Tom Carlson

Audio By Carbonatix

Other than the battering ram and firearms, the nine members of the Maricopa County drug unit who arrived at Clay Villanueva’s Phoenix home on the morning of May 19, 2020, cut a casual profile. They wore beige T-shirts that read “HIDTA,” the federal narcotics task force they represented. One sported a backwards baseball cap.

“Why are you here?” a neighbor asked as they approached the pastor’s home. According to court testimony, they responded “gaily, voices joined in sing-song: ‘We’re here to serve a search warrant.'”

The detectives pounded on the door and Villanueva opened it. The pastor stood before them in his underwear looking a little gaunt, though at that point he’d not yet been diagnosed with cancer. His wife, Cecilia, appeared behind him. Moments later, they were both sitting in their front yard, handcuffed and half-naked, as they were read their Miranda rights.

The detectives had come to the house looking for a drug lab. At that time, lead detective Matthew Shay’s working theory was that Villanueva and Cecilia were manufacturing DMT in their home, chemically extracting the powerful hallucinogen and then distributing it.

Shay was a clandestine lab specialist with a 20-year tenure at the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, and he had emphasized that experience in order to obtain the search warrant. In truth, there was scant evidence of such a lab’s existence, aside from a single vague tip that the DEA had received back in January.

But Villanueva seemed eager to talk, in hopes of clearing things up. He explained to Shay what the detective already knew: The pastor led a small religious practice in Phoenix called the Vine of Light Church. Each month, its guests would congregate and take ayahuasca, a psychoactive brew that contains a small amount of DMT. The two-day ceremony required a payment from each guest of $360. But this was a religious practice, Villanueva explained. His church was involved in an ongoing legal battle with the DEA over whether to allow churches like Vine of Light to possess their sacrament legally. And he wasn’t manufacturing the drug, anyway; he was just importing it up from Peru.

Shay, Villanueva later recalled, was “warm and understanding” as they spoke. The detective assured the pastor that it was apparent that he was no drug dealer. Villanueva relaxed.

Inside, though, the agents were combing the place. In the pastor’s small office, they found a dozen bottles of a brown liquid, which Villanueva told them was ayahuasca. The agents kept going. They found a small amount of psilocybin mushrooms. Two pounds of marijuana. In a secret compartment behind an air conditioning vent, substantially more ayahuasca: 85 pounds of the drug. Inside a hanging shoe rack, more than $14,000 in cash. In a shed outside, a cannabis grow. As the raid stretched on, Villanueva began playing a “flute type of instrument,” Shay later recounted.

The detectives seized the drugs and the cash. But authorities did not arrest Villanueva that day, and no charges were filed. It would be another 18 months before the pastor’s legal trouble began in earnest, and before he realized that Maricopa County believed him to be a drug kingpin.

Clay Villanueva.

Pablo Robles

The legality of ayahuasca in the United States is murky. DMT, its active ingredient, is a Schedule I drug, illegal under federal law. But ayahuasca is not a pure form of DMT. It’s a brew, made by stewing the banisteriopsis caapi vine with other shrubs found in the Amazon basin. And unlike other, more popular hallucinogens, ayahuasca is primarily used for spiritual purposes, during shamanic ceremonies, a practice that originated in South America but in recent years has been globalized, imported to the U.S. and elsewhere.

In a landmark 2006 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the religious use of ayahuasca was legal; to prosecute a church for its use of ayahuasca, the court concluded, would violate congregants’ religious freedoms. That ruling stands. But the DEA has since created an opaque bureaucracy for religious exemptions to federal drug laws. The agency requires ayahuasca churches to complete an onerous application for an “exemption” from the agency. These applications are very rarely approved.

“People send these requests off and they just go into a black hole,” said Griffin Thorne, a corporate cannabis attorney in Los Angeles who has studied the issue. “Sometimes they get responses, and it’s always no.”

Churches like Villanueva’s exist in a legal limbo, unrecognized by the federal government and occasionally still prosecuted by it. But raids are rare enough that Villaneuva considered founding his church in 2017 a risk worth taking.

When Villanueva spoke with Phoenix New Times at his home in October, he sat with his feet propped on a stack of pillows to ease the swelling in his shins, a lingering side effect of the cancer treatment he’d received while in jail the month before. A police monitor hung around one bloated ankle. He’d let his beard grow long. It all gave him the aura of a martyr, though he spoke cheerfully, with a slight Southern accent and the blithe manner of an old stoner.

