Audio By Carbonatix

Before a natural disaster hits, what do you do? You run to the store and load up on food, water, and batteries, of course.

Something similar is happening in central Arizona with water as a serious drought looms on the horizon.

In recent years, cities, municipalities, tribes, and industries have been upping their orders from the Central Arizona Project, which is responsible for transporting water through 336 miles of pipelines and canals from Lake Mead on the Colorado River to Maricopa, Pima, and Pinal counties.

Arizona cities are using the larger orders to stockpile water ahead of potential future cuts, which are being negotiated as part of Arizona’s Drought Contingency Plan (DCP).

“We’ve known for several years that DCP was potentially coming, and we were going to face potential shortages and cuts,” said Cynthia Campbell, water advisor for the city of Phoenix. Ordering more water in order to store it has “primarily been to make sure that we have resiliency in the face of potential shortage.”

Since 2015, the drought has been described as “imminent,” Campbell said. “The projections just get worse all the time. We’re trying to do what we consider to be the prudent thing.”

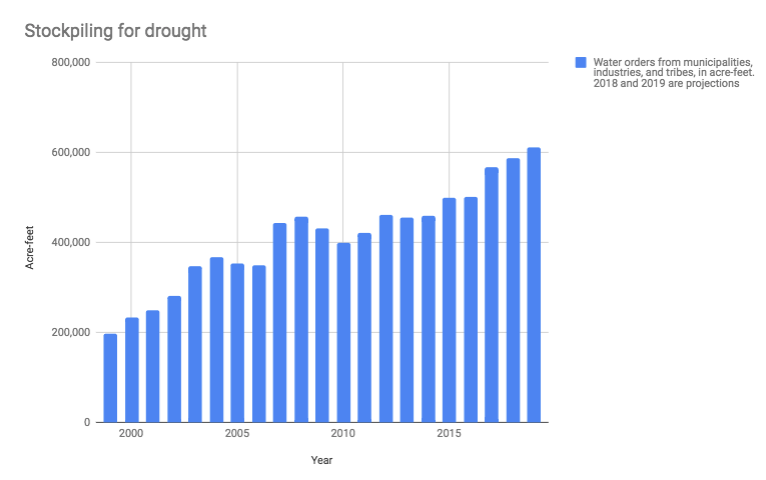

The latest numbers, presented November 1 at the CAP board meeting, show that Arizona cities and industries ordered 610,825 acre-feet of water in 2019, up from 587,324 acre-feet in 2018, even as CAP’s supply of water decreased slightly.

An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons, or about half an Olympic swimming pool’s worth of water.

Those numbers fit an ongoing trend of increasing water orders. In 2017, the state’s municipalities and industrial users ordered just under 568,000 acre-feet; in 2016, they bought roughly 501,000. Orders placed under these contracts sometimes differ from the amount actually delivered. In 2016, CAP delivered about 511,000 acre-feet of water, for example. The year before, it delivered about 600 acre-feet more than ordered.

Source: Central Arizona Project water order and delivery reports.

Elizabeth Whitman/Phoenix New Times

The federal Bureau of Reclamation currently gives the reservoir Lake Mead, which sits on the Colorado River, a 57 percent chance of entering a Tier 1 drought in 2020. That designation kicks in if Lake Mead’s level drops below 1,075 feet above sea level. As of Friday, lake levels stood 3.5 feet above that.

For the third year in a row, Phoenix has ordered its full allocation of Colorado River water – 186,557 acre-feet per year, according to Campbell.

Those numbers cannot be explained by growing consumer demand. “Demand has been fairly flat over the past, at least since the recession, if not before,” said Campbell.

Even as the population grew, water consumption in Phoenix dropped sharply from around 345,000 acre-feet in 2007 to about 310,000 acre-feet in 2008. It rose and fell for the next few years, ending around 300,000 acre-feet in 2014, the last year available from City of Phoenix data.

The Colorado River is not Phoenix’s sole supply of water. It also draws from the Salt River Project, groundwater from the city’s wells, and reclaimed, i.e. recycled, water.

The city now stores about 58,000 acre-feet, or just under one-third of its annual CAP allocation, underground. Water banking, as the process is known, can be done by actively injecting water through wells and into aquifers underground. Phoenix owns several such wells in the northern part of the city.

Water can be allowed to seep into the ground, as is done at the Southern Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project. Enormous basins, several football fields large, sit over ancient stream beds known as paleochannels, allowing water to travel underground.

The water recharge basins of the Southern Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project.

Phoenix didn’t always bank so much water. One reason is that the need wasn’t great because of the city’s diverse water portfolio, and because it has priority status to water from Salt River Project. But Phoenix also didn’t always have an easy place to bank the water.

That started to change about four years ago, when drought warnings grew more frequent and more dire. Recently, the city has inked deals with the city of Tucson and the Salt River Project to store water in facilities owned by those entities.

In late September, SRP and Phoenix announced a deal that would allow Phoenix to store additional unused Colorado River water in the Granite Reef Underground Storage Project, which sits on Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community land.

“This partnership with SRP is a smart and creative plan to safeguard against continued drought and will allow us to use our stored water supply in future times of shortage,” Phoenix Interim Mayor Thelda Williams said in a statement at the time.

Besides Phoenix, other municipalities in Maricopa County have also been banking water, said Warren Tenney, director of the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association, whose members include Peoria, Scottsdale, Tempe, Mesa, and others. Cities in southern Arizona, including Tucson, are doing it, too.

“All of the cities are in the process of storing water, because that’s smart planning,” Tenney said. “They all recognize that lean times are ahead, and so it’s important to maximize the use of their water. That includes being able to store it for the future.”

Patrick Dent, water control manager for the Central Arizona Project, said that the city of Tucson was responsible for the single largest change in the additional 23,500 acre-feet of water that cities and industries ordered in 2019 from CAP.

At the same time, CAP’s estimated supply of water from the Colorado River declined, from 1.648 million acre-feet in 2018 to 1.595 million acre-feet in 2019, he said. Part of this has to do with the ongoing drought negotiations, which stakeholders are supposed to agree upon by the end of November.

“We are setting some aside for potential mitigation per the DCP negotiations,” Dent told the CAP board Thursday.

In 2018, the Central Arizona Project made 43,000 acre-feet of water available from Lake Pleasant, into which it pumps water during the fall and winter and from which it releases water in the spring and summer.

“In 2019, there’s not as much water going into Lake Pleasant,” Dent said.