Two weeks before the start of spring break and despite good weather, the beaches and resorts in Rocky Point, Mexico, are deserted.

Reservations for the annual sojourn are reported to be minimal — resort staff and tourism officials expect another slow year. American tourists are sparse throughout town, from Cholla Bay on the west end to the posh Mayan Palace, eight miles east.

The town's boosters, condo owners, real estate officials, store owners, taco sellers, ATV renters, and residents are desperate for business, and they want people to believe the town of 50,000 is "safe." They want to talk about relative safety, how Sonora is the least violent state in Mexico and why major drug cartel activity seems to skip over the town.

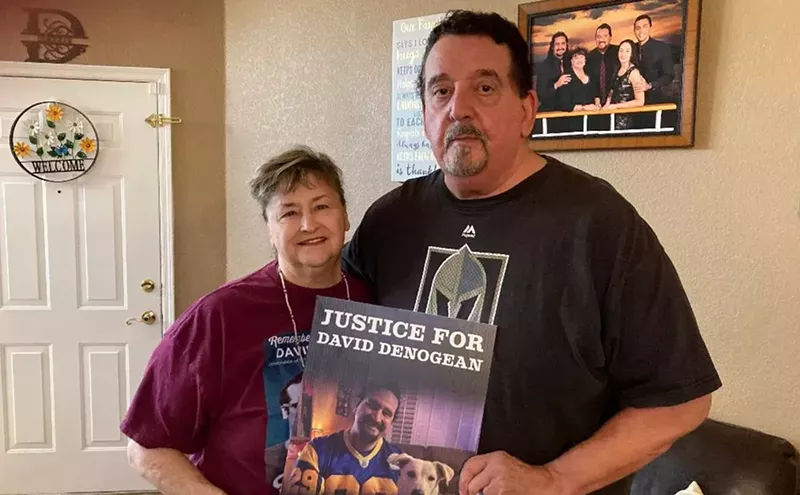

No wonder, then, that Rocky Pointers don't want to chat about the August shooting of a tourist in the popular Malecon portion of the town's Old Port marina.

Asking around about it, New Times was told by several businesspeople that they weren't aware of the murder. Others misdirected reporters, saying it did occur, just not where New Times had been told it happened.

"Take good pictures, tell a good story," urges one man at a roadside food stand.

"You're digging shit up so nobody comes here," says another, miffed at the questions. "We need people to come!"

It's late afternoon on a Friday, toward the end of another beautiful day in Old Port. The temperature is a perfect 70. A slight breeze carries smells of sea, fresh fish, and dust at Malecon, the quaint hillside of seafood markets and shops still under renovation. Earthmovers crawl across the narrow streets of packed dirt between the open-air restaurants, as hawkers wave their freshly caught shrimp, begging for customers. But there are few of them.

Only a couple of small groups of Americans wander through the area, looking more like they're taking a tour of a construction site than enjoying a vacation.

Malecon is tranquil this evening — unlike on August 22, 2010, when Juan Antonio Rodriguez Nogales was killed in front of his wife and child.

The slaying is merely one of tens of thousands since Mexican President Felipe Calderon declared war on the country's drug cartels four years ago. But it's noteworthy for a few reasons — the main one being its location.

The site of the murder wasn't some dark alley. It's on the main drag into Malecon, in a popular boat-launch yard next to an ice cream store. A typical tourist spot.

The brutal assassination was of the very type that has been keeping Americans away. But what potential Rocky Point visitors also may find interesting — may even find solace in — is the victim's identity: He was a Spaniard visiting from Juárez, not an American.

As news reports in Mexico and, later, the United States detailed, the 47-year-old man had been washing his boat in the marina with his wife, Sylvia, and their 14-year-old son. He was a businessman from Spain who'd lived in Juárez for the past 14 years and had been in Rocky Point on vacation for a few days.

About 8:30 p.m., his wife later told police, a Jeep Cherokee rolled up and four hombres armed with assault rifles got out, demanding that her husband go with them. He refused and started to run away; he was hit by seven bullets. Investigators found 15 shell casings in the dust of the boat yard. No one else was shot.

At the sandy boat yard that sprawls in the shadow of an unfinished multi-story building, one man says he saw the whole thing. A couple of other people said they knew general details about the incident and pointed out a spot in the dirt near a low, white wall where they said the body fell. New Times is withholding their names — because people who talk about cartel activity in Mexico often end up dead.

