Zac McDonald

Audio By Carbonatix

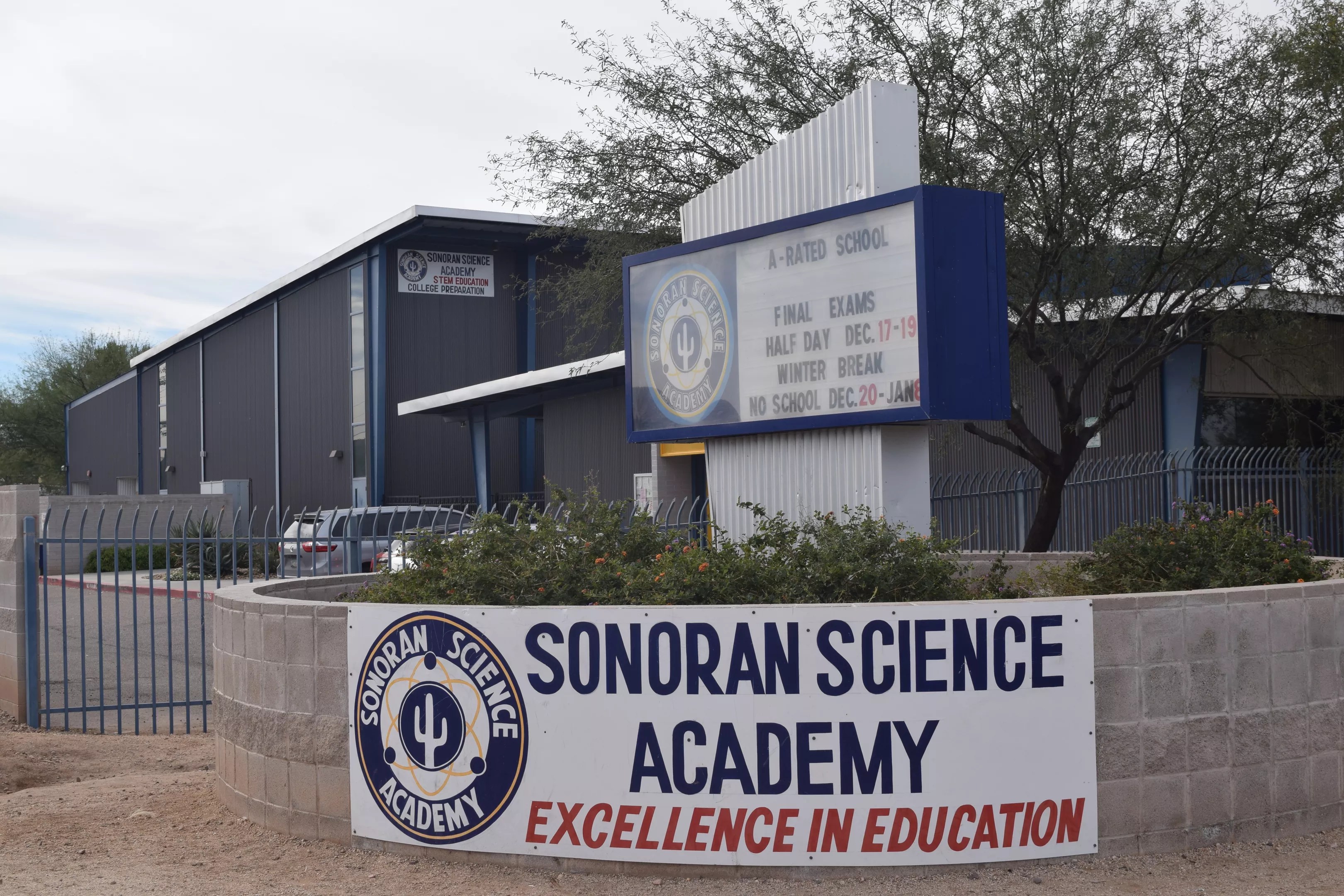

Jessica Avery had been looking to transfer her fourth-grade daughter to a new school when the flyer from Sonoran Science Academy arrived in the mail.

At the time around two years ago, Avery was unhappy with her daughter’s Tucson charter school. She found the administration to be standoffish and unhelpful. The advertisement promoting Sonoran Science Academy, a publicly funded Arizona K-12 charter network with a focus on science and technology, seemed like the perfect fit for her kids. Their family has always tried to give the kids an extra push academically, Avery said.

