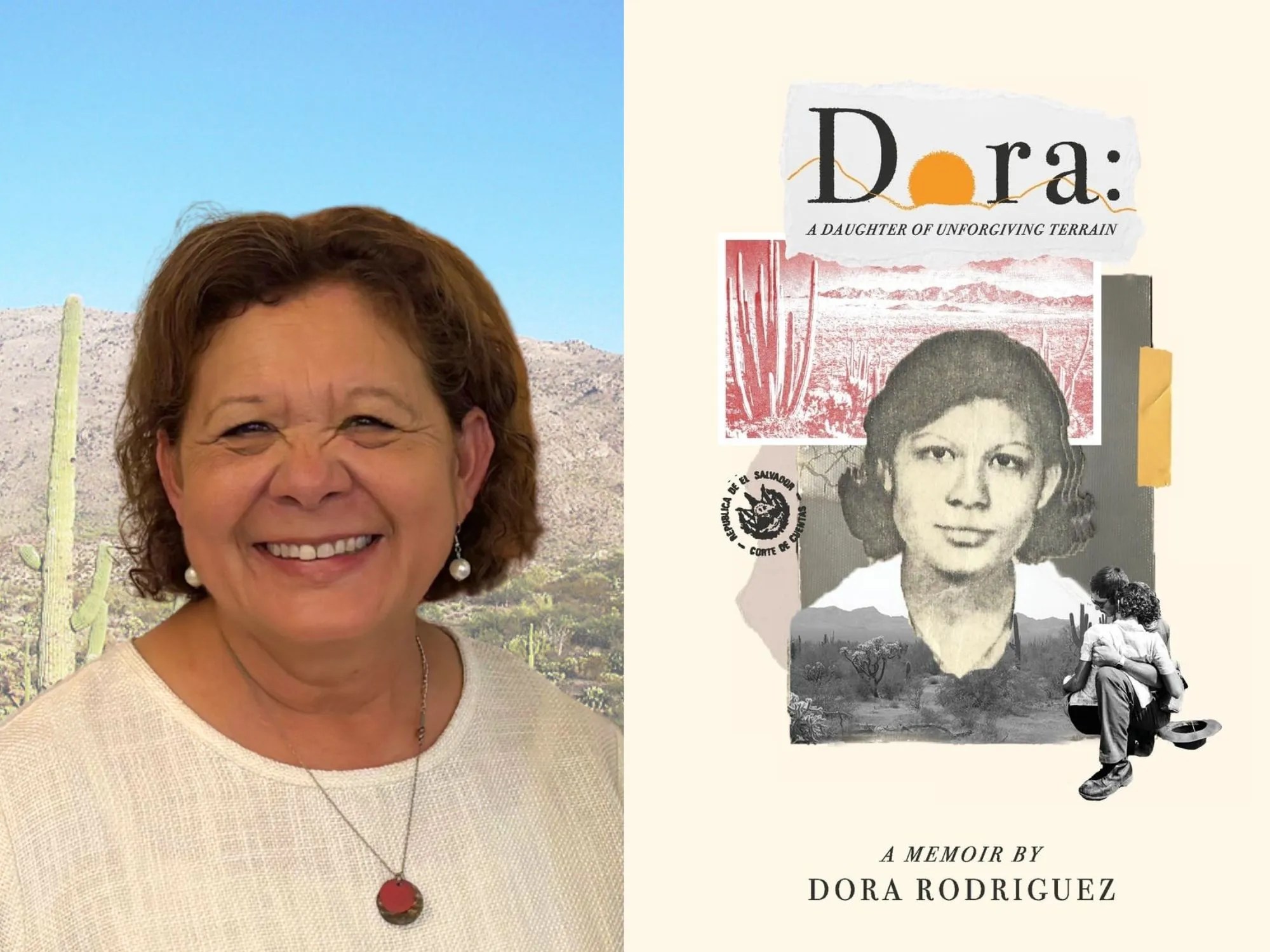

Dora Rodriguez

Audio By Carbonatix

This story was originally published by Arizona Luminaria.

In the summer of 1980, Dora Rodriguez almost died in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Along with a group of 30 people, most of them having fled violence and the beginnings of a gruesome civil war in El Salvador, she had just crossed the border. Rodriguez was 19 years old.

As the group set out into the desert, Rodriguez writes in her recently published memoir, “Dora: A Daughter of Unforgiving Terrain,” “We were utterly dependent on the two Mexican smugglers to take care of us, and we were beginning to understand that this would not be a simple walk to freedom.”

The group soon lost their way, and Rodriguez and the others spent a few harrowing days baking under the sun, desperately searching for shade, clawing at desert plants for moisture – reduced to drinking urine and cologne. She watched 13 of her friends and companions die.

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

The memoir, co-written with Abbey Carpenter, was released in early July and details the traumatic and deadly experience in the desert.

It is a reality suffered by tens of thousands of migrants who have crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, dying in their search for safety, freedom or jobs in the United States.

Rodriguez was rescued, spent a week in a hospital and then was booked into the Pima County jail before humanitarian rights groups bailed her out.

While it took her months to physically heal and decades to come to terms with what she went through, she says she was never defeated.

Her experience pushed her to become a social worker, raise five children and foster many more, as well as establish her own migrant rights organization, Salvavision – all of it from her home in Tucson. While much of the book focuses on the desert experience, what Rodriguez learned from it, how it shaped and fortified her and inspired her to a career of service, is the book’s ultimate takeaway.

