O’Hara Shipe

Audio By Carbonatix

Surrounded by thousands of cannabis plants in their massive Phoenix cultivation center and concentrate lab, Mike Anton and Jon Pilkington – co-owners and founders of TruMed and Drip – have come a long way.

While recreational cannabis in Arizona became legal under Proposition 207 in 2020, the roots of marijuana consumption in the state sprouted almost three decades ago.

In 1996, 65% of Arizonans approved Proposition 200, a measure that acknowledged the viability of treating debilitating illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, glaucoma, cancer and AIDS with Schedule I controlled substances, including cannabis. Wrapped within the proposition was a provision for probationary sentences for non-violent offenders charged with the possession of controlled substances.

“Pilot programs in Arizona that provide treatment alternatives to prison for low-level drug offenders have a 73% success rate and cost roughly one-eighth as much as prison,” the proposition description indicated.

Just a few months after passing, faulty language in the bill and federal regulations against doctors issuing prescriptions for Schedule I drugs left the proposition defunct. Changes to the language of the legislation were instituted, but Arizona voters shot the revisions down in 1998 and 2002.

Although Proposition 200 left a lot to be desired in terms of making cannabis both safe to grow and consume, it was the humble beginning of the flourishing Arizona industry that raked in $1.4 billion last year. It was also the first glimmer of hope for future cultivators such as Anton and Pilkington.

TruMed co-owner and founder Jon Pilkington has a love of designer brands and cultivating boutique cannabis.

O’Hara Shipe

Healing hands

When Pilkington and Anton first dipped their hands into growing cannabis, it was under the Medical Marijuana Caregiver Program. Established prior to full medical legalization in 2010, the program enabled independent growers to cultivate up to 12 cannabis plants for no more than five registered patients – for a total of 72 plants. However, vaguely written rules and a lack of enforcement hindered the program’s success.

“There was a year-and-a-half period where no dispensaries [in Arizona] were issuing patient and caregiver cards, yet there was nowhere to get medicine,” Pilkington told Phoenix New Times.

The result was what Pilkington calls a “pseudo market” when caregivers were cultivating cannabis free of charge to licensed patients. “Legally, we couldn’t sell cannabis to these patients. They could help offset the cost of growing by paying for lights or something, but they weren’t buying weed per se. It was an interesting market,” Pilkington said.

The highly nuanced legality of the caregiver program meant that cultivators were fueled by a passion for helping chronically ill individuals, not by dreams of making a fortune. And even for those who followed the rules, it was still a risky endeavor.

“Arizona was one of those states where it’s not just a slap on the wrist if you get caught with too much [cannabis] – you’re going to jail for a long time, even during the caregiver program,” Anton explained. “If you harvested 10 pounds [of flower], you were still only able to possess two-and-a-half ounces per patient, so you were out of compliance.”

For highly successful growers such as Pilkington and Anton, the chances of being charged with noncompliance were high.

“Sometimes the police would stop by before you dried the plants so they would be full of water and weigh more than the allotted ounces you could have. Or if they stopped by when you had just harvested and you didn’t cut the number of stalks in a pot, they could count it as more than one plant. It was crazy,” Anton said.

Still, for Anton and Pilkington, the benefits outweighed the potential consequences.

“To hear someone say that you made their life easier, or that they can do things they couldn’t do anymore because of the relief you’re giving them is why we do this. The ability to really change someone’s life – now, that’s really something,” Pilkington said.

Formerly named Oreoz, Double Stuffed is known for its black leaves and frosty trichomes.

O’Hara Shipe

‘We saw an opportunity’

On Dec. 14, 2010, Proposition 203 – the Arizona Medical Marijuana Act – was adopted. The proposition replaced the caregiver program and established steadfast rules for the cultivation, purchase and possession of medical cannabis.

It was the big break Pilkington and Anton had been waiting for. Without hesitation, they used the existing zoning rules to find locations for a grow and dispensary, ponied up $150,000 and submitted an application for a medicinal license lottery. Proposition 203 allowed just 124 dispensary licenses to be issued statewide, so it would take luck to land one.

“I don’t think a lot of people knew what to do for the first lottery. Some applications listed buildings that wouldn’t pass zoning. If they were selected, they would have gotten the license, and we would have missed out, even though we had everything 100% to the letter of the law. It definitely wasn’t guaranteed,” Anton said.

