Courtesy of the subjects

Audio By Carbonatix

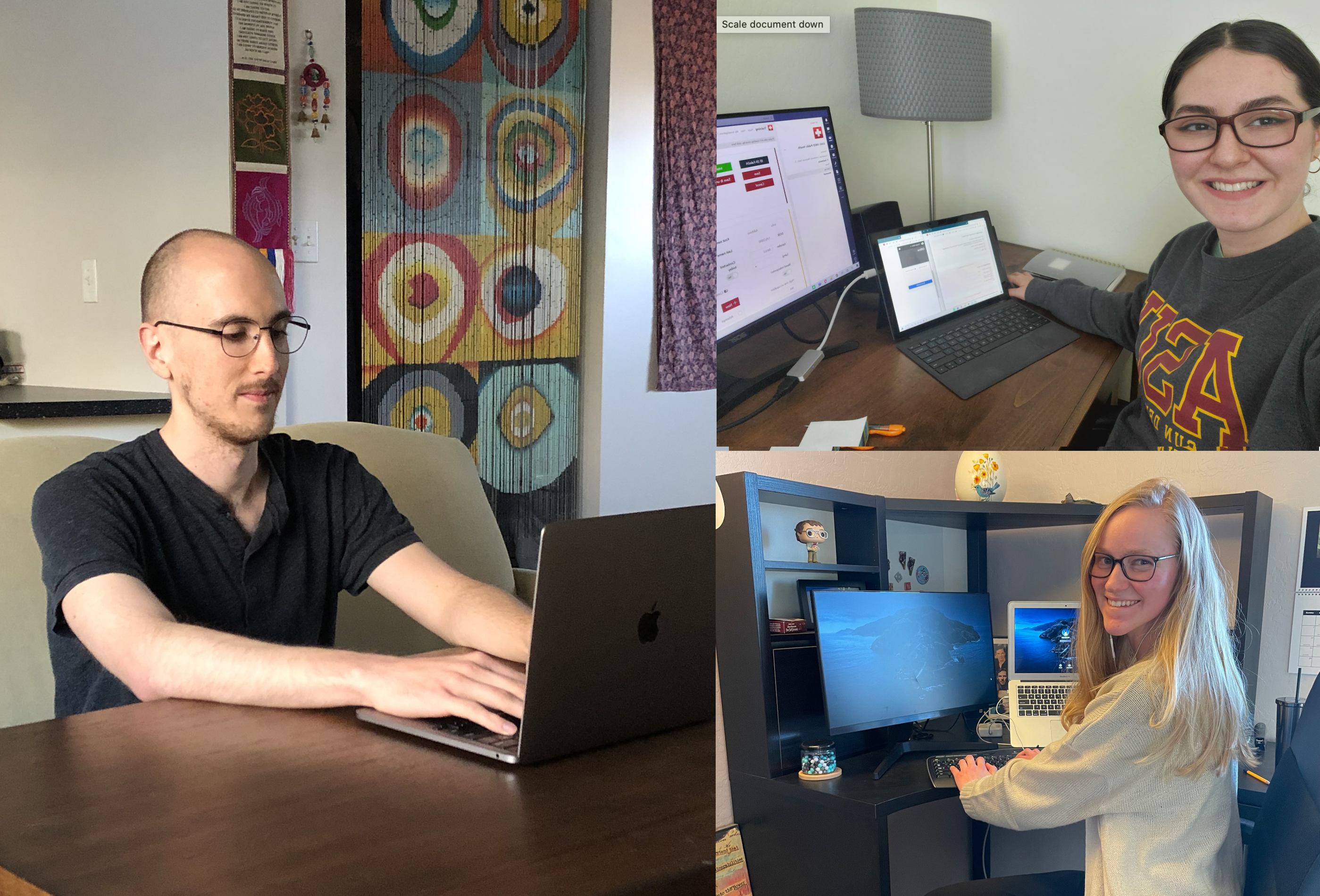

Issa Jimenez Espinoza and Catie Carson sit in their bedrooms, headphones on and a computer in front of them. Ben Van Maren sits on a couch in his studio apartment with a laptop.

