“Where’ve you been?” my former co-worker asks.

He is a tall, ruddy, smart-ass Irishman who happens to be the head of security at the big public library where I used to work. I was a library assistant. Our banter, back then, usually centered around our shared belief that we could write a killer television show called The Library. Think about the cast of characters; on the one hand you have “the librarians” — some of whom are the most resourceful, socially awkward, creative people you are likely to meet. Then you have a wide-range of “regulars” — people who reflect the ways in which libraries have become the ad hoc container for many of our country’s gaps in social services.

In a nutshell, you have socially awkward people dealing with the extremes of social behavior, and with shrinking funds. Then, of course, you have “the guards,” who are the intermediaries and observers of it all.

I’ve been thinking about our television show recently because there are mornings when I wake up, scan the headlines, and feel like I’m living in Bizarro World, the fictional planet referenced in DC Comics where everything is flipped on its head or opposite of one’s expectations. The Bizarro Code states, “Us do opposite of all Earthly things! Us hate Beauty! Us love Ugliness! Is big crime to make anything perfect on Bizarro World!”

We are living in a time when a foreign government has attempted to interfere with our elections, where the line between fact and opinion has been blurred, where marginalized groups fear greater marginalization, and where we are in the midst of a cultural conversation about what’s real and what’s fake. It’s disorienting. People are concerned. There is a feeling in the air. Real is good, so where do I reliably find it?“Having information matters; having the right information matters more.” - Lee Franklin

tweet this

I’ve tried to come up with an answer, an antidote, and here’s what I’ve got: I still believe in libraries and archives.

I know I’m not the only one looking to regain my bearings. As Lee Franklin, community-relations manager for the Phoenix Public Library, said to me the other day, “Having information matters; having the right information matters more.”

So, I wonder, can informing ourselves be an act of resistance to the Bizarro Code? I see groups popping up, making New Year’s resolutions, forming book clubs to understand the intersectionality of history and politics. There’s Reading for the Revolution on Facebook; Pantsuit Nation has circulated a reading list; Public Books has published a very thorough Trump Syllabus 2.0 assembled by historians N.D.B. Connolly and Keisha N. Blain; and Grace Bonney, founder of the design blog Design Sponge — which reaches more than 1 million readers per day — posted a picture of a stack of books on Instagram saying, “I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways in which history repeats itself ... I want to listen to and absorb as many first-hand accounts and different points of view as possible.”

On Bonney’s current reading list: Women, Race, and Class by Angela Y. Davis, and Freedom’s Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement from 1830 to 1970 by Lynne Olsen.

The idea of wanting to hear first-person accounts, understand why others with different life experiences feel as they do, and embed oneself in something “real,” got me wondering. Who better to talk to than information workers, librarians, and archivists? When so many of us are looking for tangible examples of fact that we can hold up and examine, why not ask the people who know how to find things? What issues are they thinking about right now? Could they share some of the gems in their collections, and what might these treasures tell us about the times we’re living in, and where we came from?

And so I headed out into the proverbial stacks. I focused on archival collections in the Phoenix metro area, hoping to learn about materials that could give a broader historical perspective. I tried to keep in mind that the main difference between libraries and archives is, essentially, that library materials are published, and therefore tend to be more widely available, while archival materials are, by and large, unpublished, more unique, and can include documents, letters, objects, organizational records, photographs, ephemera, et cetera.

What I discovered: There are many illuminating, thought-provoking treasures right beneath our noses — some serious, some lighthearted — illustrating our shared human history.

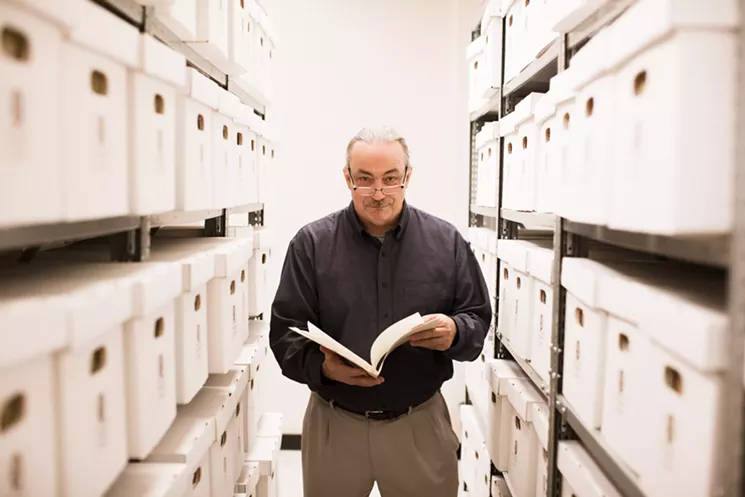

Rob Spindler, university archivist and head of the Archives and Special Collections at Arizona State University Libraries.

