Hannah Critchfield

Audio By Carbonatix

If Breanna Gonzales is tried and imprisoned as an adult, prosecutors will trace the conviction back to a moment earlier this year, when the 17-year-old attacked a juvenile correctional officer.

Her grandmother, Corene Smith, said Gonzales’ troubles began much earlier. She just isn’t sure which moment she’d pick.

Maybe it begins with a 2016 evening in Flagstaff, when a 14-year-old Gonzales called police for help after she’d been raped, only to be thrown in jail for running away.

Maybe it started earlier that same year, when she was raped by yet another man in his 30s as she attempted to flee her hometown of Cottonwood. Or maybe seven months later, when she was kidnapped by a third man in Scottsdale, who also assaulted her.

Or perhaps it begins when Gonzales was just 13, the first time she was arrested for being out of the house.

“This all started with running away,” Smith said. “All she was doing was running away.”

By the time she attacked the officer, Gonzales was already one of the estimated 2,300 young people, the majority of them girls of color, in jail for status offenses – acts that would be legal if committed by an adult. Gonzales, who turns 18 today, has spent the last four years in and out of various juvenile detention facilities. Almost all of her previous arrests stem from running away, at least two of them occurring after she’d been raped and officers were called for help.

For this article, Phoenix New Times reviewed police reports, victim notification letters, and records from the Department of Child Safety, the Department of Juvenile Corrections, the Department of Economic Security, the Coconino and Yavapai County Attorney’s Office, the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office, Superior Courts in Yavapai, Coconino, and Maricopa counties, and Adobe Mountain School. The documents, obtained using public records requests or provided by her mother, Julieann Gonzales, weave a picture of Breanna Gonzales’ turbulent life prior to the point of the attack.

Her family said she never received the treatment she needs for her complex trauma – and worries that if she’s now tried as an adult for her violence against an officer, she may never get the chance.

Advocates for juvenile justice argue that punitive measures will do little to address the root causes of Gonzales’ violence, and will push her further into a system ill-equipped to deal with her developmental needs – at the expense of the minor’s health and future public safety.

As prosecutors emphasize the need for current public safety, a look back attempts to explore what her grandmother has wondered for years – what brought Gonzales, and her alleged victim, to this point?

Inciting Incident: The Attack

Earlier this year, Gonzales allegedly violently attacked an Adobe Mountain School juvenile correctional officer who had been taking Gonzales back to her cell, punching the woman repeatedly in the head.

On April 12, 2019, the pair was returning from the juvenile detention facility’s Girls Temporary Stabilization Unit, a short-term crisis intervention unit for mental health emergencies. According to prosecutor testimony, Gonzales turned to the officer beside her and began to hit her.

Gonzales allegedly punched the officer, Sandra Montoya, about 30 times in the head. Montoya was taken to the hospital, then transferred to an in-patient rehabilitation facility for four weeks of treatment after being diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury. The long-term extent of the damage is still unclear. The correctional officer, who currently works light duty in the facility’s warehouse, declined to comment on the incident or her health, citing the ongoing case.

Gonzales was transferred to Lower Buckeye Jail, an adult facility, where she is currently being held.

State prosecutors are now attempting to try Gonzales as an adult for the alleged crime. She stands accused of two felony charges: one count of dangerous or deadly assault by a prisoner, and one count of aggravated assault.

Luis Valenzuela, criminal investigator with the Arizona Department of Juvenile Corrections, who was not present for the attack but had read officer reports of the incident, said in his grand jury testimony that the alleged assault was “totally unprovoked and without warning,” calling it a “hit-and-run kind of a situation.”

Valenzuela told the grand jury he didn’t know the protocol involved in bringing a juvenile inmate back to their cell at Adobe Mountain.

Montoya declined to speak with New Times. And ADJC officials have yet to release video footage of the incident. Information remains sparse on what protections were in place for both Montoya and Gonzales should something go awry.

Gonzales has not had a chance to provide her own testimony. But her family says the state witnesses’ characterization ignores a long, well-documented history of trauma, including several severely damaging interactions with law enforcement.

Breanna’s Past

Breanna Gonzales, a member of the Cherokee nation and a Mexican-American, was born in Cottonwood in 2001.

