“Ten minutes after I went out, her husband called me and said 'She coded. She’s dead,'” Ryan said.

The previous night, Ryan's daughter Pamela Cooper, 49, had worked a shift of more than 15 hours at Phoenix's 911 dispatch center. Cooper was a 20-year veteran of the dispatch center, but it was her first week back after six weeks recovering from COVID-19. She was still feeling unwell but was out of paid leave and supporting both her mother, a widow on social security, and her husband, whose unemployment has run out.

“She said, 'I got to work to pay the bills,'" Ryan remembers.

The first few days were difficult, but on Friday, February 26, Cooper really started to go downhill.

"I can't breathe at all right now...ugh," Cooper texted her mother around 3:30 p.m. on Friday during her lunch break.

Cooper was supposed to leave work at 7:30 p.m., a standard 10-hour shift, but she was ordered to stay on until nearly 1 a.m.

"If they mandate overtime today you'll be going home in an ambulance," Ryan wrote to her.

"Yep. I've mentioned that," Cooper replied. A few messages later: "No opting out or I get written up."

This winter, when COVID-19 swept through Phoenix's police dispatch, which handles all the city's incoming 911 calls, the center was already understaffed due to relatively low pay and burnout. Currently, 51 of the 299 positions between the police and fire departments, which operate separate dispatches, are unfilled. City officials were looking at bumping pay last year but put it off due to budgetary uncertainty caused by the pandemic.

A union official estimates that around one in five of the approximately 187 police dispatchers contracted the virus in December and January alone, including Cooper.

To deal with the resulting staff shortages, management has used mandatory overtime and "hold over" shifts, where dispatchers stay past the end of their 10-hour workday. Even now that COVID-19 has subsided, mandatory overtime has remained in place to deal with staffing shortages caused by missed shifts and burnout-driven resignations driven in part by those same measures.

###

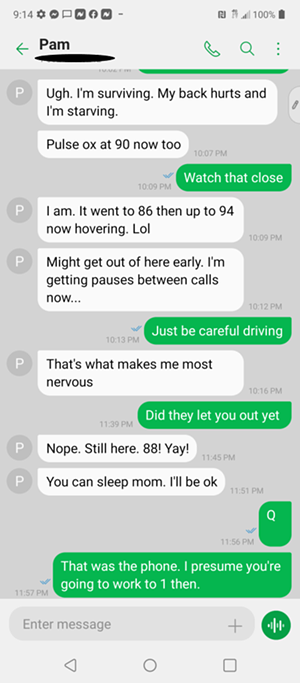

"They are telling me I have to stay until 1 now... I'm sitting here crying. If I get worse, I'm MAKING them call me an ambo (ambulance)," Cooper wrote at 4:50 p.m.

A little after 10 p.m., Cooper texted her mother to say that her pulse oxygen level was fluctuating between 86 and 94. Anything below 90 is considered low, according to the Mayo Clinic. Ninety minutes later it was back down to 88.

Cooper eventually left work at 12:45 a.m., exhausted. The next morning, she collapsed at home. Her lungs had stopped working. Medics were able to revive Cooper, but her heart stopped once before she made it to the hospital and twice after she arrived. She never regained consciousness. Her brain is swollen from the lack of oxygen. She's on life support but doctors don't expect her to survive.

“They truthfully say it would take a miracle," Ryan said from next to her daughter's intensive-care bed at Banner Baywood Medical Center. "But miracles do happen.”

Ryan blames the city for not doing more to protect her daughter from COVID-19 and for forcing her to stay on when she was unwell.

“I think they just plain flat wore her out," said Ryan, her voice catching. She also faults the city for not beginning deep cleanings until after Cooper had already contracted the virus in January.

City spokesperson Vielka Atherton declined to comment on Cooper's situation specifically, citing medical privacy. She referred to answers she had provided from city officials last week regarding concerns about COVID-19 in police dispatch and understaffing.

In that response to a series of detailed questions from Phoenix New Times, city spokespeople said that they'd put extensive measures in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in dispatch, including separating out dispatchers between two call centers, alternating work stations, adding plexiglass barriers, and offering free COVID-19 testing.

