Nate Valdez is good with fingers. Take, for example, his care when removing jewelry from them. First he coats a finger with wax. Then he ties a string around its base and wiggles it up slowly behind the ring it's wearing until the ring slinks off the tip at the fingernail. He calls this "the string technique," and it is the best way to get these things off a corpse without ripping the skin off with them. Despite his caution, there will still be little flakes of flesh on the table, from where the dermis layer has separated from the subcutaneous tissue because the body has been dehydrated by its owner's passing.

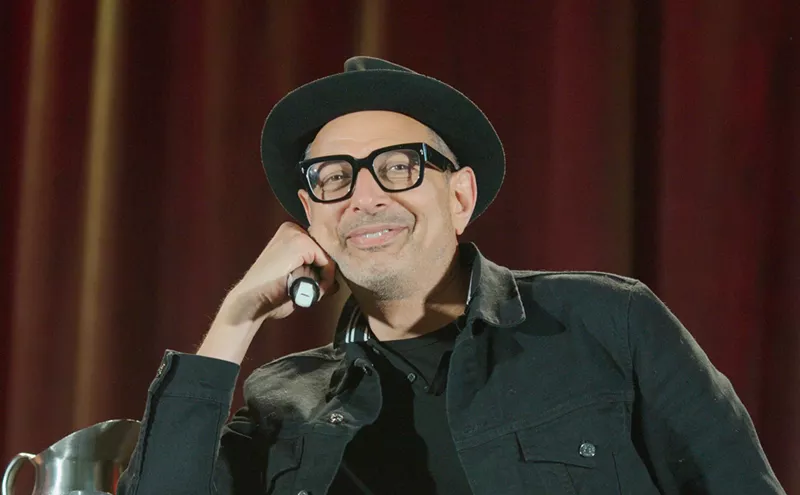

Nate is not your typical undertaker. He's 27 years old, still in the prime of his life, and yet he spends each day working at a mortuary, confronting a reality that most of us spend our whole lives avoiding: the inevitability of death.

Nate's fingers are more widely recognized as the vehicles for the driving guitar lines of his band, In the Whale, which in 2014 celebrated the release of its third EP. He has spent time living in a van on the road in the service of his music. But when he moved from Greeley to Denver with bandmate Eric Riley, he decided to seek steady work during the day, which led him to the mortuary. Nate says music has always been how he gets through his days; now his days are just a little harder.

He thinks the mortuary probably hired him because he's still strong enough to lift all the dead people onto the embalming table and manhandle them into their viewing outfits. He doesn't mind dressing the bodies or, say, curling their hair. But he doesn't like to do their makeup (he says they all end up looking like Mimi from The Drew Carey Show), and he really doesn't like cutting the sacred clothes of the deceased in order to squeeze their rigid limbs into their favorite pair of jeans. A few years ago, he had to dress a seven-year-old who had been hit by a drunk driver. Some days are harder than others.

It's Nate's job to make bodies feel like people, but he doesn't romanticize his work. His stories are filled with peristalsis, Y incisions, sphincter muscles and capillaries. They possess the clinical accuracy you'd expect from someone who has grown familiar with the human form from days of sewing together torsos and reconstructing limbs. He has to disconnect from the people who come in every day; he can't think about the fact that the mouth he is screwing shut was probably kissed just days before by someone who loved those now-purple lips. The tricky relationship between bodies and their inhabitants is one he's been thinking about for most of his life.

Before Nate was born, his grandpa owned a mortuary in small-town Pennsylvania. There he was the coroner, embalmer, ambulance driver and funeral director. He was a morbid one-man band until he moved his business to Las Animas, Colorado, where, with a population of 2,302, there was enough death to make more than one man's living. He enlisted a young Nate to help.

Nate was fourteen when he saw his first dead body. "I remember how sterile it was," he says. His eyes and nose burned from the body packs — chemical-soaked wads of cotton stuffed in the body's orifices for the embalming process. He was in many ways unprepared for this intimate exposure to Mr. Jones, the owner of the tackle shop down the street.

