Jim Louvau

Audio By Carbonatix

Raheem Jarbo controls the packed crowd at The Rebel Lounge in Phoenix like his own personal video game.

The

“Now put up your hands!” he declares.

Dutifully, they obey his command, mimicking the gesture in time to the jaunty, warbling chiptune beat coming from The Rebel Lounge’s sound system.

It’s an evening in late May and Jarbo, better known as Mega Ran, is in the midst of a set opening for nerdcore legend mc

“I thought I was in love before / But I love you more, so baby come aboard / And go away with me, so I can make you see / What you mean to me, and baby we can be free,” he sings. “Ah-whoa-oh, under the sea / Ah-whoa-oh, just you and me.”

Like a lot of the songs in his repertoire, this one is inspired by video games. (Namely, a character from Capcom’s classic Mega Man series, which is the source of Jarbo’s moniker.) The track’s backing beat and lyrical content come from the Mega Man franchise, as does the oval-shaped toy arm cannon (known as a “Mega Buster”) that Jarbo slips onto his hand and points at the crowd after exclaiming, “Now it’s time for battle!” and singing the rest of the song.

Jarbo’s been rapping about video games for years. Truth be told, it’s been his biggest claim to fame for more than a decade now. He’s created tracks and albums devoted to such games as Final Fantasy VII, Sonic the Hedgehog, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, and Ghouls ‘n’ Ghosts.

But he’s mostly known for his many Mega Man-inspired raps. He was the first hip-hop artist to create them, and they made him famous in the nerd world.

After moving to the Valley to work as a special-education teacher in 2006, the Philadelphia-born rapper created and released a Mega Man concept album titled Mega Ran a year later.

Since then, Jarbo’s created more than 130 songs about Mega Man, which earned him a Guinness World Record earlier this year for creating the most commercially available songs to reference a single video game franchise.

Games aren’t the only geeky subject matter that

These songs fall into the category of nerdcore, a subgenre of hip-hop focusing on anything and everything geeky, ranging from science fiction to space exploration, as well as challenges and issues faced by geeks. Nerdcore (also known as

An infectiously fun atmosphere fills the venue as members of the audience – many of whom wear geeky T-shirts referencing Star Wars, Star Trek, and other nerdy franchises – dance to the beat and sing along to Jarbo’s songs, like when he busts out with the theme song to The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, a TV show that starred fellow Philadelphian Will Smith. Another fun moment comes when Jarbo performs a freestyle rap based on random objects that the crowd hands him.

The shows reflect Jarbo’s happy-go-lucky and positive attitude. He constantly has a smile on his face, either when performing onstage or hanging out at his merch table afterward interacting with fans. Following his set at The Rebel Lounge, for instance, Jarbo warmly greets dozens of fans and happily discusses everything from what he’s working on these days to his favorite wrestlers. He also gives out hugs, even if he’s covered in perspiration after his performance.

The Rebel Lounge show, sweaty hugs and all, is the beginning of a busy summer for Jarbo, including visits to E3 and other cons around the U.S., going on a mini-tour with local rapper Bag of Tricks Cat in support of their collaborative album Emerald Knights 2, and visiting New York City to attend the WWE’s SummerSlam pay-per-view later this month.

He’ll also hit up several video game events throughout the summer, including this year’s Game On Expo in downtown Phoenix from Friday, August 10, to Sunday, August 12.

As his rap output indicates, Jarbo’s a lifelong video game fan. He spends several hours a week playing games on his PlayStation 4, SNES Classic, and Nintendo Switch.

But video games have given Jarbo more than hours of entertainment and fuel for his career. They also helped save his life, he says.

Jarbo was a latchkey kid who grew up in Philadelphia in the late 1980s and early ’90s obsessively playing Nintendo and other systems. The addiction helped keep him off the streets of the inner city.

