Craig LaRotonda

Audio By Carbonatix

For more than a decade, Mary Piña and her family were haunted by the repercussions of a few grams of marijuana that Phoenix police found during a traffic stop.

In 2010, after being pulled over for a minor traffic violation, Piña’s 18-year-old son was stuck with a felony charge for drug possession. For years, the conviction followed him. It was a red flag on his background checks. It kept him from a stable job.

Earlier this fall, though, things changed again, this time for the better, when the drug charge became the equivalent of a lottery ticket.

It qualified him and his family in Maryvale to enter into a lottery for a dispensary license through Arizona’s new “social equity ownership” program. Voters had enacted the idea to offer a form of reparations to communities that had been disproportionately and excessively harmed by harsh pot enforcement laws.

Suddenly, that decade-old charge was no longer a point of shame. It was valuable. Piña found herself and her family being courted day and night by an investor who wanted to partner with them to apply for a license.

That prospect of redemption was brief. Now, Piña says, she is disillusioned with the program.

“I feel cheated,” she said. “And lied to.”

Last fall, across Arizona, cannabis companies and investors with deep pockets assembled pools of applicants like Piña from low-income communities and communities of color. They were to front bids in the lottery for social equity licenses, the last of 169 dispensary licenses that the state will award. This spring, 26 of those names will be plucked from the hat and given a dispensary license.

Many pot industry analyists place the value of that asset conservatively at around $8 million, but some industry investors estimate it could be worth as much as $15 million, according to legal documents obtained by Phoenix New Times.

Phoenix New Times also obtained and analyzed data about the 1,506 applications submitted to the Arizona Department of Health Services. The data show that major industry players backed most of these applications, vying for a slice of the profits from a program ostensibly meant to benefit disadvantaged entrepreneurs.

At least 58 percent of the applications submitted to the state have ties to industry money or major investors, New Times found. Hundreds of applications were backed by established multi-state operators that already have dispensary licenses in Arizona, such as Mohave Cannabis Co.

Others are tied to more shadowy corporate entities. Two shell companies with business addresses listed in Cheyenne, Wyoming, backed more than 200 applications. And another limited liability company in New Mexico, whose true owner was not apparent from public corporate documents, backed another 78 applications.

One was Piña’s son.

Critics of the social equity program’s rollout say that the applicant pool is vindication – proof that they were right to warn that the state of Arizona was not doing enough to keep Big Pot from tipping the social equity scales to its advantage.

“We predicted everything that took place,” said Celeste Rodriguez, a long-time critic of the social equity lottery and a principal at cannabis company Acre 41. Rodriguez and Acre 41 sued the state over the program, but the case was ultimately dismissed.

Not everyone finds fault with the infant program.

“It’s a win-win for all parties if we are fortunate enough to get selected in the lottery,” wrote Curtis Devine in an email.

He owns Mohave Cannabis Co., which worked with more than 180 social equity applicants.

“If the social equity applicant wants to sell, I’m happy to buy,” Devine said. “If they want to stay in the game, I’m happy to help them create a prosperous business.”

In a statement to New Times, Steve Elliott, a spokesperson with the Department of Health Services, wrote that “everything ADHS has done to establish an adult-use marijuana social equity program is in accordance with requirements in the voter-approved law.”

Elliott added the state agency was reviewing the applications carefully to ensure they did not violate the state’s rules.

Contracts obtained by New Times illuminate some of the details offered to applicants. Critics say they reveal key loopholes in the state’s rules that allowed investors to take advantage of applicants.

The contract that Piña’s son signed, with a shell company called “Social Partners, LLC,” directs a third-party management company to siphon out all of the company’s profits, should he win a license. Under the agreement, which one industry attorney criticized as “deeply predatory,” the Piña family would be given a $50,000 payout for a business likely worth millions.

Despite his status as owner, Piña’s son would receive none of the business’s annual revenue.

Looking back, Piña said she feels like she and her family were taken advantage of. New Times agreed not to name Piña’s son, who signed a non-disclosure agreement as part of his application. But New Times did review months of text messages, contracts, and other documents related to his case.

“I want the state to know that the Wolf of Wall Street is in Maryvale, targeting low-income families,” Piña said.

