Courtesy of John Bueker

Audio By Carbonatix

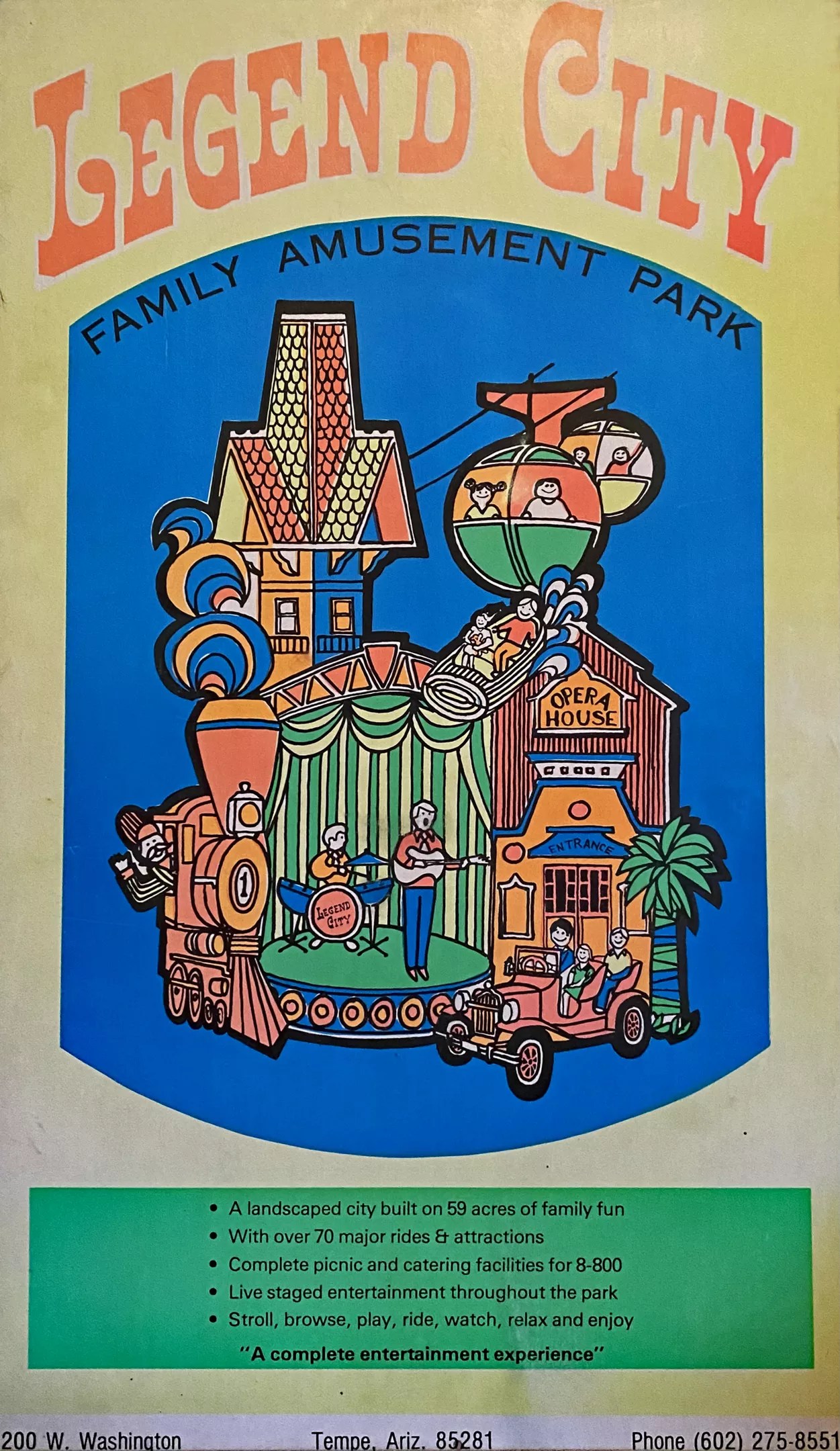

John Bueker’s cache of Legend City memorabilia would make any fan of the long-defunct local theme park jealous. Inside his home office, there are posters, maps, and concept art depicting its attractions. In the kitchen, old signage from an ice cream parlor at the park decorates the walls. And wandering aimlessly is an energetic teacup poodle previously owned by the late Louis Crandall, Legend City’s founder.

Right now, Bueker is pointing out various souvenirs in a 6-foot-tall curio cabinet while it’s gotten harder to score even more treasures these days.

“Legend City stuff has really dried up on eBay lately because it’s gone up in value and [people] are holding onto it, or they remember the park from their childhoods and want a piece,” he says.

And Bueker would know. The Peoria resident has become an unofficial Legend City archivist over the past two decades, creating a website devoted to the park, which operated from 1963 to 1983 on the border of Tempe and Phoenix. He even wrote a book about its history, Images of America: Legend City, in 2014.

Legend City was the brainchild of Crandall, a Mesa advertising agency owner and artist, who envisioned it as an Arizona version of Disneyland riffing on Wild West lore and kitsch. As such, it was filled with themed areas containing Western-themed rides, attractions, and colorful characters.

Patrons could hop aboard a Lost Dutchman Mine ride or float down the River of Legends. Legend City was also the stomping grounds of the late Wallace and Ladmo, the beloved hosts of a namesake children’s program that aired for 35 years on KPHO Channel 5. Along with their dastardly foil Gerald, the pair performed a weekly show at the park throughout its lifespan, interacting with fans and handing out treat-filled Ladmo Bags.

Legend City may have been ahead of its time. Problems with attendance and financial issues during its rocky inaugural year forced Crandall to step away from the park. It changed owners three more times, morphing into more of an amusement park heavy on thrill rides. It eventually closed after its land was sold to Salt River Project.

Bueker, a longtime Arizona resident who visited the park throughout his childhood, says nostalgia for Legend City has only grown in the 39 years since its closure.

“It’s become this cherished thing that was part of many people’s lives,” he says.