Nerdcore and games have also given him a purpose in life, as Jarbo (a self-described “teacher/rapper/hero”) uses both as vessels to spread his messages of positivity and embracing your inner geek. It’s meant a lot to his enormous base of fans, who cite Jarbo as an influence and inspiration.

As much as Jarbo has enjoyed his stardom, he worries about being pigeonholed as just another nerdcore artist. He also has attempted to grow as an artist, hence non-geek albums like RNDM and the recently released Emerald Knights 2. Both albums rocketed up various Billboard charts, indicating that Jarbo’s success isn’t limited to just geeks and gamers.

Now 40, he tells Phoenix New Times that he’s been considering his legacy and might be moving away from

“I don’t want my final chapter to be, ‘Well, he really liked Mega Man,'” he says. “I’d really like it to be a little more than that.”

But does that mean giving up video game raps for good?

Once upon a time, before beats and the rhymes / And before there was ever any Random / There was a boy in the hood, who always did good / So the bullies of the block couldn’t stand him. — Mega Ran, “Dream Master”

Unlike Mega Man, Jarbo’s tale doesn’t begin in the year 200X, but rather 1977. Born to Doris Jarbo, a single mother, he grew up in the West Oak Lane section of Philadelphia, a predominantly middle-class, African-American neighborhood that gradually grew sketchier as he got older.

It was the sort of tight-knit block where everyone looked after each other. “The old ladies would be watching out for us kids all the time,” Jarbo says. “They’d make

It was the only supervision he had at times, save for the occasional babysitter. His mom worked “crazy hours,” first as a Honeywell factory worker and later as a nursing assistant, and Raheem only saw her an hour or two a day. As a latchkey kid, his afternoons were filled with cartoons (G.I. Joe and Transformers were favorites), action figures, and video games. Lots of video games.

“I was spoiled, I think, because of my mom never being home. She felt bad about it and wanted me to have the best,” Jarbo says. “She’d always tell me, ‘Yeah, we don’t have a lot of money for things,’ but I’d still get stuff.”