The warm welcome they received while visiting the Sonoran Science Academy campus on the east side of Tucson, north of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, helped seal the decision. “Touring the school, when they talked about community, and how the teachers interacted with the parents, we were just like, ‘This is it. This is our new home,'” Avery said.

She transferred their daughter immediately, midway through her fourth-grade year. Their son joined the school later, once the school had an opening.

But when they joined the charter school, some things struck Avery as odd: There were lots of Turkish teachers and staff. Also puzzling was the school’s offering of a Turkish-language class. Her daughter wanted to learn Spanish, but the class was full, so she was placed in the Turkish course.

“My daughter thought, okay, this is weird – completely different, you know?” Avery said. “But I think it’s just a great opportunity to learn that.”

The Turkish-ness of Sonoran Science Academy might seem like a peculiar coincidence. Yet when Avery walked into Sonoran Science Academy two years ago, experts say, she had unwittingly stumbled into a conflict in Turkey that can be mystifying to the average American.

Observers and critics link this charter network to the Gulen movement, a secretive Islamic socio-religious network founded in Turkey by the aged cleric Fethullah Gulen, who lives in exile in Pennsylvania. The Turkish government and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan blame Gulen and his followers for the failed coup of July 15, 2016. Gulen denied any involvement in the attempted coup, and condemned the plot to overthrow the democratically elected government of Turkey.

Contradicting experts, the Sonoran Schools charter network in Arizona denies any institutional affiliation with the Gulen movement.

Sonoran Science Academy – Tucson. The first Sonoran Schools charter school opened in Tucson in 2001.

Joseph Flaherty

Sonoran Schools operates six charter school campuses: three in Tucson and three in Phoenix, Peoria, and Chandler. The first charter school opened in 2001 in Tucson as the Daisy Science Academy, and since then, the network has acquired a reputation for a focus on science, technology, engineering, and math, and a diverse student population. Today, 2,560 students in Arizona attend one of the academies. The charter network also operates a Tucson preschool.

Sonoran Schools and its parent nonprofit organization, the Daisy Education Corporation (DEC), declined interview requests for administrators, and responded only to written questions. “DEC has no links to any non-educational entities. DEC is a non-profit corporation founded solely to meet a need for Arizona students,” the charter network said in a statement. “It was established in accordance with all applicable local, state, and federal guidelines, regulations, and laws.”

There are thought to be more than 150 schools affiliated with Gulen in the U.S., and thousands across the globe. The movement is under increased pressure since the turbulent days after the attempted coup in Turkey. The Turkish government has carried out a sweeping purge of academics, journalists, judges, and military officers thought to be members of the Gulen movement – no matter how tenuous the evidence – in a roundup that continues even now.

Secrecy and obfuscation seem to be a survival strategy for schools founded by members of the Gulen movement. “They have always been kind of vague about the organic, institutional link with the Gulen movement,” said Omer Taspinar, a Turkey expert at the Brookings Institution. “It’s not good for business if your school is linked to a religious leader.”

Robert Amsterdam, a bulldog international lawyer retained by the Turkish government to investigate the Gulen movement-links of U.S. charter schools, said that exhaustive research by his firm has defined the ties between the schools and the Gulen network. Repeating the Turkish government’s line, Amsterdam argues that the Gulen movement was clearly behind the failed coup.

“This is a very coordinated, organized threat to the United States,” Amsterdam said. “They’re taking a massive amount of taxpayer money. Many of the people operating in the schools have no idea how the organization really is operating.”

In glass cases at the entrance to Sonoran Science Academy – Tucson is a mountain of trophies, plaques, and citations in nearly every category imaginable: an award of meritorious achievement in the 2010 Arizona Academic Decathlon; a certificate of appreciation from the 2008 Tucson Rodeo Parade; a faded page from a 2003 edition of the Tucson Citizen that featured the school’s robotics program with the headline “Wired for Success.”

On one wall is a photo commemorating the governor’s visit to the school last year. The school’s mission statement is underneath: “To foster critical thinking, engaging all students in a rigorous STEM-focused, college-prep curriculum, delivered by a dedicated educational community that celebrates diversity, where students aspire to be tomorrow’s leaders.”