The witness says he took cover behind the big rear wheel of a tractor when the shooting erupted. Then he saw the killers' vehicle, which he says was a Ford Bronco, not a Cherokee, drive through the lot and leave through a back exit.

Authorities didn't arrive at the scene for a half-hour, he says. That claim couldn't be verified, but it's bolstered by the suspects' ease of escape, when only two main roads lead out of town.

The witness follows his story of the Malecon murder with the ironic pronouncement: "This town is fine. No problems here."

Clearly, though, there are problems — they just haven't affected Americans. Yet.

As the state's universities gear up to go on spring break next week, there's no way to determine whether Arizona's nearest beach town is safe, or will be safe, for visitors.

What can be said is that the town hasn't had the problems of, say, Acapulco, where shootouts and shallow graves with headless bodies have become the norm. And it's nowhere near Juárez, which last year broke its own record as a violence capital, recording more than 3,000 murders.

Rocky Point has been a pocket of tranquility in Mexico — and exceedingly safe. For Americans, anyway.

Yet this is the third-straight season of bad business for Puerto Peñasco (its Spanish name). The Great Recession and, now, the limping U.S. and world econonomics have taken their tolls. But the main factor in the ghost-town effect is fear.

Tourism officials report that bookings for spring break keep falling, from 54 percent of condos and hotel rooms rented in 2008 to 35 percent last year. Resort reservations for the middle weeks of March — in the mid-2000s, resorts might have been fully booked months in advance — were running about 30 percent to 40 percent in late February, despite heavy discounts.

Border crossings at the Lukeville port of entry (measured northbound by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency) fell again last year, from 347,000 vehicles in 2009 to 313,000 vehicles in 2010. Three years earlier, 451,000 vehicles crossed.

Mexi-phobia rules up north in the States, where reports of mass murder, mutilated corpses, and a drug war in Mexico have made former Peñasco fans reconsider their trips.

"The so-called drug war is . . . not here," says Johnny "Vegas" Hostak, co-owner of Al Capone's Pizza and Beer in Rocky Point. "When I hear well-educated, affluent people agreeing with the media, it's really scary. Some of these people have turned their backs on Mexico."

Mexican fly-in destinations saw a slight increase in tourism in 2010, following two down years, but Rocky Point, a jewel-in-the-rough on the north shore of the Sea of Cortez, continues to experience a massive decline in visitors. The town's boosters and some visitors who make the trip seem baffled, even annoyed, by the lack of interest these days.

"People are afraid," scoffs George Camacho, a Tucson chiropractor strolling in the Malecon with family members. "It's Governor Brewer talking about headless bodies."

Promoters and businesspeople often talk about the "perfect storm" of negative factors driving down tourism. First, the recession in 2008. Then the swine flu in April 2009, a disease that appeared to stem from Mexico and reportedly killed young and old alike. The flu turned out to be no big deal, but not before the fear of it devastated Mexico's resort towns, including Rocky Point.

In June 2009, the U.S. government began requiring passports for all citizens returning from Mexico. With only about a quarter of Arizonans holding passports, the rule had an immediate, drastic effect on Rocky Point tourism. (Border agents say their policy is to never refuse entry to a U.S. citizen, however, passport or not.)

As these developments caused Americans to think twice about traveling to Mexico, the news media depicted the country's violence as the stuff of a never-ending series of Saw sequels. Sometimes Mexico appears worse off than the war zones of Iraq or Afghanistan, with reports of mass graves, decapitations, dismemberments, and a government powerless to stop the perpetrators.

These days, it's impossible not to think about the unrestrained violence in Mexico, at least a little, when you're south of the border. Visitors to Rocky Point also spoke of peer pressure they received from friends and family at home when planning their trips.

"Everybody thinks we're nuts," says Steve Phillips of Eugene, Oregon, an RV owner camping at the Playa Bonita RV park on Sandy Beach. "We thought real seriously about not going here. But, no problema, as they say."

Indeed, millions of Americans have visited Rocky Point in the past few years (including repeat visitors) without incident.

Judging by news reports and other sources, 1991 was the last year that an American was murdered in Rocky Point — and that was a bizarre, well-publicized case involving the victim's husband and his transsexual lover.

In hindsight, it was more dangerous last year for Arizona State University students to walk around Tempe at night: Two were killed in separate robberies.