She grew up in a home where her father regularly beat her mother in front of her and her three siblings, according to CPS records and her grandmother, Corene Smith. The children were transferred into the custody of their grandmother in 2013, a few months after Gonzales turned 12. Smith, along with caseworkers during this time, stress the severe impact the family violence and separation had on the children, particularly Gonzales, who CPS reports note the other siblings blamed for the separation (reasons for this are unclear).

Gonzales began running away from home shortly thereafter. By early 2015, when Gonzales was still 13, her arrest record began to appear, with the Yavapai Sheriff’s Office booking her into jail on charges like “runaway – incorrigible child” and “probation violation” (a common charge if someone has previously been in trouble for running away).

One day in April 2016, she again fled the house. Now 14, she had recently started at Big Park Middle School after being bullied at her previous school, and her grandmother said she was struggling. While on the run, she was picked up by a man in his 30s who promised to take her to Mexico. He raped her instead. He was later arrested and convicted of sexual conduct with a minor. Gonzales never returned to middle school.

Police continued to arrest Gonzales for violating probation after running away throughout the summer, once for shoplifting, and for two separate cases of possession of marijuana. (Gonzales was diagnosed with substance abuse disorder for methamphetamine and marijuana addiction by at least early 2016). She was held in Yavapai County Juvenile Detention for several days in late August. Then, she was released and ordered to abide by house arrest. That same day, she was supposed to attend her first day as a freshman at Mingus Union High School.

Gonzales fled instead. She was missing for 17 days, until her grandmother received a frantic call. Gonzales, sobbing, said she’d been raped by a man in his 30s, and was at a Super 8 motel in Flagstaff. Panicked, Smith called the police for help.

Coconino County sentencing reports say the man had offered Gonzales, who was intoxicated, a ride. He drove her to his apartment, and began to undress her in his car. Gonzales tried to fight him off, and asked him why he was doing this, to which he replied, “Because I can.” He forced her to have sex with him in the front seat. Afterward, he told her he was “not going to go to jail over her,” drove to the Super 8, and threw Gonzales out of the car. (The man was later arrested and confessed to having sex with Gonzales, though he claimed it was consensual. He convicted of sexual abuse.)

Flagstaff police arrived at the hotel. But because Gonzales had violated her probation by running away, there was a warrant out for her arrest. So after being taken to Flagstaff Medical Center for evaluation, the rape survivor was thrown in local juvenile jail, where she remained for 11 days, celebrating her 15th birthday in detention.

Status Offenses

The number of children in jail nationally has been declining in recent years – but not for incarcerated girls, who now account for more than 30 percent of the juvenile justice population. Both the criminal justice and juvenile justice systems were designed with boys in mind – research suggests this means justice professionals often critically fail to catch and address signs of trauma, particularly when it’s related to sexual violence, which girls disproportionately experience.

Statistics show that judges are more likely to incarcerate girls for “status offenses” – acts that are only illegal because of a youth’s status as a minor, like breaking curfew, skipping school, or running away. And these offenses are often rooted in the experience of abuse and trauma. One in every five runaway cases overall is linked to past abuse, according to the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit research and policy organization dedicated to national justice system reform. Native American and Latina girls are disproportionately at risk to be sent into the justice system for these crimes.

The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, passed by Congress in 1974, recommends that status offenders not be held in secure juvenile facilities, either for detention or placement. But a few years after its passage, a “valid court order” exception was added to the bill. Now, in Arizona and other states, if the status offender violates a valid court order, like a judge’s verbal command to “stop running away” or a probation order that requires the minor to attend school and observe a curfew, the child can be incarcerated. In Arizona, youth as young as 8 can be classified as “incorrigible children” in status offense cases.

Because of Yavapai County Court policies that protect the minors’ privacy, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when Breanna Gonzales first entered the juvenile justice system, or if it was the crime of running away that first put her on probation, as her family suggests. What’s clear is that once she was on probation, fleeing from home was the offense that kept bringing her back to jail, even after becoming a victim of sexual assaults.

Breanna Gonzales, around age 13, the year she started getting in trouble for running away.

