Max Erwin

Audio By Carbonatix

In January, a 23-year-old woman sat in Phoenix Municipal Court listening to a prosecutor lay out the evidence against her. On the night of her arrest, she was scantily dressed, the prosecutor told the judge. She also had condoms in her purse and got into a car with a man.

In Phoenix, that was enough to charge her with a crime.

“Given the way the defendant was dressed, as well as a statement as to a date, and her getting in the vehicle with this witness – there is evidence of manifesting prostitution,” a prosecutor told Municipal Court Judge Alex Navidad.

Or, more specifically, “manifesting an intent to commit or solicit an act of prostitution.” An obscure city ordinance in Phoenix makes this act a crime with a mandatory sentence of at least 15 days in jail.

The woman, whose name Phoenix New Times is withholding to protect her privacy, is one of more than 450 people in Phoenix who have been charged with manifestation of prostitution over the past eight years. The ordinance, which has been called unconstitutional by the ACLU of Arizona, allows the act of flagging down a car or wearing provocative clothing to be used as grounds to cite someone.

In 2014, the city’s prosecution of Monica Jones under the ordinance drew national outcry. Civil rights organizations condemned the arrest of Jones, a transgender activist and social work student. Even celebrities spoke out against the city’s use of the law.

But Phoenix has not stopped using the ordinance, according to data obtained by New Times.

A review of the data showed that hundreds of people – including 90 in 2022 – have been charged with manifesting prostitution since Jones’ case. Over the last two years, the majority of those charged were Black.

