Sahara Sajjadi

Audio By Carbonatix

Jamil Shahin remembers the flowers.

It was 2017, and Shahin and his family had just landed at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport after a long flight from Istanbul. Their exile from home had lasted much longer.

Five years earlier, Shahin had shepherded his family out of their native Syria as the country was engulfed in violent conflict between rebel groups and brutal dictator Bashar al-Assad. They’d fashioned a life across the border in Turkey, where Shahin helped open a community center and medical clinic. A half-decade in, the United Nations called, offering Shahin and his wife, three children and brother refugee status in the United States.

That brought them all to Arizona and to the flowers. Shahin saw them in the hands of a family awaiting someone’s arrival at Sky Harbor. He comforted his distraught wife with a vision of the future. “Don’t cry,” he told her. “One day, we will go back to Syria, and our family will be waiting for us with flowers.”

To Shahin’s surprise, the family that the welcome party awaited – with flowers and halal food – was his.

It was an auspicious moment, auguring just how much Arizona would become home for the Shahins and other Syrian émigrés like them. Shahin is now the president of the Syrian Community Service Center in Arizona, which serves the 2,251 Syrian refugees who relocated to Arizona. Though their mere presence was often political, they have forged lives away from their beloved and war-torn homeland, starting businesses, building families and putting down roots.

Now, after the stunning overthrow of Assad by rebel forces last month, they face a decision they hoped to someday confront: whether or not to return.

Shahin longs to go back. “I want to visit my country,” he said. “I am homesick.” Many Syrian refugees in Arizona ache to do the same, to reconnect with family and rejoice in their country’s liberation. But a funny thing happened since they left, many told Phoenix New Times in interviews. Forced to flee, they’ve crafted new lives, exemplifying the kind of immigrant success story America loves to tell about itself.

Syria is their homeland and will always be. But Arizona is now home.

Jamil Shahin waves the flag of the Syrian opposition in front of the White House in 2019.

Courtesy of Jamil Shahin

Leaving home

Starting over, of course, was anything but easy. The mere act of leaving Syria was agonizing.

When the pro-democracy protests known as the Arab Spring erupted across the Middle East in 2010, there had been so much hope. The movement toppled dictators in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya before lighting a spark in Syria in 2011. There, however, it ground to a halt.

When the uprising first began in Syria, Shahin joined demonstrations against the Assad regime, which had held the country in an iron grip for 50 years. But Assad was not deposed so easily and visited his vengeance upon his people. Dissidents began disappearing and turning up dead. One day, regime forces showed up at Shahin’s door with a warning: a picture of Shahin at the protests.

Shahin fled with his family to Turkey as quickly as he could.

For many Syrian refugees, it was a heartbreaking exodus. Whatever safety they’d achieved was tainted by the knowledge that their families back home still faced incredible danger.

“It was very hard to leave my country, friends, family,” said Basmah Al-Zoubani, who fled Syria in 2015 and now lives in Tempe. But amid a bloody civil war – which many refugees regarded as a revolution against Assad – she knew she had no choice but to escape.

Arizona State University student Zaki Amish was just 9 years old when war overtook Syria. He mostly remembers the sounds – of protests, nearby gunshots and the screams of his baby sister. The firefights outside his home were so chaotic that his family snuck out through back alleyways to avoid being caught in the crossfire. Eventually, the family fled Syria by bus to neighboring Jordan.

In 2012, when regime forces began deploying barrel bombs on Syrian neighborhoods, Rabah Al-Hariri escaped to Jordan with her husband and children. After leaving, she learned that the regime had shot and killed her brother, a fighter in the Free Syrian Army. She still struggles to talk about it.

Shahin has lost two brothers since leaving. While Shahin was in Turkey, he learned that his brother Nabil had been shot and killed for his political activities. Regime forces dropped Nabil’s body at his mother’s doorstep, sending her into a state of shock. In 2013, Shahin learned that his older brother, Basem, had been locked up at the notorious Sednaya prison, known to Syrians as a “human slaughterhouse” where anti-Assad dissidents were tortured, raped, starved and forced into false confessions.

That was the last Shahin heard of Basem until a month ago, when Assad fled to Russia and the prisons were liberated. Shahin frantically watched social media videos of the prisons, searching for a sign of Basem. He got his answer, but not the one for which he’d prayed. In 2014, Shahin learned, Basem had been tortured to death.