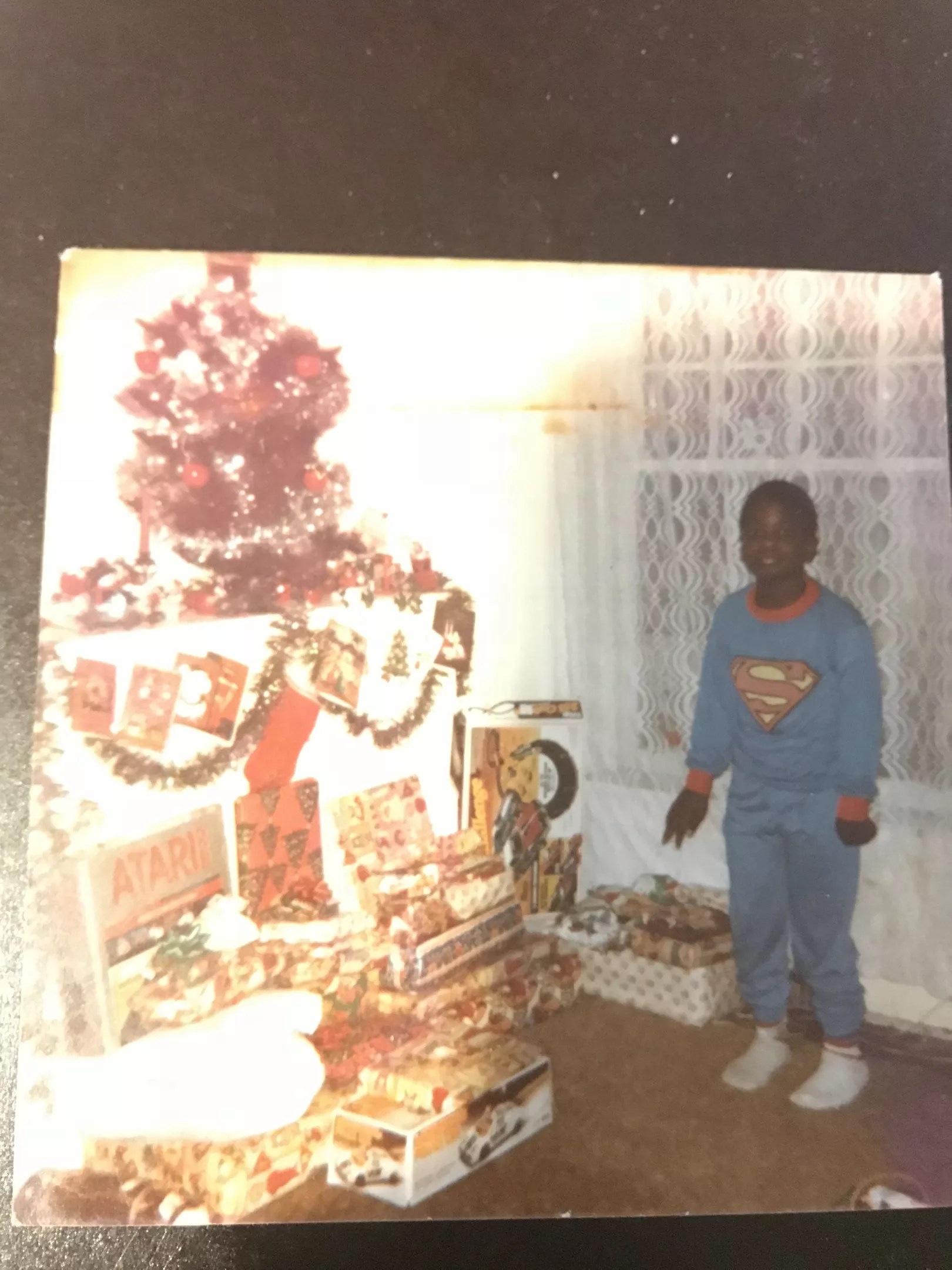

And the first video game system he got was the original Atari 2600, which he got one Christmas and played religiously, spending hours being chased by the ghosts of Pac-Man or taking down the enemy fortress in Yars’ Revenge.

Then came the Nintendo Entertainment System. His mom bought it on a whim one afternoon in 1989, despite their car breaking down and the legendary console’s then-hefty $149 price tag. It was a moment that helped define Jarbo’s childhood and later affected his life.

“It was really the NES that got me,” he says. He’d rent games from the neighborhood video shop or play them with his cousin Howard, who’d later introduce him to such influential pursuits as hip-hop and watching professional wrestling.

When it came to buying games, however, there were a few restrictions.

“The deal was I couldn’t get any new games until I beaten the one I had. And back then, video games were ridiculously hard,” he says. “So I’d only get new games at Christmas, but only if they were from the $19.99 bargain bin.”

Courtesy of Raheem Jarbo

That includes the original Mega Man, which he picked up in 1989. The game was the first entry in the long-running action-platform series, which involves a blue-suited hero battling rogue robots created by a mad scientist bent on world domination. The series had a substantial influence on Jarbo, particularly the phenomenally popular Mega Man 2.

“It was so colorful and all the bosses looked so dope,” he says. “All those great tunes from the soundtrack were stuck in my head.”

They also found their way onto mix tapes that Jarbo created.

“I used to take my recorder,

He’d rock his Walkman so often that neighbors called him “Radio Raheem,” referencing the boombox-toting character from Do the Right Thing.

Jarbo stood out in other ways. Back in the day, he was “this snaggle-toothed, chunky kid with thick glasses” and a frequent target for bullies. He developed a few ways to deal, like becoming a class clown.