Pat McMahon, the veteran entertainer and broadcaster who played Gerald and other characters on The Wallace and Ladmo Show, agrees.

“It was Phoenix’s theme park,” he says. “It was a place created here to appeal to our kids and the kids around Arizona for people to come, spend the weekend there, and have fun.”

In honor of the theme of our annual Best of Phoenix issue, we’ve spoken with former patrons and employees, members of Crandall’s family, and others for a nostalgia-filled history of the theme park.

The late Louis Crandall, Legend City’s founder, in front of the entrance on opening day in June 1963.

Courtesy of John Bueker

Dream Park

In the mid-1950s, Louis Crandall was a man with a dream, which soon became an obsession. After multiple trips to the newly opened Disneyland in Southern California, the Mesa native and advertising agency owner thought Arizona needed its own take on the popular theme park.

John Bueker, author and unofficial Legend City historian: Louis Crandall was an artist and a dreamer. Disneyland really put a light bulb on in his head. He became obsessed with bringing something like it to Phoenix. I’m still pretty astonished he actually made it happen.

Janie Crandall, Louis Crandall’s oldest daughter: Dad always had big ideas. He was a doer. He started several businesses and made things happen. I remember him talking to us about his vision when I was 8 or 9 years old and we’d go to Disneyland quite often, like every three or four months, and he was bound and determined to make this a reality.

Bueker: He went to theme parks around the country, like Six Flags Over Texas, and borrowed ideas from each. Frontier Village in Northern California was a huge influence; he liked their mine ride and copied the architecture of their train station pretty closely. His primary influence, of course, was Disneyland, which was the paradigm for how an amusement park should look.

Janie Crandall: He was always a Western-type guy and loved the beauty of the stagecoach era, so he wanted to build an amusement park with those themes in mind.

Bueker: He got the idea for basing different areas of the park and different rides on Arizona history and legends.

Janie Crandall: One night he came home and says, “I’ve got a name for the amusement park: Legend City.” And I remember telling him, “That’s really dumb.” It came from him wanting to use his initials, L.C., and went along with this frontier-type thing with cowboys and Indians.

Lou Crandall Jr., Louis Crandall’s son: Our dad got a lot of help from a few of Disney’s artists and managers to design the park.

Bueker: They brought in [architect] Randall Duell, who worked on different parks around the country, including Six Flags. Chic Albertson, who was an artist for Disney, designed the map.

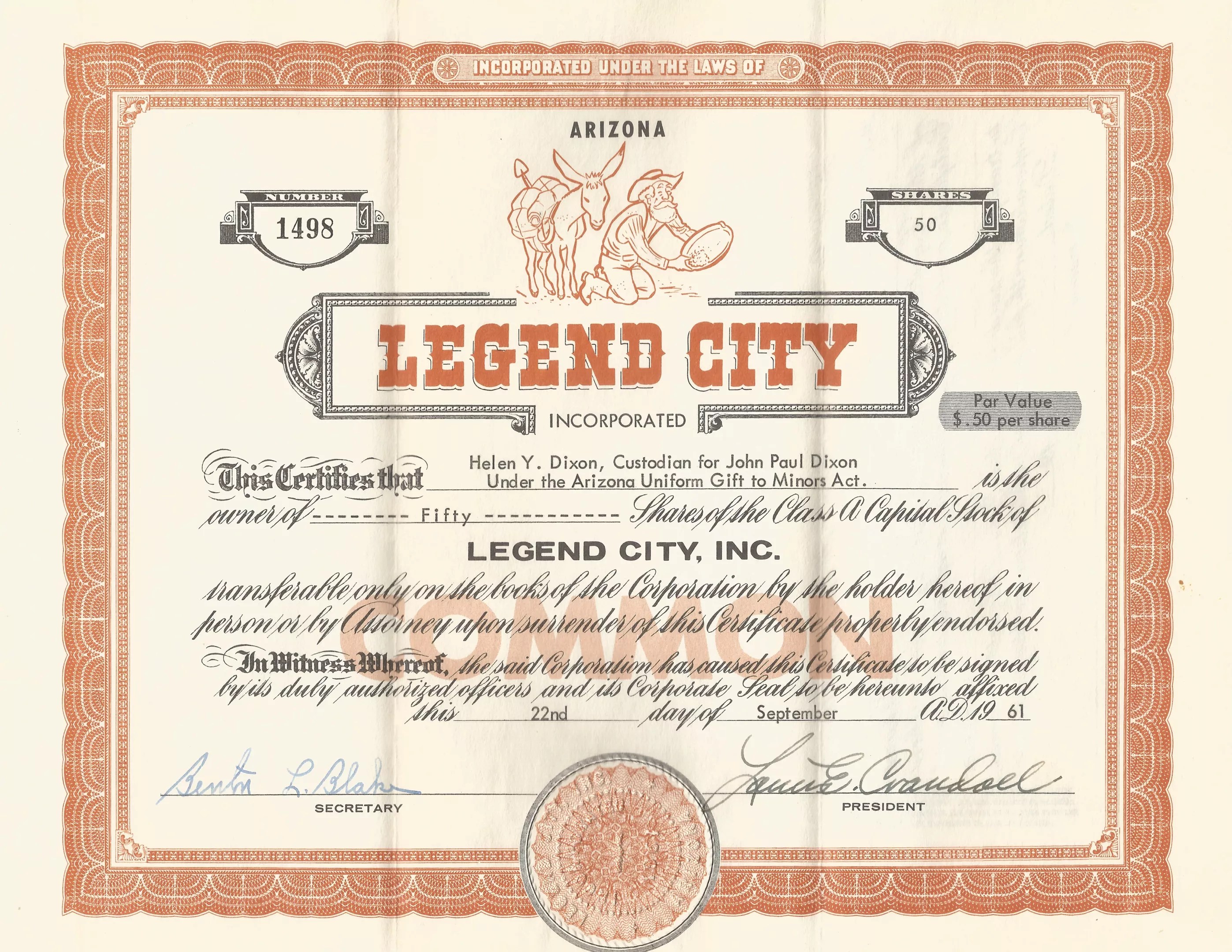

In spring 1961, Louis Crandall announced plans to build Legend City on an 87-acre parcel of land near 56th and Washington streets on the Phoenix-Tempe border. Shares in the park were sold to the public to raise capital.

