Cera Murphy stood on the steps of the Maricopa County Superior Courthouse, holding her foster care license and a lighter.

It was an early afternoon in June 2018 and Murphy, a nurse in Phoenix, had been a foster parent for almost five years. She had just finished adopting her third child, giving all the children under her roof a safe, permanent home. She wanted to help more children. But she was also fed up with a system flooded with inaccessible caseworkers, frustrating appeals, and unsupportive staff.

So, with a borrowed lighter from her licensing worker, she set the paper ablaze.

“I was so done,” she said in a recent interview. The solo act was her symbolic "middle finger" toward the Department of Child Safety, she said.

Murphy is far from alone in terminating her license — about 2,000 foster parents in Arizona made the same decision last year.

The state's child welfare system is prepared to handle a certain number of such losses. Agencies are constantly recruiting new prospective foster parents to apply, and can provide emergency beds and shelters if all else fails. Ideally, as some foster parents drop out of the system, new applicants will fill in to take their place.

But in part because of problems with foster parent recruitment and retention documented in a recent statewide audit, Arizona’s child welfare system has lost more licensed homes than it has gained in 2018 and 2019, according to DCS data.

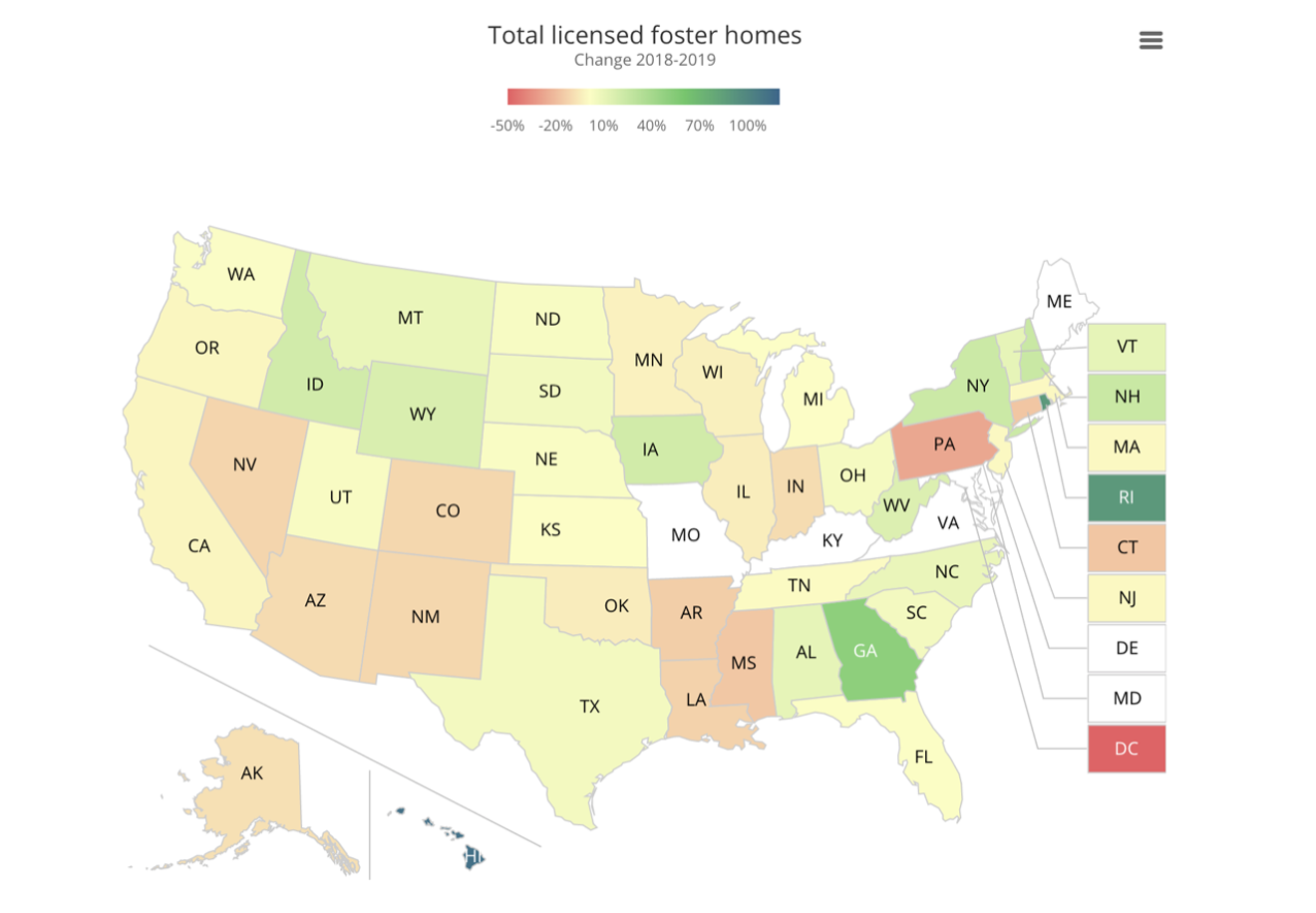

A new national report released October 10 by the Chronicle of Social Change puts that finding into startling context. Arizona lost 10 percent of its licensed foster homes between 2018 and 2019. That’s about 400 in total. Other states have faced losses, too, but few as severe as Arizona — only nine states lost a larger percentage of homes in the same time period, according to the study. That raises questions about why Arizona in particular is hemorrhaging foster parents, and how it can better recruit and retain families to ensure all children get care.

This isn't the first time Arizona's child welfare system has faced high demand and not enough foster homes. Back in 2015, when Arizona was inundated with some 18,000 children in the state's care, the crisis got so bad that kids frequently spent nights in DCS offices. Now, there are only about 14,500 children in Arizona's child welfare system, according to DCS, but experts say there are still important gaps.

Torrie Taj, CEO of the nonprofit Child Crisis Arizona, said the system always needs more foster homes than kids, because foster parents sometimes prefer a certain age, gender, or number of children. That means certain groups — often older kids — end up in group homes or other temporary housing instead of with long-term families.

“Our pipeline isn’t full enough in order to keep up with the demand,” Taj said. “We’re definitely feeling it.”

Taj said her agency used to get about 10 new families signing up to foster children each month. Now, they average 7.2.

