Wikimedia

Audio By Carbonatix

At 10 o’clock Wednesday morning, Arizona carried out its first execution in nearly eight years.

Clarence Dixon was sentenced to death more than a decade ago for the murder of 21-year-old Deana Bowdoin, an Arizona State University student who was found strangled and stabbed in her home in 1978.

It took decades for Dixon, 66, to even be identified as a suspect in Bowdoin’s death. His last appeal, to the U.S. Supreme Court, was rejected less than an hour before his death sentence was carried out.

Dixon was executed with pentobarbital, a lethal drug that the state spent years trying to obtain. According to media witnesses of his death at the state prison in Florence, all went mostly according to plan. Minutes after the drugs were injected, at 10:19 a.m., Dixon appeared to stop breathing. He was pronounced dead at 10:30 a.m.

Leslie James, Bowdoin’s sister, told the press after Dixon’s death she believed justice had been served. “This is finality for this process. It’s relief. It was way too long,” she said.

Before his final appearance, Dixon asked for Kentucky Fried Chicken and a half pint of strawberry ice cream.

In the execution chamber, Dixon didn’t appear to experience pain, witnesses said. He did make several comments to the doctors as they prepared him. “You’re being as thorough as possible as you try to kill me,” he said, according to the account of Troy Hayden, a news anchor with Fox 10. “You worship death, don’t you?”

His last words, just after the injection had begun, were: “Maybe I’ll see you on the other side, Deana. I don’t know you and I don’t remember you.”

Dixon and his attorneys spent the last several weeks appealing his execution, in state and in federal court. The team of lawyers has argued that Dixon’s history of mental illness should disqualify him from the death penalty. His attorneys, this week, pursued that argument all the way up to the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and then the U.S. Supreme Court. Relief was denied both times.

“Clarence Dixon has suffered from paranoid schizophrenia for decades and has delusions surrounding his upcoming execution,” wrote Eric Zuckerman, one of Dixon’s attorneys, in a statement this week. He argued an execution would violate the Eighth Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment.

The court disagreed, citing case law that says “delusions come in many shapes and sizes, and not all will interfere with the understanding that the Eighth Amendment requires,” and saying that Dixon’s illness and delusions did not meet such a standard.

When Dixon killed Bowdoin, the two were students at ASU, living in Tempe. She was his neighbor, though it was not clear if the two had ever interacted before the night of Bowdoin’s death.

Two days before he killed Bowdoin, in January 1978, Dixon was found clinically insane in a separate assault case against him, and found not guilty by reason of insanity. Although the Maricopa County Superior Court judge in that case directed Dixon to be committed to a hospital for treatment, Dixon was instead released unsupervised.

Though Dixon was not identified as a suspect in the Bowdoin case for another 20 years, he wound up with a life sentence for a sexual assault of a young woman several years later. He was in prison when detectives ran DNA evidence that had been recovered at the scene of Bowdoin’s death through a database that connected Dixon to the crime.

Through Dixon’s trial and many subsequent appeals, Bowdoin’s family pushed for the sentence to be carried out. Her parents have since passed away, but Bowdoin’s sister, Leslie James, has stayed closely involved with the case.

“There is not one legal, social, or moral imperative for recommending reprieve,” James told the state clemency board in an emotional address, as the board considered Dixon’s sentence.

The Arizona Board of Executive Clemency hears arguments in Clarence Dixon’s case.

Katya Schwenk

Letters from nearly a dozen other family members or friends of Bowdoin submitted to the state prior to the clemency hearing carried a similar sentiment. Through a public records request, Phoenix New Times obtained letters sent in favor and against the sentence for Dixon.

“The sadness and loss our family has felt has been devastating,” wrote Susan Martin, who identified herself as Bowdoin’s aunt. “I fully support the warrant of execution as a most appropriate (and long overdue) step in finding justice for Deana and for all of our family.” Another cousin wrote that while “I believe in mercy as much as I do in justice,” she supported the death penalty in Dixon’s case.

The Arizona clemency board sided with Bowdoin’s family and declined to recommend a commutation or pardon to the governor.