Around noon on a recent Tuesday, kids milled around a courtyard as a secretary commanded all middle-schoolers to gather for an assembly over the P.A. system. With such an ordinary school atmosphere, Sonoran Schools poses a question for parents and education experts: Does it matter if a charter school might be affiliated with a Turkish religious movement if students are receiving a high-quality STEM education?

Parents and alumni seem to be happy. Avery’s daughter, Bella, is now in sixth grade at Sonoran Science Academy – East, and her son, Logan, is in second grade. There has been no sign of Turkish influence or religious messages in the curriculum, aside from the language course, she said.

As of this fall, Avery is the vice president of the Parent Teacher Organization for SSA – East. The Gulen movement was totally unknown to her, Avery said.

“I don’t care where they’re from or what they believe or what they do,” Avery said of the Turkish staff. “I care about how they present themselves, how they treat others, and what they do for the students and the community.”

Turkish language is taught at four of the Sonoran Schools campuses, according to the administration. It’s the only other language offered widely in addition to Spanish, which is taught at all schools. One school offers American Sign Language. “Turkish was identified in the National Security Language Initiative program as one of several ‘critical need’ foreign languages for U.S. students,” Sonoran Schools said in a statement.

Even so, apart from the Turkish language class, the schools have introduced students to a group of dedicated Turkish educators and administrators.

Michelle Marquez, 22, is a 2014 graduate of SSA – Tucson, where she now works as a long-term substitute kindergarten teacher. She’s currently pursuing a graduate degree at the University of Arizona.

Before Marquez started attending Sonoran Schools, she couldn’t remember meeting someone from Turkey.

“I’ve learned to appreciate the culture that they bring to the school,” she said. “It’s not like they enforce anything on us or teach us about anything foreign. But when you have foreign teachers, you learn things from them. Just like you learn things from any teacher that you have – what they celebrate, what they like to do, how they live their life.”

Asked about the Gulen movement, with its mysterious Muslim preacher in exile and the alleged ties to her alma mater, Marquez started laughing as if in disbelief. “I have never heard of this ever,” she said.

The entrance to Sonoran Science Academy – Phoenix.

Joseph Flaherty

The political intrigue surrounding the Gulen movement is a story dating back to the creation of the Turkish republic nearly 100 years ago.

Modern Turkey was born from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, which collapsed in defeat to the Allies during World War I, and a war for Turkish independence led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. As the nation’s founder and first president, Ataturk sought to bury the imperialist sultanate that preceded him, curtail the Islamic religious sphere through Western-style secularist reforms, and reshape government and public life. The Arabic-style alphabet was officially abandoned. Imams became state employees, part of a newly created bureaucracy, the Directorate of Religious Affairs.

When the secular republic in Turkey was less than two decades old, Gulen was born in a village in rural eastern Turkey. Among the many mysteries surrounding the cleric is his age. His official birthdate is 1941, but he was probably born a few years before that, making Gulen roughly 80 years old. Confusion over Gulen’s birthday was supposedly due to a dispute between the registration official and Gulen’s father, which left the future religious leader unregistered with the state.

In most images, Gulen seems weary. The corners of his mouth are often downturned. He has liver spots and a white mustache, and usually wears a dark blazer with no tie. In some photos, he can be seen in the traditional knit cap worn by devout Muslim men. If you encountered Gulen amid daily life, he could be any elderly man sipping tea or waiting for the bus – hardly the inspiring figure admired by a legion of followers, or the villain regarded by the Turkish government as a megalomaniac.

A source of inspiration for Gulen was the influential 20th-century Islamic scholar Said Nursi, who believed that Islamic tenets and a modern scientific education could coexist and support each another. After taking the position of imam in the bustling city of Izmir on the Aegean Sea in 1966, Gulen gained a devoted following as he urged the pious to improve society through education. Inspired by his message, during the subsequent decades, Gulen’s followers established schools, test-prep centers, and universities in Turkey and abroad. They also built media organizations, charitable organizations, banks, and other business ventures.

All of this served to create a network of like-minded people while enhancing the reputation of Gulen, the charismatic leader who inspired such efforts. Eventually, Gulen’s following would grow to include millions worldwide.