Randi Lynn Beach

ASU’s holdings are vast. We’re talking 28,000 linear feet of archival material, 1.2 million photographs and growing. The Archives and Special Collections department operates six different repositories: the Arizona Collection, the Chicano/a Research Collection, University Archives, Benedict Visual Literacy Collection, Special Collections, and the Child Drama Collection.

“What we do with archives is tell the story behind the headlines,” Spindler says. “Archives give us detailed information about ‘why’ and ‘how’ things came to be the way they are today.”

The main challenge one is likely to find is the sheer volume of material. With a collection as big as this one, “We can’t digitize it all,” says Spindler, “and so what you really want to do is to be able to give exemplars of what can be done in these collections and excite people to come in and actually work with them.” About a third of visitors to the Archives and Special Collections at ASU are members of the general public.

People are still coming in to study Barry Goldwater. “There are a lot of very interesting parallels between this past presidential election and the election of 1964,” says Spindler, given the fact that that election was the last time a major political party produced so polarizing a candidate. There was even a magazine, he adds, that published a poll of psychiatrists who were asked if GOP candidate Barry Goldwater was “psychologically suited to be the President of the United States.”

Spindler’s referring to the legal case in which Goldwater sued Ralph Ginzburg, editor of Fact magazine, for defamation over a 1964 article entitled, “The Unconscious of a Conservative: A Special Issue on the Mind of Barry Goldwater.” Fascinating stuff, to be sure. News website Slate recently contacted the ASU archives looking for materials related to the case for its podcast Whistlestop. Spindler and his team digitized documents and sent them to Slate for the show last September.

Recently, Arizona Secretary of State Michele Reagan announced a partnership between the Arizona State Archives and Ancestry.com, making a group of Arizona historical record collections available online and free to residents of the state, including Arizona territorial census records during the years 1864 through 1882.

“We’ve seen amazing growth in the number of people digging into our digital collections,” Reagan said in a release. “Over the last couple of years, we’ve prioritized the digitization of historical records and archival material to make them available to people around the state, not just those who live in Phoenix.”

Nancy Liliana Godoy-Powell, archivist and librarian of the Chicano/a Research Collection at ASU, and advocate for underserved communities in libraries and archives. She is the recipient of the 2017 Arizona Humanities Rising Star Award.

Randi Lynn Beach

Nancy Liliana Godoy-Powell, archivist and librarian of the Chicano/a Research Collection at ASU, says, “I feel like there is a hunger to hear first-person stories. Especially from communities that have been marginalized for so long, especially in Arizona, seeing that the Latino community makes up almost half of the population in Arizona (which is the sixth-largest population in the United States).”

Rest assured: These stories aren’t going anywhere.

To get a perspective from outside the state, I spoke with Bonnie Gordon of the all-volunteer-run Interference Archive in Brooklyn, New York, who said that documentation is nonerasure. It’s important that their archive, whose mission is to explore the relationship between cultural production and social movements, is embedded within the community and used by community members, “It’s important to think about the past and what we want today: the stories of grassroots struggles, and linking them to other struggles.” At Interference Archive, they gather cultural ephemera: posters, pamphlets, flyers, photographs, audio recordings, et cetera, to tell the history of people mobilizing for social transformation.

This attitude of openness may seem like an outlier, but I’ve discovered there is a willingness to share and collaborate even among more traditional archival spaces. Technology is making this possible.

“The goal is: If we can clear rights, and we can digitize it, and describe it so people can find it, we’re putting it up in the ASU Digital Repository,” says Spindler. “And I think that represents a huge sea change in the ways archives operated.”