Julieann Gonzales

Into Adobe Mountain

Her grandmother said things snowballed after her second rape: The girl got into a fight a few days after her release from jail, incurring misdemeanor charges, and was found to have vandalized a property during her first few days as a runaway in September. A Yavapai County judge reviewed these charges, as well as her probation violation for running away, and decided she should receive treatment for a year at Mingus Mountain Academy, a residential center for emotionally and behaviorally at-risk adolescent girls.

While there, life was difficult for Gonzales, according to her grandmother, her mother, and CPS progress reports. She was frequently physically restrained due to self-harming behavior, scratching her arms and face until they bled, and attempting to run away. She often begged to be sent home, and her mother and grandmother eventually convinced the court to move her to The New Foundation, a treatment center near Phoenix, where her mother was living at the time. Here, she succeeded in running away again in April 2017.

A third man in his late 40s picked up the teenager. She was found by police at a McDonald’s on 51st Avenue and Indian School Road three days later. The man, Rhone Eugene Beals, was apprehended at a nearby storage unit, where he had repeatedly raped Gonzales, according to her mother. He was found guilty on charges of kidnapping, according to Maricopa County records, though his charges of sexual assault, child sex trafficking, and transfer of drugs to a minor were dropped on plea deal. He and the other two men convicted of harming Gonzales, Gregory Mitchell Clark and Derek Hadley Paddock, are still serving sentences in Arizona prisons between five and 13 years.

And Gonzales? After being assessed for the rape, she was again taken to jail for violating her probation.

This time, she didn’t return to residential treatment. The court committed her to the Arizona Department of Juvenile Corrections, who sent her to Adobe Mountain School, the department’s secure facility for juveniles, which is intended to provide rehabilitative services to youth in its care.

Inside Adobe Mountain, therapy programs are delivered by trained staff five days a week, according to AJDC policy and Kate Howard, AJDC spokesperson. All programs provide cognitive behavioral therapy for a range of issues, Howard said, like negative thinking patterns and anger management. The Temporary Stabilization Unit, which is operated by a licensed mental health clinician and where Gonzales was a frequent visitor, is intended to de-escalate juveniles in crisis who are an imminent risk of injury to themselves or others.

But her mother and grandmother alleged that guards and other staff were ill-equipped to appropriately handle Gonzales’ worsening emotional state.

She frequently harmed herself with her fingernails and available objects, and when officers tried to restrain her, they often injured her in the process. Gonzales once had to receive eight stitches on her chin when a guard forced her to the ground, family members said, and frequently had bruises from where officers pinned her down with their knees. In a video visitation with New Times, Gonzales said officers would often put her in “separation,” a form of solitary confinement, or “the chair,” which restrained her arms and legs. Her family fears this treatment served to re-traumatize her.

Adobe Mountain School, ADJC’s last secure prison for children, has long come under fire for its inability for provide adequate mental health services. Because ADJC is part of the executive branch, there’s little outside review of the facility, and privacy laws that protect children’s records also serve to safeguard against scrutiny. Previous New Times reporting as far back as 2001 revealed a pattern of neglect at the institution, eventually resulting in a DOJ investigation after three children in its care committed suicide.

A January 2016 report from the Children’s Action Alliance and the Morrison Institute for Public Policy at Arizona State University cautioned against using the facility for mental health services, and a 2017 investigation by the New Times found that some children at Adobe simply were never sent to the mental health unit, even after threatening suicide and reporting hearing voices.

Gonzales’ state worsened, ADJC records show. Her release date continued to be pushed back, with Adobe staff often citing her need for treatment for additional self-harming behavior, her mother and grandmother said.

She was finally released for mental health treatment at the Quail Run Behavioral Health center in November 2018, according to her grandmother and ADJC records. She and her grandmother met with CPS shortly after arriving who told them they were considering transferring Gonzales to a treatment facility in a different state.

Gonzales immediately became upset, said Smith, her grandmother. “She fell to her knees and freaked out. It was a huge scene. She ran out of the room screaming and crying,” Smith said. She added that possibly, Gonzales believed if she was sent back to Adobe, she’d keep seeing her grandmother, who had visited there every Sunday.

Gonzales fought with a medical professional shortly after arriving, ADJC records show, possibly during the process of being restrained during this outburst. She was soon readmitted to Adobe.