Bueker: They looked at several locations and Louis was considering somewhere north of Phoenix, but finally settled on [Phoenix-Tempe border] because the topography of the land was suitable. There were these two ravines he wanted to use for a lagoon and a river ride. The price was also right, which helped. They’d started selling stocks to everyone, which is where most of the investment came from.

A certificate for stocks in Legend City sold to raise capital for the park’s construction.

Courtesy of John Dixon

Michael Frost, Legend City employee: There were ads in the Arizona Republic at the time about how you could buy shares of Legend City stock for a buck or less. I knew a few kids who did that.

John Dixon, Arizona music historian and Legend City stockholder: A father of a schoolmate was flogging the stock and came to our house with a presentation. It was based on the idea there was supposedly more traffic along Van Buren and Washington [streets] than the highways surrounding Disneyland. My mom was like, “It’s your money. Do whatever you want.” So I bought 50 shares at 50 cents each. It wasn’t the best idea in retrospect.

An official groundbreaking ceremony for Legend City was held on December 30, 1961, with Arizona musician Dolan Ellis and KPHO’s Wallace and Ladmo entertaining a large crowd.

Bueker: Wallace and Ladmo were involved from the beginning and were a big part of Legend City’s history and vice-versa. Dolan Ellis was everywhere at the time. He fit into the Old West paradigm and could play music appropriate to the theme of the park.

Dolan Ellis, musician and Arizona’s official state balladeer: I was doing a travelogue show on Channel 12, and Western Savings and Loan was my sponsor. Louis Crandall [did their advertising] and he contacted me to write and record music for some 45-rpm records to promote Legend City. I was well known for my Arizona music and knowledge of [local] folklore, so he wanted me to help publicize the new project. I recorded “Desert Silhouette” and “Ghost of Legend City” at Audio Recorders of Arizona with [producers] Floyd Ramsey and Jack Miller.

Dixon: They were trying to drum up business, so why not spend a little money and put out records to get airplay or draw attention? It was a cool promotional item.

Legend City was built over the next 18 months at an estimated cost of $5 million, according to Bueker. (That’s about $9 million in today’s dollars.) Leading up to its debut, Louis Crandall told a local newspaper the “time was ripe” for Phoenix to have its own theme park. Critics disagreed, calling his project a folly.

Bueker: There were a lot of naysayers, people who didn’t think [Legend City] was practical. Some thought Phoenix wasn’t ready for a world-class theme park or didn’t have the population to support it. Louis didn’t let any of it get to him and just kept pursuing his dream.

Janie Crandall: I remember going every day during construction because Dad included the whole family in everything. My mom used industrial sewing machines to create this huge [Legend City] flag. My grandparents and brother were involved with all the concession stands. It felt like they were building something magical. It looked just gorgeous and majestic and just fun.

