Hannah Critchfield

Audio By Carbonatix

The young family from Mexico sat on the wooden benches of the Tucson migrant shelter, cups of chicken soup in hand, as Dr. Timothy Domer ran down the list of questions.

They had spent nine months waiting at the border and several days in Border Patrol detention before being transferred to the Casa Alitas shelter by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The family members wore a somewhat bewildered look as a flurry of doctors greeted other families with gusto and the same questionnaire.

Dr. Domer found that the family of the five reported no dizziness, no fevers, and no pregnancies.

But then he asked:

“Are any of you experiencing any abdominal pain?”

The mother and daughter pointed to Javier, who was 9 and looking slightly pale, clutching his soup.

“He ate the burrito,” his mother said through a Spanish-English translator.

The experience observed by Phoenix New Times was reportedly a typical scene at the shelter.

Doctors treating migrants after their release from Border Patrol custody say that a disproportionate number of their patients feel ill after eating the food the federal agency gives them – namely, a certain packaged burrito.

“I would say within every family there’s at least one person who either says they feel sick after eating the burrito, or they couldn’t eat because the food’s so bad,” said Domer, a geriatrician who sees asylum-seekers weekly at Casa Alitas. “If I had to put a percentage on everybody that we see, it would probably be greater than 50 percent.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which oversees U.S. Border Patrol, said it’s investigating the situation following Phoenix New Times’ report of these concerns.

“We want to take care of people,” said Meredith Mingledorff, spokesperson for CBP. “We always want people who experience inappropriate behavior from our personnel to address it, and we take every allegation seriously.”

A Food-Based Illness?

Casa Alitas, a short-term shelter for asylum-seekers run by Catholic Charities in Tucson, has served hundreds of families seeking asylum in the last year. Through an agreement with the federal government, the shelter receives migrants directly from immigration enforcement, providing pro-bono aid before the families move on to the next step of their journey – meeting up with a sponsor, usually a family member or an organization, who they’ll stay with while their claim works its way through immigration court.

Through this role, the shelter’s volunteer doctors are among the first people to interact with migrants after their time in Tucson Border Patrol custody, conducting medical screenings to assess asylum-seeking families’ health upon intake. They told New Times they’ve been hearing reports of migrants getting sick after eating the burrito since their first days at the shelter.

Casa Alitas shelter in Tucson, which receives asylum-seekers directly from immigration enforcement.

Hannah Critchfield

“Probably a quarter of the families that come through have some gastrointestinal complaints that they associate with the food, because it started when they were in detention,” said Stephen D. Thompson, MD, a retired pediatrician and anesthesiologist. “And some days, it seems that it’s more than that.”

Though Casa Alitas technically receives the families through ICE, according to Teresa Cavendish, director of Casa Alitas, these asylum-seekers have only been placed in ICE’s care that morning. The food they describe eating, particularly the burritos, which are the only hot meal the Tucson Border Patrol provides, comes from their time in a Tucson Border Patrol detention facility.

In the Tucson Sector, an average asylum-seeking family stays about three to four days in custody at one of the Border Patrol’s eight temporary detention facilities. During this time, family members are fed three hot meals a day – but the only guaranteed food in those meals is a prepacked, frozen burrito, which is reheated and served to migrants awaiting release to a shelter like Casa Alitas or relocation to an ICE detention center, according to the agency’s past statements in court documents, Casa Alitas doctors, and Mingledorff.

The sickness usually goes away after a few hours at the shelter, the doctors said, particularly after eating other food the shelter provides, like chicken soup and watermelon.

Doctors said they believe the illness is not due to a general shock of food to the system after migration to the U.S.-Mexico border, in which migrants may consume less food than usual, but rather due to the food given by the Border Patrol itself.

New Times witnessed three of these medical screenings on two separate visits, one prearranged and one unannounced. Two families reported that at least one member experiencing “burrito sickness.” The adult mother of another family said she opted not to eat because she found the food inedible.

“I would say that, without exception, within every family, there’s people that haven’t eaten because of the food,” Domer said. “And sometimes entire families haven’t.”

Of those who do eat the burrito – doctors said many of the consumers are children, who are less likely to turn down food – Domer estimated about 80 percent of migrants express feeling abdominal or stomach pain.

