John Moore/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

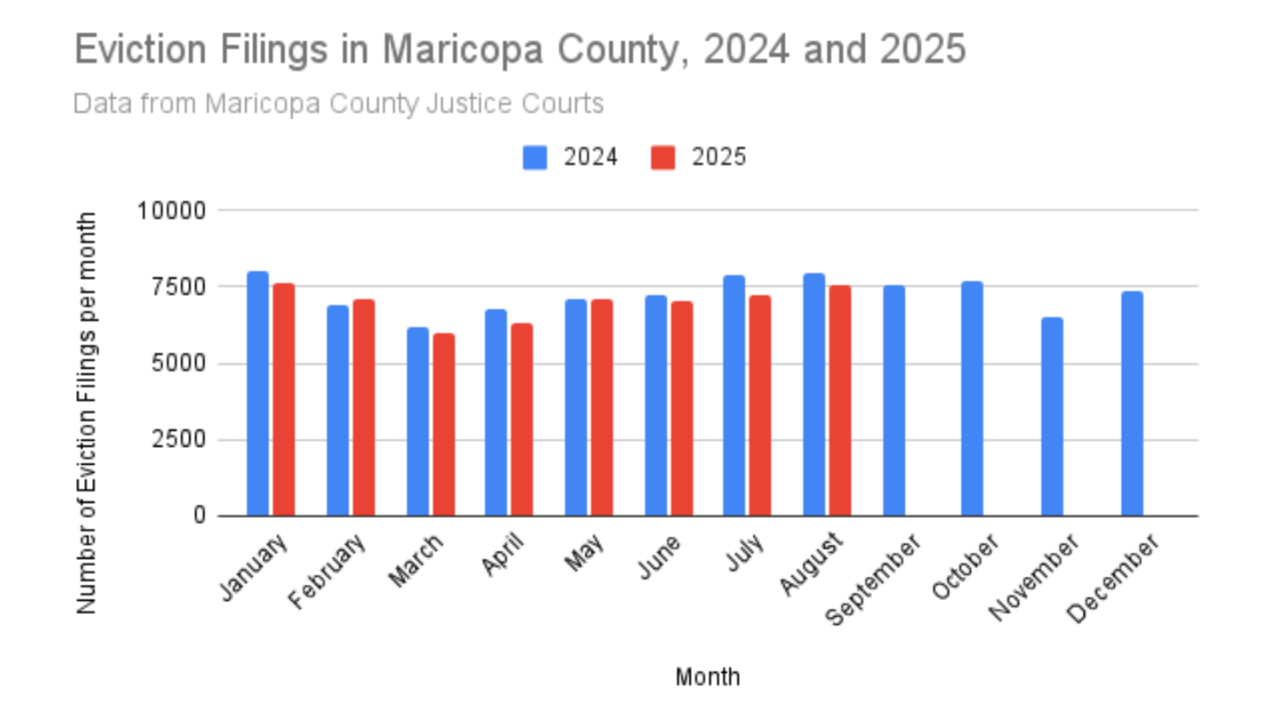

Last year, Maricopa County set a record with 87,000 eviction filings. It doesn’t appear the county will break that record this year, but it’s still on pace for the second-most eviction filings ever recorded.

Last year, 87,197 evictions were filed in Maricopa County courts, according to the Maricopa County Justice Courts data. That broke a 2005 record of 84,000 eviction filings. So far this year, the number of eviction filings has tracked relatively close to last year’s rate. Nearly 56,000 evictions have been filed through the end of August and two months – February and May – saw slightly more eviction filings than the same months in 2024, according to Justice Courts data.

If filings remain consistent for the rest of the year, Maricopa County should end up with more than 84,000 filings, just beating out the 2005 total for second-most ever, Justice Courts spokesperson Scott Davis wrote in a press release.

Though an eviction filing doesn’t always translate to someone being kicked out of their home, it’s considered a solid measure of overall evictions. Since many people are also displaced through informal eviction, which doesn’t show up in eviction filings, many housing policy organizations consider filings to be an accurate estimate of total evictions.

The Valley remains in a housing crisis, and that eviction filings are again tracking toward historic territory is “one of the least surprising things I could imagine,” said Drew Schaffer, the director of the William E. Morris Institute for Justice, a non-profit focused on protecting the rights of low-income Arizonans. Other than an increase in housing stock, which hasn’t trickled down to low-income households most impacted by eviction, “nothing has changed” that would decrease eviction filings, he said.

“If anything, it’s probably getting more challenging out there for families,” Schaffer said, noting that housing and rent costs have continued to increase, already-strained safety net programs have been slashed and goods and services cost more. Additionally, services to help families pay their rent, such as rental assistance and legal support, are essentially nonexistent or severely underfunded in Arizona.

“We’re in the midst of a code red emergency,” Schaffer said. “We are the eviction capital, or one of the eviction capitals, of the United States.”

Morgan Fischer

Arizona has taken some measures to combat Phoenix’s housing crisis. More than 53,000 housing units have been built or preserved across the city since June 2020. Still, eviction filings and housing prices have remained high because building alone “doesn’t undo the foundational problems with the housing system,” said Sebastian Del Portillo, a spokesperson for Organized Power in Numbers. “It’s a piece of the puzzle, but it’s not the solution.”

Another piece of the puzzle, often missing in Arizona, is civil legal aid. Attorneys and legal support can often help tenants avoid eviction, but less than 1% of tenants have legal representation when facing eviction. Civil legal aid organizations can provide that service, but they have limited funding and can help only a limited number of people.

Until recently, Arizona was one of three states that provided no state money to civil legal aid organizations, of which it has three. This year, however, lawmakers passed a state budget that allocated $3 million toward civil legal aid. Previously, organizations like Maricopa County-based Community Legal Services had to rely almost entirely on federal funding to operate. With Donald Trump in the White House, that federal funding, which amounts to $16.5 million for Arizona groups, may be in danger.

Right now, there’s a lot of “uncertainty,” Schaffer said. Congress is facing a potential partial government shutdown in 14 days, but it’s expected to pass a continuing resolution, which temporarily extends federal funding at its current levels.

Outside of state and federal funding, advocates have been pushing for the city of Phoenix to fund a “right to counsel” program to guarantee legal representation for tenants, which could lower eviction rates. Many members of the Phoenix City Council signaled their support of the program, and this year, the council dedicated $1.2 million in pandemic relief funds to start a pilot program. But it could still be years before the council takes any action to create a permanent right-to-counsel program.

“Until those policy matters are addressed with sufficient investment,” Schaffer said, “We’re going to continue to see the high levels of eviction filings.”