In July and August, two transformer fires cut the $2 billion facility's output by more than half.

At roughly the same time, two new air-quality issues have arisen, spurring Maricopa County officials to research if the plant violated air-pollution standards. Last year, the county imposed a record $1.5 million fine on Solana for air-quality violations.

These problems follow a host of others that the facility, built by Abengoa of Spain, has suffered since starting operations in 2014.

The plant's parent company, a subsidiary of Abengoa called Atlantica Yield, downplayed the issues, and a company representative said that better times are likely ahead.

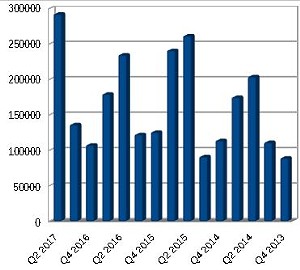

This chart, based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, shows how quarterly performance at Solana was doing better through June. In July and August, transformer fires cut production drastically.

Ray Stern

Solana, which is Spanish for a sunlit spot, generates electricity by focusing 900,000 parabolic mirrors on tubes containing a super-heated fluid that gets pumped to two steam turbines. Because the fluid stays hot for hours after the sun goes down, concentrated solar plants like Solana continue to provide electricity when photovoltaic panels — like those found on many Phoenix rooftops — stop being productive.

But concentrated solar power is expensive compared to photovoltaic solar and natural gas. And the plants don't always work as advertised.

Solana should be producing more than 900,000 megawatt hours annually, according to government documents, which is the amount of electricity used annually by about 65,000 typical Arizona homes. (About 10 percent of its output is needed to run the plant.)

It produced about 600,000 megawatt hours in its first full year of operation, according to data from the federal Energy Information Administration. That increased to more than 700,000 mwh in 2015. But then the output fell to slightly more than 600,000 mwh in 2016.

As Phoenix New Times reported last year, output dwindled in the summer of 2016 after a microburst knocked out the plant that July.

It took the plant months to recover.

After that, energy production soared for the first six months of 2017, totaling about 429,000 megawatt hours between January and June.

Then, on July 1, the first of two transformer fires took the plant out of commission for several weeks. After one transformer was fixed or replaced, the plant continued to work only at half-power.

"In July 2017, there was an incident with electric transformers in Solana, which caused the plant to produce at a reduced capacity," the public company's August 4 filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission states. "Currently, half of the transformers are in operation and we expect to have the rest in operation by mid-August."

Solana focuses the sun's energy on pipes that contain a nontoxic fluid. The fluid gets pumped to two steam turbines that provide electricity even after the sun goes down.

Ray Stern

"The plant is paying its loan as scheduled with the revenues generated even if performance did not reach" its production goals, Garcia said.

Nor does poor output affect customers of Arizona Public Service, which is contracted to buy Solana's power.

"If they don't produce, we don't pay for it," said Brad Albert, APS' general manager of resource management.

Yet large-scale solar plants owned by Abengoa have helped cause the company financial turmoil that brought it to the brink of bankruptcy last year.

The United States objected in December to a debt-restructuring plan that reportedly caused a loss of $130 million in taxpayer funds. Abengoa plans on selling off Atlantica Yield to pay back money it borrowed to execute the plan.

Abengoa's near-bankruptcy follows several high-profile failures of solar-energy firms under the Obama administration, like the infamous Solyndra.

If it can ever work out its kinks, Solana might well be a good long-term investment for some company. But the plant's lackluster performance, combined with its high price, won't necessarily inspire anyone to build a similar one anytime soon. Experts expect concentrated solar to boom in the next few years — but in Africa, China, and other places without large natural-gas reserves.

Solana also hasn't been as clean-running as proponents hoped.

Richard Sumner, permitting division manager for the county's air-quality department, said last year that leaking heat-transfer fluid at the plant emitted twice as many volatile organic compounds than a natural-gas plant of the same size. His prediction at the time that pollution problems may continue appears to have been correct.

Two months after the record fine, the plant was dinged by a $500 fine for a "missing gasket on a gas tank," said

Bob Huhn, the county department's spokesman.

That was followed by a heat-transfer fluid leak noted in January 2017. That violation was "rescinded" after it was determined the problem was not the company's fault, Huhn said.

Two more heat-transfer fluid leaks were noted in July and August.

The county is still researching those. Huhn said the county could take 60 days to give a final answer on whether to fine the plant or rescind those violations, too. The county allows emissions of 40 pounds per day, but Solana exceeded that on both occasions, he said.

Whether the company is found responsible or not, officials believe the leaks likely caused air-quality problems in the rural area around the plant, Huhn said, and possibly an odor that people may have noticed.

Garcia said that Solana workers continue to monitor the leaks, which the company self-reported.

Currently, the plant is in compliance, he said.

Depending on what county officials determine, however, that could change.