Villanueva discovered ayahuasca late in life, he said. But he had grown up on hallucinogens. He spent his childhood in rural Florida, a place called Plant City, noteworthy only for its winter berry farms – “mostly cows and strawberries,” as Villanueva recalled.

“Marijuana cost money, which we didn’t have,” he said. “But we had all the psychedelic mushrooms that we could eat.”

Psilocybin mushrooms grew out in the pastures, feeding off the manure and the sweltering heat. He and his friends would drive out and harvest them.

Villanueva was a teenager in those days – the early ’70s – still too young to drive. But the experiences shaped him, he said. He became disillusioned with the Christian church, taken in by the occult and the burgeoning psychedelic movement of the era. He left Florida to join the Navy, serving for seven years, working as a frogman and a sailor, occasionally landing in trouble for smoking pot. When he left the military, he bounced around a bit, settled in Phoenix, and found a modest career as a tech consultant – until one day, at the age of 50, when he felt called to jet out to the Peruvian jungle to try ayahuasca.

The drug was revelatory for Villanueva in a way that all the years of shrooms from the cow fields were not. “The universe just opened up,” he said. Over the next few years, he studied traditional shamanic ayahuasca ceremonies, returning again to Peru. By 2017, he was leading his own practice in Phoenix. He called it Vine of Light.

“That’s what ayahuasca is to me,” he explained. “It is the vine that carries the divine light. When you’re in the medicine, it doesn’t matter whether your eyes are open or shut. The illumination is just so fantastic.”

Over the years, Villanueva’s growing church attracted an eclectic congregation. Many of his attendees were troubled, seeking a kind of religious purging of whatever tormented them (quite literally; many who take ayahuasca vomit during the course of the ceremony). Some were veterans; some were domestic violence victims. They would all gather in a small, furnished shed at Villanueva’s home, ingest the ayahuasca in the evening, and trip through the night. Villanueva stood among them, singing Peruvian folk songs and banging a drum.

By most accounts, the ceremonies have had a positive impact. Veterans who worked with Villanueva told New Times that the experience eased their PTSD like nothing else had – claims supported by a growing body of research on ayahuasca as a treatment for trauma disorders. They trusted Villanueva, who was himself a Navy man.

“I met a lot of military people at Clay’s house,” said Richard Gaxiola, Villanueva’s former defense attorney. “Combat vets, you know.” Gaxiola, who has a reputation for representing some of Phoenix’s most odious lawbreakers, said several of his former clients were completely transformed after participating in Villanueva’s ceremonies.

Andres Ospina was recommended to Villanueva by his own psychotherapist. A former marine sniper and later Hells Angel (he was once profiled by New Times for his music ventures), Ospina first met Villanueva back in December 2019. Two days prior, on Christmas Day, a botched suicide attempt had sent him to the hospital. He was desperate, but he was also skeptical of Villaneva’s setup.

“It was a lot of hippie stuff, you know,” Ospina told New Times. “That’s not my thing. I’m not easily impressed.”

Ospina remains dismissive of the New Age element that attended the ceremonies – “I call them crystal-clutchers,” he said – but, hippie façade aside, Ospina swears that the church delivered him from the brink of suicide. “It was just so far beyond my ability to explain,” he said of the experience. “I couldn’t be left with any other feeling but that I had been in touch with something very old and very wise.”

After the May 2020 raid, Villanueva halted ceremonies, leaving his motley flock in pieces.

“Everybody scattered,” said George, another member of the congregation (a blackjack dealer turned corporate salesman, who asked, due to the ongoing prosecution, that New Times omit his last name). “It wrecked a lot of things and hurt a lot of people. Like, all in all, Clay was really doing something good for the world. Everybody was healing. He became this kind of person that people would confide in and seek out when they had nobody else.”

Sitting in the office where detectives had seized his drugs and cash, Villanueva gestured toward photos taken in Peru and queued up a video of an interview he’d given on the ceremonial use of ayahuasca. “We’re not a sham made up to distribute narcotics,” he said. “That’s not what we’re doing here. We’ve never sold anything. You can’t buy ayahuasca. It’s part of the ceremonial thing.”

