aire images/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

Water is the essence of life, and nowhere is that more clear than in hot, dry Arizona.

The Colorado River is drying up, and Southwestern states are currently engaged in contentious talks – that seem to be going nowhere – over how to divvy up the drought-stricken river’s water in the future. When the current allocation agreement expires after next year, Arizona may find itself in a tough spot, with fewer water rights than it had before.

That’s a problem, but an even bigger one lurks beneath the surface of the state. According to a new study, Arizona is using up its groundwater – water from underground aquifers – faster than any other state in the Colorado River Basin.

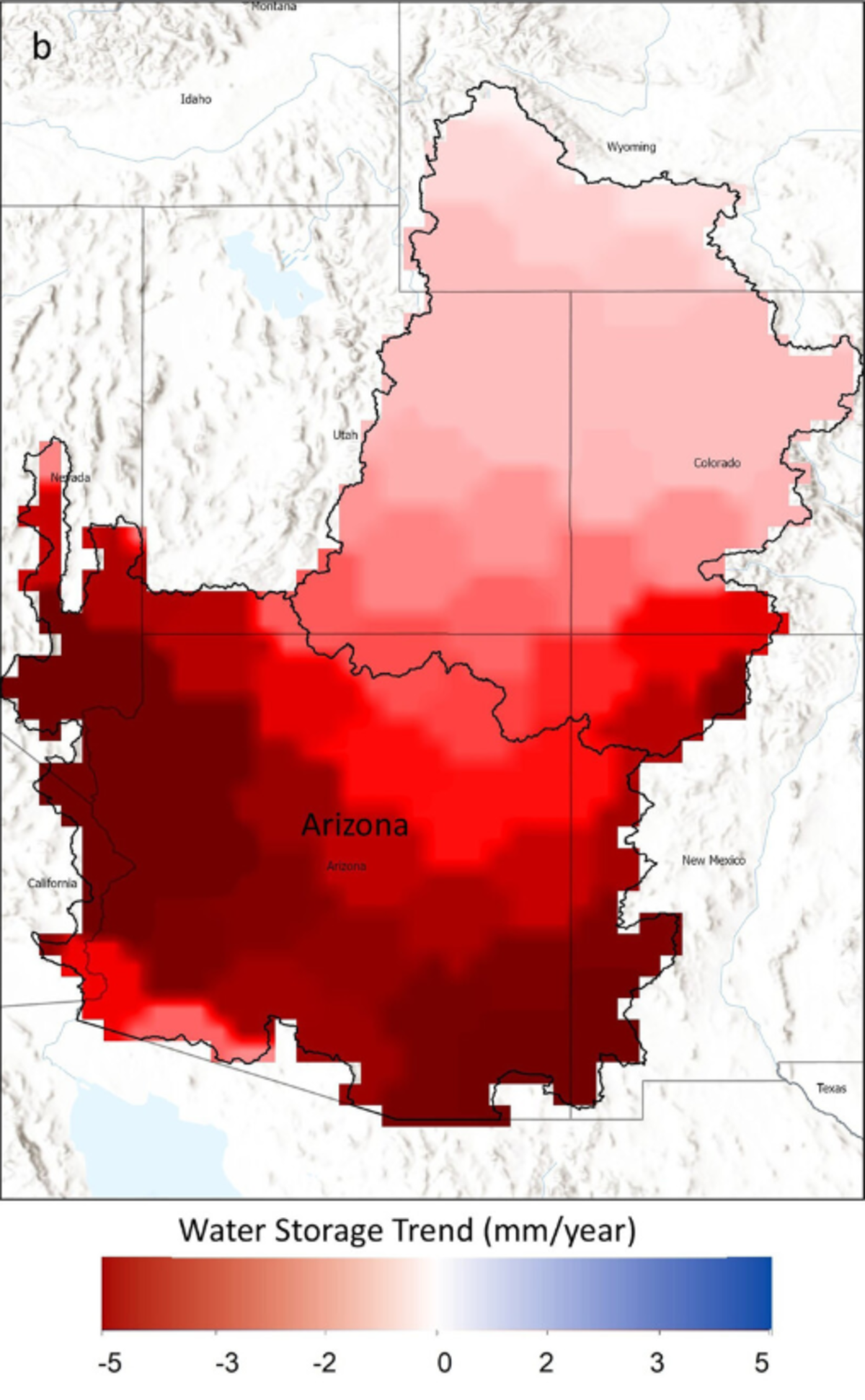

The study was published on May 27 in the peer-reviewed journal Geophysical Research Letters. In it, researchers at Arizona State University analyzed NASA data as well as Arizona Department of Water Resources figures from 2002 to 2024, showing that Arizona groundwater levels have dropped significantly during the past two decades, particularly outside the Phoenix metropolitan area.

In fact, Arizona’s groundwater is disappearing at a much faster rate than its surface water, which includes the Colorado River – and at a faster rate than other states that get a share of water from the river.

“This and previous studies have clearly demonstrated that (Colorado River Basin) groundwater is disappearing much faster than Colorado River streamflow and CRB surface water storage in Lakes Powell and Mead,” the study reads. “However, CRB groundwater receives scant policy attention relative to surface water.”

James Famiglietti, a professor at ASU’s School of Sustainability who led the research, said the study is about “raising awareness that this is happening.”

“We already use more groundwater than we use surface water,” Famiglietti said. “People don’t really realize that.”