Even for Mexicans, Rocky Point isn't a major danger zone. It's certainly much safer than Nogales, which last year suffered a murder rate twice that of America's most dangerous city.

Yet it's unclear precisely why Rocky Point hasn't experienced as much cartel violence or banditry as other Mexico locales. And that's the sort of question that can keep make even an adventurous visitor antsy.

Fear is personal and often irrational, and it can be difficult to convince someone who harbors a lot of it that they will be as safe as in their hometown. But people who avoid Mexico are missing out on something. Not just the beaches and drunken escapades (though there's something to be said for those, too), but a real cultural experience.

While you're sitting on the couch, watching the alien beauty of a place like Malaysia or Malawi on HDTV, just 200 miles from Phoenix is a world that combines the seaside beauty of San Diego with the cultural wonders of Latin America. You get to practice another language (one that might come in handy in Arizona), meet different people, sample local dishes, and come to know better the world you live in.

In reporting this article, no heed was paid to several admonitions in last year's State Department warning about traveling in Mexico: For a few days in December, and again in February, we drove nearly everywhere in Rocky Point both day and night, sometimes alone, and sometimes on infrequently used roads.

Nothing seemed dangerous, whether having a shrimp cocktail at a fish market, conducting an interview in a barrio, or driving around at night in the dark amid the mostly unoccupied homes in Cholla Bay.

New Times drove through the Pinacate Biosphere Reserve, a national park off Highway 8 that's promoted with small billboards in nearly every hotel in Rocky Point these days. Though blog sites suggest hiring a guide for the 40-kilometer loop through the park, considered one of the most heavily cratered places on Earth, it's not really necessary. El Elegante, which could be Meteor Crater's volcanic twin, is an awesome sight.

Driving around this part of Mexico and hanging out in Rocky Point was the Gruesome Adventure That Wasn't. That is, it was all good.

Of course, the extra risk inherent in travel to a so-called Third World country must be accepted. Like riding a motorcycle, which is statistically more dangerous than driving a car, a mental adjustment must be made.

"If you're not familiar with the country, there's some uncertainty about travel," says Margie Emmerman of the Arizona-Mexico Commission. "People who travel more frequently are savvier about how to travel and where to travel. It's about having the right mindset."

Emmerman says she recently drove from Phoenix to Hermosillo, southeast of Rocky Point, without incident. But she has her limits: She says she wouldn't drive there alone.

The thought of driving south on Highway 8 from Sonoyta to Rocky Point, whether alone or not, holds many potential visitors back.

"I wouldn't mind going to Rocky Point," says a former Phoenix resident who says she practically "grew up" there because of her family's frequent visits. "But the drive there — I'm not sure I would do that now. I don't like those long stretches of nothing in the desert."

Rick Busa, a Rocky Point resident from Phoenix who runs a sports foundation in the Mexican town, says his wife and daughter frequently motor from Sonoyta to Rocky Point without worry.

Busa knows the United States isn't necessarily safer: A few years back, he lost a 17-year-old daughter in a vehicle collision just outside of Buckeye that also killed another teen. They were coming back from Disneyland.

Rocky Point's earliest history as a tourist destination involved an associate of Al Capone's.

It's ironic, then, that so many people are scared to visit it now because of crime related to the prohibition of drugs.

According to published accounts, the mob boss' associate, hotel owner John Stone of Ajo, was turned on to the area by Mexicans who wanted to promote excellent fishing and recreational opportunities. In 1929, Stone built a hotel, a well, and an airport that provided direct flights to and from Phoenix and Tucson. After a falling-out with the fledgling town's leaders, Stone was driven from the area — but not before setting fire to his hotel and blowing up the well.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the 65-mile Highway 8 from Lukeville to Rocky Point during World War II, in case America needed to use the Sea of Cortez port in its fight against the Japanese. (The United States had been prepared to take Rocky Point and the surrounding area from Mexico in the mid-1800s for a paltry sum. Mexico persuaded its more-powerful neighbor to the north to let it retain a land bridge to Baja California).

The region turned into a partying mecca in the 1970s, with the development of beach homes from the craggy peninsula of Cholla Bay to the smooth beaches of Las Conchas.

Many longtime Arizonans can recall the litter box of used fireworks and beer cans known as Sandy Beach, a place strewn with campers and drunk ATV-ers. Articles from the early 2000s depict a town struggling to cope with its own growth and popularity, with police making half-hearted crackdowns on the craziness. At the same time, it's been a magnet for families from Arizona and elsewhere who stick to the quieter beaches and condos.