“He’s viewed as tremendously wise, as the examples or legitimacy of his wisdom is exemplified in the success of the organizations,” said Joshua Hendrick, an associate professor of sociology and global studies at Loyola University Maryland and the author of Gulen: The Ambiguous Politics of Market Islam in Turkey and the World.

Gulen preaches an innocuous message of interfaith dialogue, tolerance, and education. For those who view Gulen favorably, the movement he leads is known as Hizmet, or service.

But experts on Turkish politics say that Gulen’s world network is actually concerned with acquiring power through loyal followers and a secretive organizational structure that resembles a cult.

“It’s long been suspected that the movement is interested in having a sole focus on making the Republic of Turkey more devout and culturally sort of religious,” said Sinan Ciddi, the executive director of Georgetown University’s Institute of Turkish Studies, “and thereby help raise a generation of pious individuals who are also raised in professional backgrounds that can serve in a modern economy.”

The Gulen movement has unique Turkish and Islamic roots, but it can be compared to the Moral Majority, Hendrick said, with its social-change agenda and a special focus on education and media. He likened its organizational discipline to that of the Mormon church. Hendrick was immersed in ethnographic fieldwork in Turkey for more than a year, where he examined the institutions of the movement, sometimes taking many months to gain access to Gulen sympathizers inside banks, media outlets, and companies.

Despite claims that the movement is apart from party politics, a central goal of the movement is “social power, very broadly defined,” Hendrick said, “Not just political power, not just economic power, but power defined as the ability to both cultivate and wield influence.”

Gulen’s critics believe that the movement wants to wield this influence to transform Turkey’s secular order established by Ataturk into a more openly religious society. Ciddi said, “I believe it to be harboring sort of what I would call clandestine intentions to achieve a religious and political ambition.”

Paragon Science Academy in Chandler.

Joseph Flaherty

Gulen moved to the U.S. in 1999, purportedly for medical treatment – he suffers from diabetes and heart problems. Fleeing Turkey also allowed him to escape the possibility of arrest by authorities who suspected the cleric held ambitions for an Islamist takeover. Shortly after he left, a video emerged that appeared to show Gulen plainly describing a subversive strategy to his followers.

“You must move in the arteries of the system without anyone noticing your existence until you reach all the centers of power,” Gulen said, instructing them to wait until they acquire “all the power of the constitutional institutions in Turkey.”

The year after he arrived in the U.S., a Turkish prosecutor charged Gulen in absentia with conspiracy to overthrow the government. He was later acquitted.

The same year that Gulen arrived in the U.S., the Daisy Education Corporation registered as a nonprofit. The first iteration of Sonoran Science Academy opened its doors in Tucson two years later.

Meanwhile, in Turkey, Erdogan’s conservative, Islamist-oriented Justice and Development Party (AKP) swept into power with a landmark victory in the 2002 elections. Erdogan and his political acolytes in the AKP had shared interests with members of the Gulen movement – namely, dismantling the influence of the secular military leaders over Turkish politics. The two groups were aligned for the first decade that the AKP was in power.

The Turkish military periodically carried out coups in defense of the nation’s secularist principles established by Ataturk. During his political ascent, the military was wary of Erdogan, the former mayor of Istanbul who was previously jailed for several months for reciting an Islamic-tinged poem at a 1997 rally. But Erdogan had a powerful ally in the Gulen movement. By this time, most observers concluded that many striving Gulenists, taking inspiration from Gulen’s sermons, had climbed to a variety of powerful positions within the state.

Beginning in 2007, Gulenists in the judiciary and police pursued members of the military in a series of byzantine investigations, which left the generals and the military severely weakened, the New Yorker reported. Some were given life sentences, accused of membership in a “deep state” organization seeking to destabilize the government.

But around 2013, then-Prime Minister Erdogan and the Gulen movement turned on each other. Exactly why the alliance broke down is unclear – the impending closure of Gulen’s test-prep schools likely contributed to the feud, not to mention the defeat of a common enemy in the secularist generals.

The power struggle exploded into public view during a corruption investigation in which family members of government ministers and businessmen tied to Erdogan were arrested. Erdogan blamed the investigation on Gulen, referring to “a state within a state.”

The Turkish government in 2016 branded the Gulen movement a terrorist organization with the acronym FETO, which translates to the “Gulenist terror organization.”