“I was pretty witty, but I had to be,” Jarbo says. “In middle school, if you don’t learn to hold your own, you’re mincemeat. So my defense mechanism was

Sometimes, he’d mouth off too much in class, and Jarbo’s mom and

“

Jarbo also used video games as a way to make friends, inviting classmates over to play Nintendo or sometimes shoot hoops. He had a big turnout at first, which gradually decreased because, in part, to what was happening in Philadelphia at the time.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, a massive crack cocaine epidemic swept the city and violent crime skyrocketed as some inner-city residents turned to

“Less and

Jarbo avoided becoming involved in violent crimes by choosing to camp out at home, controller in hand. It kept him out of trouble.

“I can remember moments where, because I’d be home playing Tecmo Bowl or Metroid or whatever, I wasn’t at the schoolyard when someone got shot or at the park when a bunch of kids got arrested or a fight broke out. While thing

Jarbo eventually began hustling, albeit as an up-and-coming rapper. In 1994, after hearing such landmark albums as

“One afternoon, we were hanging out and my friend Big Al was like, ‘Let’s all write

True to form, it also featured a shout-out to a video game, namely Street Fighter II. Not that it helped save his weak verses.

Jarbo in Philadelphia in 2008.

James Johnson

Instead of rage-quitting after his poor performance, however, Jarbo kept at it, determined to improve. “It made me work that much harder. I went home, asked my mom for a notepad, and wrote raps like crazy,” he says.

Jarbo kept writing, and not just “silly braggadocio stuff.” He also began making songs of a more socially conscious nature on a four-track recorder he bought from Radio Shack, rapping with friends over looped and sampled versions of other people’s beats. That gave way to releasing mixtapes, first as “The R,” then “Rated R,” and eventually “Random,” a reference to the villain from Marvel’s X-Factor comic that became his moniker of choice for more than a decade.

“It drove my friends nuts,” Jarbo says. “They were always like, ‘Man, you make so many tapes. We’d leave you for two days and come back and you’ve already got a new one.’ I just couldn’t stop.”

That was true even while attending Penn State University to get a degree in English and African-American studies from 1995 to 2000. Jarbo’s mother wanted him to press pause on making hip-hop and playing games in order to focus on studying, but he kept recording on weekends, over breaks, and even on the sly in his dorm room. He was still doing it after becoming a special education teacher in 2000 while also working a side gig as an engineer at a Philly recording studio.

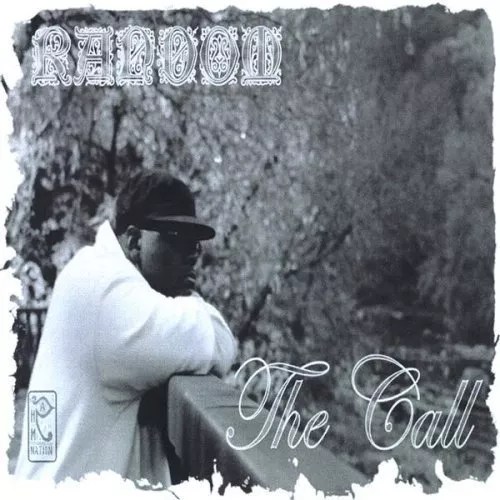

Jarbo’s first major album, The Call.

RAHM Nation

Melvin Raymond, who performs and produces as DJ DN3, began collaborating with Jarbo around this time and remembers being blown away by the rapper’s skills as a rapper and lyricist.

“I’d just throw him some beats and he took off with some amazing rhyming [on the spot]. I was like, ‘Wow, this guy can come up with songs that fast!?!'” Raymond says. “I worked with other artists, and it’d take them weeks or months to get back to me with a song after I gave them beats. But this guy was writing songs the very same day. I was spoiled working with him.”

The two worked together to craft Jarbo’s first big album, 2006’s The Call. The 19-track effort took two years to make as Jarbo poured his heart, soul, and savings into its creation. “It was inspired by everything I was thinking, feeling, and listening to at the time, equal parts Nas, Biggie, Wu-Tang, early Kanye with the sampling, Dead Prez … whoever,” Jarbo says. “It was all about life, my struggle, hard times, good times, mostly the rough times. When I finished it, I felt like, ‘Man, this is a little depressing, it’s just so somber.'”

