Google Maps

Audio By Carbonatix

Quietly but quickly, Phoenix has become one of the nation’s hotspots for a booming economic and technological phenomenon of late-stage capitalism: data centers – the boxy, sprawling farms of wire and silicon going up everywhere around the Valley.

Some of Arizona’s leaders have championed the economic benefits of the large facilities, which house networks of servers, storage devices and other equipment used to process and disseminate huge amounts of data. But others are ringing alarm bells that the cost to feed these techno-futurist factories is simply too high – and the rewards are reaped by too few.

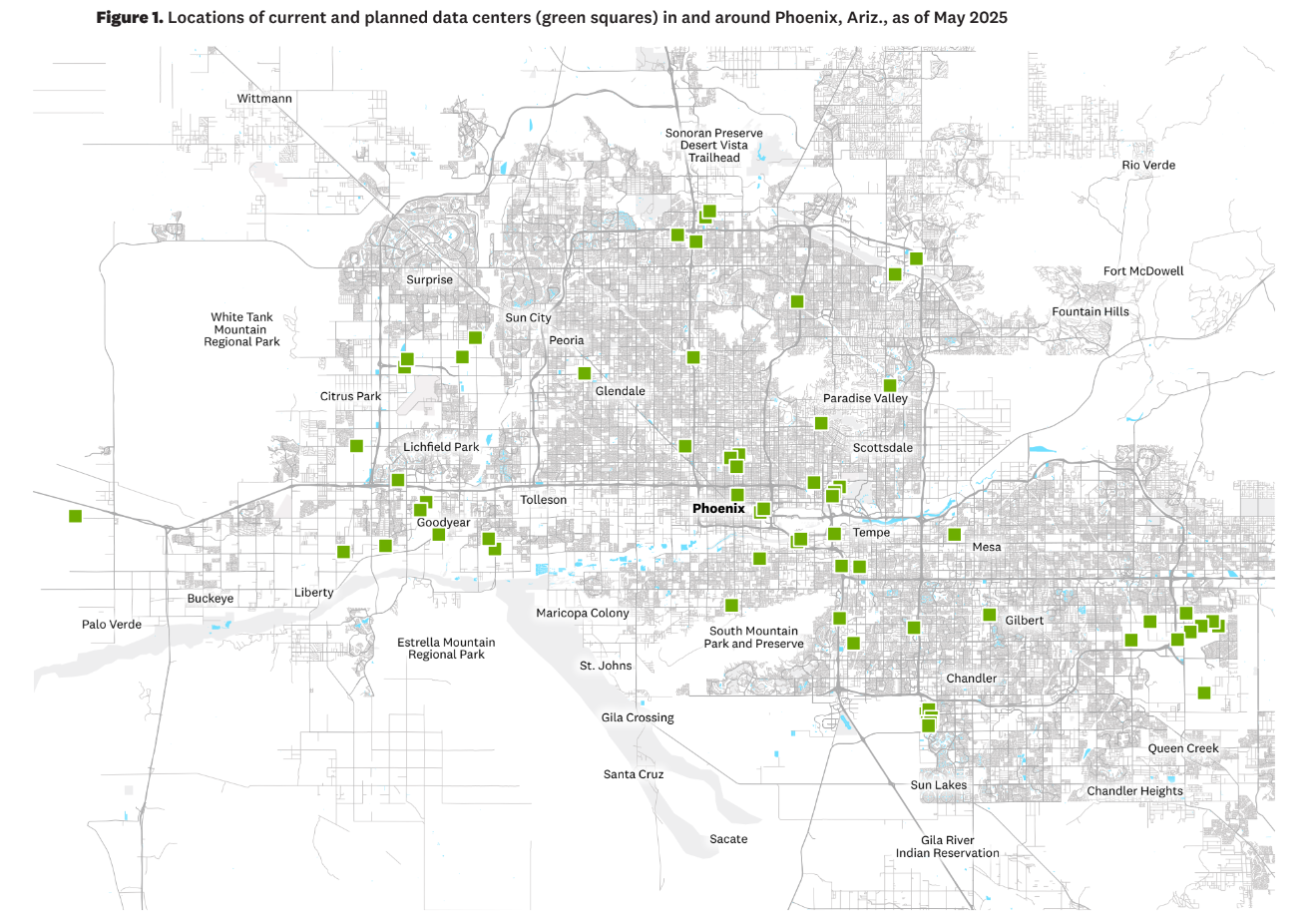

Those alarms were underscored by a new study from environmental nonprofit Ceres that was released on Tuesday. Using the Phoenix area as a case study for analysis, the “Drained by Data: The Cumulative Impact of Data Centers on Regional Water Stress” study attempts to quantify the extensive water and electricity resources that these data centers will require. It argues that a surge of data centers – 124 that have been built or are in planning phases – could have a serious impact on the already drought-stricken Phoenix. It’s part of a larger national trend: Bloomberg has reported that about 58% of U.S. data centers are in areas with high levels of water stress.