Opportunity of a Lifetime

It was October when Mary Piña was first approached by a social equity investor.

Piña remembers that initial conversation was with Susana Espinoza, who said she was working with an investor at Social Partners.

“The family suffered at the time [of her son’s charge],” Piña recalled Espinoza telling her. “You were worried about your son.”

The license, she said, could fix that.

According to text messages and Piña’s account of the process, Espinoza was working as an intermediary for an investor interested in a license, recruiting people in west Phoenix to submit applications.

Reached by phone, Espinoza first claimed she had “nothing to do” with the social equity licenses. Pressed on the details and the identity of her employer, however, she said she had to speak with him first, and then ended the call and did not return further inquiries.

At first, Piña said she was all-in. The offer was hard to pass up. Just for applying, members of her family, if they qualified, would each receive $500 cash – even if the family did not win the license. Also, the investor’s lawyers would petition to have her son’s charge scrubbed from his record through the state’s new expungement process for low-level pot charges.

And anyone who was granted a license would get a $50,000 payout. For Piña, a single mother and renter, who still helps support her adult children, this kind of money would be life-changing, she said.

Piña agreed to apply.

As the weeks went on, though, Piña began to have doubts. She began receiving constant calls from Espinoza – multiple times a day, sometimes at seven or eight in the morning. Espinoza was asking for one piece of the application or another, warning that if the investor didn’t get documents on time, the family would be dropped from the application pool. Piña said she felt it was borderline “harassment.”

Over several months, Piña provided her family’s fingerprints, tax information, and social security numbers to the investor’s attorneys. She herself didn’t enter the lottery because she was eventually told she didn’t qualify. But her son ultimately signed a 39-page contract, and his name was tossed into the pool.

Piña was busy with work and with her family. She had little time to pause to read the documents she was signing – even less to call up a lawyer. Neither she nor her son had time to go through the training that the state had mandated for applicants. It provided education on the program’s details and ways to avoid deals with what the state called “predatory investors.” But no matter; the investor did it for them, Piña said.

She now regrets not asking for an outside legal opinion. “They knew who to target,” she said. “Because they know we have to work.”

When she expressed doubts to Espinoza after all the paperwork was submitted with the state, the woman wrote back: “When do you or your family get an opportunity like this dangled in your faces?”

The Lottery Pool

Over the course of the fall, investors and companies interested in submitting a bid for the license went to great lengths to find families like Piña’s, who were qualified for the program based on their income, ZIP code, and prior pot charges.

All of the 1,506 applications to the state lottery are fronted by a qualifying applicant, someone in Arizona who meets the state’s requirements of being “disproportionately impacted” by the war on drugs.

Each application is attached to a company, which must be at least 51 percent owned by a qualified applicant. The other 49 percent of the company could be owned by anyone – an investor, a management company, or an applicant’s friend.

At least 878 applicants are backed by a major cannabis company or an outside investment group, according to New Times‘ analysis of corporate filings by companies that have entered the lottery.

To analyze the applications, New Times looked at submissions that shared a business address, an agent, or principal in the company. The remaining 600 applications did not have clear ties to a single investor, based on Arizona Corporation Commission filings.

Some of the numbers posted by Arizona’s biggest cannabis companies – which already have recreational dispensary licenses – are significant. Mohave Cannabis Co., which now operates in three states, backed 368 applications. Copperstate Farms, which operates Sol Flower brand dispensaries across the state, backed another 110. Mint Cannabis was involved in 90 applications.

These big cannabis companies took no measures to conceal the number of applications they submitted to the lottery. In press releases for its program, Copperstate openly touted its efforts, saying that it had created a system that “gives social equity applicants a support system and the infrastructure to submit a strong dispensary application.”

But other investors kept their identity from the public.

One unknown investor or investment group submitted more than 200 applications to the lottery, or around 14 percent of the pool. Its identity traces back to two shell companies registered at an address in Cheyenne, Wyoming, called “Helping Handz, LLC” and “Investing in the Future, LLC.”

Cheyenne has been dubbed “a little Cayman Island on the Great Plains” due to the number of shell companies registered there. The limited state oversight of corporate filings in Wyoming makes it an ideal state to register a business without divulging its true ownership to the public.