"Unfortunately, not all transmission can be prevented," the city said. "It’s also important to note that the role of a dispatcher is not one that can be filled quickly. Dispatchers must complete a rigorous training program before they can begin serving the public. These requirements are not altered or eliminated because of the pandemic and or staffing needs."

City officials said that dispatchers were given clear instructions as well as all material needed to keep their shared workstations clean.

"In addition to the City Safety guidance on employees cleaning their work stations regularly, the city provided augmented cleaning by contracted staff, including the cleaning of work station touch points twice daily at both dispatch locations," they wrote.

Not everyone agrees that the city did enough. New Times spoke to three dispatchers who said that more could have been done. All spoke in their capacity as union representatives with AFSCME Local 2960 due to restrictions on police department employees talking to the press.

Dorie Levy, a 20-year dispatch veteran, said she was out for surgery when the cases started breaking out. She said she worked the phones from her hospital bed as the union tried to push for expanded cleaning and supplies.

Levy and dispatcher Wilechia Burns both said that for a time dispatchers were told they could only use one Clorox wipe per shift to sanitize their workstations. In the city's response to New Times provided by Atherton, officials denied that this was ever a policy and said that workers were given materials to wipe down their station before and after shifts, on top of contracted cleaning.

According to the women, supervisors didn't always take COVID-19 seriously. In late October, some supervisors decided to resume holding in-person, indoor shift briefings for several weeks. In another case, Levy said, a coworker received her positive COVID-19 test results during a shift, and a supervisor had her stay to fill out a leave form before going home. The city says the in-person briefings were due to a miscommunication and that supervisors are told to send dispatchers home immediately if they are sick.

It wasn't just supervisors. The dispatchers said that some of their coworkers didn't take things seriously either, gathering in groups to talk and rolling plexiglass screens out of the way. During the COVID-19 surge over the holidays, at least 20 attended a holiday gathering together, Levy said.

Some challenges were unavoidable. The spike in cases corresponded with the accelerated spread of the virus in the community this winter. The two dispatch centers are enclosed spaces where dispatchers say that it's not possible to wear a mask while handling calls — even relatively thin surgical masks make them difficult to understand through their headsets. And calls come in from special 911 phone lines, so working from home isn't an option.

"There's no windows to open in a dispatch center," said Frank Piccioli, the union head and a current dispatcher.

By the end of December, 12 dispatchers had contracted COVID-19. In January alone, more than 20 did. Levy said one ended up hospitalized and several were treated for pneumonia.

This was around the time she returned to work from an unrelated surgery.

“I was extremely scared," she said. "I wore my mask as much as I could.”

Marie Katzenberger, another dispatcher, wasn't as concerned. She said that there's usually a spike in absences during winter due to sickness. She said dispatchers were told to stay home if they felt unwell at all, which could have meant people called in sick without needing to, or took advantage of that policy to actually take care of family members.

City spokespeople said they could not provide data on how many dispatchers contracted COVID-19 as they only track cases at the department level in order to protect the privacy of employees, but as of last Wednesday, 539 sworn officers and 232 civilian police department employees had contracted the virus. That means 190 sworn officers and 102 civilian employees tested positive for COVID-19 in the two months since late December.

###

The spread of cases had an impact beyond dispatch, as well. A community group member told the city council's public safety and justice committee in January that block watch members were being discouraged from reporting suspicious activity due to the delays they were experiencing.

"When you're routinely on hold for (non-emergency reporting line) Crime Stop for 10 minutes or more — I've experienced hold times of more than 30 minutes — this is very, very frustrating to people that are trying to be engaged in neighborhood advocacy and block watch," said Jeff Spellman, a Violence Impact Coalition organizer.

Levy confirmed that she saw non-emergency calls hold for more than 30 minutes at times due to the resulting staffing shortages.

“And that can have life-threatening ramifications on our callers,” she said. She said some callers aren't aware they're actually in an emergency situation until they're able to speak with a dispatcher, which is why they try to keep hold times minimal.

There are no national standards for non-emergency calls, but 90 percent of 911 emergency calls are supposed to be answered within 15 seconds, and 95 percent within 20 seconds. The city only provided New Times with summary data for 2020, but even that shows the city fell short: only 85 percent of calls were answered in 15 seconds and only 89 percent were answered within 20 seconds.