The study’s conclusions are jarring at first glance. It found that in the next six years in Phoenix, water used by data centers to cool their technology will jump from 385 million gallons a year to 3.7 billion per year – an increase approaching 900%. It also concluded that in the Valley, the water used indirectly (such as to generate electricity to power the facilities) will jump from 2.9 billion to 14.5 billion gallons.

Overall, the authors write, the new boom of data centers could increase water stress by up to 17% in some places of the Valley.

“This analysis brings into sharp focus the growing potential for higher operating costs and disruptions, reputational damage, and regulatory risks for data center companies that rely heavily on shared and diminishing water supplies,” Kirsten James, a co-author of the Ceres report, wrote in a press release.

Several investors issued statements about the importance of the study. “As more data centers are planned and come online around the globe, we need to understand the extent their water needs could impact their business and the cumulative impacts on communities and other industries in the area,” wrote Monika Freyman of Addenda Capital.

Ceres

Shaky assumptions?

However, one local water expert has some issues with the study’s assumptions. Sarah Porter, the director of the Arizona State University Kyl Center for Water Policy, told Phoenix New Times that the report has some major flaws, calling some of the choices it made to build its analysis “objectionable.”

That starts with the report’s use of gallons as a metric for water usage.

“When someone is talking about water use by industry and they’re using gallons, they’re doing this to scare people or shake people up,” Porter said. “And that may be a good thing to do or it may not be, but it’s not the way experts think about water. We think about it in terms of acre-feet.”

An acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover an acre of land to the depth of a foot. One of them is equal to about 325,851 gallons of water – enough the serve about three households a year.

In an email, Ceres spokesperson Tamera Manzanares said the study uses both acre-feet and gallons. “Acre-feet is a common unit of measure for water managers, but other stakeholders are less familiar with that unit of measurement, so we used gallons for the graphics,” she wrote.

Porter also said that the report’s assumptions about how much water will be needed to produce power for the facilities could use tweaking. The “water intensity of power production” is expected to lower over the coming years, Porter said, and the Ceres authors “don’t explain why” they didn’t factor that in.

“What we’ve found is that water intensity for power production is already going down,” Porter said. “As SRP and APS incorporate more renewable energy in the mix, the water intensity per megawatt will go down a lot more. Even though APS has stepped back from its zero-carbon-by-2050 goal, they’re still moving toward more renewables and lower water use.”

Those issues – combined with a lack of understanding about the rules and regulations around groundwater use in the Phoenix area, which is heavily regulated by the 1980 Groundwater Management Act – lead Porter to believe that the water stress figures reached by Ceres may be overstated.

In response, Manzanaeres wrote that “the report acknowledges efficiency improvements in both power generation and datacenter cooling. She also said that “the innovations implemented by any one company may not be sufficient if there are many other data centers drawing from the same water source” and that “indirect water use is not typically being acknowledged and addressed by companies.”

But even more importantly, the analysis does not compare the projected use of data centers’ water use to other uses of water in central Arizona, which is an Active Management Area under the 1980 law. The study’s figures for direct and indirect water use by the data centers come to 11,000 and 44,500 acre-feet per year, respectively. To Porter, these numbers are not particularly eye-opening in comparison to agriculture, which uses about 580,000 acre-feet per year in the Phoenix area.

“In the Phoenix Active Management Area, agriculture is still a very big water user,” Porter said.

Manzanares said Ceres has done other studies that touch on agricultural water usage.

Sarah Porter, the director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University.

Gage Skidmore/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Data centers: Good or bad?

Generally speaking, alarming studies like Ceres’ make Porter wary of the outright villification of data centers, though she stops short of calling them an unabashed public benefit. Sometimes they offer little benefit to the local communities that house them, she said.

“There are good reasons to have data centers, and then there are not-so-supportable reasons. There are industries that need server farms nearby, and so if you want to have a big city with a thriving economy, you’re going to have to have some amount of data centers to serve some industries that need to have that facility,” Porter said. “If the demand is coming from an industry that doesn’t provide a lot of return, then I think that’s where people in the community will be less willing to accommodate more data centers.”

While data center development has been largely cheered in Phoenix, similar projects have faced pushback elsewhere. Earlier this summer, Tucson residents successfully lobbied against an Amazon-related data center called Project Blue, pointing out flaws in its promises for resource usage and convincing the Tucson City Council to back away from giving the project approval. However, the Project Blue development may live on in another form.

Porter highlighted one other oversight in the study. Its estimates comparing direct and indirect use of water to other Arizona cities were more than a bit off. Scottsdale delivers 32.5 billion gallons of water to residents per year, she said, which is far higher than the roughly 7.2 billion annual estimate in the Ceres analysis.

Manzanares said the report uses the national average household use figures for a typical American family.

“They’re making assumptions about the efficiency of people in the cities of Arizona that are quite aspirational,” Porter said with a chuckle. “I don’t know where they’re getting those figures.”