The Mint Dispensary on Priest Drive at Baseline Road: Mint Cannabis and Copperstate Farms are two local companies that have backed a number of social equity applicants.

Jacob Tyler Dunn

Critics say that the involvement of these companies defeats the purpose of a social equity program. The mission, they say, should be to even the playing field in an industry already stacked against under-resourced communities.

“The system is operating exactly how it was designed to, to be favorable toward already-existing industry players,” said Julie Gunnigle, an attorney and former political director for Arizona NORML.

Still, she said, some of the numbers analyzed by New Times were “shocking.”

The cannabis companies involved in the process, however, say that their involvement gave applicants a chance they would not have had otherwise.

“Most of the applicants [we worked with] were not even aware of the program, so it’s very unlikely any of them would have applied without our assistance,” said Devine, the Mohave Cannabis founder.

New Times contacted multiple executives with Copperstate Farms and the Mint by phone and email over the course of several weeks. Neither company returned any inquiries nor offered any comment.

Companies found large numbers of willing applicants mostly with extensive advertising campaigns. They put up billboards, distributed flyers, and canvassed door-to-door. Copperstate Farms created an entire website – Your Bright Horizon – for its campaign, highlighting that it would assist applicants in expunging prior marijuana charges if they went through its social equity process.

“We worked day and night reaching out to potential applicants,” said Devine, the owner of Mohave. “There wasn’t a magic button, just a ton of work. I met with and spoke to every applicant individually to discuss this program and opportunity.”

Piña, meanwhile, still does not know the identity of the individual investor that worked with her family.

The investor’s identity is well-concealed by a series of shell companies that dead-end in New Mexico. The true ownership is not reflected in corporate filings obtained by New Times.

New Times did find, though, that the same investor had submitted another 76 entities – representing 38 separate applicants – into the lottery, securing a decent chance of winning at least one of the licenses.

The state’s rules allowed each applicant to submit two bids. The vast majority did. This enabled applicants to double their odds of the big payout, but also meant the state could collect twice as many application fees. At $4,000 a pop.

Attorney Julie Gunnigle: “The system is operating exactly how it was designed to, to be favorable toward already-existing industry players.”

Ash Ponders

Rules of the Game

When faced with criticism over corporate influence, defenders of the big cannabis companies have an easy scapegoat. Blame the rules.

The rulemaking process dates to November 3, 2020. On that day, Proposition 207 – the massive voter initiative that legalized recreational marijuana in Arizona – passed, clearing the way for the lucrative industry to take root in the state.

A key provision of Prop. 207 was the establishment of a “social equity” ownership program. For the many civil rights groups that had lobbied for the legislation, the social equity program was a tacit promise that the riches of Arizona’s green rush would not all end up in the hands of a wealthy, largely white, industry elite.

Prop. 207 proponents called the program a form of restitution for those communities that bore the scars of Arizona’s decades-long war on drugs.

The details of the program, though, were left to Arizona bureaucrats.

Over the next year, Arizona’s Department of Health Services crafted the rules for the program. Leading the charge was Roopali Desai, a lawyer with Coppersmith Brockelman. She was a central figure in the effort to pass Prop. 207 and was described by those who know her as a dogged attorney. She and her firm quickly began working on the social equity rules.

Early drafts of the rules came under fire for being relatively sparse, at only 10 or so pages, and for having loose application requirements. “They put no thought into it,” Rodriguez, a principal at Acre 41 and one of the program’s earliest critics, told New Times in May.

The final rules, which were ultimately released in November, laid out more detailed qualifications for applicants. Applications had to meet three of these four requirements:

Having a prior marijuana conviction.

Having a spouse, a sibling, or a child with a prior marijuana conviction.

Earning an annual household income below 400 percent of the poverty level. For a single person, that’s around $52,500.

Living in a qualifying ZIP code.

Applicants also had to sign a statement that “neither the principal officer nor board member nor the applicant has, directly or indirectly, entered or promised to enter into any agreements for a change in ‘ownership.'” In essence, they promised they had not agreed to sell the license off before it was awarded.

Rodriguez and other advocates immediately had questions.

