Jim Louvau

Audio By Carbonatix

Next to Apache Lake, the southern bank of the Salt River rises in a palette of tans and browns dotted with green stubble. Partway up the slope, the summer desert hues stop abruptly at a horizontal fire line. Above it, the land converts to a purplish-black – summer desert, singed by wildfire.

The Woodbury Fire, which began in early June in the Superstition Mountains, is now almost fully controlled. As of July 5, when the U.S. Forest Service delivered its final update on the fire, 90 percent had been contained. No one died or was injured, although residents in a few areas were ordered to evacuate, and while the fire was large, at nearly 124,000 acres, it was not particularly intense, as wildfires go. The vast majority of it burned at a severity deemed low or very low.

But as the most immediate threats die down with the fire, the lasting consequences have yet to set in. Around the Salt River, of particular concern are the potential impacts of the lowland Woodbury Fire on the freshly vulnerable river. Once monsoon season begins, torrential rains could potentially wash ash, soil, charred remnants of cacti and brush, and any number of other things out of the burnt watershed and into the river.

“That’s a very vulnerable time, after a fire,” said Sheila Murphy, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who is based in Denver. “In Arizona, you’ve really got to worry around monsoon season.”

The water of the Salt River travels through a series of reservoirs, dams, and canals before reaching Valley cities like Phoenix and Scottsdale, which treat it before distributing it to people, homes, and businesses. The more murky and contaminated the water, the more chemicals, and money, needed to fix it.

Now, scientists and water managers are in wait-and-see mode. Monsoons are unpredictable, and while experts can use past experience to speculate about the possibilities, no one knows how severe the water-quality problems following a monsoon could be. The season for these summer storms begins in June, but the Valley has yet to have its first this year.

“We’re not entirely sure what Mother Nature’s going to do,” said Mike Ploughe, an environmental compliance scientist with the Salt River Project, which manages the water supply from the Salt and Verde rivers. The primary concerns are organic materials – charred material, other debris – and nutrients that could increase the turbidity of the water or fuel the growth of algae. But outcomes also depend on where the rain falls, and how heavily, he said. In the short term, little can be done to prevent any potential devastation of the water supply.

Last year, the U.S. government’s climate assessment noted that in the Southwest, climate change is increasing wildfires in a way that is “statistically different from natural variation,” and that among the risks of these changes are “post-wildfire effects on ecosystems and infrastructure.”

Roosevelt Lake, the largest reservoir on the Salt River.

Jim Louvau

Waiting for the Rains

Ploughe spent the morning of July 3 at Apache Lake, collecting samples of clear water to establish baseline levels of water quality before the monsoons come. Apache Lake is the second-biggest reservoir on the Salt River, directly downstream from Roosevelt Lake, the largest. Downstream from Apache Lake is Canyon Lake, then Saguaro. After Saguaro, the water is diverted into canals.

“The whole system is clean right now,” Ploughe said shortly after returning from Apache Lake.

This summer is the first time SRP has taken samples rigorously from the smaller reservoirs below Roosevelt Lake, Ploughe said, and it is taking them because of the Woodbury Fire. Runoff from past wildfires has typically emptied into Roosevelt Lake, which has a storage capacity massive enough to weaken the intensity of any contamination.

Ploughe and his colleagues at SRP hope that the combined capacity of Apache, Canyon, and Saguaro lakes will do the same after the Woodbury Fire. That fire burned at a low elevation, coming within a few miles or less of Apache and Canyon’s shorelines, and potential runoff from the burned area will likely empty into those lakes, which are much smaller than Roosevelt.

Now, SRP wants to test those smaller lakes’ ability to handle any contamination resulting from runoff from the burned desert, which is unlike the forested areas that fires have consumed closer to Roosevelt.

“We really don’t know what kind of loading we’re going to get in the lakes. It’s a different kind of landscape that’s burned,” said Ploughe, naming grasses, desert brush, and cactus. “You don’t have the organic mass that you’d have in a ponderosa, pinyon-type forest,” he added.

Ploughe expected at least some changes in turbidity. How long those changes will take – a few days, a week, longer – also remains to be seen, as they depend on where the rain falls, and how much. If a light rain hits a small area of the burned watershed, the reservoirs might be affected minimally. If monsoon rains are heavier and more widespread, the consequences are likely to be greater.

Luckily, Ploughe pointed out, the Woodbury Fire was primarily in a wilderness area, one that has not been heavily mined or otherwise touched by industrial activities. When it comes to chemicals potentially entering the water supply, Ploughe said, “I don’t foresee a real issue there.”

About 80 to 85 percent of the Woodbury Fire fell within the Salt River’s watershed – the area from which water runs off the land and into the river – although the fire itself constituted only about 3 percent of the watershed, according to Charlie Ester, surface water resources manager for SRP.

Ester was hopeful that once the monsoons arrive, the Woodbury Fire would not prove too destructive.

The hotter a fire, the more hydrophobic the soil becomes, and the more rain it will repel, sending silt and sediment gushing downhill rather absorbing the water as it falls. Most of the Woodbury Fire maintained a relatively low intensity – 75 percent was either low, or very low, or unburned – in part because there wasn’t much desert vegetation to burn, and so the runoff might not overwhelm the reservoirs, Ester said.

When fires burn at a low severity, anywhere from 10 to 30 percent of the ground cover is burned, and “hydrophobicity is generally absent,” according to the U.S. Forest Service, meaning the ground is more likely to absorb water.

