is asked about his employment history and must truthfully admit he was fired from his last job.”

As a last note, Johnston’s complaint points out that “the hateful words ‘Rot in Hell’ have been freely and openly spoken by the current President of the United States about his political enemies.” Then again, U.S. presidents — especially the current one — can get away with much more than county legal secretaries.