The town grew up, sprouting high-rise condos on Sandy Beach and a resort experience. Circle Ks compete with the Oxxo convenience stores and Pemex gas stations. Houses are stuffed into Cholla Bay, some with virtually no setback from the road. Americanized, guard-gated neighborhoods east of Las Conchas sprawl past an estuary along back roads (upon which no American ever has been kidnapped or murdered — that New Times could ascertain, anyway) to the Mayan Palace area, which contains a swanky resort and expensive-looking, mostly half-built homes. Most of what is considered Rocky Point or Puerto Peñasco is far removed from the gritty township.

Serious problems with overdevelopment in Rocky Point have become more acute now that hordes of tourists have stopped coming, says Fausto Soto, the city's director of international relations and tourism.

During the height of the "feeding frenzy," as Soto puts it, condo towers like the Sonoran Spa and Sonoran Sea, both of which contain more than 100 condo units, sold out just four hours after auctions began.

"We didn't really develop a real tourist industry, because there were no hotels," Soto says. "We called it 'real estate tourism.' More than visitors, buyers were coming down."

(Plenty of people were suckered into bad real estate deals, but that's a different story.)

Then came the aforementioned perfect storm of problems, which had a snowballing effect. Rocky Point never was exactly "safe." But, Soto says, suddenly the perception of danger spun out of control.

During spring break 2009, for instance, the University of Arizona issued a warning against traveling to Mexico — even though its women's golf team was scheduled to play a tournament at the Mayan Palace. When city boosters reminded college officials about the golf tourney, UA nearly pulled its players out, Soto says. Town leaders managed to convince the university that it was safe to visit, and the university team participated — though the players' buses received police escorts.

Soto's boss, Rocky Point Mayor Alejandro Zepeda Munro, met with the Arizona Board of Regents after he took office in January 2010, asking university officials to keep the anti-Mexico rhetoric to a minimum. Since then, the state's universities have gotten out of the warning business. Now, they simply tell students to use common sense wherever they go to Mexico.

ASU encourages students to read the U.S. State Department's Web site about traveling to other countries for spring break, says Karen Moses, director of ASU's Wellness department.

Still, boosters like Soto know they have a lot of work to do to "create the confidence in the parents" of students. It may take time, he says.

But town officials such as Soto and a cabal of developers, promoters, resort operators, and small-time investors and condo owners know they have to focus on getting the message out.

Because the bad news keeps coming.

Last year, a series of troubling news articles only served to ramp up the fear of norteamericanos considering a Rocky Point trip:

• May — Fake checkpoints reportedly were set up for a few nights on Highway 8, the road that leads from the border crossing at Lukeville/Sonoyta to Rocky Point. People manning the checkpoint asked travelers for identification but didn't hurt or rob anyone. It's unclear how long the checkpoints were in operation, but there have been no reports about them since.

• June — Rocky Point Police Chief Erick Landagaray Macias and his bodyguard were ambushed and shot on a major street in town. Both recovered. Macias had been quoted on ABC News about his attempts to reduce corruption on his force.

• June — The same day that Macias was shot, three Rocky Point residents were murdered at a service station in Sonoyta.

• July — An El Mariachi-like shootout between rival gangs outside of Altar, a small town about 100 miles west of Rocky Point, left 21 dead and six wounded.

• August — The bodies of 72 migrants from Central America were found in a ranch house just south of Texas in San Fernando, Mexico. A week later, the lead Mexican investigator in the case and one of his officers were kidnapped and killed.

• October — A U.S. Department of Homeland Security bulletin to local authorities in Arizona stated that cartel leaders had held a business meeting in Rocky Point. DHS admitted later than the info "proved inaccurate."

Rocky Point promoters take pains to note that most of Mexico's really extreme violence, such as the 72-body murder south of Texas, took place far from the beach town. For example, one of the murder capitals of the world, Juárez, adjacent to El Paso, Texas, is more than 400 miles away.

It's as if Americans perceive all of Mexico as the same place, boosters say, arguing that it wouldn't be logical to avoid a trip to Scottsdale because of murders in Oakland, California, or to consider Tucson "unsafe" because of the January 8 shootings of Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and 18 other people.