The Call was a modest success in the Philly hip-hop

“He was kind of disgruntled because The Call didn’t win anything,” Raymond says. “It just took a lot of wind out of his sails. At that point, he was saying, ‘I don’t know if I can make it in Philly.’ It kind of felt like a dead end to him.”

Months after The Call‘s release, though, Jarbo hit a nadir. “It took me so long to get started and I literally came to a point where I wanted to walk away from everything and just hit the hard reset,” he says. “Just that quickly, I got burnt out and wanted to move on.”

Fed up with brutal Pennsylvania winters and feeling blasé about hip-hop, Jarbo moved to Phoenix in August 2006 for a teaching job. And that’s where everything changed for him.

So he decided to combine his love for the games and raps / Open his soul up and let ’em in / Then he chopped up some 8-bit sounds, put it down / Now Random is now known as Mega Ran. — Mega Ran, “Dream Master”

The day in mid-July before Jarbo heads to Ohio for this year’s Gathering of the Juggalos is a busy one for the rapper. He’s trying to speed-run through

“Yeah, it’s going to be a pretty late day,” Jarbo says.

He spares a few minutes to show off a narrow nook in the two-bedroom home near downtown Phoenix that he shares with his wife, Rachel. The area functions as an office, occasional studio, and trophy room, and is a sight to see if you’re big into Mega Man, Mega

“Yeah, someone created a mod of Mega Man 2 where the lead character is me, running around with glasses on and shooting discs like CDs,” Jarbo says.

There’s even more stuff in storage. “My wife didn’t want our entire living room to become a Mega Ran shrine,” he jokes. He’ll make room for his Guinness World Record plaque, however.

Opposite all this mega-swag is a wall covered floor to ceiling with posters and lanyards from gigs Jarbo’s performed at and cons he’s attended, including a few from summer 2007, when the Mega Ran project blew up in popularity. And it came as a total surprise to Jarbo.

Jarbo had lost interest in hip-hop before relocating to the Valley to take a job teaching special education students at an elementary school in the Fowler Elementary School District in Phoenix. “Music became completely secondary in my mind after I’d done everything I’d wanted to do on The Call,” he says. “I kind of separated myself from music and pulled myself back into video games.”

He discovered emulators and binged on old-school classics, including anything Mega Man-related. Hearing the background music again reminded Jarbo of how much he adored the tunes and it sparked an idea. He began downloading MP3s from a fan site and started remixing them into hip-hop beats. The lyrics started popping in his head soon after.

“I slowed down the Woodman theme from Mega Man 2 and had this melody in my head going, ‘I just can’t seem to grow up’ over and over,” he says. “It just fit perfectly. And so that’s what got me writing words again.”

The result was the track “Grow Up,” which got enough positive feedback from friends and fellow rappers that Jarbo began making more Mega Man-inspired material on nights and weekend when he wasn’t teaching. It grew into the Mega Ran concept album, which he says was a joy to create.

Jarbo was big into the Nintendo Entertainment System growing up.

Jim Louvau

“I’d found something fun about music again,” Jarbo says. “After The Call, I just wanted to have fun. I didn’t want to make heavy, serious rap anymore and just wanted to rap about stuff I loved.”

In other words, the very ethos of nerdcore, the hip-hop subgenre featuring artists rapping about any and all things geeky. Damian Hess, who performs as nerdcore pioneer MC Frontalot, says it’s a loosely defined term covering a wide variety of subject matter.

“I like to think that it’s the intrinsic dorkiness of the artists themselves that generates the nerd elements in the songs,” Hess says. “Everyone that does [nerdcore] has some idea about why that word would describe their process. For some

In 2007, nerdcore was exploding in popularity. The music of such artists and rappers as YT Cracker, MC Lars, and mc

In other words, it was the perfect time for a project like Mega Ran. The album was certainly unique, as no one in nerdcore or hip-hop had centered an entire album around either video games or a specific series. “I was like, ‘Let me check the internet. Are you sure nobody’s ever done a whole rap album for a video game before? Really?” Jarbo says.