In many ways — some subtle, others more direct — we are engaged in archiving our own lives all the time now anyway through social media, particularly young people, but they haven’t perhaps made the mental shift where they are thinking about that documentation in terms of their family story, or their community story, or their roots.

Libby Coyner, archivist at the Arizona State Archives, and Vice President for the Arizona Archives Alliance.

Randi Lynn Beach

“That’s a really interesting idea,” says Coyner, “because you know, there’s certainly a lot of discussion about climate change deniers being appointed to, say, key environmental positions. It’s strange to me because we have so much documentation to show that climate change is real, 97 percent of scientists believe it, but then we have other people claiming it’s not. I think that it is just a really dangerous place that we’re in because the way that we’ve established how we document things, how we gather information, how we find sources we trust, I feel like it’s all up in the air right now.”

“It does feel in flux,” I say. “I feel like, also, there’s kind of an undeniability to paper.”

“I know, I know,” says Coyner. “It’s so interesting. People are conditioned, if there’s not a piece of paper to document something, then it didn’t happen.”

And yet, we’re moving away from paper. Could this, in some small way, be contributing to our cultural insecurity?

“I had a professor in graduate school,” says Coyner, “and she said we’re as close to a paperless office as we are to a paperless bathroom.”

In other words, don’t hold your breath.

“But moving forward,” she adds, “the preservation of electronic records [or, born digital records] is very interesting. I think that there’s going to be gaps because permanence doesn’t function the same way in the digital realm. It’s probably the biggest thing facing our profession right now.”

Hollywood doesn’t seem to have figured this one out either. In the latest Star Wars film, Rogue One, digital archiving is central to the film’s plot. In a recent blog post, “How Not to Build a Digital Archive: Lessons from the Dark Side of the Force” the minds behind the digital archiving company Preservica point out, “all is not perfect with the Empire’s choice of archiving technology.”

For example, “No metadata to prove the provenance of the plans — how could you be sure you were looking at the right Death Star plans?” This is just one of several flaws listed. The climactic battle of Rogue One takes place over a library, over retrieving a cartridge in an archive containing the plans for the Death Star.

In Arizona’s collaboration with Ancestry.com, other records that residents will now have access to include school census records, marriage records, wills and probate records, and territorial and early state prison records.

“This partnership allows historians, demographers, sociologists, students of Arizona history, and genealogists access to over 3 million names in 10 separate record collections,” says deputy state archivist Dennis Preisler. The records can be accessed here.

Hearing from information workers about an emphasis on collaboration, easier access, and a greater connection to the communities they serve gives me hope for the future; that, along with the promise libraries have always made that people, regardless of their circumstances or backgrounds, could have access to information and a safe space for learning.

So, back to my co-worker and our idea for a television show about librarians. Would The Library make great television? Debatable. (Though according to the Phoenix Public Library’s 2015 annual report, 4.2 million customers visited a Phoenix Public Library branch that year, and library services were accessed a whopping 33.5 million times through the library’s website. Not bad potential viewership.)

But can libraries and archives be used as a social change tool? I think so. Maybe, they just remind us of who we are. If we are what we archive, here is a look at some defining material.

Read on for some of the amazing materials found in Arizona's libraries and archives.

This photo of Arizona farm workers in the 1970s is part of the Chicano/a Research Collection at ASU.

ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

Watch the motion picture of John F. Kennedy speaking at the Westward Ho in November 1961. The event was the 50th anniversary of Senator Carl Hayden’s service in Congress, and Kennedy speaks for eight minutes — eight minutes of heretofore unseen, or long unseen, video of President Kennedy. The footage was digitized from 2” video, which is extremely rare. There are only a few machines left that can play it, so archivist Rob Spindler sent it to a firm in Kentucky that was able to do the transfer. “Someone has to sit there in front of the machine and adjust the tracking as they go,” explains Spindler. “So this is actually a work of artistry to be able to recover something like this.”