Text messages that detectives lifted from Villanueva’s phone, though, complicate this picture. Dozens document sales of marijuana. Villanueva, though a licensed grower, was not authorized to sell. “Been out of flower a couple days now … hopefully we can meet early the earlier the better,” one person wrote to Villanueva, according to texts reproduced in the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office case file on the pastor.

Others show that, at least on some occasions, Villanueva was sending ayahuasca through the mail, to fellow shamans and, in one case, a customer who had requested a “high DMT brew.” The pastor might maintain that he only runs a church. But Maricopa County says it’s a business.

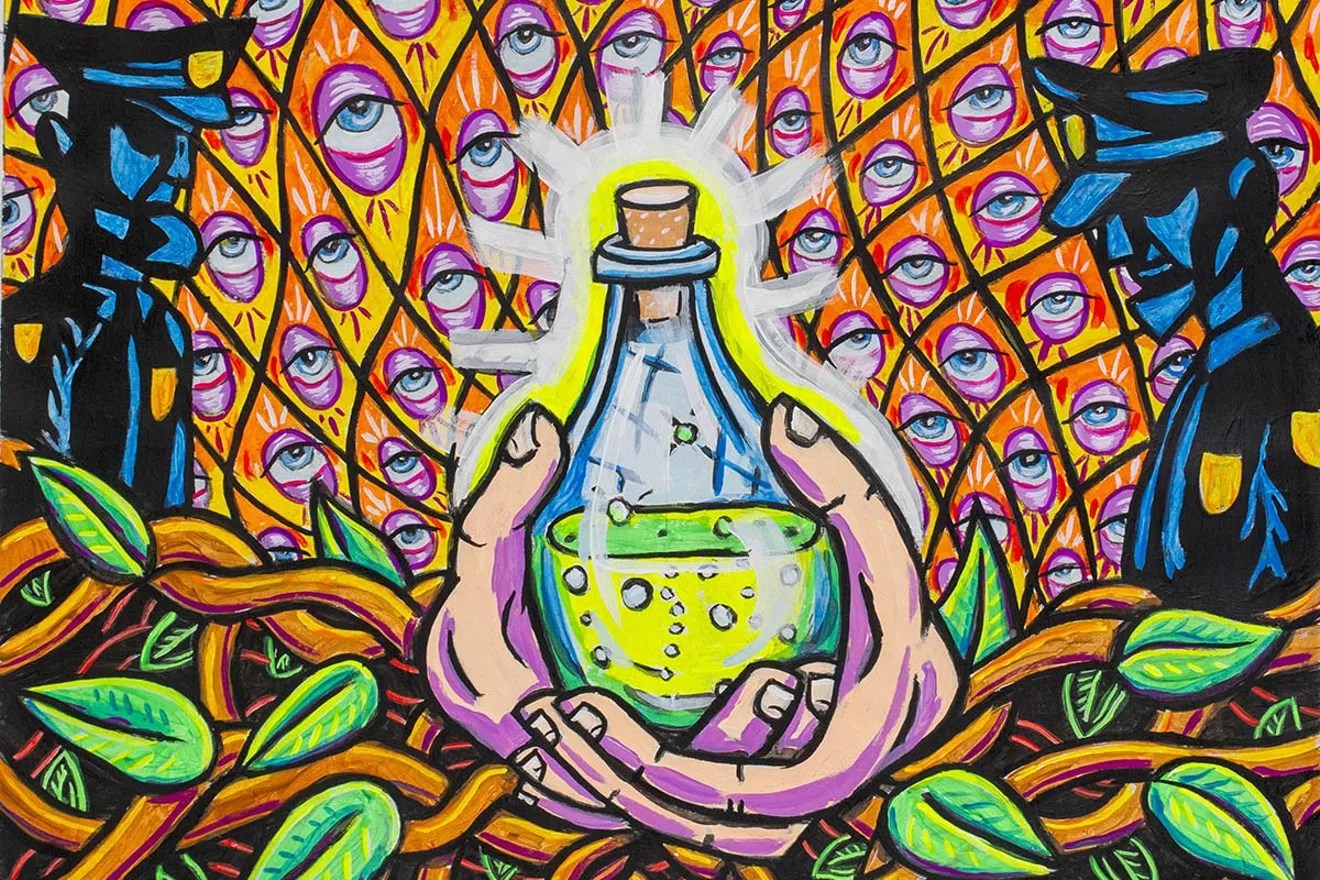

Banisteriopsis caapi, a vine from the Amazonian jungle, is brewed into a tea with other tropical plants to form the intense hallucinogen called ayahuasca.