On the evening of July 15, 2016, the first sign of the chaos to come was when the military blocked the Bosphorus Bridge. Soldiers and trucks unexpectedly stopped traffic on the enormous suspension bridge, one of several routes across the churning waters of the Bosphorus, the waterway that separates Europe from Asia and connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. It was a Friday evening in Istanbul, and the city of some 15 million people pulsed with energy. Tanks and gunfire were about to shatter their night out.

During the hours that followed, Turkey plunged into terror as a faction of the military attempted to wrest control of the government in a coup d’etat. The Parliament building in the capital city of Ankara was bombed. Sonic booms from low-flying jets rattled windows. President Erdogan narrowly escaped capture by rebels in Marmaris, a coastal vacation town to the south.

In a surreal moment, Erdogan called into the Turkish CNN station through the FaceTime app on an iPhone, which the anchor held up to the cameras. The president exhorted Turkish citizens to take to the streets to protest the coup. Although some 250 people were killed, the plotters faltered. Their plans appeared to be hastily laid and were marred by critical errors, and soon, the coup was unraveling, hampered by civilian protest. By sunrise, the military coup had failed, and thousands of rebel soldiers were taken into custody.

When he arrived at Istanbul’s airport during the early hours of the morning, Erdogan left no doubt about the forces behind the coup. The soldiers were being directed from Pennsylvania, Erdogan said, implying that Gulen’s followers were responsible.

The populist strongman who had been in power for more than a decade at that point vowed to punish the Gulenist plotters. Erdogan called the attempted coup “a gift from God.”

Now a permanent resident of the U.S., Gulen has never returned to Turkey, despite the Erdogan government’s escalating calls for his extradition. “If he is sent there, very clearly, he will not get a fair trial,” said Y. Alp Aslandogan, the executive director of the Alliance for Shared Values, the most prominent Gulen-affiliated organization in the U.S. “It is like sending him to his death.”

Y. Alp Aslandogan, the executive director of the most prominent Gulen-affiliated nonprofit in the U.S.

Courtesy of the Alliance for Shared Values

Gulen lives at an isolated compound in rural Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania. Known as the Golden Generation Worship and Retreat Center, the 25-acre property includes several plain, unadorned houses, a community center, a mosque, and a security gate, all surrounded by woods. Gulen, who is unmarried, gives sermons to visitors typically twice a week when they visit the center for prayer or meditation, but he seldom grants interviews.

Aslandogan, who came to the U.S. in 1991 as a graduate student, is a conduit to the reclusive preacher. As the head of the Alliance for Shared Values, an umbrella nonprofit, Aslandogan said that the organization serves as “an authentic voice for the Hizmet participants in the United States.”

He said that he was not personally familiar with the people working for Sonoran Schools. “It’s not that I’m trying to hide anything. I just don’t know the people involved,” he said. At the same time, Aslandogan argued that if people working for the charter network are Gulen sympathizers, they probably believe in serving their community through education. “In that sense, at the personal, spiritual level, or philosophical level, you might say they have a personal link,” Aslandogan said. “I don’t see any problem with that.”

He suggested that the fault is with people probing ties to the Gulen movement who ask vague questions.

“‘Is your school linked to the movement?’ That is an ambiguous statement. If they ask, ‘Are you personally inspired by the movement or Mr. Gulen?’ That’s easier, this person can say, ‘Yes, I am personally inspired,’ or not,” Aslandogan said. “I think people are trying to avoid ambiguity,” he added.

If schools cover up some affiliation with the Gulen movement, Aslandogan argued they face opponents like Amsterdam who are trying “to depict these schools, or any institution where Gulen sympathizers are active, as a threat to American way of life or abuse of American taxpayer money, or something like that.”

Members of the Gulen movement who have gravitated toward establishing public charter schools, Aslandogan suggested, have done so to serve disadvantaged kids who might not be able to afford a high-quality private school education.

Parents who might be concerned to hear that a socio-religious movement is behind an Arizona charter network would do well to study the Gulen movement, Aslandogan argued. He reeled off several of the group’s purported tenets: love of science, interfaith dialogue, increased opportunities for women. Gulen, he said, has been a proponent of democracy and secularism.