Many refugees found safe harbor in nearby countries. Resettlement to the U.S. was a possibility, but Al-Hariri wondered if that would be worth it. In Jordan, at least they were close to home and living in an Arabic-speaking country. America offered a language they did not speak and no family members.

But it also promised opportunity. When offered refugee status in the United States, Al-Hariri ultimately thought of one thing: her children’s future. So the Al-Hariris and many other Syrians did something almost as scary as leaving home. They boarded a flight, touched down in Phoenix and completely started over.

Basmah Al-Zoubani chats with a Syrian customer while selling baklava at the Downtown Phoenix Farmers Market.

Sahara Sajjadi

A new life in Arizona

When Shahin arrived in Phoenix, he had only $300 in his pocket. He worked at a restaurant to make ends meet, saving money to purchase a car. Once he’d pulled together $2,000, he bought a 2007 Honda CR-V and started driving for Lyft.

He aspired to more than ferrying others around his new hometown. Arizona had no community center for Syrians, so Shahin set out to create one. With a tax refund, he rented a small office space to house the Syrian Community Service Center. Shahin would sift through trash bins for discarded office supplies to keep the new community center afloat. Through WhatsApp, Shahin invited fellow Syrians to drop in – to get help with translation or schooling or just to get a taste of home.

Eventually the rent became more than Shahin could afford. But the community center lives on, meeting in public parks or on the ASU campus. The Syrian Community Service Center is now partnered with ASU and offers the American Dream Academy, a five-week course in which families learn more about applying for college and scholarships, different majors offered and other opportunities. In 2022, ASU President Michael Crow awarded the program the Advancing Families Through Learning and Doing award, citing its forward-thinking approach.

Shahin is not the only migrant to have preserved a slice of home in Arizona.

A baker in Syria for more than a decade, Al-Zoubani founded Al-Zoubani Sweets and sells traditional Syrian treats to Arizona residents. Khaled Al-Rabai, who fled Syria in 2012 and spent four years in Jordan before coming to America, also turned to food. He and his wife run Rodain’s Syrian Kitchen, bringing Middle Eastern cuisine to the Valley.

Both Al-Zoubani and Al-Rabai received help from the International Rescue Committee to start their businesses. The IRC helped Al-Zoubani acquire a food license and stood alongside her offering translation for potential customers. It assisted Al-Rabai and his wife, Rodain Abo Zeed, with training to establish a bakery as well as a $10,000 loan to launch a catering business.

These stepping stones helped the business owners stay close to their Syrian roots and chase their dreams in a new country. Today Rodain’s Syrian Kitchen has a weekly spot at the Downtown Phoenix Farmers Market where it offers falafel, Turkish coffee and chicken shawarma. Al-Zoubani Sweets, a few tables away, sells baklava and other homemade Syrian confections.

When Amish first arrived in Arizona, he asked a stranger for the time and realized he could not understand the answer. He busied himself with his schoolwork to learn English – for his own sake and for his family’s survival. Soon, Amish was able to serve as a translator for his parents. Today he is on track to graduate from ASU with a degree in biomedical engineering.

Al-Hariri said she and her family also struggled for a year to adjust to life in Arizona before finding her niche doing henna art. Provided with tools and rental aid from the IRC, she now considers her business, Henna By Rabah, a great success. It has kept her family afloat and kept her emotionally connected to home. Her youngest daughter, 11-year-old Jood, is following in her mother’s footsteps, papering their refrigerator with her own henna paintings.

Jood was born a year after her mother fled Syria. She has never known the Middle Eastern country. Now that Assad is gone, she finally will. The Al-Hariris will visit Syria next summer, reuniting with family they haven’t seen in more than a decade.