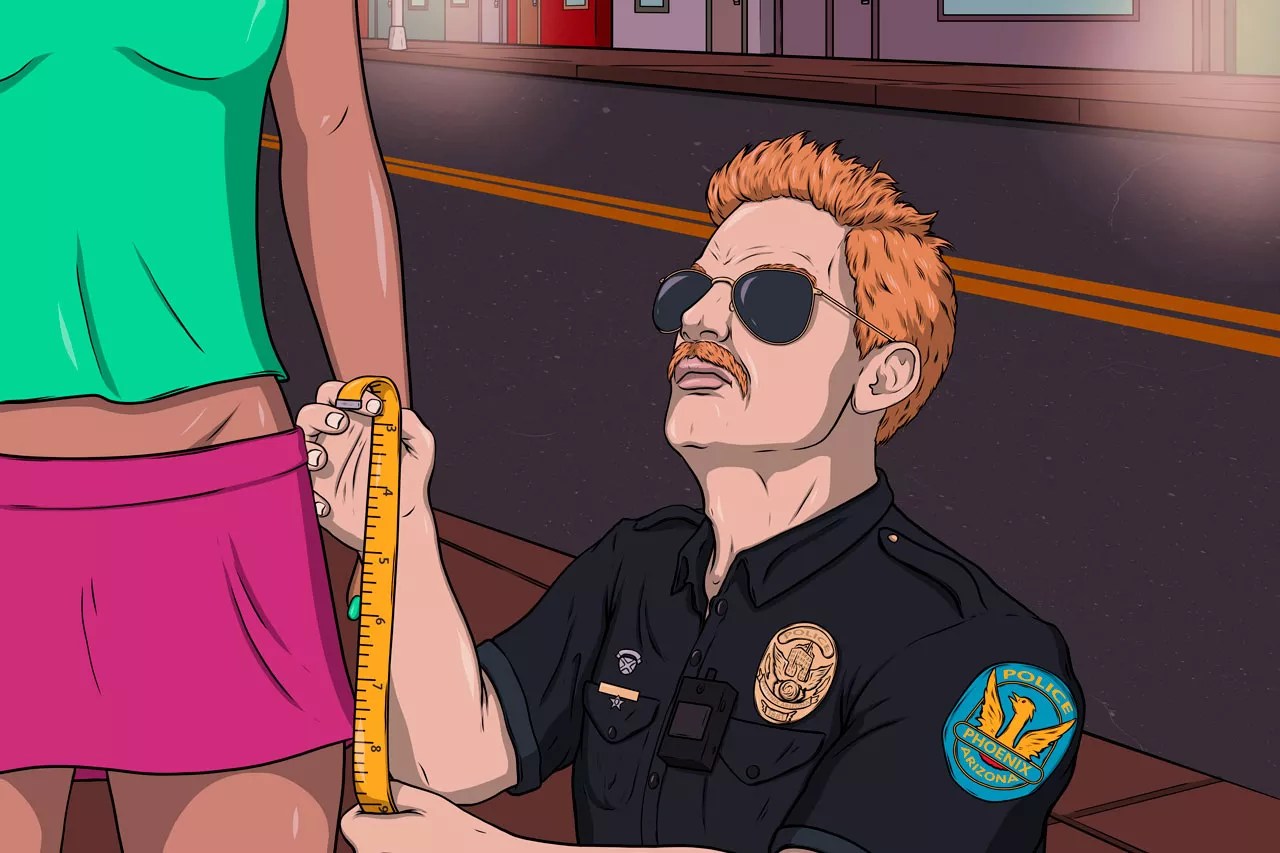

The January court hearing is one example of how prosecutors use clothing to support manifestation of prostitution charges. In multiple Phoenix police reports obtained by New Times, officers wrote down “dressed to attract attention” as one reason they believed people were manifesting prostitution. “Photographs were taken for this incident to document [the woman’s] attire,” an officer wrote in a February report.

An attorney who has represented people charged with manifesting prostitution offered a blunt assessment of the city prosecutions in an interview: “You’re being prosecuted because of what you’re wearing.”

Phoenix City Prosecutor Bob Smith declined to address questions about the ordinance. But Ashley Patton, the city’s deputy communications director, provided a statement defending the prosecutions.

“The City of Phoenix prosecutor’s office reviews all cases submitted to them from the Phoenix Police Department,” Patton wrote. “A prosecutor has a duty to review and evaluate all relevant, admissible, incriminating and exculpatory evidence in the pursuit of justice, a duty they have honored both prior to and since 2014.”

At the beginning of the hearing in January, Navidad voiced concerns that the police report detailing the September 2022 arrest didn’t have enough substance. Once the prosecutor finished speaking, though, the judge turned to the woman, seemingly satisfied.

“Would you agree that all that’s true? Is that what you were doing there?” he asked her.

“I guess I have to say yes?” the woman responded. There was a pause. She continued: “Yes.”

Her sentence? Thirty days in county jail.

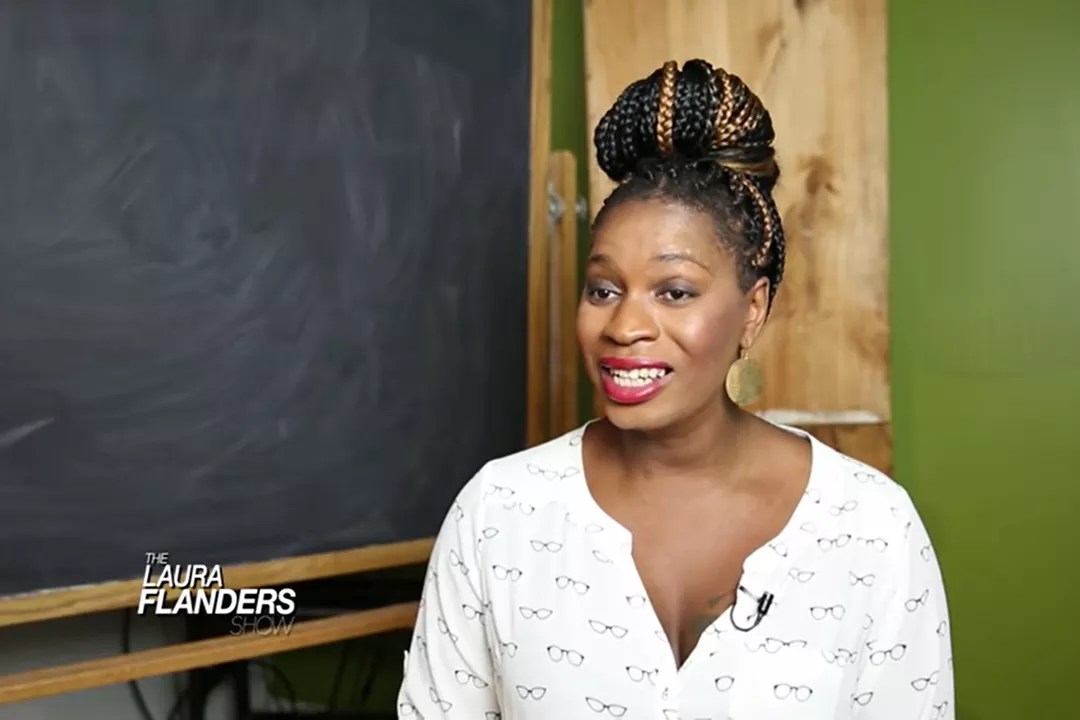

Monica Jones in a 2015 interview. Her 2014 arrest in Phoenix gained national attention.

