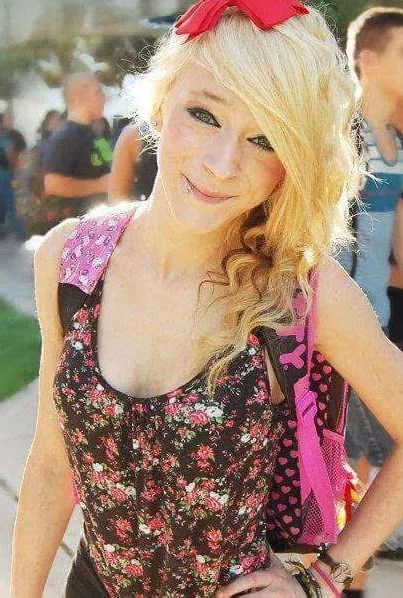

Photo courtesy of Nelson family

Audio By Carbonatix

On March 27, Chelsee Dennis walked into the office at the Franklin Phonetic Primary School in Sunnyslope, where her little girl attended classes. She was shaking. Her boyfriend was waiting in her car, Dennis told staff, and she needed help.

“She was terrified,” school principal Cindy Franklin told Phoenix New Times in a phone interview. “She told our secretary that her boyfriend would not leave her alone and she was afraid for her life.”

Police were called that day – twice – and, eventually, Dennis’ boyfriend was led away in handcuffs. Three weeks later, Dennis was dead. She was 29 years old.

Authorities have charged 36-year-old Dwight Miles with two counts of first-degree murder in the shooting deaths of Dennis and the couple’s unborn child. But the case raises uncomfortable questions about whether Phoenix city prosecutors have let another killer slip through their fingers.

Miles is at least the second man in less than two years to have gone through the Phoenix Municipal Court system charged with domestic violence, only to have the charges reduced or dropped – and then return to the dock later as a murder defendant, a New Times analysis of public records reveals.

In September 2016, Phoenix city prosecutors dropped misdemeanor assault charges against Kodi Bowe stemming from an attack on his girlfriend, Taylorlyn Nelson, court records show. The following summer, Nelson’s partially dismembered body was found at the bottom of Lake Pleasant. Bowe and his relatives are charged with her murder.

One week before authorities found Nelson’s body, a third homicide occurred – this time while the accused was awaiting trial on two separate domestic violence charges in Phoenix Municipal Court, records show. In May and June 2017, Phoenix city prosecutors filed two misdemeanor assault charges against Ignacio Estrada, then 19, court records show. City records show he skipped two hearings and two bench warrants were issued for him.

In July, Estrada was charged with first-degree murder in the death of his younger sister, 15-year-old Reyna Estrada. Authorities say he put a loaded shotgun to Reyna’s head and pulled the trigger. He is accused of trying to kill his parents, too; their lives were spared by a “malfunctioning” firearm, authorities claim.

An Arizona law on the books since 2015 requires judges to assess a defendant’s risk of domestic violence, regardless of how they’re charged in a given case. Phoenix city prosecutors declined to discuss either the Estrada or Miles cases (citing still-pending misdemeanor charges) and they seemed to have a tough time making up their mind about the Bowe case.

On the one hand, city spokeswoman Julie Watters claimed that Taylorlyn Nelson “did not desire prosecution, and Bowe did not have a violent criminal history in our system at the time of his arrest.”

On the other hand, Watters said prosecutors were so stunned after “learning of the horrific subsequent acts” in the Bowe case that they overhauled their entire charging process to prevent something like it from happening again.

How, then, did Miles – with his long list of felonies and his prison record – slip through the cracks? Again, Phoenix city officials went mum, and declined our requests to interview agency head Vicky Hill and BeBe Parascadola, the lead prosecutor on the Bowe and Miles misdemeanor cases.

“We are unable to provide a comment on why Ms. Parascandola reduced the charges,” spokesman Nickolas Valenzuela said in a statement, noting that it could hurt the defendant’s chance at a fair trial.

Taylorlyn Nelson

Photo courtesy of Nelson family

The names Chelsee Dennis, Taylorlyn Nelson, and Reyna Estrada are part of a macabre roll call that has made Arizona one of the worst states in the nation for domestic violence:

• A 2017 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta estimated that 38.6 percent of people in Arizona had been subject to domestic abuse; that was third in the country, behind only Kentucky (42.1 percent) and Nevada (38.7 percent).

• In the five years between 2012 and 2017, some 667 people were killed in domestic violence-related incidents, according to statistics kept by the Arizona Coalition to End Sexual & Domestic Violence.

• Arizona ranks eighth in the nation for female homicides, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

“Arizona has always been in the top 10 for women killed by intimate partners,” Arizona Coalition to End Sexual & Domestic Violence CEO Allie Bones told New Times. “Part of the issue in Arizona is, I mean, we have a Wild West mentality. A lot of people say that and throw it around as an excuse.”