Yet much closer to home is Nogales, Mexico, about 250 miles north of Rocky Point, and about 112 miles east of the Lukeville port of entry. The city of about 220,000 used to be teeming with tourists shopping for pharmaceuticals and knickknacks, and the bars were packed on weekends with young Arizonans. No more. On a trip there in December, typically a peak time for American shoppers, we found it nearly devoid of gringos.

Nogales saw its crime rate skyrocket last year.

At least 226 people were murdered — a 70 percent increase over the 2009 figures, says a State Department source. One body was found hanging from a street sign, he says.

By contrast, the rate of murders per 100,000 in New Orleans — America's murder capital — was 52 in 2009, about half that of Nogales.

Rocky Point has had about 11 murders per year since 2007, according to figures obtained from the town's police department. Assuming a population of about 50,000, that equates to 22 murders per 100,000 — less than half of New Orleans' rate.

But if it's unfair to compare Rocky Point to Juárez, it's also unfair to compare it to New Orleans, which hosts about 6 million visitors a year. Only a fraction of that number of tourists visit Rocky Point each year.

Strictly by the numbers, Tempe is safer than Rocky Point. Though the city experienced a record year for murders in 2010, with 12, the population of Tempe is nearly four times that of Rocky Point, and it has more yearly visitors. Also, most of the murders — including those of ASU students Kyleigh Sousa and Zachary Marco — were solved by police, and the murderers have been brought to justice.

The nature of crime in Mexico, and especially how law enforcement responds to it, disturbs American sensibilities. Nationally, only about 2 percent of cartel suspects arrested are brought to trial, according to a State Department cable published on Wikileaks in December.

Mexican state police handle the investigations of crimes, not such local authorities as Rocky Point police. No arrests have been made in the August murder at the Malecon, the fatal shooting of a Rocky Point taxi driver in January of this year, or even the shooting of the former Rocky Point police chief.

Lazaro Hernandez, Rocky Point's new director of public safety, tells New Times that the investigation is ongoing.

"Only the ex-director knows what happened, and he's not saying," Hernandez says, seated behind a desk in his small office, a picture of his boss, the mayor, behind him. "He recovered and went back home."

Without a trace of irony he adds, "Maybe it was a jealous husband."

He says he's not concerned for his own safety and walks around town with his children. His mission is to make sure Rocky Point remains a safe destination for tourists, he says.

Any American who's scared to come to Rocky Point is loco, he says with a chuckle.

Only two Americans have died in Rocky Point in the past couple of years, he says — a motorcyclist who crashed after popping a wheelie, and a young woman who broke her neck in a ATV crash.

Local, state, and federal police provide a strong presence in town, and his department has received new vehicles and equipment in the past year to help keep order, he says.

Military forces also can be seen around town. A checkpoint manned by armed, fatigues-wearing soldiers, some in masks, greeted visitors arriving in Rocky Point from Highway 8 in February (though not in December).

Fausto Soto, the mayor's spokesman, says the Mexican Marines go where they feel they're needed, and right now, that obviously includes Rocky Point.

New Times also spotted the Marines driving around town in Humvees equipped with belt-fed machine guns and stationed at the new airport near the Mayan Palace.

According to Charles Bowden, author of a new book about Juárez called Murder City, Mexico's military is the last hope for fighting drug gangs. But, as he notes, "Mexico has never created a police unit that did not join the traffickers. Or die."

Geography helps protect Rocky Point from the worst smuggling-related crime.

That's obvious by checking a map: You don't need to travel through Rocky Point coming north from either Baja California or the mainland. No major smuggling routes through Rocky Point exist to fight over. Highway 8 and the town of Sonoyta, however, probably are used occasionally by the drug gangs.

Cartel members certainly can be found throughout the state of Sonora, including in the Rocky Point area, says Ramona Sanchez, spokeswoman for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency in Phoenix. The Sinaloan cartel, the Zetas, and the others "are still very much fighting for the lucrative smuggling routes and practice intimidation against the authorities. In Rocky Point, we haven't seen the flare-up. That has been elsewhere," she says.

If Rocky Point, Sonoyta, or Highway 8 began to experience a drastic uptick in cartel activity and violence, the DEA would work with the State Department to get the message out to the public, Sanchez says.

So far, the cartels and rip-off crews don't appear to be targeting Americans, U.S. authorities say.

"But with a higher murder rate, you are more likely to get caught in the crossfire," says the State Department source quoted earlier.