Without any provision that required licenses to stay in the hands of social equity applicants, how would the state prevent them from quickly falling prey to a well-financed industry? How would under-resourced applicants navigate a byzantine application process?

“We predicted everything that took place,” said Rodriguez, referring to cannabis plutocrats sponsoring as many applicants as they could. As a Black woman in the industry, it was “disheartening” to watch it all play out, she added. From the beginning, she told Desai and the state about her concerns. But they were ignored, she said.

Acre 41’s Celeste Rodriguez “predicted everything that took place”with the social equity license program.

Tom Carlson

Acre 41, together with the Urban League, a civil rights group, sued the state in a last-ditch effort to get the Department of Health to go back to the drawing board.

Acre 41 alleged that the final rules of the program were so weak that they ultimately failed to live up to the requirements of the statute, which mandated the state establish a program to “promote ownership and operation” of dispensaries by people from the most-harmed communities

But in early February, a Maricopa County Superior Court judge dismissed the case, clearing the way for Arizona to award the licenses. The court decided not to intervene in the program’s specifics.

“Whether this was the best way to structure the program is not for the court to decide,” Judge Randall Warner wrote in his final opinion. The Arizona Department of Health Services had written rules that were “reasonable” under the statute, which left no room for a legal challenge, he found.

Desai did not return New Times‘ requests for comment on the rulemaking process. But in court this month, she emphasized that the state had spent months coming up with the rules and considered concerns raised by Rodriguez and others.

“What we’re doing in 30 minutes this morning has occurred at the department over many, many, many months,” she told the court during a hearing. “At the end of the day, the mandate to the department was to adopt rules to develop, to promote, a social equity ownership program.”

“Throughout this stakeholder process, ADHS listened and made improvements to the rules in large part due to the constructive conversations with potential applicants and experts,” Elliott, the DHS spokesperson, wrote.

Still, some in the industry think that there was clear influence from Big Pot in the rulemaking process.

“The MSOs [multi-state cannabis operators] in every state and in every region are applying significant pressure” on social equity programs, said Jeffrey Tice, a former dispensary license holder who now runs a cannabis advisory firm in Phoenix. He worked on multiple social equity applications. This was no different in Arizona, he said.

“I would say that the large companies had significant influence in the regulatory process,” Tice said.

Demitri Downing, founder of the Marijuana Industry Trade Association, said the industry deserves credit for its equity efforts, even if it plays an outsized role in the program.

“Cannabis is one of the only industries that is actually trying to define and get deeply involved in reparations, social equity policy,” Downing said. “That doesn’t happen very much in real estate or restaurants or banking.”

“Our cannabis industry is wrestling with it,” he said.

Striking a Deal

With Acre 41’s legal challenge out of the way, the state is currently reviewing applications and plans to name 26 lucky winners sometime in the coming weeks.

Some in the industry say they expect those 26 licenses to fall quickly under the control of cannabis behemoths.

“There are a lot of sharks out there. I know and meet with those sharks every day,” said John Labate, who runs the cannabis consulting firm Green Brick Road. Labate calls himself a “gun for hire” in the industry. He works with cannabis firms looking to move to Arizona along with established industry players.

“I know, point-blank, what their agenda is,” he said of the companies that had backed hundreds of applications, citing his own conversations with people in the industry. “It’s to get ownership of one of these licenses by applying capital.”

