My mother is washing dishes. She’s using a paper napkin she found in the kitchen sink, and a little bit of leftover coffee from a mug on the counter. She scrubs at bits of egg stuck to a fork, sets it next to the saucer she’s just cleaned. Then she grabs the saucer, wets the napkin with the coffee, and washes the saucer again.

“Hey, Duchess!” I call to her from across the kitchen. “What’re you doing?”

“I’m getting all the train books ready,” she replies, looking cross. “She said they were eight coming, the children.”

She moves to the refrigerator, and begins to gather food for the people she imagines are on their way to this house where she has lived for 50 years: a half-empty Tupperware of minestrone, a hard-boiled egg, the bowl of oatmeal she refused to eat this morning. (“It’s too spectator pump,” she had complained, pushing the bowl away.) She piles these things onto the kitchen table, then heads off to her room, probably to dress for her phantom company.

By the time she arrives there, my mother will have forgotten what she wanted. Her 10-year-old Alzheimer’s diagnosis was recently reclassified; she’s now a 6 on the Global Deterioration Scale, a means of measuring the depths of dementia that tops out at 7. The Duchess will arrive at her bedroom, become distracted by something — a lampshade, her framed wedding portrait, my dead father’s key ring — and dressing for imaginary company will be forgotten. These days, for Maria Domenica Clemente Pela, pretty much everything is forgotten.

I don’t follow her to her room. I’ve got a kitchen to clean and a stack of insurance papers to fill out before I take the Duchess to her quarterly oncology appointment later this afternoon. A decade ago, I took my time with things: finished a project only when it was perfectly complete; awoke when I was done sleeping. Today, I’ve learned to take shortcuts. There’s never enough time to do everything, or to do anything especially well.

I am what is politely referred to as a caregiver.

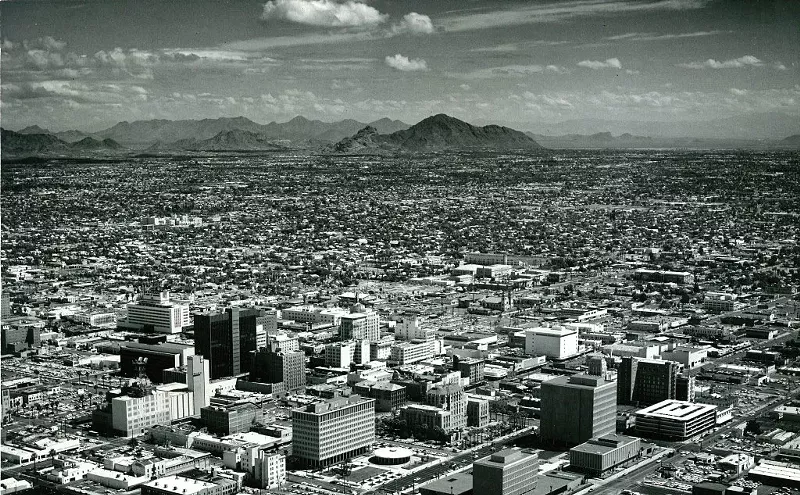

I spend most of my days and some of my nights here at the suburban West Phoenix house where I grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, where my 91-year-old mother and I have been playing a decade-long game ever since she began losing her mind to Alzheimer’s disease: She is the Duchess of Pela, and I am her minion. I awaken her, bathe her, dress her, and feed her, after which she sits in her kitchen, a gentle expression fixed on her face, reading and re-reading the story of her life, a 249-page, handwritten essay she composed a dozen years before she began forgetting who she was and where she lived. Several times a day, she looks up from her journal. “Have you read this?” she implores. “It’s good!”

In the afternoons, the Duchess is restless. Her journal no longer holds her interest; she refuses to play with her little box of paste jewels. She’s anxious to get home to the house in northeastern Ohio where she hasn’t lived since 1942, worried she won’t be able to find it on her own. She paces, maniacally tidying her kitchen, distracted by some puzzling chore she must complete but can’t quite fathom.

I’m distracted today, too. I’ve received a press release announcing that Tempe has joined the Dementia Friendly America initiative. Introduced last summer at the White House Conference on Aging, this yet-unfunded program means to create a “national dementia friendliness,” one city at a time, by training individuals, businesses, and first responders to recognize and respond appropriately to people with memory impairments. Thirty-six towns and cities in Minnesota, where DFA was launched last year, have adopted the initiative’s four-phase roadmap; in March, Tempe became only the sixth city outside Minnesota to join the dementia-friendly fray.