Rocky Point has been relatively peaceful, though "I don't want to say it's a bed of roses," the official says. "If, during the daytime, you're staying to the tourist areas, I think you're safe. Make sure people know where you're going and when you're getting back. Be very vigilant, and I highly recommend people to not come alone."

As mentioned, New Times didn't always follow such rules on the two trips taken for this article. And, from that experience, Rocky Point seems to be a Mexican tourist location where locals kindly offer directions (with no danger of decapitation).

Hostak, owner of Al Capone's Pizza, says he hasn't had a single safety problem in the four years he's lived in Rocky Point. Business-wise, though, he worries whether he'll survive another year or two at the current dismal rate that tourists are arriving. Downstairs, in the bar, only a few patrons are present on a Saturday afternoon.

"It just sucks, seeing a beautiful area like this not get used," he says. "It's sad that people live their lives in fear."

At the 130-unit Sonoran Sky resort, most condo units were going unused this winter. Scottsdale resident Jamie, who didn't want her last name used, was among five people hanging out at the Sky's Tiki beach bar, her teenage daughter and mother among them. They own a condo at the Sky and come to Rocky Point "six months out of the year," she says.

She's had a few tequilas, enjoying herself despite the scarcity of other guests.

"I left my husband at home this time," she says. "We drove down with no problem."

Predictably, most Rocky Point vacationers told New Times they don't feel threatened or unsafe coming to Mexico. But they think about the risk.

"Would I feel better if I had a gun in the RV? Yes," says Steve Phillips, the camper from Oregon.

Eva Partel of Vernon, British Columbia, has been coming down to the Mayan Palace for the past three years with her husband, Bill Lim. She's been traveling to Mexico for "years and years," often to Acapulco or Cancún. Rocky Point, an "absolutely gorgeous place," is closer.

"We drove down in four days," says the white-haired senior citizen, holding a novel as she reclines in a lounge chair. She and Lim were the only people poolside. "The first time we went to Rocky Point, my daughter-in-law said, 'You can't do that!'"

She doesn't believe the area is dangerous, but "I know that you have to be careful."

With family in Phoenix, Sigmar Willnauer of Mannheim, Germany, decided to visit Rocky Point for the first time in February with his 7-year-old daughter. He researched the crime situation and even phoned local police before coming, he says. After a few relaxing days on Sandy Beach, he was headed to the Grand Canyon.

On the other side of town, in Las Conchas, the scene at the CEDO oceanographic institute was utterly peaceful. Several Tucson middle-school students and their chaperones were lodged on the institute's second floor, where they were staying for a few days to learn about life in the Sea of Cortez and have fun.

Lisa Foxx, dressed in a black tank top and shorts, points out her 11-year-old daughter on the beach below as she talks with us in the building's courtyard. This summer, she says, her daughter will be coming to the CEDO facility without her — and she's not worried.

"I'll only be jealous," the Tucson mom says with a smile. "I can't say this year I'm anymore nervous — we've been doing this for five years."

Truly, on a such a nice day at the beach, it's difficult to imagine the place suddenly erupting in violence.

And if a visitor does feel a tingle of fear, it's probably nothing a cerveza can't help.

As Americans mull their vacation options, people who live and work in Rocky Point grow more worried about their future. This being Mexico, the difference between rich and poor always has been dramatic. Now unemployment is soaring as cash-strapped businesses close their doors or scale back operations.

Las Palomas, one of the largest high-rise condo towers on Sandy Beach, recently laid off hundreds of workers. Many were unpaid for their last three months of work, says Marco Leon, who works the front desk at the Sonoran Sky. Many of the laid-off employees are his friends.

Some managed to find jobs at restaurants in Old Port. Others moved out of town.

"They used to have one apartment each," Leon says. "Now, it's four people in one apartment."

Israel Garcia, a seafood vendor at the Malecon, says, "People are desperate from the bad economy."

He claims U.S. cities and vacation spots competing for tourists pump out "malicious propaganda" to make Rocky Point and other Mexican destinations look bad.

"If the people of Phoenix say that it is dangerous out here, tell them it is more violent there," he says.

Jose Chavez Ortiz, an 82-year-old resident who lives in a tiny barrio house he built 40 years ago, puts it more bluntly: Son bien miedosos, which translates roughly to "pussies."

His younger relative, Lupe, and her 1-year-old son live with him. She's blind from diabetes and can't get decent medical care, Ortiz says. He has two daughters in the United States, but they don't send him money because they're broke, too, he complains.

"It isn't getting better," he says.