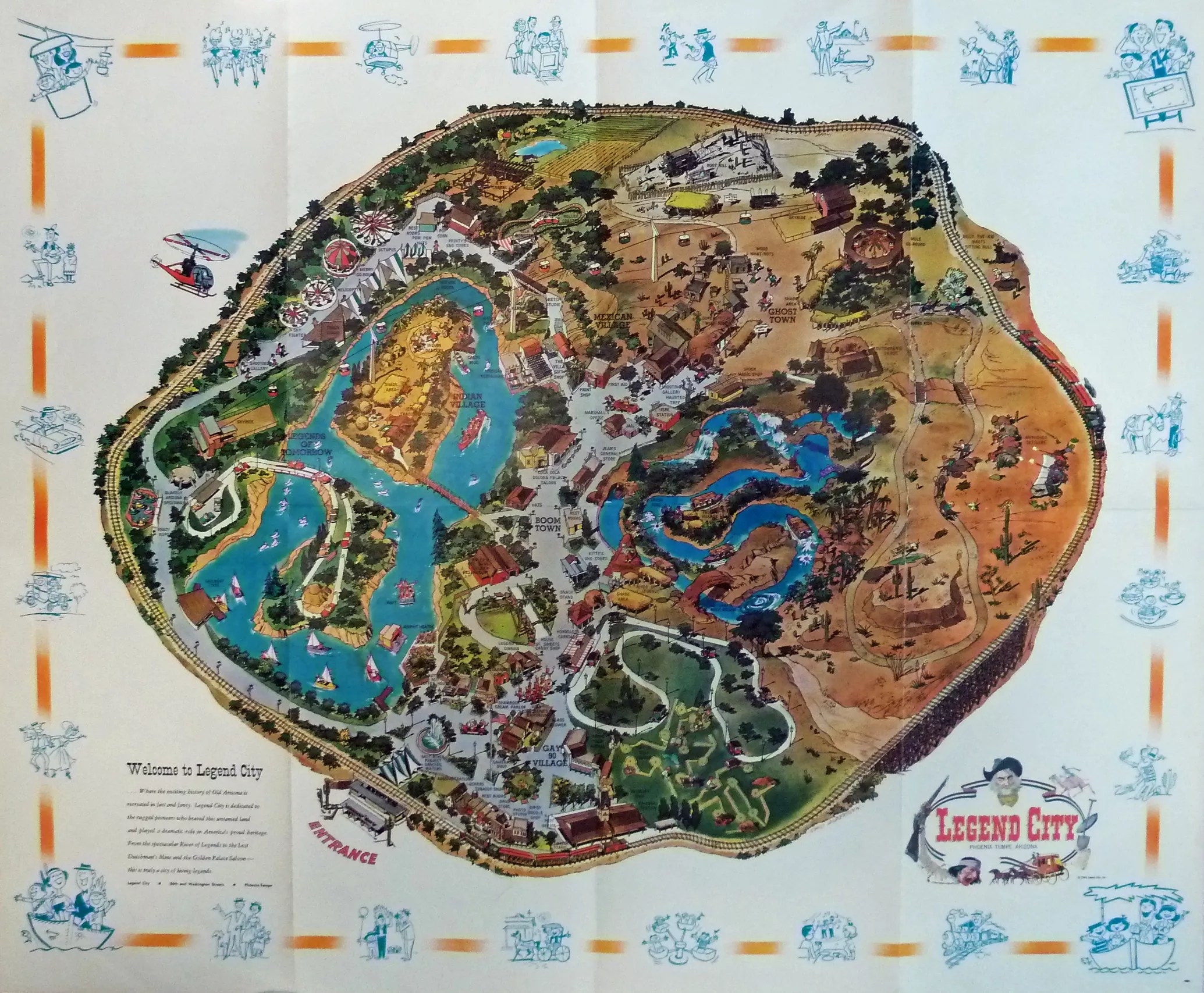

The official Legend City map from 1963.

Courtesy of John Bueker

How the West Was Fun

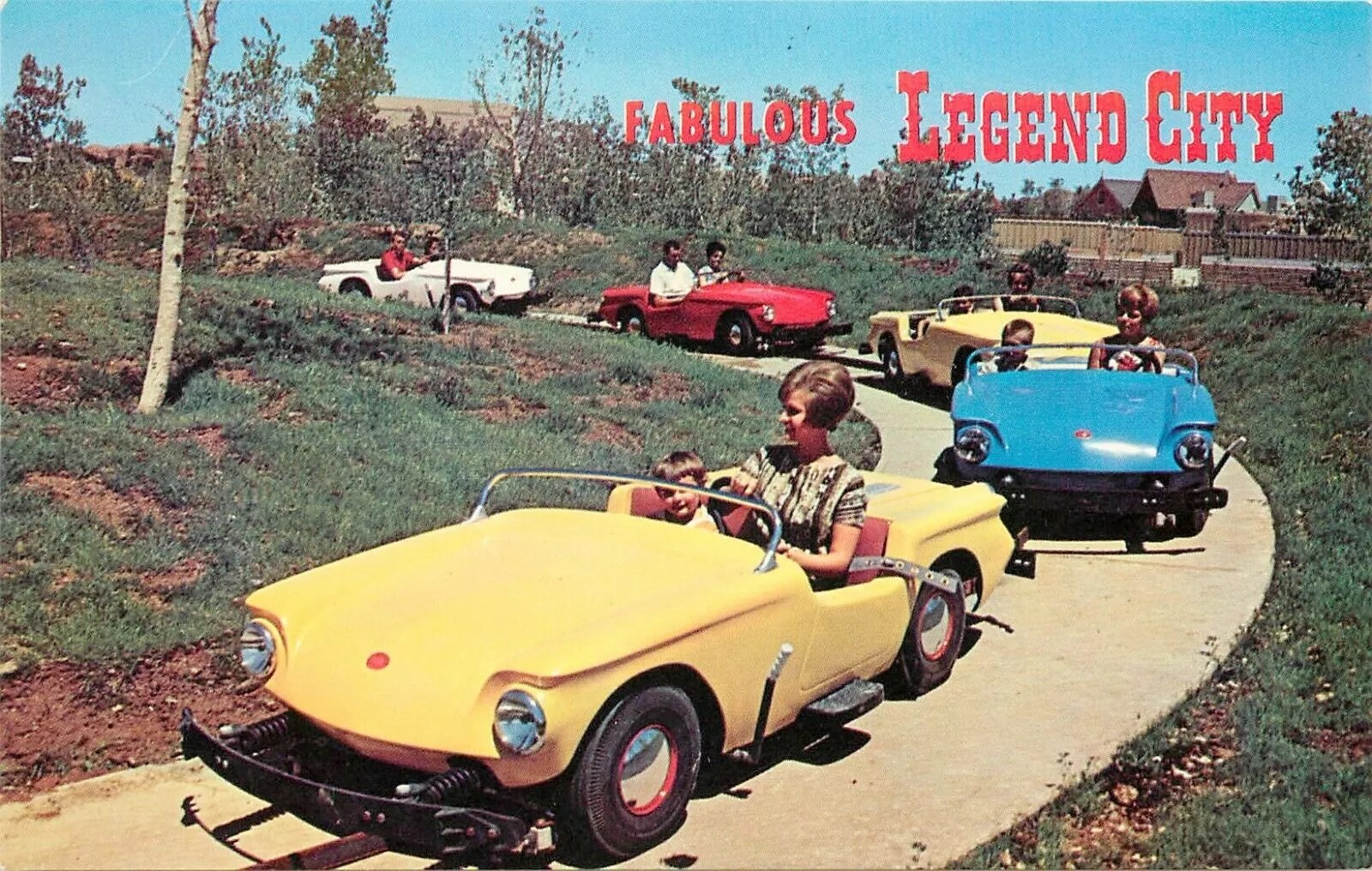

Turnout was huge for Legend City’s opening on June 29, 1963, with more than 28,000 people passing through the front gate. What awaited inside was a Disneyland-like park separated into six themed areas, each offering different rides, attractions, and eateries. Up front was the Gay ’90s Village, a turn-of-the-century-themed analog to the Magic Kingdom’s Main Street, U.S.A. It led to other parts of the park, including the rustic Boom Town and the haunted Ghost Town, as well as the Indian and Mexican villages. Elsewhere, the Modern Era offered the Autopia-like Blakely Arizona Speedway, spinning teacups, and a modest roller coaster. There was also a river boat ride, a sky ride overhead, and a steam locomotive circumnavigating the park.