How’s that going to work? I wonder, as my mother ambles into the kitchen carrying three handbags and a toilet plunger, a wilted brassiere wrapped around her wrist. How is an entire city going to learn to deal with old folks who insist that Herbert Hoover is president, people who can’t tell a bra from a bracelet?

The very idea of a dementia-friendly world strikes me as preposterous. I can’t convince the respite care workers I sometimes hire, who are supposedly trained to deal with the memory-impaired, not to tell my mother that her husband died three years ago. She thinks she’s 9, and little girls don’t have husbands. It upsets her to hear otherwise. Some of the medical professionals who look after the Duchess, when told she has Alzheimer’s, speak more loudly, as if volume adds clarity — even though she’s not hearing-impaired. If I can’t get my mother’s own children and grandchildren to take part in her care, how can Tempe expect to sell sensitivity training to a reluctant universe of clerks and bankers and doctors?

“Is this yours?” my mother asks, holding out the toilet plunger.

“Yes,” I lie, taking it from her. “I’ve been looking for it everywhere.”

“Well,” says the Duchess, looking me up and down. “It doesn’t look like it’s going to fit.”

The statistics are bleak. According to last year’s annual report from Alzheimer’s Disease International, the number of people with dementia worldwide has grown to just shy of 47 million. That figure is expected to double by 2030, and to triple 20 years after that. According to Latinos Against Alzheimer’s, the Latino population will see a 255 percent increase in dementias in its communities. For now, one in nine seniors has some form of dementia. Arizona alone will see a 71 percent increase in the number of residents with dementia over the next 10 years.

An ADI policy brief published in 2013 on the global impact of dementia claims that most governments around the world are unprepared for this oncoming health crisis, which will have an impact mostly on low- to middle-income countries with fewer resources to support demented people and their caregivers.

There are other hurdles to a dementia-friendly anything. According to that ADI report, about half of all dementia patients go undiagnosed, in part because most people figure there’s no point in being diagnosed when there’s no cure.

“We’ve got a long road ahead of us,” Jan Dougherty tells me when I call to ask about this Dementia Friendly thing. I know Dougherty in her role as director of family and community services at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix, where my mother is a patient. BAI is partnering with the Tempe project, and Dougherty is the liaison between the two.

“Right now, dementia is where cancer was in the ’60s or HIV was in the ’80s,” Dougherty explains. “People are really just starting to talk about this disease openly. There’s more education on the stupid Zika virus than there is on dementia. But we have to start somewhere.”

Apparently, Dementia Friendly Tempe is as good a place as any. Based on the World Health Organization’s 10-year-old Age-Friendly Cities and Communities program, which has nearly 300 communities in 33 countries, the Dementia Friendly movement has grabbed a toehold in Australia, Canada, the U.K., Germany, and Belgium. India, Singapore, and the U.S. have most recently jumped aboard. The program is designed, according to that press release, “to help communities better understand, embrace, and support residents living with dementia.”

Okay. But how? I watch an animated video on the DFA website in which ethnically diverse line drawings are made happier because everyone they meet knows how to interact with dementia patients. According to the cartoon, DFA will educate local businesspeople about how to support customers with dementia, convince employers to support employees who are caregivers, and teach law enforcement and city service providers how to deal with the demented. DFA is also proposing changes to transportation, public spaces, and emergency response that would allow people with dementia to interact in their community. In some cities, “memory cafes,” where memory-impaired people can gather, have made it onto the must-have list. Businesses will all, according to this plan, one day post a logo on their doors proclaiming they are dementia friendly.

Signage is a big part of the DFA campaign, which right now doesn’t have a deadline or a completion date. Once things get going, Tempe will presumably be covered in printed graphics illustrating how to use a public restroom, and menus with symbols indicating the difference between a turkey sandwich and a hot dog.

The materials on Dementia Friendly America remind me of the early groundwork laid by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, which imposed accessibility requirements like wheelchair ramps and Braille signage in public places, and led to a more welcoming approach to differently abled people. I wonder: Can the DFA initiative eventually have the same impact as the ADA, which is now a law?

“That’s the idea,” Tempe Mayor Mark Mitchell tells me when I call to pick his brain. “We’re in the beginning stages. So far we’ve had a kickoff meeting, and we’re assessing the city staff to identify its strengths. Then we’ll reach out to the faith community and legal professionals.”

“To ask priests and rabbis if they want to learn more about dementia?” I ask. “To request pro bono representation for Alzheimer’s patients?” I apologize to Mitchell for being slow on the uptake. But even with the help of the little cartoon, I’m still struggling to grasp how Tempe will implement a program whose four phases include vague bullet points like “Form a community engagement sub-team” and “Develop an organized process flow and timeline,” and wraps up with “Create and implement a community action plan.”

