City of Glendal

Audio By Carbonatix

Mark it down as a rookie mistake, an unforced error or both.

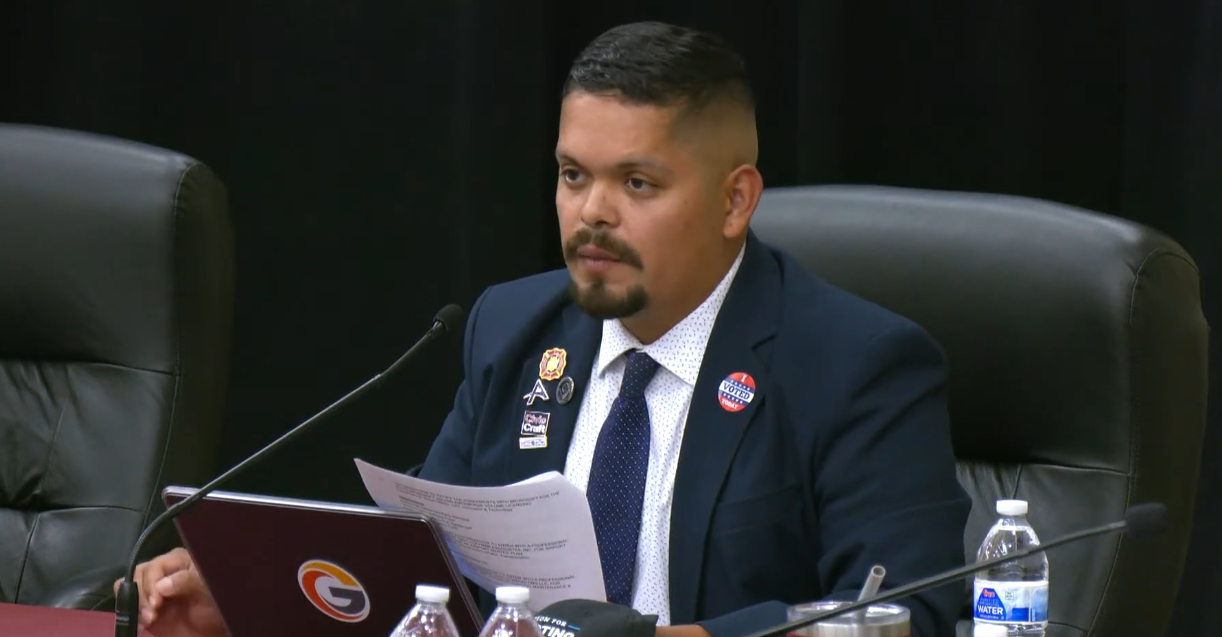

Recently, freshman Glendale City Councilmember Lupe Conchas has crusaded against the city’s generous monthly stipends for councilmembers. The stipends — $1,350 a month on top of a yearly salary of $34,000 and another $33,000 a year for district expenses — amount to a “slush fund,” the 33-year-old Conchas said in an interview with ABC15 last week. Conchas told the station that he stopped taking the extra cash in June because “there’s no accountability on how these funds are spent” and that the stipends should be axed.

Months earlier, though, the Democrat took to social media to directly solicit money on his personal Facebook page, asking people to send him money “through ApplePay and Zelle” to help him address “major home repair issues.” One campaign finance expert said such an arrangement — people giving money directly to a politician, with no transparency as to who gave how much — creates “an appearance problem.”

In late October, Conchas posted on Facebook to say that his family had been hit with a home repair calamity that included $34,000 in plumbing repairs, leaving them without a working shower. Now he needed to come up with another $10,000 to repair the home’s sewer line. He had exhausted “all financing options, my savings, my home owners insurance,” he wrote, so he had no recourse but to appeal to the public.

“Any contribution, no matter the amount, would mean the world to us as we try to get back on our feet and restore basic necessities in our home,” Conchas pleaded.

Several commenters expressed sympathy with Conchas’ plight, offering to help and asking if there was a link to a site where they could donate. Conchas wrote that he was “working on a GoFundMe page” but directed them to use Apple Pay and Zelle to send him funds in the interim. One commenter said she had “sent a little something,” adding, “I hope it helps.”

Asked by New Times about the solicitation, Conchas told New Times that he put up the post “out of desperation.” When he created that post, he was “really at my breaking point” and had even been “crying in my room” over the family crisis. His plumbing issues were so dire, he said, that family members — including his mom and siblings — had to shower at a local gym. His home was built in the 1960s, and “the plumbing line was completely disintegrated,” forcing contractors to dig up his dining room, his living room and his bathroom.