Beuker: The Gay ’90s had shops, restaurants, and a penny arcade, which was one of my favorite parts as a kid. You could also go on the antique car ride, which was very a popular ride and expensive to maintain because the cars kept breaking down. Boom Town had the Golden Palace Saloon, a marshal’s office, and a general store. The Indian Village was on an island and had Native American dancers performing. Ghost Town had the Lost Dutchman Mine ride, which was extremely popular and the only original attraction that survived the entire 20-year run.

Pat McMahon, local broadcaster, entertainer, and Wallace and Ladmo cast member: It wasn’t some low-budget, medium-sized city carnival-type thing that you would see outside of a supermarket somewhere. This is a real honest-to-God permanent theme park that had terrific rides, was on a pretty spacious piece of property, and had a lot of entertainment and a lot of variety.

Beuker: The area with the more modern amusement rides, which came from this amusement park in Kansas City, Missouri, was so everything wasn’t all Old West. Louis had very mixed feelings about that, but was persuaded in the end to make it a little more eclectic.

Janie Crandall: There was constant activity. They had gunfights in the streets. Strolling marching bands playing. And bandits trying to rob the train when you rode by.

Dixon: It was steeped in kitsch, but so were Knott’s Berry Farm and Disneyland in California. So [Legend City] had the parameters of what people liked – a railroad surrounding the property, a jungle boat river ride, and a frontier town – and were following a certain model.

Inside the Lost Dutchman Mine ride at Legend City.

Courtesy of John Bueker

Beuker: They put a lot of work into the Lost Dutchman [attractions]. The mine ride had a giant spider, scenes with animated skeletons, a graveyard, and other creepy stuff. Everybody loved it. And the Lost Dutchman shack was a tilt-house where the floor moved.

Dave Pratt, local radio personality: It all felt bigger than life in my little-kid eyes. My dad took me on weekends [and] it was my first thrill rides, the first time being scared on a ride, because at that age everything was believable to you. When you went into the Lost Dutchman Mine, it felt real. So to me, Legend City was this fascinating world that existed somewhere in Phoenix but was this separate enchanted land. It was also my first time seeing Wallace and Ladmo live.

McMahon: It wasn’t very long after [Legend City] opened we began doing shows every weekend on the Lagoon [Amphitheatre]. And we loved it because the audience was automatic. Everybody that was in the park at the time, if they could fit into the seating area, would come in for the show and were enthusiastic and part of the fun. And of course, everybody looked forward to winning a Ladmo Bag.

Pratt: I remember my brother Tom won a Ladmo Bag and I didn’t. I was crushed. Those performances had all of my favorite characters, all of which were portrayed by Pat McMahon. And I thought they were real. I believed it. I thought Gerald really was an illegitimate relative of Barry Goldwater. I thought Aunt Maude was real. I thought Captain Super’s muscles were real. My parents never wrecked my imagination and set me straight, which made it a lot more fun.

The late Wallace (right) and Ladmo (center) ride in one of Legend City’s antique cars while Gerald (left) attempts some sabotage.

Courtesy of John Bueker

McMahon: [With] the Legend City shows, we’d try changing things up with different characters, but Wallace, Ladmo, and Gerald would always be there. And the plot was always “Yay! Boo! Bad guy causes the kids to go crazy, good guy wins” in the end. But sometimes Captain Super would come in as the blowhard phony superhero. And sometimes Aunt Maude would come in and read one of those dark stories and would be ushered off the stage after the punchline. But there was always Gerald. You had to have Gerald there or the audience would revolt because Gerald was revolting.

Wallace and Ladmo weren’t the only entertainment at the park. The Golden Palace Saloon and Lagoon Amphitheatre hosted a variety of performers. Can-can dancers and barbershop quartets like The Copper Tones and Devilaires. Sleight of hand from magicians Ed and Nanci Keener. And ventriloquism by Vonda Kay Van Dyke, a future Miss America.

Ellis: I started performing at Legend City right after they opened the park. I was doing my Arizona songs and historic music. I wasn’t there on a regular basis, as I was very busy back in those days. I’d just come back from being in The New Christy Minstrels and was doing six nights a week in nightclubs, so I’d work there on special occasions.

Beuker: It was like a parade of entertainment they recruited locally, some of it [old-timey], some of it more modern. [The late] Serge Huff was the original musical director who brought many of them in, like Vonda Kay Van Dyke.

Ventriloquist and entertainer Vonda Kay Van Dyke with her dummy Kurley-Q.

Courtesy of John Bueker

Vonda Kay Van Dyke, ventriloquist, singer, and Miss America 1965: I worked the show at the Golden Palace Saloon and did two spots: One was [singing] “Hello, My Baby” where I’d go into the audience and sing to some young man. And guys would sit at one table because they knew that’s where I’d be at and would stand in line to sit at the table, which was really fun. The other spot was my ventriloquist act with my dummy Kurley-Q. It was a great experience.

Dan Horn, local ventriloquist and comedian: I remember going as a child after Legend City first opened. I saw Vonda Kay Van Dyke perform with Kurley-Q and I just went crazy. It was the neatest puppet I’d ever seen in my life and I was thoroughly entranced by her and [the] whole illusion. And that’s when I decided that what I wanted to do was be a ventriloquist. That’s where it all started for me.

A Legend City admission ticket from the 1960s.

Courtesy of Tempe History Museum

Rough Ride

The following summer, Legend City began experiencing more ups and downs than a roller coaster. Despite welcoming 500,000 guests in its first year, the park was facing dire financial woes. Unforeseen expenses and bad business deals, compounded by revenue shortfalls and pricey upkeep of the popular (and frequently broken) antique car ride caused it to hemorrhage money and accrue massive debts.

Beuker: They got into financial trouble pretty quickly. There were many cost overruns with building the park and it didn’t get the consistent attendance or revenues they expected. Phoenix just didn’t have enough of a population in 1963. People came out, but not as much as they anticipated. To me, more than the heat or anything else, that’s what doomed Legend City: It didn’t get off to a good viable start and never really recovered.