Last month’s report by the Auditor General’s Office found that DCS customer service issues, as well as foster parents not getting enough information from the state about the children in their care, had become barriers to recruitment and retention of foster parents.

Former foster parents who spoke with Phoenix New Times had some of the same complaints.

Murphy said that in her time as a foster parent in the system, she was often shuffled between case managers and licensing workers, some of whom were unresponsive.

“The case managers just weren’t accessible,” she said. “I never felt supported.”

Dina Uraine, a foster mom who adopted her daughter, Silencia, in early October, notified DCS that she would be terminating her license this week.

While she closed her license largely because of the adoption and plans to move out of state, she said her experience with DCS was fraught with challenges.

Uraine cared for Silencia’s biological brother for a while, but wasn’t given clear information about his medical needs and challenging behaviors. When she decided to take him off a medication that the case manager told her “was basically a gummy vitamin,” the boy began having angry outbursts. Eventually, she had to disrupt his care, and he remains in Arizona's child welfare system.

“I can’t tell you how many holes in walls and doors I’ve had to patch,” Uraine said. “If I couldn’t laugh at it now, I’d probably cry.”

Like other foster parents interviewed for last month’s audit, Uraine said she never received a complete information packet about the child, even though such information is required in the state under a law called Jacob’s Law.

“I don’t know a single family who’s not frustrated with DCS,” she said. “Like, literally every single one who’s involved with foster care is frustrated with them for one reason or another.”

Still, the drop in licensed foster homes this year could be in part because of more families adopting children who were placed with them on an emergency basis when the system was so overburdened a few years ago, Uraine said.

Advocates for the foster care system say there are plenty of good families and caseworkers who want to help children, but bureaucratic problems can stand in the way.

The data shows that month to month, Arizona’s child welfare system is still losing families. In August, the most recent month for which data is available, 107 new licenses were issued, but 181 were closed.

Darren DaRonco, a DCS spokesperson, said the number of licensed homes right now doesn’t represent a severe shortage. He also said the agency has several campaigns in the works to recruit new families.

Despite her frustration with DCS, Murphy still spends time answering questions on foster parent boards and demystifying forms and processes for new foster parents.

She underscored how many people genuinely want to improve the lives of foster children, and how important the system, however fraught, has been for the children and families involved.

“I’m still kind of helping advocate for people,” she said.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]