Bones and her colleagues assemble their data on domestic violence homicides from press clippings. (The group used to have someone sit on local jurisdictions’ fatality review committees, but the work was too much for one person, Bones said.) They count incidents where people die at the hands of police and they add those who turn their weapons on themselves to the list. Still, Bones says, the list is probably an underestimate of the actual carnage.

Bones says she doesn’t doubt authorities’ sincerity or willingness to take domestic violence seriously, but she adds that the “Wild West” mentality can make it hard to get them to focus on the essentials – such as confiscating firearms from those accused of domestic violence.

“The mechanisms to ensure that law enforcement or the courts make sure that the guns are relinquished are just not there,” Bones says. “We have leaders who are all A-rated from the NRA and they’re proud of that.”

Arizona’s domestic violence gun homicide rate is 45 percent higher than the rest of the nation, according to the CDC’s analysis.

(In fairness to local law enforcement, Miles didn’t have a firearm to confiscate when he was accused of attacking Dennis at Franklin school on March 27; authorities claim that he illegally bought the fatal pistol on Phoenix’s streets, for around $250. It’s unclear where the shotgun that killed Reyna Estrada came from.)

It has taken years to acquire a kind of grim expertise on domestic violence.

One of the things experts will tell you is that for most, the violence is only a late-stage manifestation of a pathology of control: The abuse often begins with subtle hints – your friends make him uncomfortable, say, or questions like, “Are you really going to wear that?” or seemingly generous offers to run the finances so you don’t have to worry your pretty little head about it. By the time he (or, yes, she) raises a hand against a lover, they’re striking someone who may well have been mentally broken a long time ago, experts say.

“Usually the violence is a form of escalation because the other controlling mechanisms haven’t worked,” said Chris Groninger, chief strategy officer of the Arizona Bar Foundation, which provides funds for pro bono civil representation to the victims of domestic violence. “It doesn’t always show itself or present itself on the first encounter. It can be very subtle, very kind of easy to dismiss to as protective and loving and caring.”

“We have a significant problem here,” Groninger said of Arizona.

Franklin Phonetic Primary School Principal Cindy Franklin and teacher Tom Franklin say they witnessed the assault on school parent Chelsee Dennis.

Tim Vasquez

As she sat shaking in the principal’s office of the Franklin school on March 27, Chelsee Dennis described a life that most domestic violence experts would easily if painfully recognize.

“She wanted to get out of the house and he hadn’t made that possible because it was almost like he was holding her prisoner,” said Tom Franklin, Cindy’s husband. “She couldn’t shut the bathroom door because he was all paranoid. She didn’t have a house key or anything.”

Cindy Franklin said she went to Dennis’ car, where Miles was waiting, and told him to leave. When he didn’t, Franklin asked school secretary Nida Luna to call the Phoenix police. Officers responded and told Miles to leave or face arrest. He walked off, the Franklins recalled, but then so did the cops.

As Dennis drove off from the Franklin school, “our secretary started screaming, ‘He’s running across the street,'” Tom Franklin said. Tom Franklin, a second-grade teacher who didn’t want his name used, and teacher’s aide Francisco Lopez ran outside to help.

Miles’ lips were chalk white, Tom Franklin said. He was raving, “We’ve gotta get out of here,” and trying to snatch the car keys from Dennis. He was pawing “like a lion or a bear,” Tom Franklin said.

The second-grade teacher and Lopez wrestled Miles onthe passenger side, and Tom Franklin opened the driver’s door so Dennis could escape. The trio of school staffers then slammed the car’s doors, pinning Miles inside the car, Tom Franklin said.

Inside, Luna, the school secretary, had called 911 again, and the Phoenix cops came rushing back. They cuffed Miles, but, Tom Franklin said, they didn’t seem to consider the incident all that big of a deal.

The second-grade teacher kept urging the officers to write the case up as an attempted kidnapping, to have Miles tested for drugs – anything that might warrant a felony charge and put Miles away for a bit, Tom Franklin said.

Miles was charged with three misdemeanors and was back on the streets within hours. (Cindy Franklin said she had obtained a restraining order to keep Miles off school grounds and tried to serve him with it at the lock up that evening; he had already been released.)

“They just didn’t take it seriously,” Tom Franklin said. “It’s just another day in Sunnyslope, I guess.”

Phoenix Police spokesman Sergeant Jonathan Howard declined to comment for this story.