“This is a group that I think they should find immensely valuable if they find any participants, any sympathizers involved in education,” Aslandogan said. “They have an asset for this country.”

The entrance to Sonoran Science Academy – Phoenix.

Joseph Flaherty

Shortly after the one-year anniversary of the failed coup in Turkey, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey paid a visit to Sonoran Schools.

When he arrived at the campus of Sonoran Science Academy – Tucson on August 21, 2017, two Turkish administrators greeted him. Fatih Karatas, the charter network’s chief executive, wore a colorful tie covered with molecules and a twisting helix. Karatas was joined by Adnan Doyuran, the Sonoran Schools associate superintendent and principal of the middle and high school. Balding with glasses, Doyuran has a Ph.D in physics from Stony Brook University and happens to be an expert on particle acceleration and free-electron lasers. He shook hands with Ducey.

Ducey is a school-choice advocate, making Sonoran Science Academy a natural pick for a visit from the governor during a back-to-school tour. In a promotional video produced by Sonoran Schools, the governor praised the school’s award-winning robotics program, and marveled at a demonstration of a championship robot. Like any visit from an elected official, the tour was a clear badge of approval.

“This is something that’s working,” Ducey tells Karatas and Doyuran in the video, standing in a school entryway. “We need to do it more often, in more places, for more of our kids. It doesn’t work without leaders and teachers like you have here, though.”

Karatas and Doyuran are part of the unusual number of Turkish staffers who work for the charter network and serve on the governing board of the charter holder, Daisy Education Corporation.

Out of a dozen top administrators of Sonoran Schools, four of them are apparently Turkish: CEO Fatih Karatas, associate superintendent Adnan Doyuran, CFO Tuncay Celik, and curriculum director Tolga Ozel. (Like other Sonoran Schools staffers, at least Doyuran and Ozel were educated in Turkey.) And like other alleged Gulen-affiliated schools in the U.S., Sonoran Schools appears to rely heavily on specialty-worker visas to recruit employees from overseas.

The Daisy Education Corporation has received certification for at least 149 H-1B visas since 2009, according to data from the U.S. Department of Labor. Of these labor condition applications submitted for nonimmigrant workers, 68 have been for new employment, as opposed to a change in employer or the continuation of previously approved employment. Not every certification for an H-1B visa by the federal government means that a foreign worker was hired, but the number of H-1B applications by the chain may be even higher because of variations on the name of the charter school listed as the visa sponsor.

Other traditional and charter schools don’t approach Sonoran Schools’ use of H-1B visas.

Another recognizable and rigorous charter network based in Arizona, Great Hearts Academies, has received certification for H-1B visas on just three occasions during the same time period. Even the Phoenix Union High School District, with a student population over 10 times the size of Sonoran Schools, has received only 46 H-1B visa certifications over the last decade, less than a third of Sonoran Schools’ total.

In addition to the H-1B visas sought by the network, Sonoran Schools has applied for permanent labor certification on at least 14 occasions over the last decade. According to federal data, the Daisy Education Corporation has sought to certify for green card status mostly employees from Turkey, except for two people from Turkmenistan and one from Kyrgyzstan.

The charter network said that only three staff members out of 254 are on H-1B visas, and added that multiple labor condition applications (LCAs) are filed for the same position, or are filed when an employee changes jobs. “The gross number of approved LCAs is always higher, sometimes by a significant factor, than the actual number of workers who work at an employer in H-1B work status, based on an approved LCA,” Sonoran Schools said.

At the same time, paradoxically, Sonoran Schools argued that a drought in qualified educators has forced them to use the H-1B program.

“It is irrefutable that beyond a general teacher shortage, there is also a critical shortage of effective STEM educators,” Sonoran Schools said. “Across the nation, schools and districts report difficulties recruiting and retaining knowledgeable STEM teachers and many have turned to international recruitment to address this shortage.”

The charter network did not address its practice of applying for permanent residence for employees from Turkey and Central Asia, only saying that the schools have a “vested interest to retain all highly effective staff.”

Experts on the Gulen movement say affiliated charter schools seem to have another vested interest: recruiting fellow members of the movement from Turkey.

“Most of the Turkish teachers are graduates of the Gulen movement schools in Turkey,” said Taspinar, the Brookings Institution fellow. “And they have sympathy for the Gulen movement. They’re conservative people. They’re pious people. And there is nothing wrong, in my opinion, with that except that there is this culture of secrecy.”