According to Spindler, “The thing that is, in my mind, the most amazing about it really is Carl Hayden’s speech. He talks about being elected to Congress in 1912. The first election when Arizona was a state.” Hayden talks about meeting William Jennings Bryan on the train to Washington, D.C. William Jennings Bryan was a candidate for the presidency three times in 1896, 1900, and 1908. “But just the idea that this guy speaking in 1961, remembered 1912 and William Jennings Bryan, is just amazing,” says Spindler. “So you get this sort of interesting overlap. A thing created in 1961 tells you about 1912, and we just digitized it in 2016.”

The Place: Arizona Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: materials covering prehistoric Arizona to the present containing manuscripts, oral histories, personal papers, and photographs

How You Can Access It: ASU’s Digital Repository

Take part in a Latino Genealogy and Preservation Workshop

Participate in a workshop to preserve family archives through the Chicano/a Research Collection. Archivists throughout the state took part in a statewide survey of collection holdings in 2011 and 2012, called the Arizona Archives Matrix. They wanted to see what was being collected across repositories and what areas were under-documented subject areas. The survey showed that ethnic minority groups have been marginalized in collection holdings, specifically African-Americans, Latinos, and the Asian-American community, as well as other minorities like the LGBT community and even certain religious groups. Seeing that there was under-documentation, curator and librarian Nancy Liliana Godoy-Powell developed a workshop that offers participants options for how they can preserve their family history. At the workshop she gives out archive kits that include an archival box, protective plastic sheets, and acid free folders.

“Everything’s bilingual because we want to reach everyone in the Latino community,” says Godoy-Powell. The next workshop will take place at the Burton Barr Central Library, February 28, 6 to 7:30 p.m.

The Place: Chicano/a Research Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: the largest Mexican-American archival collection in the state of Arizona

How You Can Access It: Luhrs Reading Room, Hayden Library, Level 4, Monday-Friday 9 a.m.-6 p.m., 480-965-2594, libguides.asu.edu/chicanocollection

See the Midcentury Modern architectural renderings of Jane Karl

The State Archives took responsibility for some architectural collections in 2014 after local architects pointed out that not only were many Midcentury Modern architects aging, but these records were falling through the cracks.

“So we’ve started collaborating with Modern Phoenix and [its organizer] Alison King, who’s really helped coordinate a lot of transfers,” says archivist Libby Coyner. See the visually stunning architectural drawings and renderings of Jane Karl who was on contract to John Long, Del Webb, and a number of other developers and architects in the Valley.

The Place: Arizona State Library, Archives & Public Records

Location: Arizona Memory Project

What They Collect: oral histories, photographs, maps, government documents, and multimedia from the State Archives as well as many other Arizona repositories.

How You Can Access It: azmemory.azlibrary.gov/cdm/landingpage/collection/archkarl

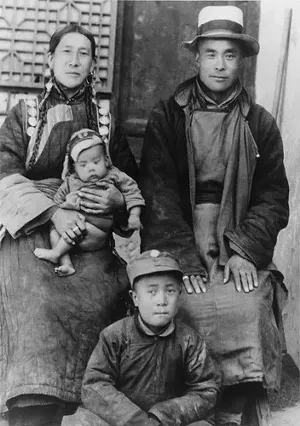

See the Dalai Lama’s family pictures

Want to see the Dalai Lama’s family pictures? These were taken by a man named A.T. Steele, an American journalist who travelled to Tibet twice, in 1939 and again in 1944.

The Place: Special Collections

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: rare books and manuscripts plus special-interest collections

How You Can Access It: ASU’s Digital Repository

Look at the history of farm workers in Arizona

The Gustavo Gutierrez Papers and Maricopa County Organizing Project (MCOP) Records preserve the statewide efforts to organize and unionize undocumented Mexicans and Mexican-American farm workers in Arizona. At first, the United Farmworkers Union wasn’t friendly with undocumented people, because undocumented workers were often breaking strike lines, which produced tension on both sides. In Arizona, it was Gustavo Gutierrez, a Chandler native, who helped unify, and unionize, both the undocumented community and the Mexican American community.

Arizona farm workers established the Maricopa County Organizing Project in 1977. MCOP organized the Goldmar Strike, one of the largest undocumented worker strikes in Arizona history. The collection houses records documenting strike strategies and union positions on working conditions and health care, among other topics. To see an online finding aid, visit the Arizona Archives Online.