The Laura Flanders Show

An unconstitutionally vague law?

What exactly is “manifesting the intent to commit or solicit prostitution”? On this question, Phoenix city code is vague. The law lists several circumstances that can factor into such a determination. If a person “repeatedly beckons to, stops, attempts to stop or engage passerby in conversation” or “repeatedly stops or attempts to stop motor vehicle operators by hailing, waving, or any other bodily gesture,” they could be under suspicion.

Also, if someone “inquires whether a patron … is a police officer” or “searches for articles that would identify a police officer,” this, again, could be evidence of manifestation of prostitution, according to city code.

Much of what is contained in the law – asking questions or approaching motorists in a public place, for instance – is “protected First Amendment activity,” said K.M. Bell, a staff attorney at the ACLU of Arizona. “It is very concerning just the way that statute was written.”

In an August 2014 court pleading, ACLU attorneys outlined other problems they had with the crime’s vague definition. “Is it impermissible to flirt with someone on the street or in a car? Hail a cab? Wear a ‘tight fitting black dress?'” attorneys wrote.

“It is difficult to imagine how anyone on a Phoenix street would know if he or she were violating the code,” they argued. The law clearly violated the constitution, the attorneys noted in their defense of Jones.

She was arrested for manifestation of prostitution on May 17, 2013 after accepting a ride home from an undercover Phoenix police officer whom she had met at a bar. A few minutes after getting in the car, a police vehicle pulled up, and she realized she had been caught up in an anti-prostitution sting.

That night, Jones was wearing a “black, tight-fitting dress,” the Phoenix police officer testified at trial. She was in an area known to have prostitution activity, he claimed, never mind that the arrest occurred near where Jones lived. A municipal court judge sentenced her to a month in jail.

Jones’ arrest drew widespread outcry. Across the country, civil rights advocates called the arrest an example of the dangers of “walking while trans.” Laverne Cox, the trans actress and star of “Orange Is the New Black,” came to her defense.

“The goal should be overturning laws like this and really understanding the kind of environment that we all are creating as citizens of this country for trans women, particularly trans women of color,” Cox said in 2014.

Ultimately, the charges against Jones were dismissed, which ended an appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court before it had a chance to review the law.

Now, Jones is based in Tucson and serves as executive director of Outlaw Project, a nonprofit that provides housing support and other aid to trans women of color and sex workers. Lately, the Outlaw Project has been working on building tiny homes and creating a community space. Jones said that she sees her work as an answer to the way trans women and sex workers are pushed out of communities and denied access to housing – sometimes as a result of measures such as the manifesting prostitution ordinance in Phoenix.

Jones wasn’t surprised that the city is still arresting and prosecuting people nearly a decade after her case. “They just waited till everything died down to pick it back up,” she said. “It doesn’t surprise me. This is what our government does.”

Phoenix police have issued more than 450 manifesting prostitution citations since 2014.

Matt Hennie

‘A clear racial disparity’

The typical manifestation case in Phoenix follows a pattern. Most people are cited at night in the area of 27th Avenue and Indian School Road, according to dozens of recent citations obtained by New Times. The area, often colloquially called “the track,” is known as a hub for sex work. Some people are ticketed and given a court date, while others are arrested.

More than half – 53% – of the 122 people charged in manifestation cases from January 2022 to February 2023 were Black, according to data from the Phoenix city prosecutor. Yet Black people make up just 7% of the city’s population. Another 44% of those charged were listed as “white,” though the data did not indicate whether a person was Hispanic or Latino.

“There’s a clear racial disparity there,” Bell said, calling the numbers “incredibly disproportionate.”

Data from the city’s prostitution diversion program – which is available for people facing a range of prostitution charges – also shows significant racial disparities in who is getting cited for prostitution crimes. From May 2019 to November 2021, 38.9% of program participants were Black, according to a program report obtained by New Times. Another 15.3% were Hispanic or Latino, and just 16.7% were white.