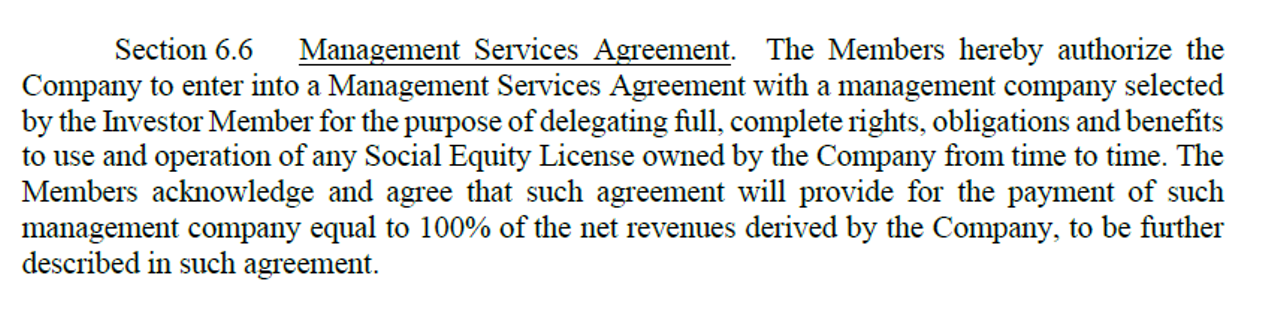

In Piña’s case, the investor retained a local firm, Rose Law Group, to draft the operating agreement that it offered applicants. The 39-page contract, obtained by New Times, sheds light on how easy it can be for companies to wrest control of a social equity license away from an applicant.

The contract signed by Piña’s son awards him 51 percent stake in the company, as required by the state’s rules. But take a closer look, and it’s clear that his role in the company carries almost no weight.

The Rose Law Group contract says that if Piña wins a license, the day-to-day operation of the company would transfer to a management company. That company would be “selected by the [investor] for the purpose of delegating full, complete rights, obligations and benefits to use and operation of any Social Equity License owned by the company.”