She remained there until April 2019, when she committed the attack on Montoya and was transferred to the county’s Lower Buckeye Jail.

In total, she’d received five months of consistent residential mental health treatment outside confinement, and spent many more days in police stations, jails, and juvenile detention.

The Abuse-to-Prison Pipeline

Criminal justice officials need to create better ways to cope with juveniles like Gonzales who have had a history of trauma, according to Rebecca Epstein, executive director of the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality.

As the co-author of a groundbreaking 2015 report on sexual trauma and juvenile justice, Epstein’s one of the country’s leading experts on the issue.

“In many ways, this case is an example of the system responding to a girl of color who has experienced trauma by punishing her,” Epstein said. “When we punish these children the same ways we punish adults, it is not accomplishing the goal of increasing public safety. Instead, it’s depriving these girls of the very kinds of supports and services that they need in order to heal, and to thrive, and to be less likely to engage in the type of behavior that’s being punished.”

The 2015 report, entitled “The Girls’ Story: Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline,” found prior sexual abuse to be a primary predictor of juvenile justice involvement. The multistate study found that 39 percent of girls within the justice system have been raped, and over half had experienced domestic abuse.

Experts already knew that childhood trauma is associated with involvement in the system. But the new study found that for girls, the link appears to continue even when they’re released. It found that sexual abuse is one of the strongest predictors of whether a girl will be charged again, and that such abuse has a greater impact on girls’ re-entry into the juvenile justice system than other risk factors like behavioral problems.

“We treat the body like it’s separated from emotions, thinking, and behavior,” said Robert Rhoton, CEO of the Arizona Trauma Institute, which provides training in trauma-sensitive care. “We can’t tolerate people punching each other, but the reality is, a lot of times, what we find is that that a kid’s behavior was exactly correct biologically.”

After trauma, he continued, some people may spend every day in what he called “Hulk mode.”

“Their system is so jacked up, and the real problem is the adults aren’t trained to recognize it or calm their bodies down,” Rhoton said. “What they try to do instead is exercise control over them … We’ve designed institutions that keep saying the way to deal with a kid who’s having a Hulk moment is to punish, shame, and try to control them.”

New Times attempted to contact several agencies and organizations for greater context on juvenile justice in the state and how to balance issues of trauma with the need for public safety. The Arizona Juvenile Justice Commission, Arizona Criminal Justice Commission, and Governor’s Office of Youth, Faith and Family, which receives federal funding to provide assistance on juvenile justice issues within the state, all declined to comment on the case in time.

Jail Life

Lower Buckeye Jail is currently the only facility in Maricopa County with a mental health unit, through a contract with Correctional Health Services, though critics have long questioned the facility’s ability to adequately care for vulnerable detainees that come to the unit for treatment. Gonzales’ family also found the byzantine system and rules of the jail system incredibly frustrating.

For the first four months of her incarceration at Lower Buckeye, her family’s questions were met with silence, and Breanna Gonzales was not permitted to see or speak with anyone outside the facility. Julieann Gonzales said she finally requested to talk to a lieutenant to complain; her daughter was able to have visits the next day.