Phoenix New Times reviewed the publicly available resumes on file at all six Sonoran Schools academies for the 2018-19 school year. Among those employees, 31 staffers hail from Turkey, three from Kyrgyzstan, and one from Turkmenistan. With the exception of SSA – Davis-Monthan, at every Sonoran Schools academy, either the principal or vice principal is Turkish. At the Chandler academy, at least 10 employees are of Turkish origin based on their names and educational history in the country. (Sonoran Schools could not say how many staffers hold Turkish citizenship.)

Several of the Turkish teachers and administrators have connections to other alleged Gulen schools and institutions. Doyuran, who serves as the principal of SSA – Tucson’s middle and high school, previously worked at the Lotus School for Excellence in Colorado from 2008 to 2013, according to his resume. Before that, he served as dean of academics and physics teacher at Magnolia Science Academy in California. Researchers suggest both charter organizations are linked to the Gulen movement. The dean of academics at SSA – Tucson, Recai Yilmaz, worked for the Magnolia charter network and the Coral Academy of Science in Las Vegas.

Their trajectories are almost identical to Erdal Kocak’s, the principal of SSA – East, who was the principal of Magnolia Science Academy from 2009 to 2012. Prior to joining Sonoran Schools, Kocak traveled widely, working in K-12 schools from Australia to China to Albania.

Many current Sonoran Schools employees worked at Magnolia Science Academy schools before moving to Arizona. Recently, the California charter network of 10 science-and-technology-focused schools was rattled by audits that questioned financial practices and the hiring of Turkish staff from abroad, and two years ago, the Los Angeles Unified School District voted to close three Magnolia schools. However, the decision was overturned on appeal by the board of the L.A. County Office of Education.

In 2010, then-Sonoran Schools superintendent Ozkur Yildiz denied any institutional affiliation with the Gulen movement in response to questions from the Tucson Daily Star, but he acknowledged that he was personally familiar with Gulen. Some Turkish teachers may be “inspired” by the religious leader, he said, given the preacher’s notoriety in Turkey.

Like other public charter schools in Arizona, Sonoran Schools is free to attend; the network receives funding from the state on a per-student basis. In 2018, the six Sonoran Schools academies received a total of $16,171,980 in funding from Arizona and $2,397,948 from the federal government.

But the presence of Gulen-affiliated charter schools in the U.S. charter sector has contributed to swirling allegations, some conveyed through whistleblowers discovered by Amsterdam, regarding a kind of tithing that takes place using publicly funded salaries.

According to Hendrick, members of the Gulen movement, including teachers at Gulen-affiliated charter schools, give a portion of their income, known as himmet, back to the Gulen movement, usually cultivated via a regional arm of the network such as an interfaith dialogue nonprofit or an educational consulting firm.

Like much of the Turkey-Gulen conflict, the allegations resemble a plot device in a pulp thriller: Turkish teachers at U.S. charter schools contributing a portion of their taxpayer-funded salaries to a transnational religious movement with murky goals. These alleged kickbacks are supposedly donated from employees personally, and not from the charter organization, so they wouldn’t surface in the school’s financial records.

“Because it’s under the table, because it’s somebody’s personal choice or framed as such, it’s very difficult to pin down anything nefarious,” Hendrick said. “But again, I will say this: If you’re a member of the Gulen movement, you give himmet. That is in fact an identifying characteristic of being a member of the Gulen movement.”

Sonoran Schools denied that any employees are asked to or required to give money to the Gulen movement. “DEC does not inquire about or track and has no interest in an employee’s personal beliefs or views,” the charter school said. “It does not ask, encourage or require its employees to provide monetary or other support to any entity, nor has it ever done so.”

Left: Fatih Karatas, the CEO of Sonoran Schools, at a December 6 governing board meeting for the charter network. To the right is Tuncay Celik, the charter network’s CFO.

Joseph Flaherty

Ever since the coup attempt, the Turkish government has lashed out at enemies, real or imagined, in a purge that cuts across all segments of society. The reported numbers of arrests, detentions, and firings are hard to comprehend: over 100,000 fired from public-sector jobs in the judiciary, police, or education and tens of thousands arrested, often with spurious evidence tying them to the Gulen movement. A state of emergency which had been in place since the attempted coup was finally lifted this summer.

