Tuscon resident Gregory McNamee is no stranger to either food history or that of the Southwest, but in his most recent book, he takes readers far into the past and far below the surface level of both subjects for a fascinating and fun historical text (that will probably make you hungry). We caught up with McNamee to chat about the book and the Southwestern food that are most often on his plate.

Tell us a bit about your book. What kind of experience can readers expect to find between the covers?

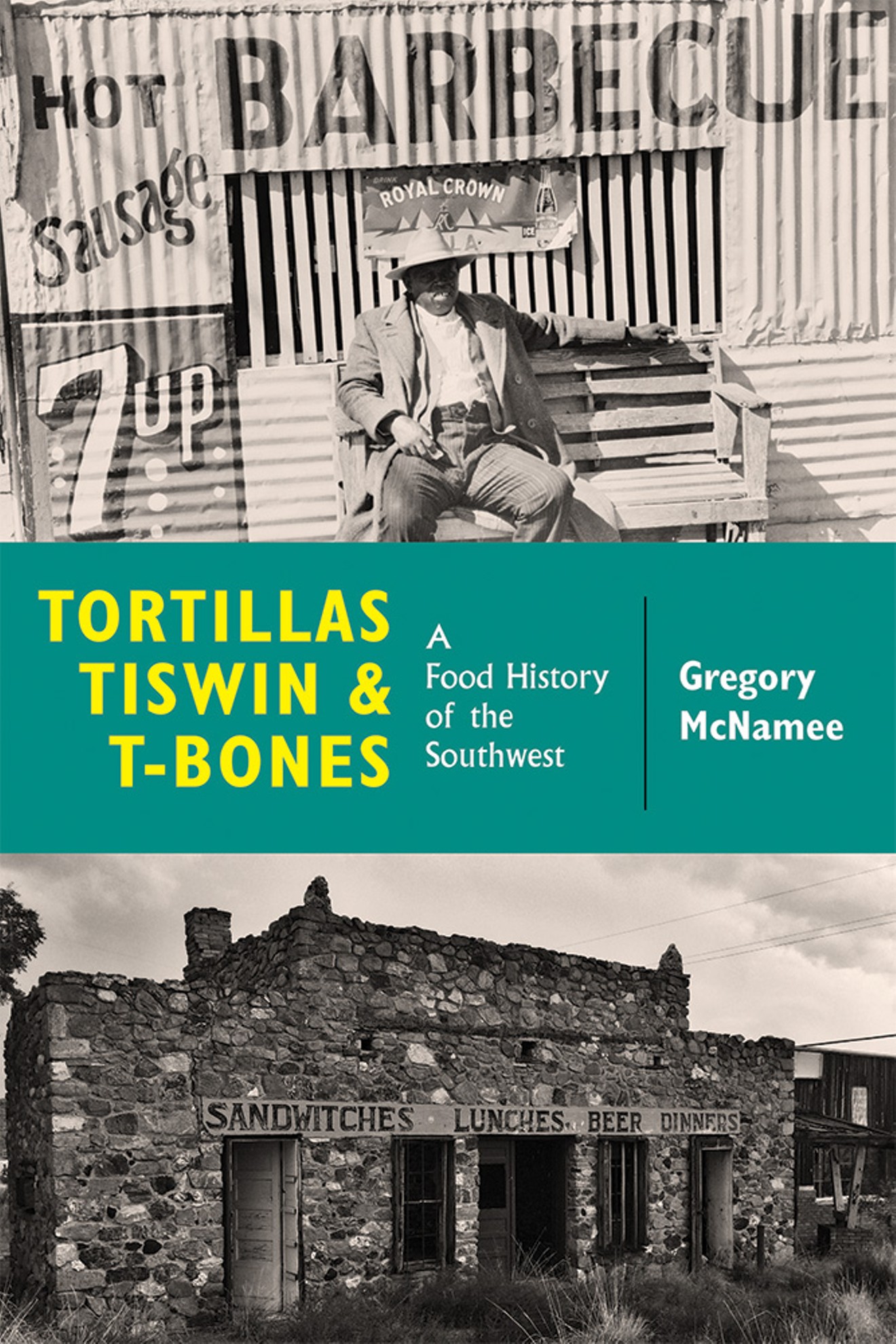

"My book Tortillas, Tiswin & T-Bones is a food history of the Southwest, a region that I take to cover the region of the United States in which Spanish was the dominant European language before English (so, Texas, New Mexico, southern Colorado, Arizona, and California up to the Bay Area). It covers the ground from the mastodons and other megafauna that the first humans to arrive here ate and on to the plant foods of the Southwest; looks into the history of mass foods like Fritos and Rosarita refried beans; and ends with a look at the foods of the newest immigrants to the region and the foods we are likely to eat in the near-term future."

What got you interested in researching the food history of the Southwest?

"I have written many books about the natural history of the Southwest and beyond, including Gila: The Life and Death of an American River and The Ancient Southwest. Nowhere does natural history and human history, my two great interests, come together more than in the realm of food. I’ve written food-related journalism for many years, but saw in this project the chance to stretch out beyond thousand-word word counts to dig in deep to stories like how the tortilla came into being and why it is that we owe barbecue to a confluence of Native American and African-American traditions, things of that nature."

What were one or two things that you found particularly surprising in your subject matter?

"I am always surprised by the willingness of humans to go beyond their squeamishness and ordinary fears to try new things. By way of example: plants in the nightshade family, including potatoes and tomatoes, are toxic to humans in their “wildest” forms. Someone had to breed them to lessen those toxic elements—and someone had to test them out. We’ll have the opportunity to test our own squeamishness in the coming years, when I predict that we’ll be eating a lot of insect-derived protein—grasshopper burgers, that is to say."

In the food world, it’s so easy to get caught up in what’s new. What do you see as the importance of food history?

"The study of food history reminds us foremost that humans are adaptable critters. We eat many of the things we do out of necessity — a broad inventory of plant foods, for instance, because animal proteins were not always available to us. Given an ever-expanding human population, climate change, and the loss of readily available sources of water, we’re going to face considerable challenges in feeding ourselves in the very near future, so we’ll have to be adaptable."

What is your favorite Southwestern food?

"I’ve never had the opportunity to eat mastodon — though it is possible to do so, if you don’t mind a few thousand years of freezer burn. It would be hard for me to narrow down my favorite Southwestern food, especially since I allow such a broad repertory of foods to fall into that category. That said, if you stick me in a corner with a bowl of posole, or a couple of tamales and some beans, I’m a pretty happy guy. In my own kitchen, I alternate between Mexican and Italian food, with occasional forays into Indian and Chinese cuisine and a bratwurst from time to time — all food, as I say, that plays a part in the food history of the Southwest."

What are your hopes for readers of your book?

"I hope that readers of my book will take the pleasure that I do in knowing that behind every item on our dinner plate there’s an interesting story: not just of how some ancient farmer (or perhaps modern agronomist) figured out how to domesticate it, but also how thousands of years of human trade and interaction made it possible for us to eat honey, saffron rice, chicken, oranges, and all the other things we Southwesterners — we humans — enjoy."

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]