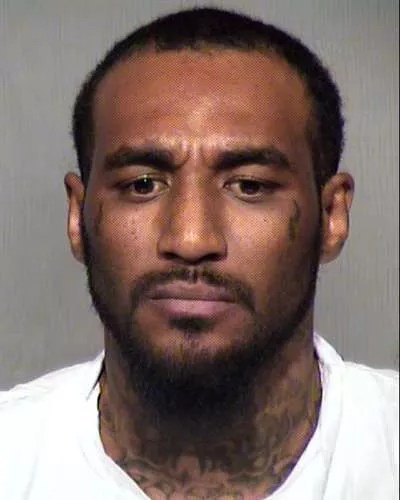

Misdemeanor assault charges were dropped against Kodi Bowe, now accused of murdering Taylorlyn Nelson.

Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office

Bones, the Arizona Coalition leader, said she can empathize with law enforcement officials who stand helpless before the merciless patterns of domestic violence. It’s hard for victims to break free; they’re often reluctant witnesses and cases fall apart. Any cop or prosecutor might want to throw her hands in the air, Bones said.

“They see the same victims, over and over again, and get frustrated,” she said.

It’s easy to see how prosecutors’ offices such as Phoenix City can get overwhelmed. In fiscal year 2016, the Phoenix Municipal Court saw more than 13,000 petitions filed for orders of protection and another 6,700 petitions to protect against harassment, according to state records. Each figure was down slightly from the year before.

Even orders of protection aren’t a guarantee of safety: In 2016, at least two domestic violence homicides – the June 17 stabbing death of Maria Rivera, 48, in Phoenix, and the July 23 beating death of Eileen Yellen, 60, of Ahwatukee – had histories of protection orders, the Arizona Coalition’s annual report states. (Yellen’s presumed killer, Cathleen Baker, 48, had also taken out an order of protection against Yellen; Baker killed herself shortly after Yellen died.)

Just because authorities feel overwhelmed, though, it isn’t an excuse to surrender, the Bar Foundation’s Groninger said. In fact, not prosecuting domestic violence often plays right into the abuser’s hands, she said.

“It’s easy to believe your abuser who might say, ‘No one’s going to believe you, they’re going to take your kids away,'” Groninger said. “When the system also collaborates with that thought it makes it all the easier to believe it.”

For authorities, it’s essential to remain focused, Groninger said: “The question is, ‘Why is he hitting someone?’ not, ‘Why is she staying?'”

Assault charges against Dwight Miles were reduced before the death of his girlfriend, Chelsee Dennis.

Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office

Three years ago, in an effort to come to grips with its domestic violence epidemic, Arizona became one of the first states in the union to require judges to use some kind of domestic violence risk assessment when considering a defendant’s bail conditions – even if the defendant hasn’t actually been charged with domestic violence. It’s a brave step, but the crisis is still bigger than the criminal justice system itself, said Neil Websdale, director of the Family Violence Institute at Northern Arizona University.

“The judicial system is not well equipped, in many ways, to deal with parties who come to the court not as free-standing adversaries, but as partners in a relationship where there’s a power imbalance,” Websdale said of domestic violence’s victims. “You’ve got to remember, there are a lot of these cases going through the system. And we have a system that emphasizes the rule of law and due process and we have to keep those at the forefront of what we do.”

Websdale has helped develop APRAIS, a risk assessment tool endorsed late last year by the Arizona Supreme Court. It’s already in use in Phoenix. Websdale is confident that it can help cops, prosecutors and judges do a better job of recognizing the pathology of domestic violence and to reach out to victims but ultimately, he said, any risk assessment depends on victims being willing to ask for help.

“It’s very easy for folks on the outside to say, ‘Well, the system is uncaring or the individual police officers don’t give a shit about victims at the scene,'” Websdale said. “But it’s so much more complicated than that. Basically, these are community problems. And until we create a shared language of risk that recognizes the community-based inputs to those risks, we’re going to have these problems.”

Websdale is saying more for the Phoenix City prosecutor’s office than it will say for itself. New Times has filed a request, under Arizona’s open records laws, for materials related to the handling of the Bowe, Estrada and Miles domestic violence cases; the city hasn’t yet responded.

After his arrest at the Franklin school on March 27, Dwight Miles was charged with three misdemeanors, including assault. For reasons that remain unclear, prosecutors knocked it all down to a single count third-degree trespass and let him walk out the door, records show. The reduced misdemeanor charges formally entered the record on April 18 – the day after Chelsee Dennis died.

She leaves behind a 5-year-old girl who watched her mother die and who, authorities allege, had to beg for her own life.

Cindy Franklin, the school principal who tried to help Dennis, said she is just angry.

“Chelsee and her little girl came to school for the rest of that week and then she said she was going to California. And we rejoiced because we thought we had rescued this woman from an abusive man,” Cindy Franklin said.

“Until we heard the news.”

Bill Myers is a freelance reporter. Email him at myers101@outlook.com. He tweets from @billcaphill.

CORRECTION: New Times initially reported that Ignacio Estrada had last appeared in misdemeanor court on July 7, a week before he was charged with murder. In fact, he skipped two separate hearings in June and there were two bench warrants issued for him. He did not appear in court again until he was arrested on murder charges.