In Boston, a city roughly four times the size of Tempe, a pair of full-time salaried positions was created to advance this sort of dementia-friendly public education. Will Tempe do something like that?

“We don’t have the funding for that,” admits Mitchell, whose own mother has Alzheimer’s and lives in an assisted-living facility. “But we’re going to apply for grants, and put together a stakeholder group to oversee fundraising.”

In the meantime, Mitchell plans to begin networking with Tempe’s neighborhood associations, which he says are the best in the state, to get the word out about dementia. His grassroots strategy smacks of boosterism; how can people whose job it is to host home tours and throw pot lucks launch a dementia education initiative?

“One person at a time,” Mitchell replies. “Fifteen hundred people in my community have dementia, and I need to get the city educated on how to help them.”

Okay. But would Mitchell have climbed aboard the dementia-friendly bus, I ask, if his own mother didn’t have Alzheimer’s?

“I don’t know,” he answers. “Would you be writing a newspaper article about it if your mother didn’t have that same disease?”

Touché, Mayor Mitchell.

The Duchess and I are seated in the waiting room of her new general practitioner’s office, waiting for the results of her annual tuberculosis test. She is stressed out about getting home late for supper and being grounded by her father, who died in 1958, and I am entertaining myself by counting the number of times she tells me she hasn’t any pancakes in her purse (17 times so far, and she’s not carrying a purse today).

The woman seated across from us smiles at me. “My mother had dementia, too,” she quietly confides. I return her smile and think to myself, Okay, I’m about to have this conversation again.

“I took care of her for two years before we had to put her in a home,” she is saying, and I’m thinking, Two years? Really? Two.

“How difficult that must have been for you,” I say. “And how does she like it there?”’

“Oh, she died three weeks later,” the woman replies, after which the Duchess and I excuse ourselves and move to the other side of the waiting room.

A little while later, we’re taken to an examination room by a nice medical assistant named Juanita, who talks baby-talk to my ancient mom.

“Will you get up on the scale so we can weigh you, please, Miss Mary?” Juanita asks with a big pout, her words all syrupy, rounded vowels. The Duchess shoots me a look that clearly says, Get this person away from me! and I look back at her with an expression that replies, Oh, right, you’re the parent I inherited my crummy attitude from!

“My mother has late-stage Alzheimer’s disease,” I explain to Juanita as I pantomime how to get on and off the scale. “Sometimes showing works better than telling.”

Juanita smiles at me and turns to the Duchess. “Have any of your medications changed since last time you were here, Miss Mary?” My mother begins a long, disjointed explanation of why she chose to wear this particular pantsuit, indicating the sundress I’d put on her that morning. Juanita turns to me.

“Is she always like this?”

“She has late-stage Alzheimer’s,” I remind her, handing over an updated list of medicines. My mother is still trying to tell her pantsuit story when the doctor joins us. Rather than talk to my mother as if she were a precocious toddler, he ignores her entirely, speaking only to me. It turns out Her Majesty does not have tuberculosis.

When we get home, I put the Duchess down for a nap and then I call Olivia Mastry, the executive lead for Dementia Friendly America. I want to ask her, “How come everyone gets to have a mother who dies except me?” I’d like to say, “How come health-care workers all call my mother Miss Mary, as if she were a plantation owner in antebellum Atlanta?” Instead, I ask how much importance DFA plans to place on training medical professionals to deal with demented people.

Plenty, she promises. “We have tools and resources that guide each sector of the community, and there’s a real emphasis on physicians and their staffs. It’s not all clergy members and clerks. We’re still defining what dementia-proficient means for medical workers, and once we do, everyone from doctors on down will be held to a standard.”

Really? Training the entire medical community seems like a pretty tall order. I call Dr. Pierre Tariot, my mother’s doctor at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, and ask him if this seems doable to him.

“I’d like for it to be,” says Tariot, a geriatric psychiatrist and clinical researcher who’s spent his career studying people with brain disease. “It’s going to take a long time. When you’re talking about social re-engineering, you have to look at who needs to be educated first, and I agree with you that it’s general practitioners and hospital personnel who need to be dementia-capable right now. For the most part, they are not. Maybe attorneys next, and then police and firefighters, for sure. And we really need to do a better job for the people who are actually providing care to dementia patients.”

While Dr. Tariot and I are saying our goodbyes, the respite care worker arrives for her twice-weekly shift. “Hellooooooo Miss Mary!” I hear her cooing in a voice typically reserved for really cute puppies. “Remember me?”