The Forest-Water-Fire Connection

Scientists still understand relatively little about the mechanisms linking wildfires and water quality, but they do know that in watersheds, healthy forests and ecosystems are crucial.

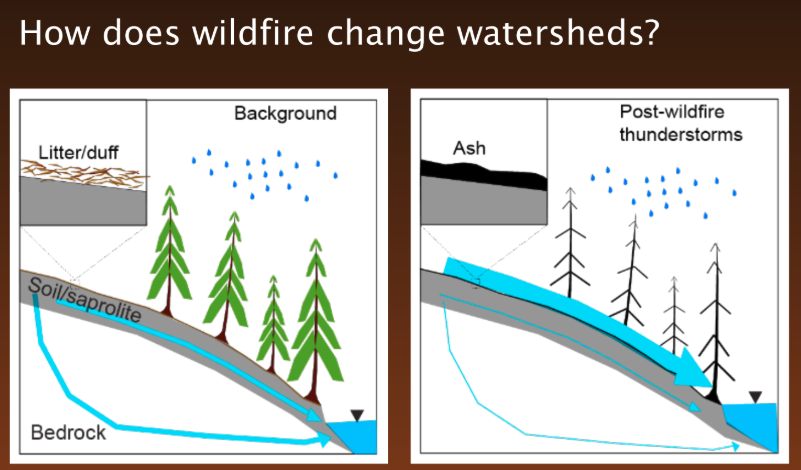

“Forests are both a filter and a sponge,” said Murphy, the USGS hydrologist. Forests soak up water and allow it to filter slowly into streams and waterways. When wildfires tear through, they damage the forest’s ability to absorb and process the rain that falls afterward.

“That is a very vulnerable time, after a fire… In Arizona, you’ve really got to worry around monsoon season.” — Sheila Murphy, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey

Little research existed when she started in the field about a decade ago, Murphy said. Since then, the science has developed, but many questions remain unanswered.

“We need to better understand the process in different areas of the country and different land covers,” Murphy said.

Those factors including the timing and type of precipitation, the location, land cover, land grade, and previous land uses. Murphy said she is trying to study weather patterns that impair water quality after wildfires.

One study that Murphy led, published in 2015, found that the most substantial changes to water quality in one post-wildfire area in Colorado came after intense rainfalls. They concluded, too, that water quality can be affected for years after a wildfire.

A diagram from a study Murphy worked on shows wildfires change the relationship between the ground and water, so that rainfall slides off of burned land rather than being absorbed.

Courtesy of Sheila Murphy

A Shock to the System

In Arizona, past, severe wildfires have temporarily brought down the SRP water system.

In May 2012, the Sunflower Fire crackled through about 17,500 acres of the Tonto National Forest. Subsequent rains sent charred debris down Sycamore Creek, which feeds into the Verde River, which in turn converges with the Salt River below the reservoirs, shortly before the water is diverted into canals that go to cities.

“I remember, after the Sunflower Fire, the turbidity levels were just astronomical,” Ester said. The water was so murky that SRP had to take water from the Central Arizona Project, which brings Colorado River water to central Arizona, in order to dilute the effects.

Brian Biesemeyer, the director of Scottsdale Water, said that Scottsdale operates the first municipal water treatment plant to receive water from an SRP canal, and that after the Sunflower Fire, the plant had to shut down because the water contained too much organic material to be treatable.

That was one of two times that wildfires forced the plant to close, Biesemeyer recalled. The other followed the 2011 Wallow Fire, which scorched more than 522,000 acres in Arizona.

Scottsdale doesn’t receive all of its water from SRP; it also gets water from the Central Arizona Project and from groundwater, so when it can’t take water from the Salt and Verde system, it relies more heavily on those other sources.

But when it can treat water that contains organic materials from wildfire runoff, the treatment is more complicated. It also costs more, in part because the city has to add more chemicals to remove extra carbon or excess silt.

“Those costs are passed on to the customers, and I don’t have any specifics on how much that is,” Biesemeyer said.

The Woodbury Fire, seen on June 28, 2019, burned close to Apache and Canyon Lakes on the Salt River.

Jim Louvau

Back to the Forest

Today, Biesemeyer, Ester, and Ploughe, along with others who manage, measure, or plan the Valley’s precious water supply, can do little about the Woodbury Fire and the coming monsoons.

They say they’ve come to recognize the importance of healthy forests for water quality, and they’ve begun chipping in to bolster forest management and restoration activities that they hope will help reduce the severity and spread of wildfires and mitigate the consequences for water quality.

Scottsdale Water gives $50,000 a year to the Northern Arizona Forest Fund, Biesemeyer said. SRP, meanwhile, partners with the affiliated National Forest Foundation, the U.S. Forest Service, the Arizona Forestry Department, and other groups – it’s giving $400,000 to The Nature Conservancy – to thin and restore forests in northern Arizona, although those efforts are still in the early stages.

In 2013, SRP also began monitoring precipitation and stream flow in its watershed areas, using cameras and other tools to track changes in water flows, especially as forest restoration efforts take root.

Lee Ester – elder brother to Charlie, and SRP’s water measurement chief – is in charge of that project. He said that in areas devastated by especially fierce wildfires, like the 2002 Rodeo-Chediski Fire, the watershed is still recovering.

“They were really hot fires. There’s almost no tree life remaining,” he said. “So it’s not really understood, at least at SRP’s level, what the recovery level of that watershed will be. Certainly a very long time.”