While the dipping water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell receive a lot of attention, Arizonans rely on groundwater for 41% of their water use, more than any other source. But while the Groundwater Act of 1980 reduced groundwater pumping around Phoenix – which was causing the city to sink – few laws regulate groundwater use in other parts of the state.

That means outside of the Valley – and especially in rural southeastern Arizona, where residents are starting to panic about their wells drying up – groundwater is becoming harder and harder to come by. In that portion of the state, the ASU study shows, groundwater has dropped by more than 8 millimeters a year, a significant decline.

“Every millimeter makes a huge difference,” Famiglietti said.

Arizona State University study

Not enough regulation

Perhaps more important than the fact that groundwater is dwindling is the reason why: big agriculture. Many swaths of the state are dominated by farming interests, including big corporations that sure don’t mind being able to pump as much water as they like.

“There’s a reason why in rural areas farmers don’t want groundwater management, and that’s because they have free access to pump as much as they want,” Famiglietti said. “And that’s a hard thing to give up.”

Farming accounts for more than 80% of total water use in southeastern Arizona, the study noted, and the 15 most waterâ€intensive crops account for 71% of all crops. Water-needy pecans make up almost a quarter. On top of that, many farmers tend to use inefficient procedures like flood irrigation rather than more efficient ones like drip irrigation.

“The question for the people that resist groundwater management that I think we need to ask them is: What kind of groundwater situation do they wanna leave for their grandchildren, for their great-grandchildren?” Famiglietti asked. “Because that’s what we’re talking about.”

There have been some efforts to rein in the state’s groundwater usage. In December, the Arizona Department of Water Resources created a new active management area for the Willcox Groundwater Basin, barring anyone from irrigating unless they were already doing so before October 2024.

Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes also filed a lawsuit against the farming giant Fondomonte for violating public nuisance laws by overpumping groundwater in La Paz County. It’s the first such use of the state’s public nuisance statute to regulate groundwater usage.

However, most other efforts to mitigate groundwater loss have encountered obstacles. For years, lawmakers in Arizona have called for major changes to safeguard water in rural parts of the state.

“We have a decent groundwater protection law for our urban areas,” said Democratic state Rep. Priya Sundareshan, the minority leader in the Arizona Senate. “But we have absolutely nothing or much weaker protections in the areas outside of that.”

Earlier this year, Sundareshan was part of a bipartisan team that proposed Senate Bill 1425, a comprehensive reform bill for groundwater management in rural areas. It was developed with stakeholders from across the state. including Travis Lingenfelter, a MAGA Republican and member of the Mojave County Board of Supervisors.

But that bill never received a hearing, running into the immovable object that is Republican state Rep. Gail Griffin. The conservative southeastern Arizona lawmaker chairs the House Natural Resources, Energy & Water Committee, giving her the power to decide which water bills receive a hearing and which wither and die. The only water bills that make it through Griffin’s committee – mostly industry-friendly bills that would loosen pumping regulations – inevitably wind up vetoed by Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs.

“I think it’s also been pretty clear in these negotiations that Rep. Griffin doesn’t really have sympathy for the residents who are experiencing this,” Sundareshan said. “Her constant answer has been, ‘Well, they knew when they were purchasing.’ Basically, it’s protecting the big business corporate agricultural interests who want to pump water.”

Griffin did not respond to a request for an interview.

While Democrats and Republicans at one point were working on sorting out a bipartisan solution, Sundareshan said those days have passed. “Last year, we were negotiating and hammering out policy differences, and we thought we were moving toward the middle. We were compromising on both sides to get to a place of common ground,” Sundareshan said. Both sides met a few times in March, she said, but while Democrats made some concessions, Republicans were unwilling to move.

“We still thought Republicans cared about the rural residents and doing something about it,” Sundareshan said. “But it’s clear this year that groundwater reform isn’t going to happen.”

State Sen. Priya Sundareshan said attempts at groundwater regulation reform have been stymied by Republicans.

Gage Skidmore/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

‘Pretty dire straits’

Even in Phoenix, where groundwater is managed strictly, residents are likely to face major water issues in the next hundred years. A study from the Arizona Department of Water Resources estimated that in the next century, the Valley will experience a water shortage.

Some factors, like the Colorado River drying up from climate change, could stress groundwater even more.

“If we actually factor in these other things – like perhaps we’re going to have to rely 100% on groundwater 20 years from now – we will be in pretty dire straits,” Famiglietti said.

The Valley is adding developments at a rapid pace, and has had to stop some wildcat developments that began building without securing a 100-year supply of water, as Arizona law requires. Additionally, Famiglietti said, the boom in data centers coming to the city will drain water resources.

“The data centers need a tremendous amount of power, some of which is gonna require water to generate the energy,” Famiglietti noted. “While they don’t use as much water as agriculture, they still are going to need water.”

The ASU study concludes that Arizona and other states might not be doing enough to manage their groundwater. If they don’t step it up, the federal government may have to do it. “Where reliance on groundwater is constantly increasing, federal oversight may be necessary to ensure that groundwater resources are effectively managed in conjunction with surface water allocations,” the study reads. (Though the study doesn’t say so, the federal government hardly seems up to doing anything particularly productive under President Donald Trump.)

If anything, Famiglietti hopes the study illuminates a looming crisis hidden under Arizona’s towns and farmland. We can see a lake’s receding water line, but Arizona’s groundwater gets sucked up without such obvious signs that it’s gone.

If the Colorado River can’t be counted on, groundwater will have to be. If Arizonans want to keep having food and water – much less luxuries like swimming pools and golf courses – they might want to make sure that what groundwater we do have isn’t going to waste.