“It’s great that camera crews want to come here and see the happy stuff, and the work that we’re doing here,” Domer said, noting the frequency of media visits to the Tucson shelter. “But the real story is what’s happening before asylum-seekers come to us. That’s where people should be looking.”

Bad Burritos, or Bad Preparation?

Border Patrol sectors usually source their food locally – in the Tucson facilities where migrants are held, the burritos come from a company called Malone Meat and Poultry, a Tucson-based supplier.

Malone Meat and Poultry is the only food supplier that has a contract with Customs and Border Protection in the Tucson Sector – the federal government awarded them a total of $1,005,000 last year for things like “frozen specialty food manufacturing” and “detainee meals,” according to USAspending.gov.

The manager of Malone declined to comment for this piece, but Mingledorff of CBP confirmed that company is the source of the burritos all migrants held within the Tucson Sector are fed. By the end of 2020, the Department of Homeland Security will have paid them an additional $730,169 to continue this partnership.

But doctors who volunteer at Casa Alitas said it may be the way the burritos are prepared by Border Patrol staff, rather than the quality of the food itself, that’s leading to illness.

“From what people say, I think it’s mostly because they’re not prepared well – they’re still frozen or cold,” Dr. Thompson said.

“It’s inadequate heating,” another doctor at Casa Alitas, Dr. Susan Thompson, an internal medicine and anesthesiology specialist, said based on reports from migrant patients. “And who knows where they’re storing them once they’re thawed?”

