Travis Bradley/Cronkite News

Audio By Carbonatix

The George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center wasn’t always a national landmark. Nearly 100 years ago, it was the Phoenix Union Colored High School – a symbolic representation of the reprehensible race relations in the Valley during the 1920s.

Today, it is affectionately known as “The Carver.” Over time, and as a direct result of the dedicated work of historians and social activists throughout the century, it has become a space dedicated to the study of the history and culture of African Americans in Arizona and the American Southwest.

One of the more recent extensions of the museum’s efforts to portray the lives, arts and cultures of African Americans was implemented this past February.

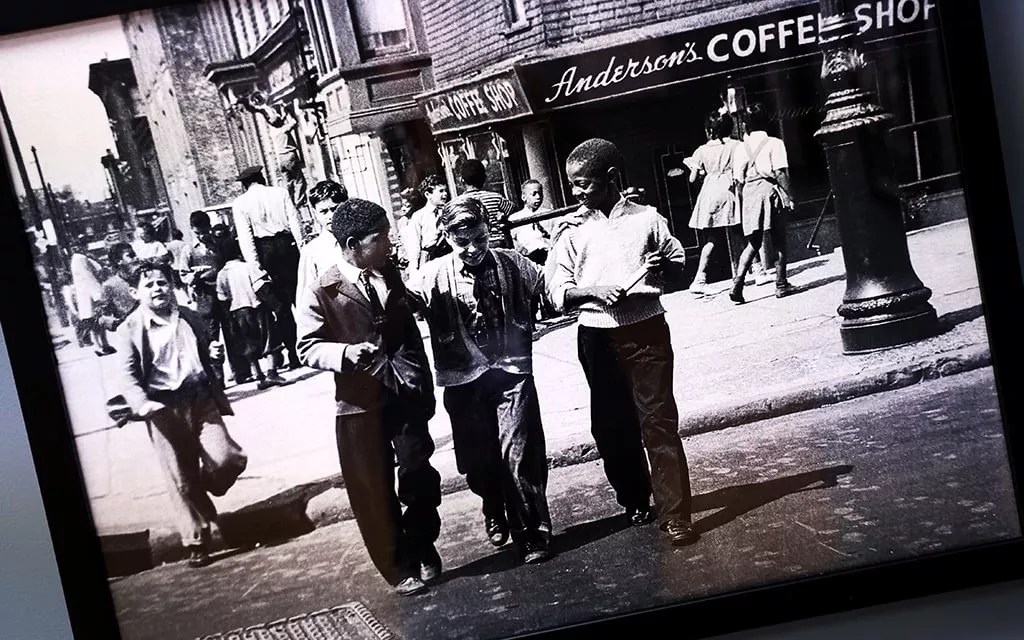

Called the “Black Folk Photography of Joe Schwartz” exhibit, it features the work of Schwartz and several other historically significant black photographers, including Gordon Parks and Deana Lawson.

When news happens, Phoenix New Times is there —

Your support strengthens our coverage.

We’re aiming to raise $30,000 by December 31, so we can continue covering what matters most to you. If New Times matters to you, please take action and contribute today, so when news happens, our reporters can be there.

Schwartz’s life centered around activism, street politics and photographing the “have-nots” and the downtrodden. Growing up in the slums of Brooklyn, New York, Schwartz, the son of immigrants from Poland and Romania, saw firsthand how people from all races and cultures could cohabitate, regardless of the color of their skin or where they went to church.

The idea for the exhibit was conceived during a conversation between Dr. Matthew Whitaker, the executive director at the Carver, and his friend and mentor, Dr. Carl Schwartz, a part-time therapist at Scottsdale Providence Recovery Center and Joe’s son.

“(Carl) mentioned that his father was a well-known Harlem Renaissance photographic artist who had run afoul of some more conservative leaders because of his advocacy in Harlem,” Whitaker says. “He wanted to demonstrate the humanity of the folks who lived in Harlem and the diversity of it. … He wanted to show them in their own environment, navigating and defining and owning that environment.”

In addition to the life work of Joe Schwartz, the exhibit highlights the professional work of historically significant Black photographers such as Gordon Parks and Deana Lawson.

Travis Bradley/Cronkite News

In response to what Whitaker called contemporary “struggles navigating and negotiating interracial relationships,” he knew that he wanted to feature this work in the Carver.

While these types of social issues certainly are not novel, the peculiar nature of racial conflict is that it tends to transform with the times. Ironically, in racially mixed, low-income communities where resources are more scarce than they are in their affluent counterparts, racial differences become secondary to the unanimous struggle for financial security.

Joe Schwartz, who died in 2013 at 99, exemplified this phenomenon in his work, capturing moments of unity and companionship between white and Black residents in financially distressed New York neighborhoods.

“I remember being in the projects when I was young, and you just got used to everybody being poor. In fact, I don’t think anybody thought they were poor at that time,” Carl Schwartz says.

The museum exhibit isn’t targeted solely to African American audiences, Whitaker says. It is meant to display critical aspects of African American history through photographic art as well as speak to other identities and various modes of “othering.”

“We wanted to show the work of this white photographic artist who was deeply committed to Black lives and humanity, but we also wanted to exhibit the work of Black folk artists as well, and we think the exhibit really captures that,” Whitaker says.

The topics and conversations the Carver staff hope to address through the exhibit aren’t exclusive to the metro Phoenix area – they are prominent throughout much of the United States.

Roosevelt and Eunice Randall, who were visiting the Valley from Clinton, Louisiana, toured the museum during their vacation, and they had a particular affinity for the Black Folk Photography exhibit.

The Randalls have been married for 40 years, and in their experience living in the East Feliciana Parish, racial divides are still a prominent feature in many parts of the American South.

Eunice was captivated by the history that the photography depicted, seeing part of her own background reflected in Joe Schwartz’s work.

“A lot of people don’t want to go back and look at the beginning, how things started, things you had to walk through and go through,” Eunice said. “I think it’s important because we don’t often use Black history anymore in the school systems.”

She pointed out the various techniques the photographers used to capture the notability of African American culture in America.

A documentary titled “Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People” plays in the exhibit while visitors look on.

Travis Bradley/Cronkite News

Her husband, Roosevelt, was taken aback by how prominent the Black photographers commemorated in the museum were throughout the inflection points in our country’s history.

“It wasn’t just one or two photographers – there were a lot. They really did a lot more than what we’ve heard about,” Roosevelt said.

Eunice noted that the exhibit inspired her to think deeper on the topic, posing questions like “Why did these photographers do what they did? What encouraged them? What was impressed on them to put everything that they had in themselves out there to everybody else?”

All are questions that the “Black Folk Photography of Joe Schwartz” exhibit intended to provoke in its visitors.

Whitaker was born and raised on the southwest side of Phoenix, and he’s been a long-time resident of Arizona. As someone who has unmediated experiences with the ebbing and flowing of race relations in the Valley, he sees an additional purpose that the exhibit can bring to the community.

“Hopefully, this exhibit closes the gap by getting to the core of who we are,” Whitaker says, “just human beings trying to eke out a living and to get some joy from the freedom that we have.”

The George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center is on summer hiatus through July 31. Visit the museum’s website for updates and to see its virtual exhibits.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.