Dispatcher Wilechia Burns said she saw emergency 911 calls hold for as long as two minutes during the staffing crunch this winter.

“With less people on the phones, those calls will hold," said Burns, who's been with the department for a total of eight years. "That’s something I don’t think any of us feel is acceptable. But we’re doing what we can.”

The number of cases has subsided in the last month and dispatchers have started receiving vaccinations, which should help protect against further outbreaks, but they are still feeling the strain of understaffing. Levy said she has talked to dispatchers who have called in sick because they were burnt out and don't feel up to navigating high-stakes situations.

"If they don't feel 100 percent that day, that could cost an officer his life," she said.

Those absences, exacerbated by a number of resignations, have meant that the mandatory overtime has stayed in place. Dispatchers are expected to work eight hours of overtime each week, as well as two on-call shifts. This left them only one day a week truly off, all while handling stressful and traumatic work material.

The city has long known that staffing was an issue, but has fallen short of addressing the underlying pay issues.

Phoenix human resources head Lori Bays told a city council committee in January that while dispatchers in other Valley cities handle an average of 20 calls a day, a busy day in Phoenix can see 200 calls — many of them more serious than other cities have to deal with. Despite this, average salaries for the Phoenix 911 workers are not much higher than in other Valley cities and are $10,000 lower than in Tempe, which has the region's highest average salary.

"If you can work for Phoenix, for example, and have to manage up to 200 calls per day, or you can work for another city and have an average of 20 calls per day and make approximately the same amount of money, some of our dispatchers have chosen to do that, and I think all of us can see why that might be the case," Bays said.

Beyond pay, the traumatic nature of the dispatchers' work contributes to high burnout rates. Last May, a workgroup submitted a report to the city manager advising ways to address the situation. The workgroup, made up of city administrators and dispatchers, recommended actually overstaffing dispatch to account for the expected burnout, along with a series of other measures to improve working conditions.

After hearing about the report at the January meeting, Councilmember Thelda Williams voiced her impatience, saying she was "very concerned."

"You just say well you're working on it, you're working on it, you're trying to do it, but I want to know when you expect to have real results?" she said, pressing Bays.

Since the report was submitted in May, the city has instituted a number of its recommendations, such as streamlining hiring, Bays said. But the central issue — increasing salaries — would require the council to approve additional funding, and the decision was made to put it off for another year due to uncertainty about the financial impact pandemic.

In response to New Times' inquiries, the city said that once they can fill the open jobs they'll be able to assess the need for additional staffing.

"Now that our budget is more stable, we are actively studying 911 dispatcher pay and expect to be making recommendations to City Council within the next few months," wrote city spokespeople.

###

Any changes will come too late as far as Cooper's mother, Ryan, is concerned. She wants someone held accountable for her daughter's life.

“I don't know if I’m more grief-stricken or angry,” she said.

She believes that more cleanings would have made a difference and she's sure her daughter was infected at work.

"She barely did anything else," she said.

Ryan said that as well as struggling with asthma, Cooper was born with a birth defect on her hand that required dozens of surgeries and hundreds of resulting stitches. Despite her own struggles, she spent 20 years helping others as a dispatcher. Ryan said that others couldn't handle the pressure, but her daughter came from a family of police officers and firefighters and took to it.

On top of that, Cooper took care of Ryan. They live on the same property in separate houses, and Cooper helped keep her affairs in order as her memory has gotten worse.

“All the pressures were on her, and by her nature, she took them all on," Ryan said. "That’s just who she is, and the rest of the world isn’t like that, and she just got disappointed time and time again.”

Toward the end, the harsh working conditions as a dispatcher started to get to Cooper. She looked at other jobs but would have lost her seniority and the pay her family depended on if she left. She was hoping to retire in the next five or six years.

Ryan said Cooper was terrified to return to work but didn't feel like she had a choice if she wanted to support the family. She spent Sunday next to her daughter's hospital bed, waiting for her to pass. Due to visitor regulations, only one person could be there at a time, Cooper's husband had to wait downstairs. She stayed until the hospital kicked her out for the evening.

“She’s just a good person," Ryan said, "who doesn’t deserve what life gave her."

Read the March 5 follow-up story: Phoenix Investigates Working Conditions After 911 Dispatcher's Health Failure