The Place: Chicano/a Research Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: the largest Mexican-American archival collection in the state of Arizona

How You Can Access It: asulibraries.omeka.net/exhibits/show/crossing-the-border

Learn about the guy who designed the old Valley National Bank branch at 44th Street and Camelback Road

Visit the Valley National Bank branch at 44th Street and Camelback Road (now a Chase branch). The building is the design genius of Frank Henry; there’s even a little honor wall inside the bank for him. Henry was the first person to receive a professional degree in architecture in Arizona, when he graduated from ASU in 1960. He had a deep appreciation for the ecology of the Southwest and, though more of a draftsman, he did some really amazing things, more of which can be discovered in the Frank Henry Papers housed at ASU.

The Place: Arizona Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: materials covering prehistoric Arizona to the present containing manuscripts, oral histories, personal papers, and photographs

How You Can Access It: Luhrs Reading Room, Hayden Library, Level 4, Monday-Friday 9 a.m.-6 p.m., 480-965-4932, or the Arizona Archives Online

Consider old prison registers

Most of the State Archives collections are related to government, including old prison registers.

“If you look at them, they contain photographs; they have a whole section on tattoos. And I think it’s really interesting to think about tattoos as an identification method,” says Coyner. She adds that it’s also interesting to see these records in light of the Black Lives Matter movement and concerns around police brutality and profiling. You can see some of these issues reflected in a lot of prison registers.

Adds Coyner, “We have the older stuff, so it is in big bound volumes. I’ll be curious because I think most institutions have gone to electronic databases, and we currently don’t have the resources to have a trusted digital repository so a lot of times we can’t accept those kinds of records because we can’t guarantee that we can maintain them.”

The Place: Arizona State Library, Archives & Public Records

Location: Polly Rosenbaum Archives and History Building

What They Collect: legislators’ papers, state and local government records, private manuscript collections, and maps

How You Can Access It: 1901 West Madison Street, Monday-Friday 8 a.m.-5 p.m., 602-926-3720, www.azlibrary.gov/arm/research-archives

Martin Luther King Jr. (second from right) visits Tempe in 1964.

ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

Hear audio of Martin Luther King Jr. from 1964

When I ask about audio of Martin Luther King Jr. speaking in Tempe in 1964, Rob Spindler says, “Now there’s a great story.” The University Archives had a photograph with ASU President G. Homer Durham, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, the Monsignor Robert Donohoe, and two others.

“So, we’ve had this photo for years and we put it online. And one day I get a call. This lady says, ‘I see you have this great photo of Martin Luther King at Arizona State University. Do you have a transcript of what he said?’ This was in the spring of 2013, and I said ‘No, I wish we did.’”

The woman said, “Well, I may have something for you.” A couple of days later she came to Spindler’s office with a rollaway suitcase filled with reel-to-reel audio tapes. One of them said, right on the label, Martin Luther King, Tempe, Arizona, 1964. She’d purchased the material in a local Goodwill for $3 a tape. It was a remarkable find. She signed the material over to ASU and the tapes were digitized. It was a perfect full-length recording of King’s entire speech.

It is June 1964, and King talks about the filibuster in Congress of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; he also exhorts the crowd to fight for equal accommodations in Arizona, which was still a Jim Crow state in 1964. It wasn’t until the fall of that year, after King’s visit, that Arizona passed its first public accommodations bill that got rid of separate white and colored facilities. For more MLK archival materials at ASU, including a transcript of the speech and photographs, see https://repository.asu.edu/collections/164

The Place: Arizona Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: materials covering prehistoric Arizona to the present containing manuscripts, oral histories, personal papers, and photographs

How You Can Access It: ASU’s Digital Repository

Visit the Rare Book Room

While in the Rare Book Room, browse the glass bookcases for a first edition of your favorite novel. War of the Worlds, perhaps? Or ask the Rare Book librarian, Heather Kendall, if you can make an appointment to see the clay tablets. I saw one from Southern Iraq that dated to about 1970 BCE, making it almost 4,000 years old. It was recently translated by someone who studies cuneiform, and, as it turns out, is a receipt. Not, as I had hoped, the answer to the universe. A tour is scheduled for 2 p.m. on Saturday, March 25. Registration required: www.phoenixpubliclibrary.org/Locations/BurtonBarr/Pages/Rare-Book-Room.aspx

The Place: Rare Book Room

Location: Phoenix Public Library, Burton Barr Central Library, Fourth Floor

What They Collect: the Alfred Knight Collection of rare, historically significant books and an Artist Made Book Collection

How You Can Access It: 1221 North Central Avenue, 602-262-4636, or e-mail [email protected]

Barry Goldwater speaks at the Camelback Inn in 1964.