Even then, he had no idea if it would be successful. “No, I honestly thought this was just a side project,” he says. “I didn’t even want people to know it was me doing it at

He was full of doubt. He had just lost his teaching job in Phoenix because he failed to enroll in a required grad-school program. And he had little expectation of success for Mega Ran after posting it online in June 2007, especially after getting a lukewarm response on his MySpace. “I told all my friends, told my top eight, and not everybody was into it,” he says.

It got onto gaming fandom’s radar, however, and within weeks was getting thousands of plays per day and reviewed by prominent game site IGN.

Someone else noticed it, too: Capcom, the company behind the Mega Man franchise.

Jarbo thought it was game over after Capcom contacted him. “It felt like, ‘Well, it was fun while it lasted. Now I’m done,'” he says.

Thing was, Capcom dug the project. He got an invite to be their official guest at San Diego Comic-Con the following month. “And I’m like, ‘Uh, what?’ It was crazy. Definitely not what I expected,” he says. Nor was the exclusive licensing deal they offered him to rap about their character, the first of its kind.

The original Mega Ran album was so successful that Jarbo started calling himself “Random (a.k.a. Mega Ran).”

Capcom hit him up a year later to produce an album inspired by Mega Man 9, a retro-styled sequel that was available on Xbox Live and the PlayStation Network. They didn’t have to twist his arm, especially after he heard the background music for Splash Woman, the first female boss character in the series.

“I was absolutely hooked,” he says. “I thought, ‘This one will write itself since I can do it as a love story.'”

“Splash Woman” became one of Jarbo’s best-known creations and was even featured in episodes of Tosh.0 and Portlandia.

Then came Black Materia in 2011.

A concept album focusing on the phenomenally popular PlayStation title Final Fantasy VII, it featured 16 tracks, each told from the perspective of the game’s characters. It’s such a deep game and lore with so many memorable characters,” he says. “So when I decided to do it, I called up pretty much all my rapper friends who were also fans of Final Fantasy and asked them to rap on songs as a different character.”

Jarbo wrote and recorded Black Materia over the course of a year, transforming the closet of his apartment into a DIY recording studio.

“This is probably the record I took the longest to record because I wanted it to be right,” he says. “I didn’t want to just retell the story, like a lot of stuff I hear in nerd rap sometimes that’s straight from Wikipedia, like, ‘Here’s [the plot of] Game of Thrones in 16 bars.”

Jarbo’s hard work and attention to detail paid off. Huge. Immediately after its release, Black Materia made the front page of Reddit and held its own on the iTunes and Amazon charts against the likes of Kanye and Lil Wayne. It was an accomplishment for both Jarbo and nerd rap as a whole.

“And I was like, ‘Whoa, an album about Final Fantasy is right next to the biggest guys in rap,'” he says.

Jarbo’s fame increased exponentially. He was deluged with offers for gigs, speaking appearances, and collaborations. Black Materia‘s success not only fueled Jarbo’s fame, it also motivated him to quit his latest teaching job at now-defunct Valley charter school Omega Academy to focus full time on music.

“I starting thinking, ‘Music is my job now,'” he says. “And that’s what gave me the courage to quit.”

But he still wanted to teach others – with his music.

When times get tight you want to take flight / Gotta remember a blessings in sight / After the storm comes the sunlight / I smile really wide then I stand up right / ’Cause something tells me it will be alright. — Mega Ran, “Unspeakable”

It’s the middle of Jarbo’s busy day in July before he heads for Ohio to hang out with

The real people sweating, however, are the rappers who submitted tracks for a “free feature” contest tied to the release of Emerald Knights 2. At stake is the opportunity to have Jarbo and Gamarano write and record guest verses and hooks on an upcoming track by the winning artist.