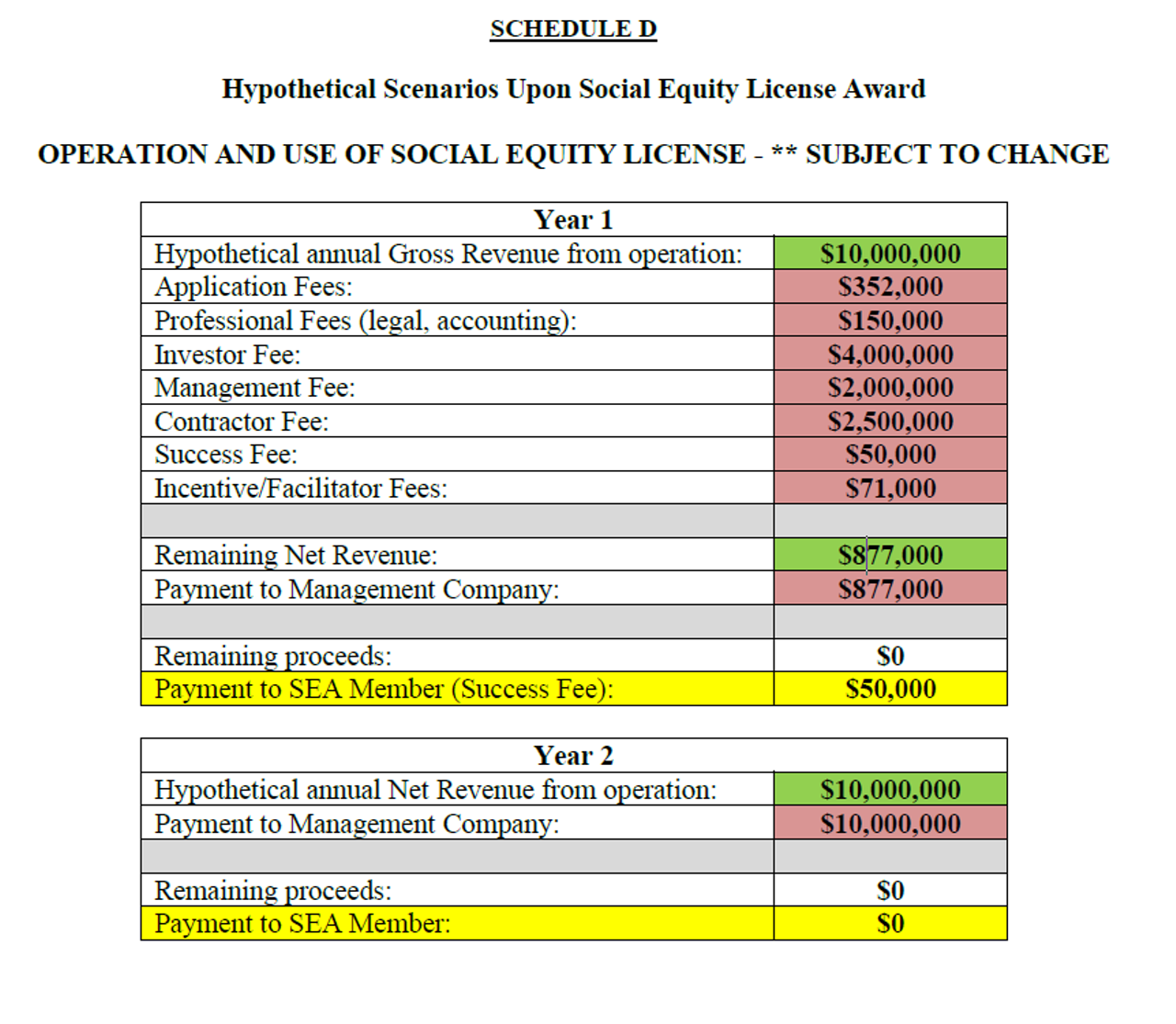

Contractually, the management company gets 100 percent of the net revenues. The applicant? ,000.

Screenshot

In the hypothetical scenario presented in the contract to Piña, this management company would collect “100 percent of net revenues derived by the Company” – leaving the applicant only with a $50,000 “success fee” in the company’s first year. Most dispensaries are expected to generate millions in revenue.

In subsequent years, assuming nobody sells the license, the management company is entitled to all of the dispensary’s net revenues. The social equity applicant would not be entitled to even any success fees, the contract spells out.

Jimmy Cool, a business attorney who worked on Acre 41’s case against the state, called the contract “deeply predatory.”

According to the contract, he said, the social equity applicant’s role would be reduced to “a voting obligation in a company where none of the votes matter and they don’t make any money.”

Gunnigle, the attorney and advocate, said that the contract was a clear attempt to “wrestle control away from the social equity applicant.”

A breakdown of where the money goes from a sample contract.

Screenshot

Downing, the trade industry leader, said he found the contract interesting, but not a cause for concern. The applicant got the $50,000, he said. “This is a program with options,” he said. “People don’t have to take them.”

The Rose Law Group agreement does not appear to violate any of Arizona’s rules, according to both Cool and Gunnigle.

Those regulations require the applicant to have “at least 51 percent ownership” of the company. But all decision-making power, per the contract, is vested in a third-party management company.

The state also mandates an applicant be entitled to an equivalent “portion of distributed profits.” In this agreement, for example, the Piña family would be due 51 percent of those profits. But 51 percent of nothing is nothing.

First, the outside management company collects all the costs, in the form of various set fees. If there are any remaining profits, the language requires the outside management company would collect all of that, as well.

In this way, the Rose contract language could skew how much those profits might trickle down to an applicant like Piña. In theory, the applicant is entitled to the majority of those profits. But in reality, as written, the contract calls for the company to pay a series of management, investment, and contractor fees. The remaining proceeds would go to the outside management company, leaving just $50,000 for the applicant. And in subsequent years, not even that.

“You can enter into an agreement that technically conforms to all their restrictions but in no way serves the spirit of those restrictions,” Cool said. The contract, he said, was a clear example of this.

“This agreement is a really good illustration of the primary concerns I have with the [state] rules as they currently stand,” Cool said.

Also, the Social Partners contract lays out a hypothetical scenario if the license were sold. It says Piña’s son would receive his proportional share after the costs of the sale are paid. He would get $2.6 million in a $15 million sale, closer to 17 percent than the 51 percent he thought was his share.

The implication from the two scenarios is clear: Take the buyout, or be left with nothing after the first year.

New Times submitted a public records request for detailed application information on Piña’s son from the state in early January. The state has still not released the documents.

In reply to New Times‘ questions, Elliott, the DHS spokesperson, did not directly respond to a question asking whether the state was proactively reviewing the contracts given to applicants. Instead, he said the agency “investigates complaints alleging violations of regulations by a licensee” and would take enforcement action if necessary. But so far, he said, the state had not received any complaints.

Jon Udell, political director of Arizona NORML and one of two primary cannabis attorneys with Rose Law Group, is listed on the contract as its author. Udell did not reply to multiple texts from New Times inquiring about his work on the contract or the identity of the investor.