Lou Crandall Jr.: My father said [1963] was the coldest fall and winter they’d had in Phoenix in a long time. So after the summer, it got really cold and people weren’t coming out.

Bueker: There was also some financial malfeasance by some of the people involved, but not Louis. He was a completely honest individual, the sweetest guy you’d ever know, and a creative, talented man. But he was not a businessman. He just wasn’t suited to running the park.

Lou Crandall Jr.: He just didn’t have enough running capital. He went to all the investors and said, “We need more money,” and they told him it wasn’t there. They originally had enough for two phases but pretty much spent all of it on one phase. My father wanted to get the second phase of the park started because he felt it was going to take off the next spring and summer. No one would give him any money to run the park. He went to the investors. He even went to [then-Arizona Governor Paul Fannin]. The answer was always no.

Bueker: By late ’64, Louis was gone. He gave over control of the park to the board of [directors] and left for Utah.

Janie Crandall: Dad got commissioned to go up to Provo and build a ski resort, so that’s what he did.

He was sad and really regretted he couldn’t keep it going.

Bueker: [The board] tried stabilizing things by selling more stock and securing more loans. Ironically, for the next year or so, revenues went up. But it wasn’t enough to stave off the creditors and they went into bankruptcy.

Dixon: So my stock wound up nothing but a worthless piece of paper. It was a tough lesson. It’s probably worth more now as paraphernalia.

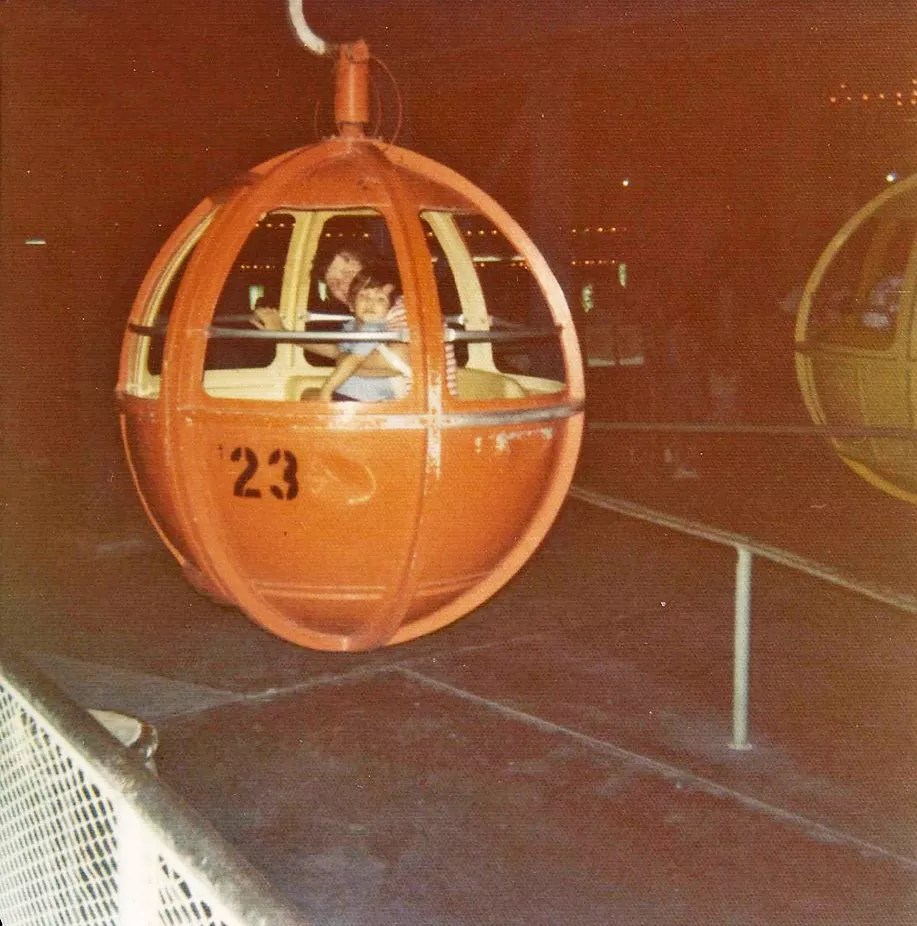

Valley resident Patricia Ordoñez riding the Satellite Sky Ride with her son Glen Ordoñez in the late 1970s.

J.R. Ordoñez

More Owners, More Rides

Legend City closed in September 1966 and was ordered to be liquidated by a bankruptcy court. It went dark for two years with no hope of revival. Enter Sam Shoen, the late entrepreneur behind U-Haul, who bought the park in 1968 for less than $1 million and began making changes. When it reopened a year later, things were different. The Western elements were dialed back or ditched altogether. New rides were added to the mix as it became more of an amusement park. And waves of teenagers and college kids were hired as employees.

Bueker: That’s really what saved Legend City and why we had it as long as we did. Sam Shoen sunk a lot of money into it, repaired and repainted everything, and was clearly trying to rebrand the park. He actually was thinking about renaming the park [to] Frontier Funland, but cooler heads prevailed. He also bought a bunch of steel rides and hired a younger staff.

Don Enz, former Legend City employee: There were good changes. They did away with things that weren’t effective to spend money on, like some of the river boats and rides. It took a lot to make the water clean, so I don’t think it was healthy having people in canoe rides.

Mike Delamater, former Legend City employee: A lot of the new rides coming in were from an old amusement park in California called Pacific Ocean Park. The [Satellite] Sky Ride came from there, which is why the [gondolas] look like diving bells, because that was the theme of Pacific Ocean Park. They hired a lot of children of U-Haul employees, and my mom was a legal secretary there.

Frost: In the summer of ’69, they ran an ad at ASU’s employment office looking for college kids to work. My wife worked in the hat shop and I got hired as a security guard. I’d catch a lot of fence-jumpers and keep the peace, but my biggest thing was guarding Wallace and Ladmo and particularly keeping the kids from killing Gerald. They’d go nuts when he came out and would try to get to him.