Meanwhile, Erdogan has continually demanded that the U.S. extradite Gulen, and the intrigue over Gulen has even embroiled a former player in the White House.

President Trump’s former national security adviser Michael Flynn, already a target of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election, may face more consequences as a result of Turkey’s campaign against Gulen.

Newly unsealed indictments say that two former business associates of Flynn engaged in a conspiracy and acted as unregistered agents of the Turkish government when they worked with Flynn’s firm to conduct an influence campaign against Gulen in 2016. Even more bizarre is the allegation, reported by the Wall Street Journal, that Flynn and his son may have planned to kidnap Gulen to return him to Turkey on a private jet.

In another front in the war against Gulen, since 2015, the Turkish government has retained attorney Robert Amsterdam’s international law firm to investigate Gulen-affiliated charter schools. Last fall, his firm Amsterdam and Partners published a tranche of information on Gulen-affiliated charter schools located in many different U.S. states in the form of a free ebook.

All of the Gulen-affiliated charter schools work in the same way, according to Amsterdam, in a cycle fueled by taxpayer dollars: Turkish employees recruited from abroad, contracts doled out to affiliated firms, and money raked from teacher salaries and distributed to the wider network as tithes. Thanks to their research, he said, people are finally taking notice.

“It’s frightening how little oversight there is in respect to the power of this organization over almost 80,000 students in the United States,” Amsterdam said.

He dismissed the matter of the Turkish government’s payments to his firm (“It is the most unprofitable activity the firm has even undertaken, outside of pro bono work,” Amsterdam claimed) and said they investigated independently from Erdogan’s government.

“There’s a difference between a religious organization and a political organization with the goal of the overthrow of a government,” Amsterdam said.

Sonoran Schools are hardly the only charter school system in Arizona with loose ties to a certain religious group. Accusations of Christian faith-based teaching have dogged Heritage Academy, and American Leadership Academy is said to have ties to the Mormon community. However, as long as they do not openly teach religion, they are free to accept public dollars.

Jim Hall, a charter school watchdog and the founder of Arizonans for Charter School Accountability, said that Arizona’s permissive charter law allows virtually anyone to establish a charter school.

Seated in his shoebox office near Metrocenter where he pores over financial records, Hall was nonchalant about the allegation that Gulen schools operate in Arizona.

“There’s charter schools here that cater to the LDS community – not explicitly, but implicitly – and something like Gulen can come, too, and as long as they come with a business plan and fill out all the paperwork, there’s really nothing that would prevent this,” he said.

From a fiscal and regulatory standpoint, Hall said that Sonoran Schools appears to be a respectable charter operator in a flawed system. The academies, three of which are A-rated, have solid financials, good test scores, and a diverse student population.

“Compared to other charters, they just aren’t on the radar in terms of graft or in terms of not spending their money in the classroom,” Hall said.

When asked about the extraordinary H-1B visa applications and an apparent flow of Turkish teachers to Sonoran Schools, Hall said, “What we say about charter schools is that it’s legal. And so whether it’s right, ethical, whatever, isn’t really the concern when you’re talking about charter schools.”

The question of whether parents should send their kids to Sonoran Schools leads to a familiar problem that happens when you peel away at an organization to examine the ideology underneath. Because of Arizona’s charter school environment, the decision to attend a Gulen movement-

affiliated school is akin to other politicized consumer choices, where an entity with murky goals and questionable ethics offers a desirable product.

Hendrick offered a comparison to fast food. “Some people have a problem with eating Chick-fil-A because it’s affiliated with organizations that have a particular political agenda,” he said. “Other people say, well, the chicken sandwich is great, so I’m still gonna eat it.”

Meanwhile, on a recent Wednesday evening, Jessica Avery and her daughter Bella were studying together and trying out some Turkish phrases while Avery cooked dinner. “She was trying to teach me how to say, like, ‘My name is,’ and to respond when she said, ‘Hello, how are you?'” Avery recalled.

The language is very different, but fun to practice, she said. “It’s something I would’ve never even thought they would have the opportunity to learn,” Avery said.

With the sixth-grade year halfway over, her daughter plans to continue studying Turkish.