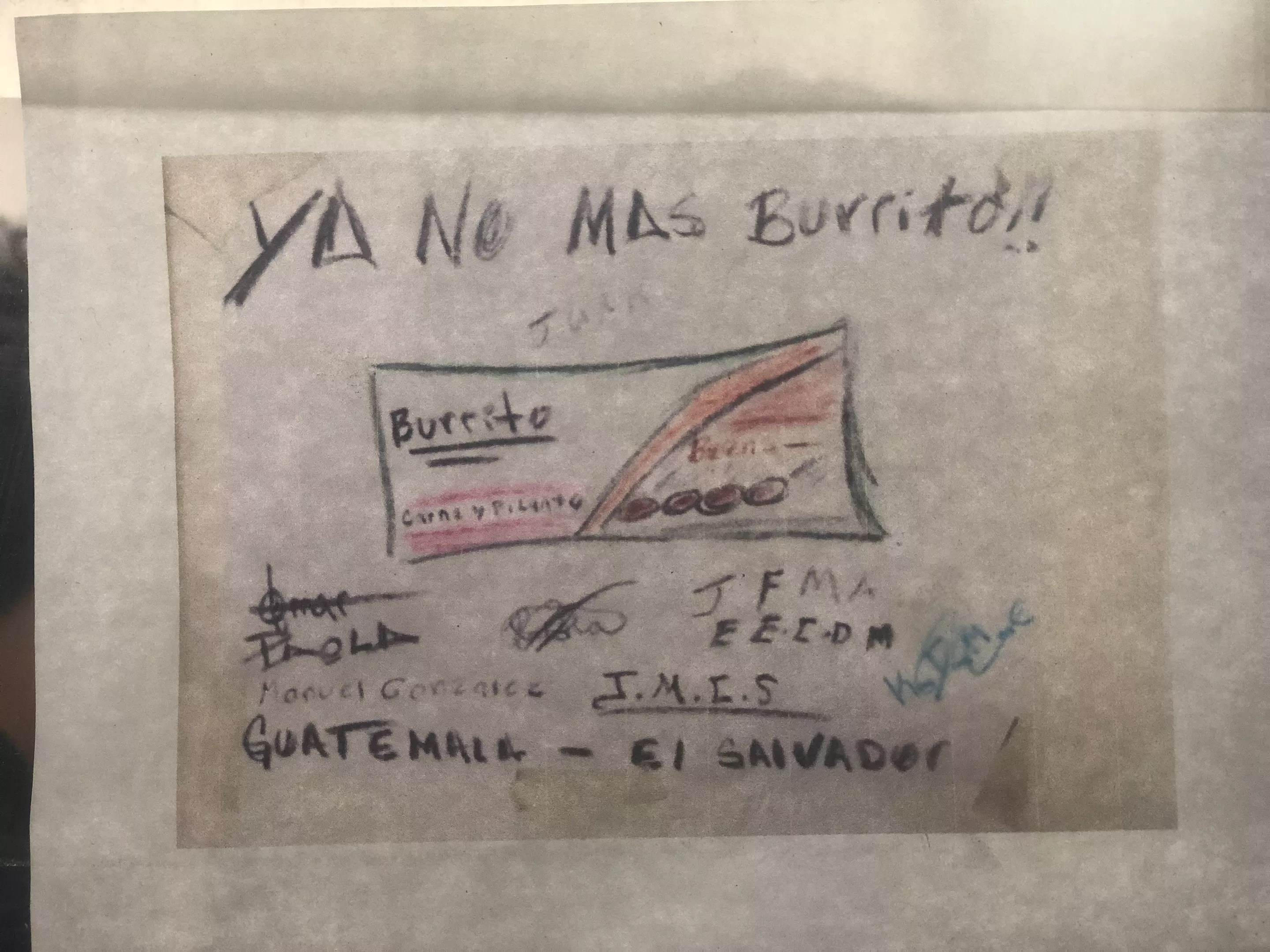

Cavendish, the director of Casa Alitas, confirmed that staff members frequently hear negative reports about the burritos. The phrase, “No more burritos!” is often uttered by the staff to incoming asylum-seekers

“The thing is, they have a warmer specifically for burritos – they love that burrito warmer,” Cavendish said, referring to the Border Patrol’s Tucson Processing Center, the sector’s largest station. “They’re really proud of it. They’ll show it off to you if they ever let you visit.”

Border Patrol in the Tucson Sector has not yet granted New Times’ requests (first made in July 2019) to visit the Tucson Station.

“If agents aren’t heating food properly, that’s something we need to fix,” said Mingledorff of CBP. “There shouldn’t be any excuse for that. If it has happened, I personally apologize and offer to those who have come through our facilities my respect and promise that we will work to make things better.”

A History of Complaints

In 2015, a group of legal organizations filed a lawsuit against the federal government, alleging that U.S. Border Patrol in the Tucson Sector holds its adult and children detainees in unlivable, unconstitutional conditions.

A portion of the ongoing lawsuit, Doe v. Wolf, based on interviews with 75 former detainees, dealt specifically with the food the agency provided.

“The food is often of such poor quality that detainees are unable to eat it, or report feelings of nausea and stomach pain after trying to eat it,” states the original complaint, filed by the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, the National Immigration Law Center, the American Immigration Council, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area, and Morrison & Foerster LLP.

According to subsequent court documents submitted by CBP, the food then consisted of the same diet of burritos, crackers, and juice still provided within facilities today.

Filed during the Obama administration’s tenure, the lawsuit remains the only systemic legal challenge to the standards of care provided within the Border Patrol’s temporary holding facilities.

In 2016, the judge overseeing the case issued a temporary injunction ordering Tucson Border Patrol to remedy certain conditions immediately, including providing mats for detainees held for longer than 12 hours and guaranteeing access to clean water.

But the quality of food distributed by Border Patrol remains up for debate.

“Prison food does not need to be tasty or aesthetically pleasing, it must simply be adequate to maintain health,” wrote U.S. District Court Judge David C. Bury in the injunction. But since the injunction, Bury has allowed plaintiffs to monitor food conditions within Tucson Sector Border Patrol facilities ahead of the trial.

Under Customs and Border Protection’s National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS), introduced in 2015, food provided to detainees must be in an “edible condition” – specifically, not frozen or spoiled.

Whether or not Customs and Border Protection is meeting those standards will be a primary focus of the trial for the case, which began on Monday.

“Broadly speaking, we continue to hear that there are issues with meals,” said Victoria López, legal director of ACLU of Arizona. “A lot of the case, from our view, will be about getting the court to make permanent what’s in the injunction, and determining what’s required of CBP when it comes to all of these things that frankly, we’re still seeing in Border Patrol jails.”

Much of the plaintiffs’ findings from monitoring of food conditions, which were previously confidential under the protective order, are expected to come out over the course of the two-week proceedings.

(Correction: The original story mistakenly identified Dr. Stephen Thompson with another MD of the same name.)