A Legend City poster circa 1969.

Courtesy of John Bueker

Enz: I was working security and one of the unpopular things I had to do was go put bumper stickers on the cars in the parking lot. It didn’t go over very well.

Delamater: The first job I had was as a ride operator. One thing I learned was when people puked, you’d stop the ride and hose it down, giving you a break. So the goal then became, see how many people you could get sick. And the guy who operated the Tilt-A-Whirl figured you could make the cars spin faster by turning off and on the motor. So he and I used to have contests to see who could make people sick [the fastest].

Paul Michaels, Legend City patron: The cool part was you could stand under all the thrill rides at Legend City and collect change that fell out of people’s pockets. That’s how you’d get soda and snack money at the park. But you also wanted to be careful because people were throwing up, too. I think they called that part of the park “Barf Row.”

Andréa Leona, former Tempe resident: Tempe back then was just small and dusty. So Legend City was the default place to go, especially for teenagers. It was always hopping. There wasn’t a lot to do. You had to make your own fun. My whole family used to go or my older sister would take me. And when I got older, I’d hang out there with my boyfriend. It was the only hotspot in Tempe back in that era for younger people. It was something you could do every weekend.

Michaels: I started going with my family in 1970. It was just one of those family places to go and a hell of a lot cheaper and easier than going to California. So Legend City was like the budget Disneyland.

Bueker: They still kept a bit of the Western stuff. The river ride was rechristened Cochise’s Stranglehold. They still had gunfights and stunt shows. But for once, the park was successful.

The Sidewinder roller coaster, which operated from 1978 onward.

Courtesy of John Bueker

In 1973, Legend City was sold again, this time to Continental Recreation, a Japanese-owned ride manufacturer. It wasn’t long before the park changed hands.

Bueker: My understanding is Continental just wanted to use the park to promote and try out their amusement rides and weren’t really interested in running Legend City on behalf of the locals. It didn’t last very long, understandably. The next owner, Bill Capell, came along in 1975 and bought the place. He continued the trend toward making it more of a general amusement park and away from Louis Crandall’s original vision for Legend City. They added more of the carnival-type rides and the Sidewinder, which was a world-class roller coaster.

Frost: [The Capells] were from a carnie background. They bought [Legend City] and turned it more into a carnie kind of operation.

Neil Bourque, former Tempe resident: The one ride I loved was the Musicfest, which lots of amusement parks have. It was this fast-moving kind of carousel-y [Matterhorn-type ride] with cars moving on a circular track, but they’d blare rock music really loud. All the stoners and burnout kids would be on it, so you’d be afraid to ride, but it was cool.

Deb Dunlap, former Legend City employee: It was a fun job in high school. I started out in the ticket booth, which sucked, and then I went to rides, and that was fun. I probably did the bumper cars the most. We’d go on our day off during the week because weekends were busiest; you got in for free, rode for free, and got in front of the lines.

Musicfest, a Matterhorn-type thrill ride, at Legend City.

Courtesy of John Bueker

Delamater: A lot of crazy stuff went on at the park.

Dunlap: I was working the [Satellite] Sky Ride one day and there’s this bad windstorm and we had to get everyone off. And as I was doing that, these kids were crying about how someone had fallen off. I guess the wind had blown one of the gondolas off the track, it had dropped down, the door flew open, and a kid almost fell out but his parents caught him by the arm.

Not every mishap on Legend City’s ride had a happy ending. On August 10, 1977, a door on the Zipper ride opened, causing 12-year-old patron Esther Urbalijo to fall to her death. Her sister Inez, then 15, was also injured. Their family was awarded $1.3 million from a lawsuit over the incident. It wasn’t the first ride-related fatality at Legend City – an 18-year-old student nurse fell to her death in 1969 – but portended the downward trajectory the park was headed on in its twilight years.

Dunlap: I was there when the girls fell off the Zipper. The door was latched with a cotter pin and there were no seat belts. They tried to say the ride operator was drunk and threw the cotter pin. I testified at the trial and said I’d seen him earlier that day and he wasn’t drunk. It was just this freak accident.

Bourque: When the park was in its later years, everything seemed kind of cheap. When you were a kid, the Lost Dutchman Mine ride looked really good back then, but every year you’d return and another piece of it was missing or the sound loops would be off or weren’t working at all.

The original Compton Terrace in 1980.

For Those About to Rock

By 1979, the Capells leased a 30-acre portion of the park off the entrance to local entrepreneurs Jess and Gene Nicks to create the 20,000-person concert amphitheater Compton Terrace.

Pratt: When I moved back to the Valley in 1979 to work at KUPD, Legend City had been struggling a lot, going through different ownership and financial difficulties. It certainly wasn’t the same as I remembered.

Jess Nicks, Stevie’s dad, and his brother [Gene] decided to put this concert terrace inside what was Legend City. [Local concert promoter Doug Clark] helped bring the shows in. And Legend City was open to the idea because, at this time, they had to get creative to survive.

Leona: As a teenager, I mostly went to [Legend City] for Compton Terrace concerts. I think you’d get into the park free with a concert ticket. We’d show up early and have a couple of rides, but we were really there to see AC/DC or Judas Priest or Elton John. They used to get amazing shows there.

Wayne Rainey, local developer: I saw my first concert at Compton Terrace next door, which was Fleetwood Mac in 1980 on the Tusk tour. It was life-changing and probably my favorite memory of childhood.

Pratt: We brought The Go-Go’s in ’82 and I took them onto some rides [before the show]. I think it was a Saturday, and Legend City was shut down in the daytime during the off-season. And as we were riding, they were talking about doing a video there. So I got to show The Go-Go’s around Legend City. How cool is that? I was a 20-year-old with a mullet.

Mark Zubia, local musician and former Legend City patron: I worked at one of the concession stands [at/near Compton Terrace] when there were shows; just like a part-time job. The concession stands were in Legend City. It was chaotic, a bunch of teenagers. When I wasn’t working, I’d go there. Just chasing girls, sneaking in joints; just typically teenage fun.