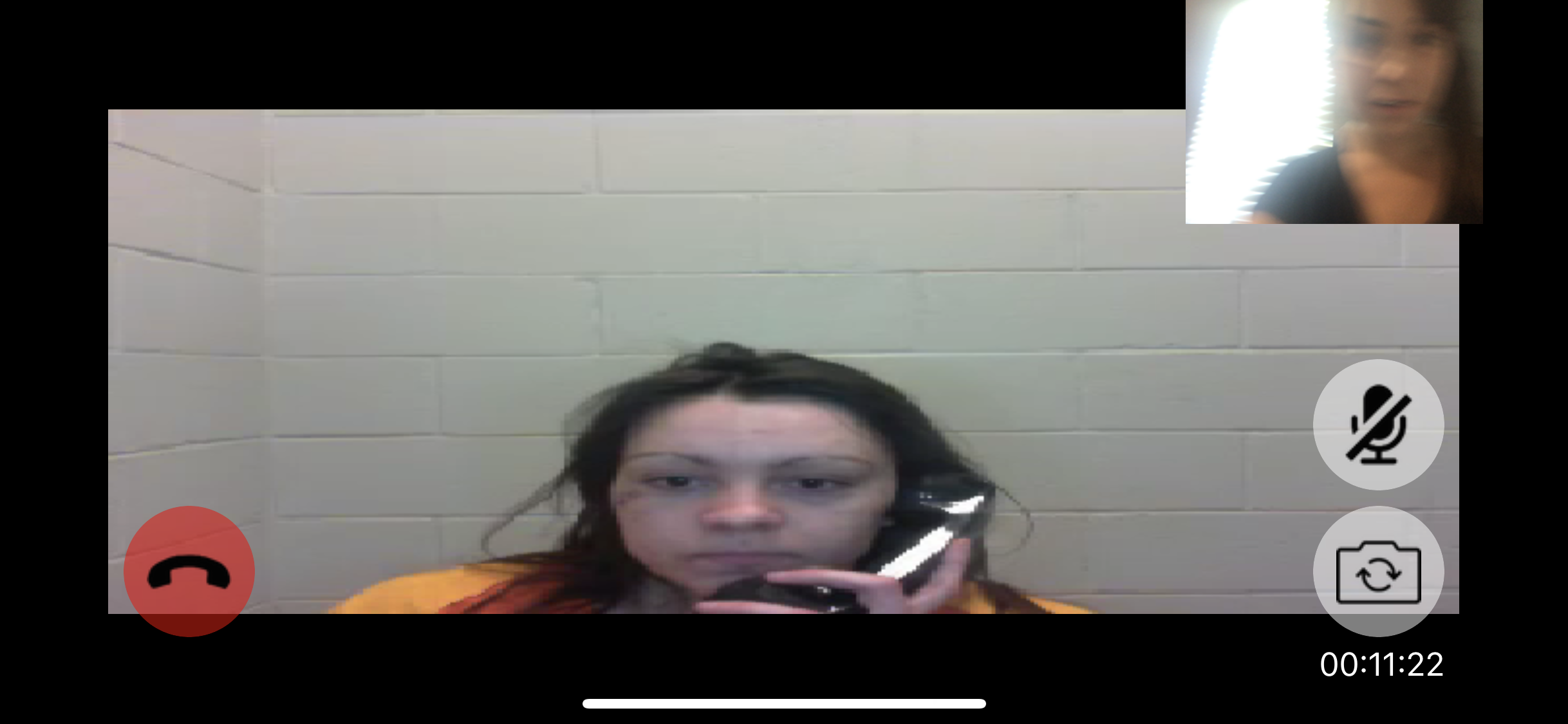

In a video visitation with New Times in mid-September, Gonzales’s face and arms were marked with self-inflicted cuts and scratches.

Breanna Gonzales, then 17, speaking to New Times in Lower Buckeye Jail.

Hannah Critchfield

Gonzales said she’s on Zyprexa, a medication that treats bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, as well as another medication she didn’t know the name or purpose of.

“They’re okay here, but like officers at Adobe, they just don’t know how to deal with the self-harm,” she said.

Because of her self-harm, she said, she was at one point restrained for 48 hours straight, her hands and legs handcuffed and spread out on a bed.

When she spoke to New Times, she had only recently been allowed to leave her cell for an hour each day. During her first four months, she was kept in 24-hour confinement, she said, and had to earn her right to wear prison clothes, rather than just underwear, (a standard practice for inmates booked into the mental health unit).

Gonzales didn’t seem to fully understand what she’s accused of doing. When she spoke to New Times, she said she remembered feeling angry that day, and got into a fight with Officer Montoya. But she appeared shocked when reminded that Montoya had been hurt badly.

On September 18, Gonzales was placed in an adult courtroom for a hearing. She wore a standard orange jumpsuit, but the sleeves of her shirt were yellow, indicating she was a minor.

At the proceeding, Tammy Velting, Gonzales’ mitigation specialist, advised the family to stop speaking out about Correctional Health Services, Gonzales’ mother said. Velting reminded the family that the health care provider has written documentation of Gonzales spitting or kicking during restraint while receiving mental health treatment in jail, and that the documents could be used as retaliation against her in the form of future charges.

Velting declined comment to New Times.