They’re talking to people who are at a low point in their lives after either testing positive for COVID-19 or coming in contact with someone who has.

As part of a team of contact tracers operating out of Arizona State University, each call the three make drops them into a different front of the pandemic in Maricopa County: A mom with six kids trying to keep everyone safe after they all contracted COVID-19. A community member who believes they infected a relative with the virus. An employee trying to manage an outbreak in a shelter for refugees.

Team is actually too weak of a word for the contract tracers – strike force might be more accurate. ASU professor and disease epidemiologist Megan Jehn studied for more than 15 years what would happen if a pandemic hit, and now that it has, she’s built an operation dedicated to ending it.

Contact tracing has been used to control infectious diseases for 100 years, but the basics remain the same: talk to infected people, find out where they might have been infected and who they may have gone on to infect, and have those “contacts” isolate to avoid further infecting others.

Even as COVID-19 ran rampant this winter, making it impossible to stay within the 48-hour window the team aims to reach people in, the team persevered, using a strategy that’s more effective at containing smaller, well-defined outbreaks to try to dull the harm of state officials’ lack of action. Besides the sheer numbers that contact tracers have faced, people they call can be hostile, inspired by political rhetoric, or consumed by fear. It’s not the easiest of jobs, but the contact tracers know that they might be the lifeline someone needs, and that each person they’re able to reach in time is a series of infections averted.

“Not everybody is a born contact tracer,” Jehn said. “It is a very special skill set. It requires compassion and empathy – good communication skills. You have to have enough public health knowledge that you can understand the disease course.”

Associate Professor Megan Jehn is heading up a division of contact tracers.

ASU

More than 250 students, faculty, and community volunteers have been recruited and trained to do the work. They run seven days a week, 12 hours a day, with 30 to 50 people a day working in four-hour shifts. On an average day, the team handles around 400 cases for the county. As of last month, they’d closed 31,327 cases, reaching around half of them for an interview.

The team at ASU comes from all backgrounds. Van Maren coordinates care for people with HIV/AIDS at Valleywise Health. Jimenez Espinoza is an ASU senior majoring in biology. Carson is a social-work grad student at ASU.

Jimenez Espinoza and Carson are veterans at this point. They’ve been working the phones for months from their parents’ houses and are now paid for their work. Van Maren is a more recent addition to the team. He said he found a lot of parallels between this work and his work in the HIV field.

“It’s challenging because you are talking to people in the hardest moments and they don’t hold back – they shouldn’t – because they trust you and they trust us,” Van Maren said. “But at the same time, as challenging as it is, it also feels effortless. Because what I’m doing is just giving my time to someone at their worst moments.”

Jehn started planning to build the contact-tracing team early last year, when the pandemic hit. The university has long had a service-learning internship tracking outbreaks of infections like salmonella, so she began scaling it up. By early April last year, she had received 500 responses from people willing to volunteer. When the county asked for the team’s help last summer, she was ready to go.

The effort includes tracers who speak eight to 10 different languages; a separate team of Spanish speakers has more than 15 members.

“I think that my relationship with [the work] has changed a bit over time,” Carson said. “Back in July, I was impacted by the choices I was making, but nobody that I knew had been affected by it yet. And I think as we’ve gone through the year, it’s become harder and harder. It just feels like it’s gotten closer and closer. And there have been more people who’ve been personally affected in my own family or friends and so it does begin to feel a bit more personal.”

Laura Meyer, one of the program managers who run the tracing teams, is a social worker and was recruited to train investigators in empathetic communication skills used in the medical field. Speaking with the three contact tracers, her impact can be seen. They engage in reassuring, measured tones with solid eye contact. They seem calm and knowledgeable, happy to listen.

Some of the members of the team who do contact tracing out of ASU.

Courtesy of Megan Jehn

The teams work remotely, in shifts of up to 15 people connected through a running Zoom meeting. What they often find – despite the governor’s pronouncements about “personal responsibility” – are systemic issues that make it hard for infected or exposed people to follow public health guidance.