Helder Faria/Moment/Getty Images

Charles Carreon was on the beach in Mexico in 2019 when he got a call from an ayahuasca church.

At the time, Carreon – a former prosecutor and disgraced cyberlawyer – had reached a low point. “I was just staring at the waves, not really knowing what I was going to do,” he recalled. “Sort of paddling along, circling the drain, as I suppose they say.”

He was still battling the fallout from a bizarre and frivolous legal campaign he’d waged, an ordeal that had spiraled into a lengthy and, for Carreon, embarrassing saga that would at one point earn him the title of “the internet’s most hated man.”

It began in 2012, when a popular online cartoonist, Matthew Inman, accused a website called FunnyJunk – by all accounts, correctly – of stealing and reposting his cartoons. The owners of FunnyJunk hired Carreon, at that time a lawyer of some renown, to represent them. Carreon sent back a long and somewhat unhinged letter to the cartoonist, demanding a $20,000 payout for defamation. In reply, the cartoonist drew a crude picture of Carreon’s mother seducing a Kodiak bear.

The bear cartoon touched a nerve. In the course of the legal battle that followed, Carreon personally sued the cartoonist, multiple anonymous online critics, the National Wildlife Federation, the American Cancer Society, then-California Attorney General Kamala Harris, and the fundraising platform Indiegogo, among other entities, under the vague stated purpose of upholding commercial fundraising laws. He also wrote a short song calling Inman “psycho-Santa.”

Nearly a decade later, Carreon is repentant of it all. “I had just become sort of a real asshole,” he told New Times. “So it was really not the worst thing in the world that a Reddit mob beat me up and caused me to reflect on what I was doing with my life. I literally stopped doing anything. I literally went broke.”

The ayahuasca church that had reached out to Carreon as he sat wallowing on the beach on that day in 2019 was the Arizona Yagé Assembly, a Tucson-based group led by Scott Stanley. Over the past year, the assembly’s ayahuasca had been seized multiple times by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Stanley, who said his congregation numbers are in the thousands, wanted to win legal status for his church. “What they are doing is treating a religious community like a drug cartel,” Stanley said of the feds.

Carreon, who grew up in Phoenix before moving to Tucson, had himself taken ayahuasca in the past and was sympathetic to the cause. He said he no longer attends ceremonies, though: “Not because I wouldn’t like to. It just seems like a good idea to keep your lawyer separate from your ceremony,” he clarified to New Times. It became clear, as he delved into the DEA’s policy, that obtaining an exemption from the agency would require a lawsuit.

Eventually, Carreon and Stanley would band together with Villanueva, and come up with a plan to challenge the DEA’s religious exemption practices in court. To do so, they formed an organization: the North American Association of Visionary Churches.

On May 5, 2020, not yet aware that one of its three founding members was under investigation by a federally-funded task force, the NAAVC filed suit, laying out its argument in a lengthy 80-page complaint. It argued that the DEA’s exemption process was illegal. It required churches to prove the sincerity of their religious beliefs to the drug agency, and then swear that they would not use any controlled substances until the exemption was approved . Often, they never were.

Twelve days after the complaint was filed, Villanueva’s home was raided. So launched the twin legal battles that would play out over the next year: Villanueva v. the DEA, and the State of Arizona v. Villanueva.

Despite the turmoil that would follow, the ayahuasca case lifted Carreon from his funk. “Now I can say, you know, that what I’m working on is fixing the problem that I encountered when I was 12 years old and I dropped acid,” Carreon said. “I thought, wow, this is fucking miraculous. And it’s illegal.”

The case against the DEA, originally filed in California, is now pending in U.S. District Court in Arizona. It has slowly become entwined with Villanueva’s case, which Carreon uses as evidence to show that ayahuasca churches, despite Supreme Court rulings in their favor, still suffer from prosecution.

“Clay is hanging on that precipice,” Carreon said of the pastor’s case. “The story that the authorities attempted to tell about him … It’s just false. It’s entirely false.”

Cecilia and Clay Villanueva.