ASU Libraries, Archives, and Special Collections

Because media was so important in Goldwater’s presidential campaign, there’s a lot of film, video, and radio broadcasting material, all part of the 970 boxes that make up the personal and political papers of Senator Barry M. Goldwater.

The collection contains boxes of legislative materials, personal correspondence, campaign files, and audio-visual materials. A Finding Aid for all of the materials can be viewed here: azarchivesonline.org/xtf/view?docId=ead/asu/goldwater.xml

The Place: Arizona Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives, and Special Collections

What They Collect: materials covering prehistoric Arizona to the present containing manuscripts, oral histories, personal papers, and photographs

How You Can Access It: ASU’s Digital Repository

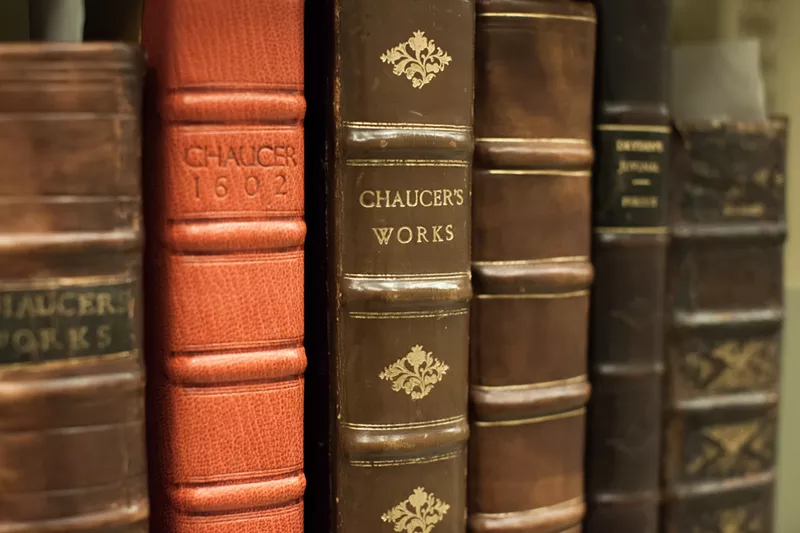

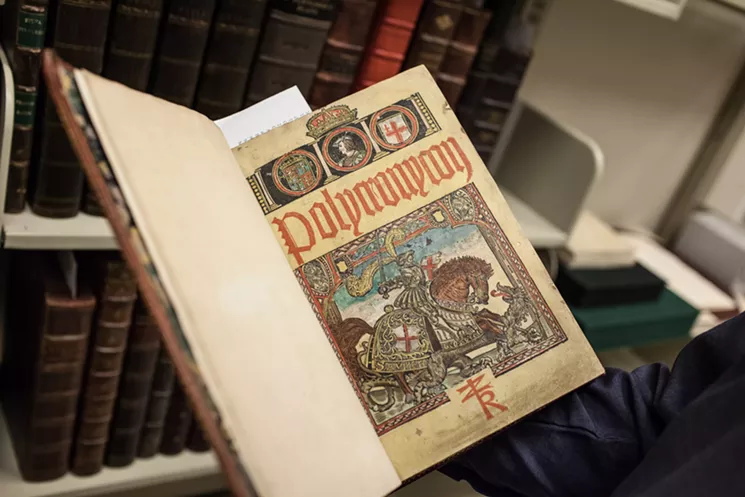

The Polycronicon, a 1527 book about the history of England.

ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

See the rare book Polycronicon from 1527

The Lawler Library of rare, early printed books is part of the Special Collections repository at ASU. The collection is small but mighty, including the Polycronicon from 1527, considered the most important text related to the history of England in the 16th century. It’s also the first English book printed in which musical notation occurs. There are only a handful of these that have survived in this condition. Also part of the library are works by Geoffrey Chaucer, John Milton, William Shakespeare, and Francis Bacon.