“We cannot speculate on demographic data,” Patton, the city of Phoenix spokesperson, said in response to questions about the disparities.

The data supports claims by activists that vague laws such as manifestation often are used disproportionately against people of color. “Black and brown bodies are being targeted because of the neighborhoods that this ordinance is being enforced in,” Jones said.

The enforcement around 27th Avenue is a good example of this, she explained.

“That’s a low-income area,” Jones said. “Yes, there’s street-based sex work there. But [the law] is criminalizing everybody that’s walking down that street.”

Patton said that the city considers the area “a known location for human traffickers,” and for that reason, it was a focus for Phoenix police’s Human Exploitation and Trafficking Unit. Yet human trafficking cases, which generally are handled by county prosecutors, are distinct from misdemeanor prostitution citations.

Laws like the one in Phoenix, according to critics, also are used by police to target trans women and label them as sex workers simply for walking down the street. “Unfortunately, a lot of transgender women, particularly transgender women of color, are profiled under these laws,” Bell said.

The data on arrests under the ordinance did not track how many trans people were prosecuted in the years since Jones’ arrest. The police reports and citations obtained by New Times also did not include information on whether a person cited was transgender.

And while manifestation charges are harmful for people who might get caught up in the system despite not being involved in sex work, they also can be harmful for sex workers, activists argued.

The first time someone is charged with manifestation of prostitution, they are eligible to have the charge dismissed after they attend the city’s diversion program. But if they don’t make it through the program, the city ordinance mandates a 15-day jail sentence. A second conviction requires 30 days in jail. A third conviction carries 60 days, and any conviction beyond that is a mandatory 180-day sentence.

One woman who has been cited in Phoenix said that the penalties – and lasting record – from such charges made it difficult to build a life outside sex work. She was convicted of the crime of prostitution – a different charge than manifestation of prostitution under city code, but one that carries the same penalties. She spoke on the condition that New Times withhold her name to protect her privacy.

“I’ve struggled with housing,” she said. “Places wouldn’t rent to me because of my background.” While she has a degree and has started to build a successful career, she has encountered roadblocks at work due to the past charges, she said.

The mandatory jail time was harmful, she said, and hardly a good way to help people move on from sex work. “That’s the thing – you’re just putting me back 15 days,” she said. “And when I get out, I’ve got to do it again because it’s the quickest way to make money.”

A jail sentence won’t help move people away from sex work, according to Arlene Mahoney, executive director of the Southwest Recovery Alliance, an organization that advocates for the rights of sex workers.

“If you have to step away from your life for 15 days, it’s going to have a harmful impact. Arresting people for sex work is not going to get them out of sex work,” Mahoney explained.

In February, Mahoney was among a coalition of activists who took to the streets in downtown Phoenix to protest police raids of sex workers ahead of the Super Bowl. Dubious claims about a rise in human trafficking before large sporting events spread by law enforcement often lead to increased arrests of sex workers for low-level prostitution crimes involving consenting adults, the activists argued. “Sex workers don’t need rescue. We need rights,” Mahoney said.

Manifestation arrests did increase in January and February ahead of the Super Bowl in the Valley on Feb. 12. In the two weeks leading up to the big game, 16 citations were issued for manifesting prostitution, compared with an average of about eight citations per month in the 12 months prior.

Officers issued 180 misdemeanor citations to sex workers as part of “Blue Wave 23,” according to a Phoenix police presentation. The sting ahead of the Super Bowl involved 11 local law enforcement agencies. Another 120 citations were issued to “sex buyers,” according to the presentation.

The command post for the operation was located at the Helen Drake Senior Center at 27th and Glendale avenues, Patton said. She emphasized that law enforcement did outreach in the area in the weeks leading up to the Super Bowl. “More than 50 individuals were connected to services as a precursor to enforcement operations in that area,” Patton added.

“Sex workers don’t need rescue. We need rights,” said Arlene Mahoney during a protest in February.

Katya Schwenk

Faith-based diversion program

There is a long history in Phoenix of raids on sex workers. In 2014, the city faced national attention for prostitution stings in which hundreds of sex workers were rounded up and brought to Bethany Bible Church in Uptown to – as one investigation put it at the time – “save their souls.”