Maybe, I think to myself, I’ll die in my sleep tonight and I won’t have to deal with any of this anymore.

It’s Monday, my day off from the Duchess. I’m doing my public speaking shtick, addressing a group of new caregivers at a local library, something I do sometimes as a member of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Association’s Regional Leadership Council. After I shuttle through a PowerPoint presentation about dementia titled “Know the Ten Signs,” a woman in the audience raises her hand and asks me what she can expect from her new life as her father’s in-home caregiver.

I want to tell her: You will fight with insurance companies over nickels and dimes. You will apply again and again for assistance programs whose applications are designed to drive you mad with minutiae, only to be denied. Your siblings and their spouses and their grown children will refuse to help you. They won’t call or visit or help pay the bills. Your extended family will “choose sides,” probably with the people who don’t call or visit or help with the bills. Your friends will try to convince you that “placing” your parent is a better choice. When your parent runs out of money, you’ll empty your savings account, your husband’s saving account, and your retirement fund in order to keep up with your parent’s bills. You and your husband will both take second jobs to make ends meet. You’ll cash your IRA and sell your investment property and your grandmother’s heirloom gold bracelet because Medicare has decided it’s no longer going to pay for the pills your parent needs to get through the day. You will rue the day you ever believed things like “Family is everything” and “Honor thy mother and father.” You will exchange cleaning your house and going on vacation for changing diapers and bathing a wrinkled body and doing battle with a revolving door of caregivers who are there to help but usually don’t. All of these things will combine to break your heart, wear you out, and make an already unpleasant job all the more difficult.

I don’t say any of these things. Instead, I smile and say, “Call the Area Agency on Aging; they offer advice on how to find a good care agency.” I leave out the part about how most of those agencies charge $40 an hour for unskilled labor, and who can afford that? I tell a cute anecdote about Sherry, the marvelous caregiver I hired after my dad died and I needed help with Mom that my family refused to give, skipping the bit about the monsters I employed before marvelous Sherry came along. I hear myself saying, “Support groups can help!” and “A hospice palliative account is a good idea!” and wishing I believed these things more myself.

On my way home, I telephone Tom Egan, president of the Foundation for Senior Living, whose staff is working with the Dementia Friendly Tempe folks. “How can you make the world dementia-friendly when, right now, so few people understand the basics about dementia?” I ask.

“Think about autism,” Egan answers. “Thirty years ago, we knew almost nothing about how to accommodate people who had it. Forty years ago, we had very different views of domestic violence. Today we’ve got shelters for battered women, and most people know someone with autism and have been taught how to interact with them. Twenty years from now, the dementia-friendly model will be second nature, something we all know how to navigate.”

In the meantime, caregivers do that navigating without a proper compass, faking our way through nursemaid jobs we’re unqualified for. Sixty percent of caregivers, Egan reminds me, are family members working for free. “There is literally billions of dollars’ worth of unpaid services being given by family members,” he says. “We don’t have enough services, and a long wait list for those that we do have.”

Hey, no kidding. Twice a year, I telephone all the local elder-care agencies I know of to inquire whether they’re offering any new programs that benefit old, demented women and their exhausted, embittered caregivers. The news, usually delivered by a courteous and helpful administrator, is always the same: Nope!

The Foundation for Senior Living only takes referrals for respite care from the Area Agency on Aging, which can’t offer services to people who are already receiving assistance from the Arizona Long Term Care System, which I’m glad to say my mother does. The same goes for the Senior Adult Independent Living agency and the Veterans Administration, which are doing their best not to duplicate services. Just last week, the very pleasant woman who answered the phone at Hospice of the Valley told me all she could offer was to send someone to visit my mother if she was sick.

“Hey, Duchess, are you sick?” I’d asked my mom.

“I have time for five steamed radishes,” she’d replied, holding up the hair scrunchie she’d been playing with for the past three hours.

“No, she’s not sick,” I said into the phone before hanging up. Then, just for the hell of it, I called all five of the health-insurance agencies that currently represent my mother, to ask for help. No one laughed when I explained that I was calling to see if there was anything new I should know about, maybe a free adult diaper service or a just-launched, state-funded respite-care program or, you know, perhaps someone had found a giant box of money lying around that they wanted to give to an old lady with Alzheimer’s so she could get her dishwasher repaired and pay off her attorney bills.

One of the insurance agents gave me the number for the Arizona Caregiver Coalition, where a nice woman named Cathy listened politely to my request and then asked if I’d considered asking my family to help care for our mother.