The Place: Special Collections, The Lawler Library

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: rare books and manuscripts plus special-interest collections

How You Can Access It: Luhrs Reading Room, Hayden Library, Level 4, Monday-Friday 9 a.m.-6 p.m., 480-965-4932, e-mail: [email protected]

A photo of a female impersonator at Charlie’s Bar in 1987, from the BJ “Bud” Memorial Archives documenting LGBT history.

ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

Learn about LGBT history in Arizona through the BJ ‘“Bud” Memorial Archives from the Stonewall riots in 1969 to 2014. The collection represents 45 years of LGBT history, including photographs, artifacts, organization records, and correspondence documenting the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) experience in Arizona including AIDS, hate crimes, and pride festivals. The project began in 2015, and 151 boxes of material have been processed for the collection.

The Place: Arizona Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: materials covering prehistoric Arizona to the present containing manuscripts, oral histories, personal papers, and photographs

How You Can Access It: asulibraries.omeka.net/exhibits/show/lgbt-history-in-arizona

See the McCulloch Brothers Inc. Photographs, 1884-1947

Last year, ASU released more than 4,500 digital images from the McCulloch Brothers Collection showing early Phoenix city scenes, streets, architectural views, and more. Click and download high-resolution publication-quality images.

The Place: Arizona Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: materials covering prehistoric Arizona to the present containing manuscripts, oral histories, personal papers, and photographs

How You Can Access It: ASU’s Digital Repository

Learn about the Chicano art movement

Two collections, Xico, Inc. Records and Movimiento Artistico Del Rio Salado (MARS) Records, preserve the history of Chicano/a artistic expression in Arizona. The collections house correspondence, membership records, slides, photographs, grant records, and more.

The Place: Chicano/a Research Collection

Location: ASU Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

What They Collect: the largest Mexican-American archival collection in the state of Arizona

How You Can Access It: Luhrs Reading Room, Hayden Library, Level 4, Monday-Friday 9 a.m.-6 p.m., 480-965-2594, libguides.asu.edu/chicanocollection

Use a printing press from 1895

Every year, as part of the Summer Solstice Celebration at the Burton Barr Central Library, the Rare Book Room holds an open house where visitors are allowed to work the Ostrander Seymour Co. printing machine, including rolling the ink and pulling the hand press. Participants get to keep their print, which is typically a poem and woodcut designed by library staff. The event is called Press-a-Verse; look for it in the library’s calendar of events.

The Place: Rare Book Room

Location: Phoenix Public Library, Burton Barr Central Library, Fourth Floor

What They Collect: the Alfred Knight Collection of rare, historically significant books, and an Artist Made Book Collection

How You Can Access It: 1221 North Central Avenue, 602-262-4636, or e-mail [email protected]

See original music by Arizona composers from the 1930s

Look at two volumes containing original music by Arizona composers from the 1930s. In the 1910s and 1920s in the Southwestern region, women’s organizations were key in forming the nucleus for things that would later become art museums, symphony orchestras, literary societies, and other cultural institutions.

The Arizona Room at the Phoenix Public Library has a two-volume work containing original music by Arizona composers ranging from a 10-year old girl to professionally trained musicians that was compiled by one of these women’s organizations in the 1930s. Each piece of music, some of it written by hand, some of it professionally printed, is accompanied by a biographical statement of the composer. It even has a handwritten full orchestral piece written in pencil. The range of music in the volumes includes choral songs, etudes, foxtrots, social music, dance music, violin instruction, religious music, music that was written to dedicate a building, and a Hawaiian slack key guitar how-to-manual.

The Place: Arizona Room

Location: Phoenix Public Library, Burton Barr Central Library, Second Floor

What They Collect: heritage, lifestyle, and geography of the desert Southwest from prehistoric times to the present

How You Can Access It: 1221 North Central Avenue, Monday, Friday, Saturday 9 a.m.-5 p.m., Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday 9 a.m.- 9 p.m., Sunday 1-5 p.m., www.phoenixpubliclibrary.org

Listen to oral histories from the Phoenix civil rights movement

There are four Arizona Historical Society locations: Flagstaff, Tempe, Tucson, and Yuma. Each location has a specific geographic and subject focus. The Tempe AHS branch has oral history records from the Phoenix civil rights movement. The interviews were conducted by Mary Melcher and cover segregation, social life, and customs in Phoenix.