Advocacy

Julieann Gonzales, Breanna’s mother.

Hannah Critchfield

After Gonzales’ most recent court date, her mother reached out to Puente Human Rights Movement, a local grassroots organization. Together with Valentina Gloria’s mother, Vangelina, they held a press conference outside the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office on September 9, the day of County Attorney Bill Montgomery’s resignation before being sworn in as a state Supreme Court justice, calling for the two girls’ release.

“Bill Montgomery got to resign today, and he did not stop for a second to look at the people he’s hurt,” María Castro of Puente said.

“We need to stop criminalizing normal responses to trauma,” said Tasha Menaker, chief strategy officer at the Arizona Coalition to End Sexual and Domestic Violence, who also spoke at the press conference. “This will be best addressed outside the criminal justice system. We need to do better for these young women.”

What Gonzales’ family wants is for the girl to be placed in another in-patient facility for therapy that can address her complex needs, with staff that are trained in de-escalation.

The prosecutor’s office, when asked about Gonzales’ charges and claims of her need for treatment, offered a brief statement:

“MCAO is well aware of the challenges that come with balancing the needs of an offender with the needs to protect the public,” said Amanda Steele, spokesperson for the county attorney’s office. “MCAO remains committed to resolutions that accomplish both of these goals.”

Unresolved Issues

After four years in the juvenile system, Breanna Gonzales said she just wants to go home.

Her grandmother said she’s just plain tired.

“She needs to get out of that jail … she’s going to get worse,” Smith said. “She’s only ever gotten worse. How’s this going to help her?”

Gonzales is supposed to be released on bail on Thursday night, before the end of her 18th birthday. But she may be back behind bars before too long. If she’s convicted for the attack on Montoya and gets the maximum punishment, she could be sentenced to more years for her crime than all three of her rapists combined.

And if she’s given probation or a relatively short prison term, whether she’ll get the intensive care she needs depends on the judge overseeing her case – and if the judge has experience working with juveniles.

Stephen Rubin, a retired Arizona Superior Court Judge in the Juvenile Division and past president of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, said he tried to see kids coming in front of him at the adult criminal bench as kids, not adults. He emphasized that his comments were only based on what he’d heard of the case.

“I would ask for everything – psychological evaluations, school records, all their history – before deciding what the sentence was going to be,” Rubin said. “There’s so many red flags in [Gonzales’] case. The runaways and the sexual assault, with the additional trauma of a traumatic childhood, are really strong potential indications of sex trafficking. No child should be sent to Adobe Mountain for a misdemeanor, no matter how many times they violate probation. Ever. This child obviously needs intensive counseling, possibly residential treatment. But she had no business being in the Department of Juvenile Corrections to begin with.”

He added that if he were a judge in her case, he’d seek evidence to “justify the lowest possible sentence.”

Having raised her $20,000 bail fee, Gonzales’ family still has hope for her future. They’d like to place her in a trauma-intensive residential center in Phoenix during her temporary release, where she can receive mental health treatment while she awaits trial.

Breanna Gonzales, prior to her incarceration at Adobe Mountain School.

Julieann Gonzales

Asked about whether she was at all concerned about her granddaughter attacking another person, Smith replied:

“Honestly, I don’t feel she would do that,” Smith said. She believes, based on conversations with Gonzales, that the girl lashed out at the officer in the misguided belief that staying in the state and near her family with more criminal charges would be better than being transferred out of state.

“I know it’s hard for people to believe, but they don’t understand the way this child thinks,” Smith said. “She’s messed up, and she’s been gone for so long.”

And if she’s wrong?

“Then she’s going to go away for a long time. I don’t want that either,” her grandmother said. “But she hasn’t even had the chance to know what life is, really. As people in the community we have to give her a chance, you know?”

If Gonzales is ever fully released from the justice system, the family plans to leave Arizona, and return to the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, where her grandmother believes there will be better services for Breanna.

“We’re all going back home, and I just don’t want to leave Breanna,” Smith said. “There’s just no good memories for her out here.”

Breanna Gonzales’ next hearing is scheduled for November 7. Public Defender Alexandra Evans, Gonzales’s attorney, declined to comment on the ongoing case as a matter of policy.