Obtaining a license may not have been guaranteed, but it very may well have been predestined.

By the time Proposition 203 passed, Pilkington and Anton already had a loyal following and earned a reputation as top-tier flower producers.

“[Pilkington and Anton] spent a year and a half under the caregiver program really polishing their craft and getting more involved with genetics. It made for a super smooth transition into former TruMed when they were awarded a license,” said Alex Sternheim, TruMed’s wholesale director.

By 2013, TruMed had a brick-and-mortar dispensary in Phoenix and was serving hundreds of medical marijuana patients a day. Pilkington, Anton and third co-owner Ramzi Dugum become so successful that they had a hard time keeping flower from flying off the shelves.

“We’d post a new strain drop on Instagram, and we’d be completely sold out of it in hours. It was actually kind of crazy,” Anton said. “At the same time, it’s hard when you run out of something that really helps a patient feel better. So, it can be a double-edge sword.”

If being wildly successful was one edge of the sword, the other was innovation.

One of Drip’s most popular products, Caviar, is made from cannabis nugs dipped into melted shatter and rolled in kief.

O’Hara Shipe

Concentrated efforts

In 2018, Pilkington, Anton and Dugum collaborated with Jared Priset, who holds a degree in microbiology from the University of Arizona. The goal was to turn TruMed’s flower into a more potent consumption medium – concentrates.

Just as TruMed had been at the forefront of the medical marijuana movement, its new endeavor – Drip – put them ahead of the curve for creating concentrates. The only problem was that Proposition 203 did not include specific language addressing the production and distribution of products such as cartridges, distillates, topicals and edibles.

Unlike flower, concentrates are distilled versions of the most desirable parts of cannabis sativa plants – the cannabinoids and terpenes. Both compounds exist within the trichomes – the sparkly white substance on dried flower – and are the driving force behind the aroma, flavor and effect of each cannabis strain. In essence, concentrates provide consumers with the most medicinal properties of the plant in the highest potency possible.

While the intent of Proposition 203 was to enable eligible patients to consume legal amounts of marijuana without the fear of persecution, county attorneys in Maricopa and Yavapai argued that the law didn’t apply to concentrates.

A 2018 case, State of Arizona v. Rodney Christopher Jones, sought to overturn the 2013 conviction of Jones, who was arrested with 1.4 grams of hashish in a jar in his backpack. The battle, which would set a precedent for the legal distribution and consumption of concentrates, left the fate of the newly formed Drip in the hands of the Arizona Supreme Court.

On May 28, 2019, nearly a year after the appeal was filed, the court overturned Jones’ conviction. “We hold that [Arizona Medical Marijuana Act’s] definition of marijuana includes both its dried-leaf/flower form and extracted resin, including hashish,” the court stated in its unanimous ruling.

With the legality of concentrates settled, Drip pulled up its bootstraps and went to work.

Jared Priest pours freshly extracted live resin.

O’Hara Shipe

‘Soil to oil’

Because concentrates were still relatively new to the Arizona market, Priset spent much of his time experimenting with the best way to distill TruMed’s flower.

“There was a lot of [research and development] – like we spent a lot of time reading forums, playing with different forms of extraction and testing. Even with the testing and the standards that there were, everyone was still trying to figure out how to calibrate the machinery to make the cleanest product possible,” Priset recalled.

TruMed, and now Drip, had always been patient-focused, so Pilkington, Anton and Dugum weren’t content to merely meet the industry standard for clean concentrates.

The oil extraction process includes harsh chemicals, such as N-butane, isobutane, propane or heptane. Once the oil is been removed from the plant, solvents used in the process are purged from the resulting concentrate to ensure product safety.

Often, residual solvents are left in the final product – the industry allows as much as 5,000 parts per million to be present. “That number wasn’t going to work for us,” Pilkington said. “We wanted it to be zero parts per million because we were working with really ill people. The last thing we wanted to do was provide a product that had something that could potentially harm them.”