“I always had an organizing spirit and a passion for creating better places for people,” Rodriguez writes.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Arizona Luminaria: The first sentence of your memoir reads, “I heal in honor of my friends.” Why did you start there, and was writing this book a way for you to keep healing?

Dora Rodriguez: Because the lives of these people who died in the desert were taken in such a horrible tragedy. Their families never ever saw them again, never saw where they took their last breath. For me, if I weren’t to write the story, if I weren’t to do the work I do, I don’t know how I would heal. So, it’s in honor of them. And my hope is that now writing the story, they will live after I’m gone. I want their story to be recognized.

I want people to know that people continue to die in the deserts. The three sisters (who were in the group with her, ages 12, 14 and 16, all of whom died) were so young. It’s something that should never have happened, but it did. I don’t know if you heal from this kind of tragedy and trauma. I don’t know, but what I do know is that I am able to share.

How did you get to a place where you could not only talk about your experience, but write a memoir about it, as well as be out in the desert volunteering as much as you do?

I thought I was healed. I thought, OK, this is the past, I’m good, I’m moving forward, I’m doing all this humanitarian work. But when I first returned to that site where I was rescued, I could see every single moment of that tragedy playing out. I could hear the voices. I could hear the screaming. I could see the clothes scattered everywhere.

I could see my friends dead under the bushes and trees. And I broke down and I told the people with me, some of my kids were there with me, I said, “This is it. This is the place.” I could sense it.

It’s very interesting how trauma gets into this compartment of your brain and your soul and your heart. But the moment you touch it or something triggers it, it comes back out. I think that also gave me the strength to talk.

Because if I kept it in this compartment, someday it was going to come out and who knows in what way? And I didn’t want that. I really embrace the fact that I can be out there in the desert helping somebody, or at the border in Nogales, Sonora, or here in our community and embrace all these people from everywhere and each person has their own story.

I think it’s a gift of strength that I have, and I believe I was born with it. I write in my book about being so young and so independent growing up in El Salvador. We all heal differently. What has also helped me is being involved in community.

How has the border changed from that moment in 1980 when you crossed to today?

I’ve always said I don’t give Trump credit for all the cruelty, because it was passed on to him from both Democrats and Republicans before him. The only thing I think is a lot worse now is the racism against us.

I have been here for so long and done everything, gone to school, went to work, retired and I never felt that, from one moment to the next, I could be arrested because I look different or I have an accent. So that’s new. In 45 years of living here, I have never felt that fear.

But the community has also changed, the sanctuary movement, the migrant rights groups. I’m in a community that has the same beliefs I do in working to save lives and working every single day to be present, to be with the people who are suffering because of these border policies. So, I think that that’s where my voice got stronger and I lost the fear to talk about it. It just makes me feel that I am morally obligated to tell my story.

You reconnected with the photographer Michael Ging, who took the photo of you (see it on Threads), seemingly lifeless, in the arms of the Border Patrol agent as you were being rescued. What is it like to look at that photograph? Do you recognize yourself?

I had never seen that photo until I started speaking out about the story. That was in 2019. They took all those photos, sold them, got popular, but we never saw them. At least I never did. I went on with my life. And then in 2019, when I decided to start sharing my story, Bud Foster did a story (on KOLD) and he found that picture in the archive. He says, “I got something to show you.” And I was blown away. I said, “What!? That’s me.” That was the first time I ever saw myself in such horrible shape.

I just said, “Oh shit, I’m lucky to be alive.” Because I look lifeless, you know. … Pero fue cuando me dije, “Es un regalo, la verdad, mi vida.” (But I said to myself, “My life is a gift.”)

How has El Salvador changed over the decades since you first left?

I can see the patterns of authoritarian governments and it scares me to death because my sister, her family, my brothers are still in El Salvador.

This new government in El Salvador is very smooth. Because if you go to El Salvador, the majority of the country loves (President Nayib) Bukele.

We had lost our soul as our country with so much death from gangs. And Bukele cleaned that up. So people in the streets will tell you this is the best we have ever been. We love our president, we love our country. But what is freaking me out is there are no checks and balances in our country. And I’m scared of the same thing here, too. Not enough checks and balances. Too much authoritarianism.

The day after your book was released, you went to the location where you were rescued. Can you explain what happened?

So the day after I launched my book was the day after the anniversary of our rescue. For the last 10 years or so, we’ve been going to place crosses and pay respects at that site, to remember these people who died. I’ve gone with lots of students and universities and delegations that want to hear the story about what happened to us.

But that day, after my book release, we were approached by the park rangers and we were asked to leave, because it’s federal land, a national monument, so you’re not supposed to be driving or you have to have a permit, which is probably impossible to get.

The two rangers were very upset that we were there and I said, “Well, I’m sorry we didn’t know,” and I told the supervisor a little bit of our story, who I was and what we were doing, that we had just finished blessing the crosses with the priest.

And the ranger said to me that we weren’t allowed to be there and I said, “Well, that’s a shame because someone should be around this area because people are dying.”

She was not happy with my answer, but she needed to know that. She ended up giving us a $180 ticket. And I just feel very sad and very scared that they are probably going to decide to take the crosses down because you’re not supposed to have any monuments in the National Park. But right next to our crosses is the huge Border Patrol surveillance tower.

As long as we have these policies and as long as we have an anti-immigrant government, people are going to die in this desert. So we have to be out there.

This article first appeared on AZ Luminaria and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.