As Jarbo watches on from a futon, Gamarano sits at a computer cueing up submissions. Some are decent; others are lacking. Each gets a listen, even if only for a few seconds before getting silenced, like one rapper trying to sound like Ludacris, circa 1999.

“Oh my, no,” Jarbo says.

“Yeah, I don’t think he’s making the cut,” Gamarano agrees.

Both rappers have been on the other end of this experience before. As such, the rejection emails they’re sending to the runners-up try to break the news gently while complimenting their rapping skills and encouraging them.

“Oh, yeah, I’ve gotten a lot of rejections before,” Jarbo says. “All the time, I send stuff out to people and get my heart broken.”

Jarbo has been big on doing solids for up-and-coming rappers whenever possible (hence the contest) for decades now. He’s already provided guidance to several prominent nerdcore artists, including rapper Sammus. In a 2015 interview with hip-hop site Scratched Vinyl, she describes Jarbo as “such a good mentor” who showed her the ropes of the rap game.

“When he’d do something, he’d be like, ‘This is what I did, and this is why.’ So I was able to figure out for my own purposes – and I think that’s really dope,” Sammus says. “I know there can be a lot of

She isn’t alone. Hess says that Jarbo provides a positive example for would-be nerdcore artists looking to follow in his footsteps.

Jarbo mixed hip-hop and video games to create his own style.

Andrew Doench

“Every nerd rapper I know looks up to him,” Hess says. “[He’s] an inspiration to people who are nerd kids who would like to make music and have people hear and appreciate.”

Jarbo’s influence isn’t limited to just performers or nerdcore noobs. He gets dozens of emails and Facebook messages each month thanking him for being an inspiration in their quest of pursuing their dreams (one person even cited his music as the soundtrack to their training montage).

And when not providing a positive influence, he’s just flat-out being positive.

“There’s enough negativity in the world. I’ve never been about that,” Jarbo says. “I came up in Philadelphia where there was a lot of negativity, maybe not at the level we see in geekdom today, but just a different sort of negativity, more face-to-face and street aggressiveness and I tried to always stay away from that. I’ll be the corny, positive, cheeky person who is smiling on the side because I’m just happy to be here.”

You’ll also never hear him curse or get into

With the exception of slamming egotistical game show hosts, Jarbo stays away from hip-hop drama. “They’re ego plays that aren’t worth wasting the energy,” he says.

He’s got a few things to say about the rash of toxicity and bullying that’s afflicted geekdom in recent years, like the backlash against The Last Jedi or the all-female Ghostbusters flick.

“We see so much of that in geekdom, treating people differently because of what they look like or are into games and it really is disgusting. Toxic is a good term for it. We’re seeing it now with Star Wars and other stories where people of color or those of other genders are getting [harassed] online for playing different characters. It’s really disgusting,” he says. “I actually just finished a verse all about that, I talk about how that’s an issue we need to fix because we [geeks] were the bullied and now we’re becoming the bullies. … People just need to shut up and enjoy the art.”

Jarbo freely admits it’s sometimes been difficult to maintain his attitude.

“It’s been more of a challenge being the rapper who’s positive, the rapper who didn’t curse, the rapper who’s the opposite,” he says. “So it’s harder to be yourself in spite of the world around you than it is to do what the world is doing and fit in, but I just want to be the rapper who’s telling stories and spreading music with a message.”

In recent years, however, the stories Jarbo’s been telling, particularly in Emerald Knights 2 and other recent projects, have been less about games or other geeky subjects.

So does that mean he’s pulling the plug on his video game and geek raps that made him famous?