Pablo Robles

Villanueva has advanced-stage lymphatic cancer. He has been battling it for more than a year. Distrustful of modern medicine, the pastor has selected a “completely naturopathic” method to treat it, he said, in lieu of chemotherapy or radiation. He keeps a restricted diet – “almost exclusively plant-based with a little bit of chicken” – and has traveled to Peru for spiritual treatments.

On August 22 of this year, Villanueva was again headed to Peru, for the purpose, he said, of treating his cancer and leading a group through ayahuasca ceremonies. He arrived at the Los Angeles airport with a ticket, carrying $10,099 in cash. He never made it on the plane.

Airport security had run a background check on Villanueva as the pastor proceeded through the airport. They found a warrant out for his arrest back in Arizona. He was detained at the gate and brought into custody.

Among other things, Villanueva’s arrest was a legal nightmare for his attorneys. Not only had the pastor been arrested in another jurisdiction, he was also – due to the fact that he was trying to leave the country with a large amount of cash – accused of being a “fugitive from justice.” He was held without bail.

The arrest was also a surprise. No one had known that Villanueva had a warrant.

Lawyers for Maricopa County and the federal agencies had spent the better part of the previous year maintaining that the pastor faced little risk of criminal prosecution. A judge had denied an injunction that would have protected him from prosecution due to the drug raid partially on that basis – all while, it now appeared, a secret grand jury in Maricopa County had been preparing an indictment for Villanueva on a slate of felony charges.

This infuriated Carreon.

“You can’t tell a federal judge that Mr. Villanueva’s fear of prosecution is ‘mere conjecture’ when there’s already, in the Maricopa County Superior Court, an indictment against Mr. Villanueva,” he fumed. “And you work for Maricopa County. You’re the lawyer for Maricopa County!”

The county was pursuing serious charges: A grand jury had indicted Villanueva on charges of conspiracy, money laundering, and multiple counts of felony drug possession. But for reasons that remain unclear, the warrant was never served, even though it had been issued two months before and the county was well aware of precisely where Villanueva lived.

As much as it might have appeared that Villanueva was attempting to flee the country, that does not seem to be the case. For months, according to plans posted on his website and in YouTube videos, he had intended to lead this trip to Peru in August. These were annual trips, which Villanueva had led for years. Videos on his website document them, and several participants confirmed to New Times that Villanueva had, indeed, brought them to the Peruvian jungle for ayahuasca ceremonies. He had even discussed these trips with the Maricopa County detectives during the raid, the year before.

The rest of the group proceeded to Peru, Villanueva said. But he was soon lost in the byzantine jail system of Los Angeles County. Carreon flew out to California to find him. When he did, the pastor was in poor shape.

“First words out of his mouth – ‘I am dying in here,'” Carreon recalled. “Well, I can see that, dude. I can see it.”

In jail, Villanueva could no longer follow his holistic diet, and his condition rapidly deteriorated. Complicating things was his rejection of typical cancer treatments, which meant that there was no doctor to vouch for his treatment program.

“He didn’t have any oncologist besides the fellow that diagnosed him,” Carreon said. “So I was tearing my hair out. Everyone’s got a goddamn doctor – except for useless no-count criminals who just got dumped there by county jail.”

Over the next several weeks, Villanueva was hospitalized twice. Carreon, meanwhile, was desperately trying to get him out of custody. But no one had the money. “He got $150,000 bail and cash bail. And cash bail means 150,000 dollarinos, and that’s that. And nobody had $150,000,” Carreon said.

After emergency petitions were filed in federal court, a judge eventually reduced Villanueva’s bail to bond, allowing him to leave with just an ankle monitor. But the charges remained. Even as he began to recover from his time in custody, they hung over him.

Villanueva in the Vine of Light Church with several “flute type of instruments.”

Pablo Robles

The story that the state of Arizona now tells about Villanueva is relatively straightforward.

Shay has admitted that the pastor was never manufacturing DMT; his clandestine lab theory was false. But, the state argues, that doesn’t matter. Detectives had seized more than four pounds of cannabis, a class four felony in Arizona. They had found psilocybin mushrooms and dozens of pounds of ayahuasca. And, furthermore, they had months of text messages that showed Villanueva dealing. It all amounted to nothing less than an “illegal drug enterprise.”

The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office declined to comment for this story, citing pending litigation. Spokespeople for the DEA did not reply to New Times‘ inquiries.