“Gosh, I never thought of that before,” I lied, because I didn’t have the heart to tell her that I’d implored my family for years to help me care for our parents, but they were “too busy” and opted instead to “visit” my parents for an hour or two, because visiting and caregiving are presumably the same thing.

I call Jan Dougherty again. I don’t tell her that I worry that I’ll never stop being angry. “I’m concerned,” I say instead, “that I’ll one day add Dementia Friendly Tempe to my list of agencies that have pretty much nothing to offer me.”

Dougherty gets it. “The purpose of a dementia-friendly community is that no single caregiver is doing all the work himself,” she assures me, then reminds me that DFA’s online support materials include lists of caregiver agencies and support groups. I tell her I’ve called them all, and then we talk about money for awhile. She tells me how, for now, the Dementia Friendly Tempe project is self-funded, but she’s planning to apply for a $50,000 grant; I tell her about how the last time I asked my family for help with my mother’s bills, I got an e-mail from my sister’s latest husband suggesting I sell my house if I needed money.

Dougherty sighs, and I chuckle and change the subject. Will these dementia-friendly cities eventually catch on, I ask, merging into one big country full of people who know how to talk to people who think it’s 1973?

“That’s what we’re aiming for,” she says. “Our country adjusted to and created meaningful access to people with physical disabilities, and now we need to adjust our thinking for cognitive disabilities.”

The next day, I attend the council meeting of the Senior Lawyers Division, where the subject is dementia and what to do about it. Mayor Mitchell gives the welcoming remarks; his father, former congressman Harry Mitchell, delivers a moving speech about watching his wife, Marianne, slip away from him. At the end of the day, Dougherty gives a helpful presentation about Dementia Friendly Tempe, during which the fellow sitting next to me, whose nametag tells me he’s George, leans over and whispers, “It’ll never work.”

“I don’t know,” I tell George afterward. “These people are working pretty hard. And I like the idea that someone is out there training people how to speak to my mother and other people like her.”

George rolls his eyes. “I stopped waiting for anyone to come help me take care of my dad. I look at it this way: I got two hands, I can do the job myself. A shitty diaper isn’t gonna kill me. Neither is giving my dad a shower. I just tell myself to look at it as a privilege.”

While I wait for the valet to fetch my car, I wonder whether people can change the way they think about things. I haven’t once thought of caring for my demented mother as anything but a necessity, a pain in the ass, something done in return for the devotion she showed in raising me. There hasn’t been a day, these past 10 years, when I awoke with the thought, “Oh, hooray! I get to go change my mother’s diapers today!” Could I learn to see caregiving as some kind of honor? Could an entire community learn to think of all memory-impaired people as somehow their responsibility?

“Here you go, Duchess. Dinner.”

My mother considers the food I’ve placed in front of her. “What can I do?”

“You can eat it. I made it for you.”

“Oh. What is it?”

“Cream of potato,” I reply. “Ham and Swiss on rye.”

“Where does it go?”

“In your mouth.”

“Your mouth?”

“No. Your mouth. I made it for you to eat.”

“Oh. I didn’t know that. Nobody told me.”

“Okay. Eat, please.”

“Eat what?”

“This sandwich. This soup.”

The Duchess is getting angry. “What’s soup?”

“The stuff in the bowl. I made it for you to eat.”

“I didn’t know. No one told me.”

And so it goes, for another 20 minutes. My mother is having one of her more lucid days, which means every act is accompanied by a maddening conversation about nothing at all, a conversation that doubles back on itself and never gets anywhere. By nightfall, she will have exhausted herself, which means she won’t remember what a toilet is for or how to brush her teeth, and will argue with me about swallowing her bedtime pills.

I’m still thinking about George, and about caregiving as a privilege. As my mom whines about potato soup, I am itemizing the good stuff: the attentive staff at Banner Alzheimer’s, the pair of cousins who routinely call and e-mail to ask “How’s Aunt Mary? How’re you?”, the recently retired friend who offered weekly respite care, the friend who visits with her 1-year-old daughter each week so the Duchess can have a baby in her life again.

Right around the time my mother dumps her bowl of soup on the floor and begins crying, I give up on my list. Gratitude eludes me. I remember too keenly the vacation home I used to visit, the family I used to believe in, the writing career I once had time to nurture. There are no city-funded programs designed to return those things to me. I can see how hard people like Jan Dougherty and Mayor Mitchell are working to fix things for people with screwed-up memories. But when your days are spent asking people not to talk down to your mother, pleading for assistance from elder-care agencies, and mopping up potato soup, it’s hard to believe in a dementia-friendly world.