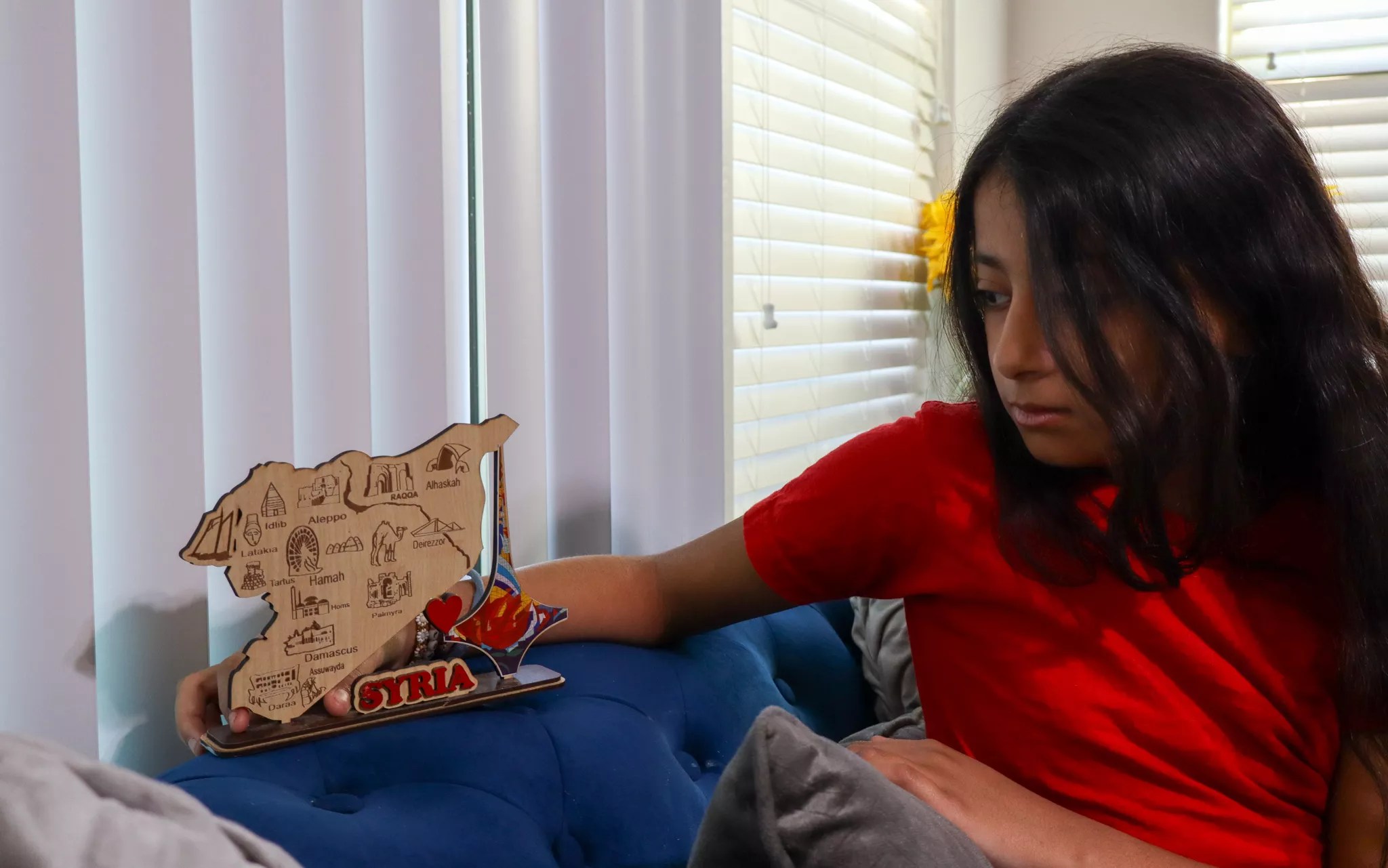

Jood Al-Hariri, 11, looks at a map of Syria at her home in Mesa.

Sahara Sajjadi

To stay or to go?

Shahin is eager to return to Syria. He has nieces and nephews he has never met. Money is an obstacle, but once he has saved up, he said, “I will go immediately.”

Shahin considers himself an American now. He is a naturalized citizen, a homeowner and an asset to his community. He feels a responsibility to Syrians in Arizona. Al-Zoubani and Al-Rabai feel the same. While they are thrilled to visit a liberated Syria, they have businesses, homes and children who are in school in the Valley.

Amish was too young to remember much of Syria before the war. He’s excited to return and rediscover the country he had to leave too soon. “Finally, I have a country to go back to,” he said. “There is hope. There’s a shot in the dark that we can go and visit the family we haven’t seen in forever.”

Many are thrilled to visit a liberated Syria. Others plan a more permanent return. Al-Hariri’s eldest daughter, Kheloud, has designs on repatriation. She came to the United States as a teen, starting her American schooling as a freshman at Glendale High School. After initially taking only English Language Learner classes and math, she caught up to her classmates and managed to graduate on time. She’s now on track to graduate with her associate’s degree from Phoenix College, after which she’ll pursue pharmacy school.

For Kheloud, there is no question as to whether or not she will return. She will. Her homeland is now free, but there is still so much it needs.

“I want to go back to Syria, my country. I want to help it,” she said. “We’ve missed it a lot.”