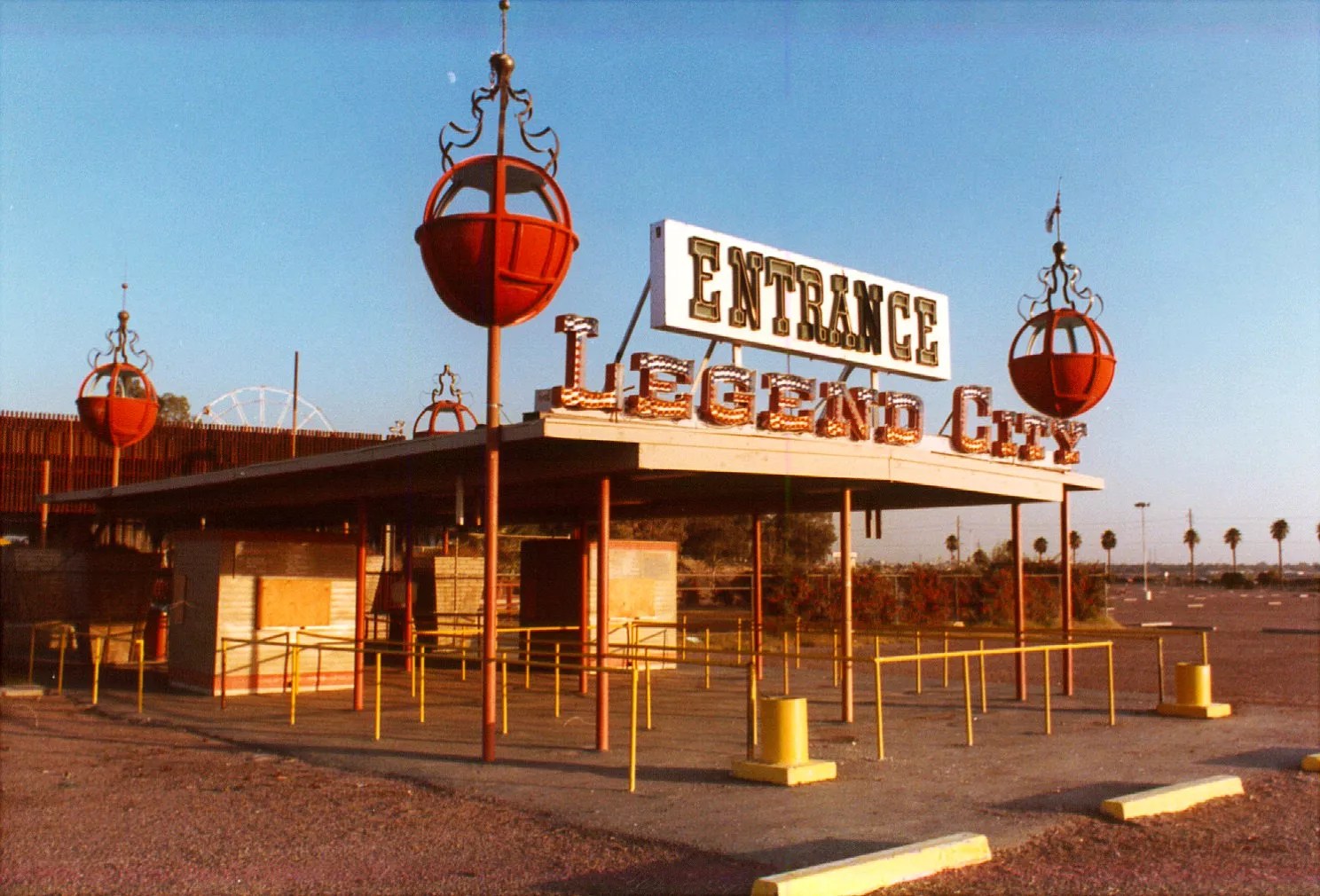

Legend City’s front gate after the park’s closure in 1983.

Courtesy of John Bueker

End of the Ride

By the early ’80s, things had gotten worse at Legend City. Most of the shops were closed, blight was everywhere, and rides were falling into disrepair. In April 1982, a Tempe Fire Department official declared the park a fire hazard after a blaze engulfed an abandoned ride.

Todd Baty, former Legend City employee: A lot of things had [become] run down. All of the little gift shops and novelty stores were pretty much abandoned. The Sidewinder roller coaster would only run if it had the weight of passengers in the cars. Occasionally, after it rained, the tracks would rust. So before we allowed any customers on, they used employees to give it a test run. I remember being in the back car and having to get out and push it over the next hump before it got going again.

In June 1983, Salt River Project announced a $21.5 million deal to purchase the property for its new corporate headquarters. Three months later, Legend City permanently closed on September 4, 1983.

Bueker: The Capells did fairly well with Legend City financially. They didn’t make a fortune, but they made a profit. Louis Crandall first got it for a song, but it was worth tenfold in the early ’80s. The real estate was so valuable SRP wanted the land, they had deep pockets, and it spelled the end for Legend City.

McMahon: Legend City lasted 20 years. And like The Wallace and Ladmo Show, it continues to live in the hearts and minds of people everywhere. It’s astounding to me. To this day when it comes up in conversations with people, they always ask, “Why hasn’t somebody done a new Legend City?”

Horn: I was still taking dates to the park right up to the months before it closed.

Bueker: There’s an idea that Louis Crandall and Legend City were ahead of their time. The Phoenix area probably wasn’t quite ready for a park like that. One of its biggest legacies is we still don’t have a major amusement park in Phoenix, 40 years after Legend City disappeared. We periodically hear people making proposals and plans to build something, and it never seems to materialize. We deserve to have a world-class amusement park here, but we don’t.

Editor’s note: Some quotes have been edited or condensed for clarity.

John Bueker’s book Images of America: Legend City is available at arcadiapublishing.com.