But you only live once, well imma disagree / Cause you can live forever and forever doesn’t cease / Live through your creations and the people that you teach / So I live through my music, eternally through the beats. — Mega Ran, “Infinite Lives”

It’s T-minus eight hours until Jarbo jets off across the country to the Gathering of the Juggalos, and he’s just wrapped up the latest taping of Mat Mania with fellow rapper

And after an hour of frankly discussing whether Hulk Hogan should’ve been reinstated to WWE’s Hall of Fame (definitely not, says Jarbo) and other current events in wrestling, he’s being just as blunt about the future of his career.

When asked if the content and themes on albums like Emerald Knights 2 or Extra Credit indicate he’s moving away from purely video game material or nerdcore, Jarbo says it might.

“There are tracks I do for Patreon subscribers that are specifically video game-centric, but for album stuff,” he says. “I’d rather make

Besides, Jarbo says, there’s little difference between nerd rap and regular rap.

“I just don’t think there’s a huge distinction

If you look at Jarbo’s last few albums, he’s been moving in this direction for

Jarbo (left) and Michael Gamarano, a.k.a. Bag of Tricks Cat.

Luis Perez

The transition is most pronounced on Emerald Knights 2, which features the occasional geek reference being used as metaphors. On “If I Could,” for instance, he compares first responders and teachers to being superheroes.

Emerald Knights 2 represents Jarbo’s most diverse and mature work as a hip-hop storyteller, covering a wide variety of themes about his life and not just his hobbies or pursuits.

“I do usually operate under concepts, and as fun as that can be, it can get a little restricting,” Jarbo told Bandcamp Daily earlier this year. “For example, if I’m talking about Mega Man, I have to frame everything around that character, and what that character would go through. This album gave me a much wider palette because the focus was just [me and Bag of Tricks Cat], our everyday lives and our everyday feelings and emotions being musicians who travel, work hard, and make music.”

It’s also worth mentioning that RNDM and Emerald Knights 2 both hit Billboard‘s Heatseekers charts the week of their respective releases and are Jarbo’s only albums to do so.

So does that mean Jarbo is moving away from gaming-oriented raps for broader subject matter?

We ask him about it a week later. Thankfully, he has no intention of pulling the plug on that.

“I’ll never get tired of games or rapping about games,” he admits.

Still, he fears being pigeonholed as just a video game

“I do feel like I kinda painted myself into a corner.

Growing older and what sort of legacy he’d like to leave when he taps out of rap are two issues he’s been grappling with lately.

In the lo-fi and intentionally goofy music video for “Old Enough,” Mega Ran is considering quitting before a visit from a time cop from the future. She takes him on a journey through time – in a DeLorean, no less – to revisit his career (think It’s A Wonderful Life meets Back to the Future). Hence the reason why he’ll strive for balance in his music.

“I’ll try to. It’s purposeful. I try not to do one thing or another. I try to maintain a balance for myself, not for any listener. People need to know I’m

He’s down to rap about anything these days, even if it’s not games.

“It’s taken a long time, almost 10 years, to get to where now I’m fully comfortable with everything I do. I could talk about my spirituality, I could talk about politics, I could talk about video games, I could talk about comic books, wrestling, everything that I want, all on the same album,” Jarbo says.

He’s already making plans for his post-performance career, including conducting hip-hop workshops, supervising music projects, or showing artists how to survive the rap game. In the meantime, he’s not stopping anytime soon.

“I’m 40 now and feel like I’m still good at it, no one’s told me I suck, and I haven’t been too fatigued to play shows, or whatever. Until that day comes, I don’t know,” Jarbo says. “I’m just trying to say everything I can before it’s game over.”

He’s reminded of one of the first games he played on his Atari 2600.

“I feel like I’m Pac-Man eating all the dots before the ghosts catch me. And in this case, the ghosts are old age or falling off, those things that happen to every artist eventually,” Jarbo says, adding later, “at the moment, though, I feel like I’m about to grab a power pellet and really start rolling.”

Mega Ran is scheduled to appear at Game On Expo 2018 from Friday, August 10, to Sunday, August 12, at the Phoenix Convention Center. He’s also scheduled to perform on Friday at Last Exit Live.