The raids occurred under Project ROSE (Reaching Out to the Sexually Exploited), a collaboration between Arizona State University social workers and Phoenix police. It was the brainchild of ASU professor Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, who argued the program provided resources and support to sex workers. Critics raised serious concerns about the program, which appeared to bring people to the church without access to lawyers and pressured them into diversion programs before their first court hearing.

Around the time of Jones’ arrest, Project ROSE was under public scrutiny. The ACLU demanded a trove of records about the program. By the end of 2014, Project ROSE had been quietly retired – in name, at least. “Phoenix police has not participated in Project Rose for nearly a decade,” Patton said in response to questions about the operation.

But people who are convicted of manifestation of prostitution in Phoenix often are forced into a diversion program with a similar ethos as Project ROSE. The city’s current prostitution diversion program is run by Catholic Charities, an organization that advertises its “faith-based roots.”

The program is only available after a person’s first prostitution charge. Completing it is an intensive months-long process. To get the charge dropped, a person must attend 36 hours of classes followed by several weekly classes for 10 weeks. Those sessions include support group classes, life skills classes, counseling and “addictive behavior” therapy sessions, according to a flier for the program. The city pays Catholic Charities around $232,000 annually for the program, according to contract records.

Meanwhile, if you’re convicted of hiring a sex worker, which is called solicitation of prostitution, the diversion program is far less stringent. It mandates a single eight-hour class and $725 fine.

Most people who enter the city’s intensive prostitution diversion program fail to complete it, according to years of monthly reports obtained by New Times. Between May 2019 and November 2021, 122 participants out of 228 failed out of the program, the reports showed.

In 2022, the numbers improved and 65 out of 100 program participants were successful, the reports showed. So far in 2023, 53% of participants have been successful.

But the program’s success rate falls short of the city’s diversion program for people charged with domestic violence offenses. That initiative has a 95% success rate.

Jean Christofferson, a spokesperson for Catholic Charities, declined to comment. But she did provide New Times with a recent flier for the prostitution diversion program, which described it as “a diverse set of programs designed to give those involved in prostitution the help needed to break away from that cycle and rebuild their lives.” The flier claimed that 86% of successful participants were not charged again, citing statistics from the city.

Activists are still critical of the diversion program. “It imposes religious morals onto a person when they were just trying to survive,” Mahoney said.

The woman cited for prostitution in Phoenix said that she also went through the diversion program at one point. She described it as burdensome for many participants, though she also acknowledged that it provided important resources.

“Not everyone has access to get to these classes,” she said. “They might have children, and they’re trying to make a living, whether it’s sex work or not.”

Data from the program obtained by New Times shows that of participants with known incomes, 87% reported making $9,999 or less annually.

City prosecutors declined to discuss the ordinance that critics said is used to target trans and Black people.

City of Phoenix

Laws overturned elsewhere

Manifestation of prostitution has been a crime in Phoenix since at least 1975, according to city council records, and was expanded in the 1990s. There are similar “intent” laws across the country that give police wide discretion to target sex workers. One common crime is “loitering for the purpose of prostitution,” a law that multiple states have on the books.

Anne Gray Fischer, an assistant professor of history at the University of Texas-Dallas, has studied the laws and said they are vague on purpose.

Those laws are “designed to be very broad, so that police can maximize their intervention and power to remove people from the streets for how they look,” she explained.

In some places, such as New York, the laws were passed so that police could more quickly raid an area with prostitution activity.

Elsewhere in the country, there have been efforts to repeal such laws. In 2021, New York repealed its loitering law following a successful campaign by activists that highlighted how police used the ordinance to harass trans people. In 2022, California repealed a similar law. In Florida in 2013, a court struck down a city’s “loitering with intent to commit prostitution” law, finding it unconstitutional.

In Phoenix, though, citations for manifestation of the intent to commit prostitution are continuing to be issued, with little public scrutiny.

In January, after Navidad sentenced the young woman to 30 days in jail, the municipal court judge paused and asked about her next steps. “What are you going to do when you get out of jail?” he asked.

“Go to school or something. I want to do cosmetology school,” she answered.

“Do you have a plan on how you might be able to afford that? Or where you’re going to live?” the judge asked her.

After a moment, a note of irony in her voice, she said, “Nope. We’re going to have to go day by day and figure it out.”