He added that he never put up a GoFundMe account but did accept donations for home repairs from friends and family, which he described as “less than $1,000.” He later emailed New Times a thank-you note sent to his contributors, listing the names of the donors and the amounts they gave, totalling $650.

“After I received just a few donations from friends, I decided that I would just stop my pursuit of getting donations from people,” he told New Times.

Sometime after New Times first spoke with Conchas, the post asking for home repair funds was removed from his Facebook page. Conchas told New Times that he removed the post “because I’m no longer seeking donations anymore.”

Conchas said he did not solicit donations in his role as a councilmember but as a harried head of household with a house from hell. But one of his objections to the monthly stipend — which includes a $450 car allowance and $900 for incidentals — is that councilmembers did not have to submit receipts or otherwise report how they spent the money. Instead, the money is just added to their paychecks.

Wasn’t he worried about a similar issue with asking the public for donations for personal use? After all, even if the request is done in a time of need, someone with ill intent could use it to evade campaign finance requirements or even engage in bribery.

“No, I’m not concerned about that,” Conchas said. “I think it’s because my community trusts me, and I’ve always led with transparency, accountability and ethical leadership.”

Conchas, who was elected in July 2024 by a mere 70 votes, said he did not consult the city attorney about the post and said he would disclose the donations on the yearly financial disclosure statement he is required to submit to the city. He explained that his home situation was back to normal, with the repairs funded through financing.

Appearances can be misleading

While he said he’s not the kind of person “who would ever sell my influence or sell any of my values,” Conchas admitted that “in hindsight, could I have thought about that perception from other people? Yes.”

Tom Collins, the executive director of the Arizona Citizens Clean Elections Commission, agreed. Speaking generally and not about Conchas specifically, Collins said, “I don’t think there’s a strict ban” on asking for donations to address a personal situation. However, he added, “You might not want to be in a position where it looks like you’re using your official position to obtain the donation.”

Collins pointed to two Arizona statutes, A.R.S. 38-504 and A.R.S. 38-444. The former proscribes a public officer from using their position “to secure any valuable thing or valuable benefit.” The latter makes it a class 6 felony for a public official to “knowingly” ask or receive “any emolument, gratuity or reward, or any promise thereof, excepting those authorized by law, for doing any official act.” In other words, a quid pro quo.

Arguably, neither would apply to Conchas, given what is known of his solicitations. Still, Collins pointed out that these laws “are certainly not encouraging folks to go out and try to obtain money.” Even if a city official was able to do so in such a way “that it doesn’t implicate your office at all,” he said it would be best to consult with the city attorney first. For a politician, even the possible appearance of impropriety or any inkling thereof could prove problematic.

“If you ask me if you ought to do it,” Collins said, “my answer would be, ‘Unless you would like a news organization to ask you about it and have a very good answer, you probably don’t want to do it.’”

Conchas’ commitment to ending the Glendale City Council’s so-called slush funds does appear genuine.

He raised the issue of the stipends and the car allowance with his fellow councilmembers during an Aug. 26 city council workshop, noting that the decision to take lump sums of compensation had been made in 2022 by the city manager at the time and discussed in executive session. The council had never considered the matter publicly, much less taken a vote on it.

Three years before that, Glendale residents had overwhelmingly rejected a $20,000 pay raise for councilmembers. Since the rule change, the payouts had totaled “more than $300,000,” Conchas said at the workshop. He suggested putting the item up for a council vote so that the public could weigh in on the rule. The council could either keep it as is, enact strict guidelines or sunset the policy altogether.

Councilmember Bart Turner agreed with Conchas’ criticism of the stipend and car allowance, calling it a form of “double-dipping” and saying that he had never taken the money. But other councilmembers, including Glendale Mayor Jerry Weiers, defended the payouts, saying they needed the money to pay for copies, car trips and coffee with constituents. By the end of a cantankerous session, the question remained unresolved.

“If we believe in accountability, we cannot hide compensation behind closed doors,” Conchas told his fellow councilmembers at one point. He said he wasn’t arguing that the payments were illegal, but “just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s good policy.”

The same could be said of Conchas’ personal solicitation message, of course. That comes with the territory of holding elected office.

“You’re an elected official, you’re asking for money, so you should have already accepted the fact that there’s going to be an appearance problem,” Collins said. “You’ve got to be ready to deal. If you didn’t think there was going to be an appearance problem, then I’m sorry, but that’s a little naive.”

This story is part of the Arizona Watchdog Project, a yearlong reporting effort led by New Times and supported by the Trace Foundation, in partnership with Deep South Today.