Over a year of court proceedings, Carreon has spun a story to counter this, spun in his signature fanciful style. It’s compelling, if wildly speculative.

It begins with the tip the DEA received on January 8, 2020, which initiated Maricopa County’s investigation into Villanueva. Special agent Marco Paddy, stationed at the DEA’s Phoenix office, received the call and passed the tip along to Maricopa County’s HIDTA task force unit, which works closely with the DEA.

The caller’s name is redacted from court documents filed by the DEA. But in various court declarations and an amended complaint in the case, Carreon laid out a theory that this tip – the only evidence Shay ever had for the supposed drug lab in Villanueva’s home – came from Rami Najjar, a low-level television actor in Los Angeles that Carreon said was also a confidential informant for the DEA.

“We are quite satisfied that Najjar is a planted tipper,” he said. “All of his conduct indicates it.”

Najjar, who also goes by Rami Joseph, is in his 30s, with Hollywood looks and some minor credits on shows like Pretty Little Liars and Succession. In December 2019, Najjar made plans to attend an ayahuasca ceremony with Villanueva, telling him that he was “looking for a deeper understanding” and an opportunity to “remove blocks from the massive talents I know I have,” according to emails reviewed by New Times.

Their correspondence was initially cordial. Villanueva told Najjar he was an excellent fit for the church. Then, out of the blue, Najjar said he had to cancel and demanded a refund of the $180 deposit he had paid. Villanueva initially resisted, asking, firmly, if Najjar would like to reschedule. (“When you sign up for a ceremony, you committed to the thing,” Villanueva explained. “There are big, giant letters that say, this is not a refund deal.”)

Najjar grew angry: “Reporting your illegal practices to authorities,” he wrote, calling Villanueva a “money hungry fake …Typical old Arizona male,” he added. “Not surprised.”

Villanueva wrote back, offering a refund. But it was too late. The DEA got a call later that day, saying that Villanueva was making DMT himself and then selling the drug.

The suddenly indignant demeanor, the vague claims about DMT manufacturing – Carreon said it struck him as odd. And ever since, Najjar has been elusive. When Carreon attempted to subpoena Najjar, his private investigator arrived just as the actor was moving to a new address, driving a Mercedes without license plates, according to footage New Times reviewed.

After multiple calls and inquiries to his social media accounts, Najjar wrote to New Times that he was “not interested in any story, sorry.” When New Times explained that he had been named in a lawsuit that claimed he had been acting as a confidential informant for the DEA, Najjar did not reply and subsequently blocked the account on Instagram.

The DEA has not outright denied that the tip was planted. In a June motion, federal attorneys argued that, in fact, it did not actually matter whether or not Najjar was a planted tipper. The tip was passed along to Shay at Maricopa County; he investigated, independently, and obtained the warrant.

Carreon’s theory, of course, helps Villanueva’s case immensely – and not just Villanueva’s defense, but Carreon’s lawsuit against the DEA. If Najjar were a planted tipper, that would mean the DEA initiated the investigation into Villanueva, a man who, at that time, had begun threatening legal action against the agency. It would be proof that the DEA was acting in a retaliatory manner. But though Carreon is staunchly confident that it’s all true – he noted that the DEA is notorious for its poorly run informant program – he hasn’t yet been able to produce any supporting evidence.

For now, it’s all a waiting game. Carreon’s DEA lawsuit is crawling through federal court. Unless the federal agencies succeed in their last motion to dismiss the case, it appears likely that it will head to trial, though that could be months or years away. Villanueva, armed with a new defense attorney, plans to put up a fight against his own charges.

Whether or not Villanueva’s prosecution was retaliation, whether or not the pastor is eventually cleared or charged as a drug lord – Villanueva is insistent that he is at peace with it all, perhaps knowing that he could succumb to the cancer before he’s ever served a prison sentence.

Stanley, the pastor with the Tucson church, recalls speaking with Villanueva in jail as his health was rapidly fading. “‘If I’m here for a few months, Scott, I’ll expire,'” he recalled him saying. “‘But, you know, I’m not that attached to this dimension.'”

“I’m trying to give to my fellow person,” Villanueva told New Times. “And this whole legal thing – if it consumes me, and I cease to exist, then that’s the way it goes.” It is only then, when he speaks of what is approaching, that Villanueva’s tone changes, becomes the voice of a minister, a religious man.