It was an arduous process that included creating proprietary equipment and techniques to achieve the kind of product purity Drip was aiming for. But Pilkington said that Drip achieved its goal. “You know, I think that is the Drip difference. We don’t just want to create good products; we want to create the best. We already knew we had amazing flower. Now we can say we have world-class products from soil to oil,” he said.

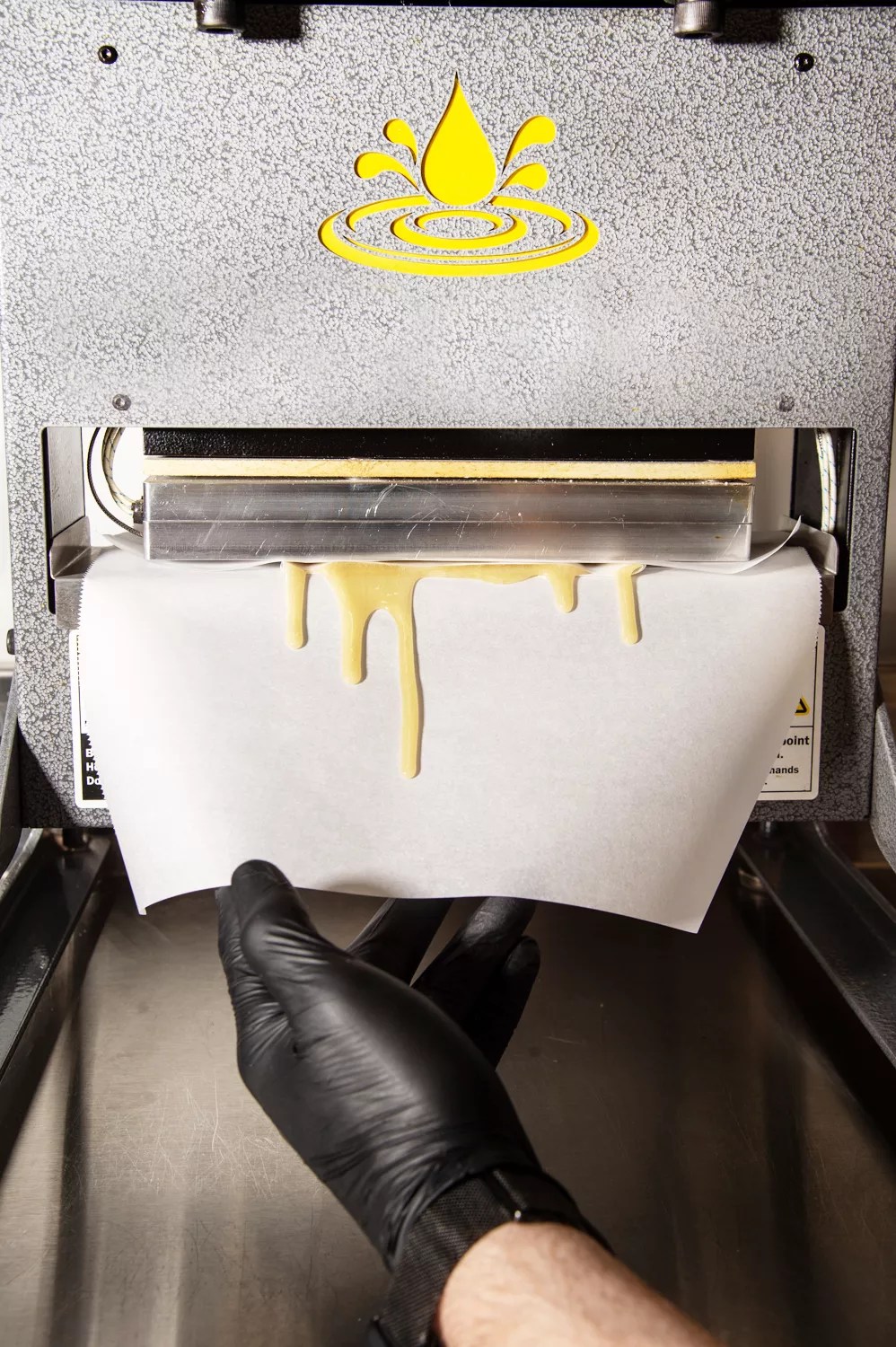

Freshly pressed rosin drips down a sheet of wax paper.

O’Hara Shipe