“Some of the common themes that we would see is people needing to get back to work, or needing to quarantine and having issues with their employers,” Carson said. “[Or] being told they have to come back when they’re still caring for people at home.”

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to the team’s efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 has been a lack of matching mitigation efforts to stop people from being infected in the first place. Jehn is intimately familiar with this issue. She’s part of an ASU modeling group that predicted the winter holiday spike in cases in advance. The modeling group’s calls for enhanced mitigation measures to curb the spread and save lives – calls joined by state hospital leaders – fell on deaf ears.

“I don’t think anyone could have [initially] predicted Arizona being a global hotspot twice,” Jehn said. “And the level, the surge of the cases that we were seeing just in terms of absolute numbers: 10,000, 11,000, 12,000 cases a day that have to be investigated, contact-traced. It’s really insurmountable at that point.”

Effective contact tracing tries to reach people within 24 to 48 hours after testing positive. This winter, the volume overloaded the pipeline and the ASU team was receiving cases from the county a week late. A county spokesperson attributed the delays to overloaded laboratories.

Despite the overwhelming scale of the enemy they faced, Jehn and the contact tracers still believe their work makes a difference. Even if they can’t get to everyone, each person they’re able to reach is one chain of infection they’re able to break.

“We still are able to learn about the contacts this case has had, we still can follow up with them. We can still figure out more about what’s going on in the community and how COVID is spreading and how we can stop the spread and better cut off chains of transmission,” Meyer said.

Last year, Jehn led a team that conducted a survey of how widespread COVID-19 had been in the community.

Andy DeLisle // ASU

As they do that work, the tracers at ASU are also offering a sympathetic ear and the possibility of a referral for material support: a hotel to isolate in or food deliveries to those isolating at home. Sometimes what a person needs most is someone to talk to; Jimenez Espinoza said it’s not uncommon for her to be on a call with an elderly person for 30 to 40 minutes.

“I’ve been volunteering for other institutions, like hospice and free clinics, but I’ve never had so much of a one-on-one conversation or such a close relationship with these patients or cases,” she said.

Other challenges come from upset people who don’t want to talk with tracers or be honest about the activities that may have put them at risk. Jehn said that during the election cycle they encountered more people angry at public health officials and wondering how the tracers got their contact information.

“You never know if you’re going to get a mom who’s upset because her kid can’t play soccer, right. And so sometimes, you have one of those calls and you’re just like ‘Wow, you have completely lost perspective here,'” she said. “And then, on the absolute opposite end, a woman who had recently lost her spouse, and she was serving as the proxy interviewee. He had just passed away in the ICU. Being on a call with somebody like that, that stays with you.”

COVID-19 has receded in the state in the last two months and vaccinations offer hope on the horizon, but the ASU team continues its work.

“I think this is a way that I found to perfectly [meet] the needs of the people who are currently going through COVID and testing positive, while also staying safe, and then allowing my family to be safe,” Jimenez Espinoza said. “I do it from my room.”

At the end of each day, the detailed data is logged into a system to share with the county and state. Cases in high-risk settings are flagged for follow-up. While some jurisdictions have released detailed information on their contact-tracing findings, Maricopa County has not.

One issue, Jehn says, is the sheer volume of the data collected from the detailed questionnaires that the tracers go through. Finding patterns would require standardizing responses and analyzing a huge amount of collected information. While it might not be able to help us now, that data will help epidemiologists study how COVID-19 has spread and plan for the next pandemic.

“Early on, I don’t think anybody in public health epidemiology was ever thinking that we would get to numbers quite that high,” Jehn said. “So, I’m happy seeing all of these wonderful students being exposed to public health and getting this opportunity to give back to the community … but at the same time, living through this as a public health professional is, is frustrating, and discouraging, and -” she trails off and falls quiet. “Got enough?” she asks after a long silence. She’s ready to get back to work.

If you get a call or text from “Public Health,” you can google the number to verify it. Please respond, Jehn asks. It’s anonymous and can help protect the community.