No company contacted for this story was willing to provide its own operating agreements. Devine, the Mohave founder, said that social equity applicants signed non-disclosure agreements, preventing the company from releasing specifics. The contract agreements, he said, were “in line with the intent of the program.”

Still, even amid the sea of investor-backed applicants, there are some who embarked on the process alone.

A Different Way

In 1989, when Alexander Tam was 22, he was caught up in a marijuana drug bust.

Undercover deputies with the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office had caught on to some friends of Tam’s and began orchestrating a sale. It was, Tam recalls, “all talk.” He said no money or drugs were exchanged, which police reports confirm.

Regardless, Tam was charged with felony drug possession for sale. He took a plea deal.

“I didn’t know any better,” Tam, who is Asian and Latino, recalls now. “I was a kid.”

The charge upended his life. His father owned a small restaurant in Scottsdale, which Tam was poised to take over. After the conviction, his father sold it. Tam worked odd jobs over the years, instead – in trucking, in agriculture, in landscaping. With a felony on his record, entire career paths were suddenly closed off to him.

“I still pay for it, to this day,” Tam said.

Now, he is applying on his own for one of the state’s social equity licenses. He says he sees it as a chance for redemption.

Alexander Tam considered partnering with well-funded investors but chose not to.

Tom Carlson

He had no financial backing – he charged the $4,000 fee to his credit card, he said, and prayed that the transaction wasn’t declined. He barely got his documents together in time, submitting his application just minutes before the deadline.

He had considered partnering with well-funded investors but chose not to. What mattered to Tam was not the money that a marijuana dispensary promised. It was the ability to run it – to operate it, and use it to give back to his community. To create the legacy that a drug felony had denied him for decades.

Tam said that he expected an investor to offer “a couple [of] million bucks and a pat on the head. And that’s not a legacy. That’s a buyout.”

Another social equity applicant, Jeffrey Nelson, said he had initially been courted by Copperstate Farms, after poking around to see if he qualified for the program.

Nelson grew up in Maryvale and now lives in central Phoenix. Although he does not have a marijuana charge, his father did, qualifying him for the program.

Initially, Nelson thought he would go forward with the partnership with Copperstate. But when he watched one of the state’s training videos on predatory investors and deals, he said, “red flags started popping in my head.”

When he asked questions, he said, he was refused answers, “exactly” as the video had warned against. Nelson decided it was better to apply alone and partner with some of his cousins.

“We’re going against big companies and we’re probably not going to get it,” Nelson said. “But I can’t live with the fact knowing that I could have applied and I didn’t.”

Jeffrey Nelson (left) with his cousins and partners Zach and Dillan Nelson. Nelson considered partnering with Copperstate but when he watched a training video on predatory investors “red flags started popping in my head.”

Tom Carlson

For Tam, the suggestion that those who qualify as social equity applicants are incapable of going through the process alone is patronizing.

“The big businesses are saying, we’re a necessary evil,” he said. “You need to use us because you don’t have the money, you don’t have the resources, you don’t have the know-how.”

“I don’t believe that,” Tam said.

Still, Labate, the pot industry’s hired gun, is skeptical. He said it would be difficult for applicants to spearhead their own venture, even if they managed to make it through the application process without outside assistance.

“Even a really intelligent, really experienced operator could absolutely be led to slaughter,” Labate said. “You’re going to have to go find money somewhere, sometime.”

“If you’re truly qualified,” he said, “you don’t have the bandwidth to get your store up and operating.” The state’s income restrictions ensured this. A dispensary could bring in millions in revenue, he said – but it also has major upfront costs, in real estate, in legal fees.

People like Nelson and Tam, Cool said, could pose the next legal challenge to the social equity program, if they decide to sue over companies diluting the application pool.

Rodriguez said she and her colleagues at Acre 41 plan to lead further efforts to challenge the program.

“Why should we expect anything more or less from a system that has been built by the people who benefit most from it?” Rodriguez said after the judge’s ruling dismissing her original case. She was “disappointed,” she said, but vowed that she would “continue to fight for those who truly deserve and need social equity.”

“We will be heard,” she said.