"It's kind of a weird feeling to be in a room with someone who's dead," Nate says. "It's not something normal."

Still, he was captivated by the way the world had just stopped for Mr. Jones, and by how his body still looked like that of the Mr. Jones he'd known in life. He wanted to know what his grandfather had done to make the man look so alive, even in his unbreakable stillness. Thirteen years later, this still fascinates him.

The coffee table in his Denver living room is a coffin. It's a recent addition; it joins the embalming table in the dining room. And he's still got his grandpa's old mortuary van in the driveway. And yet these strange tokens from Nate's day job are overwhelmed in the apartment by the stacks of In the Whale merchandise, the framed edition of Music Buzz with his face on the cover, and the instruments scattered around the room. There's a ukulele hanging on the wall, which he strums idly as he talks. On the day we talked to him, he had a harmonica stashed in his shirt pocket.

The van is now a tour bus. He stripped it of its original equipment in order to make room for amps, guitars and drum sets. He's gotten good at only hanging on to the useful parts of the things in his life. You can't carry your work with you all the time when you have a job like his.

Still, the work has affected him. Nate has stopped watching horror films. On a normal day, he might see a guy with the back of his head blown off. His daily life is a horror film, he says, and he just doesn't feel the need to watch some director replay it for him when he gets home. He finds little entertainment in death.

A few months ago, Nate went in to work and saw a familiar face on the embalming table: It was the man who'd hired him at the mortuary. They had talked every day — about their shared history in Greeley, about the new medication the man was trying for his arthritis. Nate had shared his childhood memories of driving with his mom to play at the nearest open-mic night, fifty miles away. Then one day his old boss showed up with a tag on his ankle and his mouth screwed shut forever. It's one of the only times Nate has cried on the job. "It's difficult," he says, "because people do love each other."

Two years ago, Nate met his girlfriend, Seneca Garrison, at a hipster church where it's okay for you to be a little drunk and a little bitchy. She gradually saw the mortician in him emerge in their relationship.

Instead of kissing her cheek or squeezing her hand at night after work, for example, Nate playfully presses his fingers into her left shoulder. It's the exact motion he uses to search a corpse for a pacemaker, which will explode in the crematorium. It's a self-aware, if morbid, gesture, and when he does it, Seneca just rolls her eyes and smiles.

She quickly noticed that death is table talk in Nate's family. Shortly after they began dating, Seneca found herself in a hot tub with her new boyfriend, his mom and a handful of strangers. They were talking about the death of the neighbors.

"Do you remember Mrs. Jenkins, who gave you piano lessons?" his mother said. "Do you remember her husband? Well, guess what? He killed himself."

Like his mom, Nate ticks off the names of the dead people he's known the way most people read through a grocery list, interrupting the inventory now and then to supplement a name with a poignant memory or a physical marker. His work has taught him to respect life and its finite nature, but he's matter-of-fact about death. He has no problem singing lines like, "I want to take you to a lake of fire, you and me and Rosemary's Baby."

Nate views his job as merely a role he has to play in society. "I know what I do is a necessity," he says, tapping his fingers absentmindedly on his coffin table. "Much like a vulture is built to clean up all the dead riff-raff or a sucker fish to clean up a tank. I'm doing my part."

The mortuary has offered to pay for him to take a course to become a certified embalmer, though Colorado is the only state where you don't actually need one to legally embalm. The staff of mostly fifty-somethings like Nate, and they want him to stay. If he wants a future in the death business, a multimillion-dollar industry, he can have one. "We'll see," he replies with a shrug when asked if he'll make his day job a long-term career. He doesn't look up from his phone. His band's manager has just texted him a list of questions about In the Whale's next show.

Next month, the band is going on tour. One of the stops is in Kansas City, where Nate plans to wait three hours in line to get the famous barbecue at Oklahoma Joe's. He's young, and he has plenty of time to do that kind of thing. Eventually, though, he will die, and when he does, he wants to be cremated. That way, nobody will have to squeeze him into his favorite jeans.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "21251496",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "21327862",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "21934225",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17012245",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]