Attorneys for Dixon had challenged the makeup of the board, arguing that it was stacked with former cops – in violation of state law. A judge dismissed that case, however, based partly on his conclusion that law enforcement was not considered a profession.

In the two weeks since the clemency hearing, attorneys for Dixon filed a flurry of other challenges to his sentence in an effort to stay the execution.

One complaint by Dixon’s legal team found problems with the state’s preparation of pentobarbital, the lethal drug that was used to kill Dixon. The drug was expired, attorneys argued, because it had failed one of the stability tests conducted by the state’s pharmacist.

In a last-minute settlement reached this week, the court directed the state to prepare a new batch of pentobarbital, but did not delay the schedule.

During a hearing before the Ninth Circuit, less than 24 hours before Dixon was executed, attorneys for Dixon again attempted to sway the judges to halt the impending execution.

Dixon’s lawyers reiterated the argument they have pushed through the courts for years: Dixon’s history of mental illness, including a schizophrenia diagnosis, should disqualify him from execution.

A 2007 Supreme Court ruling in a case called Panetti v. Quarterman established that if a prisoner does not rationally understand the reason for their execution, they cannot be executed. In that case – which bears similarities to Dixon’s – a man named Scott Panetti, who suffered from schizophrenia, believed that a cabal of some kind was conspiring to execute him.

Though Panetti understood that he was to be executed, and he understood that the official reason for his execution was because of his conviction, the court ruled that this, alone, was not enough – given that he had further delusions about the rationale for the execution.

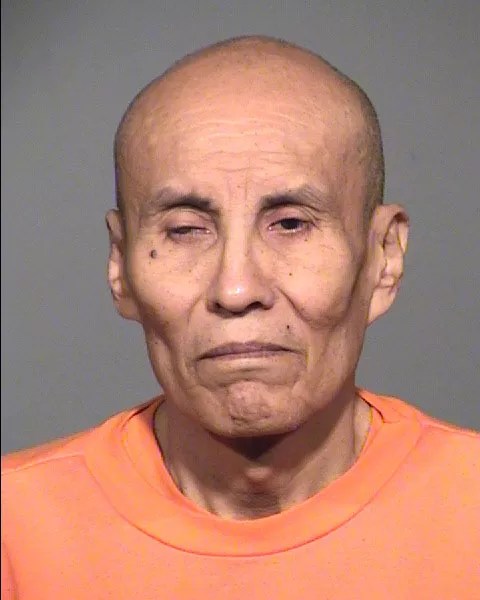

Clarence Dixon

Arizona Dept. of Corrections

Attorneys for Dixon made much the same argument in court on Tuesday. Dixon was diagnosed with schizophrenia multiple times over the years and suffered from hallucinations and paranoid thoughts.

Dixon became fixated on an obscure and meritless legal theory about his case, and believed, according to interviews with psychiatrists, that the judicial system conspired against him to execute him.

The Ninth Circuit judges were skeptical of Dixon’s attorneys’ claims. Just because he believed in such a conspiracy, argued Judge Forrest, “doesn’t mean he has delusions about why the execution has been ordered.”

The judges noted that, in the past, Dixon had brought up similar claims to the court. During his trial for the Bowdoin murder, Dixon represented himself. After the fact, his attorneys – including his defense lawyer at the time – questioned why he was allowed to waive a lawyer.

But in 2014, the Ninth Circuit agreed with the district court in Arizona’s findings that Dixon was, in fact, competent to stand trial at the time. His lawyers had not erred, the court found, by letting him represent himself at trial.

Once again, this argument failed to spare him.

The last time Arizona put a man to death, it was badly botched. In 2014, Joseph Wood lay on the gurney, alive, for two hours, while he was injected more than a dozen times with lethal drugs. Legal challenges to the state’s program following Wood’s death put a halt to the program, temporarily.

But Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, who assumed office in 2015, has promised for years to bring back executions.

Dixon’s death likely won’t be the last this year. On May 3, the state issued a death warrant for another man on death row, Frank Atwood. He has less than a month left to live.