The Place: Arizona Historical Society Archives

Location: AZ Heritage Center at Papago Park

What They Collect: chronicles the economic, political, social, and cultural heritage of the state by collecting published and unpublished material of historical and research value, including manuscripts, diaries, photographs, letters, maps, oral histories, books, and more

How You Can Access It: 1300 North College Ave., Tempe, 480-387-5355, Monday-Thursday 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Friday and Saturday 10 a.m.-4 p.m., catalog.azhsarchives.org

Browse the old clipping files

“Something that is unique to our collection is our clipping files, which cover mid-1960s to the early 1990s,” says librarian Jean Barry. “Library staff were literally going through each newspaper, clipping articles, and then putting them into topical files. And, as far as we know, it’s unique to the area. It’s really the only index for The Arizona Republic for that time period.” The Arizona Republic has an online database, but that only goes back to 1999. Use the clipping files on-site. Copying of most materials is available at 20 cents per page.

The Place: Arizona Room

Location: Phoenix Public Library, Burton Barr Central Library, 2nd Floor

What They Collect: heritage, lifestyle, and geography of the desert Southwest from prehistoric times to the present

How You Can Access It: 1221 North Central Avenue, Monday, Friday, Saturday 9 a.m.-5 p.m., Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday 9 a.m.-9 p.m., Sunday 1-5 p.m., www.phoenixpubliclibrary.org

Read newsletters from Japanese internment camps in Arizona

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order that provided for the creation of the war relocation authority, and 10 different relocation centers were created for people of Japanese lineage. Two of those were here in Arizona; there was the Posten camp on the Colorado River and the Gila River Center. Each of those camps had its own newsletter that was written entirely by the individuals who lived there. The Arizona Room at the Phoenix Public Library has those newsletters available on microfiche. The newsletters encapsulate what life was like, with residents trying to create a sense of normalcy in difficult circumstances.

The Place: Arizona Room

Location: Phoenix Public Library, Burton Barr Central Library, Second Floor

What They Collect: heritage, lifestyle, and geography of the desert Southwest from prehistoric times to the present

How You Can Access It: 1221 North Central Avenue, Monday, Friday, Saturday 9 a.m.-5 p.m., Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday 9 a.m.-9 p.m., Sunday 1-5 p.m., www.phoenixpubliclibrary.org

Other Collections to Explore

The Place: Phoenix Art Museum

Location: Lemon Art Research Library

What They Collect: PAM Library’s collections include materials on art criticism and art history, with emphasis in Asian, Latin American, Western American, European, modern, contemporary, and fashion design. The library also maintains artist files, including files on local artists. It is a noncirculating research library.

How You Can Access It: 1625 North Central Avenue, 602-257-2136, Tuesday-Friday 10 a.m.-4 p.m. and the first Wednesday of every month from 10 a.m.-7 p.m., www.phxart.org/visit/library

The Place: The Heard Museum

Location: Billie Jane Baguley Library and Archives

What They Collect: materials that document American Indian history, culture, and art. The collection is particularly strong in the North American Southwest, and a centerpiece of the archival holdings is the Native American Artists Archives with original and special material documenting artists’ careers.

How You Can Access It: Second Floor, Upper Level North, Marguerite S. Roll Research Wing, 2301 North Central Avenue, 602-251-0281, Monday-Friday 10 a.m.-4:45 p.m. Appointments encouraged; visit heard.org/library/archives

The Place: Cline Library, Special Collections and Archives

Location: Northern Arizona University

What They Collect: the history and culture of the Colorado Plateau and Northern Arizona.

How You Can Access It: library.nau.edu/speccoll/resources/exhibits.html

The Place: Special Collections at the University of Arizona Libraries

Location: University of Arizona

What They Collect: primary research materials chiefly in the fields of literature, Arizona and Southwestern history, and the sciences. Also has substantial collections relating to the lands and peoples of Arizona, New Mexico, and Sonora, Mexico

How You Can Access It: speccoll.library.arizona.edu/collections