Charitable help from Americans has been reduced in the past couple of years, according to religious organizations that bring good Samaritans to Rocky Point to build homes or help with medical clinics.

One Mission, which owns an RV park on the town's main drag for its charity work, had 1,700 people sign up for home-building last year. Only 1,050 made the trip, says Jason Law, the mission's founder. One house can be built for each 20 people who contribute, which means that, theoretically, 35 fewer homes for the poor were constructed.

People usually call about a week before planned trips and say their moms talked them out of going, or that they saw something on the news that caused them to reconsider, Law says.

A mural hanging in a conference room at the new aeropuerto just north of the Mayan Palace resort displays the history of aviation in Rocky Point. On the left is Al Capone's buddy's airport (an area now covered with houses). The middle section depicts a more modern facility, also now defunct. And to the right is the new Mar de Cortes International Airport, built by GrupoVidanta and opened in November 2009.

Rocky Point officials hope the airport, which can handle 737- and 757-size jets, eventually will usher in a new era for the region — one in which Americans and Canadians will arrive in style, as they have in Cancún and Puerto Vallarta.

The thatched-roof guard shack at the exit off Highway 37 to Caborca gives a quaint first impression of the airport, but the facility is actually international, accepting small planes from Canada and the United States,and larger, charter flights from elsewhere in Mexico. Regular service with 737s between Rocky Point and Juárez is scheduled to begin in mid-April. For now, the airport's temporary terminal doesn't seem to have so much as a scuff or speck of dirt inside.

Continental Airlines is considering flights to Rocky Point from Los Angeles, says the airport's director general, Fernando Antillon. The airport also has been encouraging American Airlines to begin service from Dallas.

In addition, Phoenix is considered a potentially important hub to attract people from Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and states directly north of Arizona, Antillon says. Officials hope to see some U.S. airlines using Mar de Cortes by the end of this year.

The price range would probably be in the $100 to $200 range for short hops from American cities, says Alonso Dominguez, an airport administrator.

"It would be cheaper to fly to Rocky Point than Cabo or other Mexican destinations," he says.

The fly-in service would have the advantage of alleviating the fears of people from Arizona and other nearby locales; many would-be tourists worry about their safety during the drive from Sonoyta to Rocky Point.

But it's clear that airline service to Rocky Point would be no replacement for thousands of Arizonans simply driving down. Traditionally, 80 percent of Rocky Point tourists are American, and 80 percent of those are from Arizona.

Looking to the long-term future, Rocky Point boosters talk about a cruise ship possibly sailing out of Old Port. Tourists could drive or fly to Rocky Point, then cruise around the Mexican Riveria. The idea is clearly a fantasy right now: In January, two huge cruise ships pulled out of the Port of Angeles, ending service to Mexico because of a lack of demand.

On a smaller scale, Rocky Point has tried to build up a semblance of sports tourism, hosting golf tournaments at the Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course at the Mayan Palace and bringing in a new baseball team, the Rocky Point Tiburones (Sharks), expected to throw their first pitch at the town's baseball stadium next month.

One area that really has paid off is the domestic marketing and advertising done in Mexico. Easter week, for example, which most Mexicans have off from work, is booked solid in Rocky Point.

The town in July and August, when heat-loving Mexicans prefer to visit, according to locals, has been packed.

Still, promoters prefer to draw Americans and their fat wallets.

Rocky Point business owners chipped in $1 million of a $2.5 million project to expand the Lukeville port of entry from three northbound lanes to five. The project is expected to be finished by April 15.

If the violence calms down, or at least doesn't increase much, they pray that the past three years will become merely a memory for Rocky Point.

Update:Bad headlines had been rare for a couple of years. Tourism went up. Then Apocalypse Now came to Sandy Beach in December 2013. As frightened tourists watched, a military helicopter fired into a Sandy Beach condo suspected to be a cartel hideout. The federal operation also involved ground troops. Six suspects were killed, including one top lieutenant with the Sinaloan cartel. Yet the remaining suspects were able to flee with the lieutenant's body despite the military operation. How the suspects got out of Rocky Point, which is sort of at land's end with few roads leading out, remains a mystery. As with the violence covered in our 2011 article, though, it's virtually all Mexican-on-Mexican. Attacks on Americans remain rare. Thousands of Arizonans still make the trip each year. If a college student or family has been kidnapped or killed in the last few years, no news outlet has covered it. Buena suerte.