Hannah Critchfield

Audio By Carbonatix

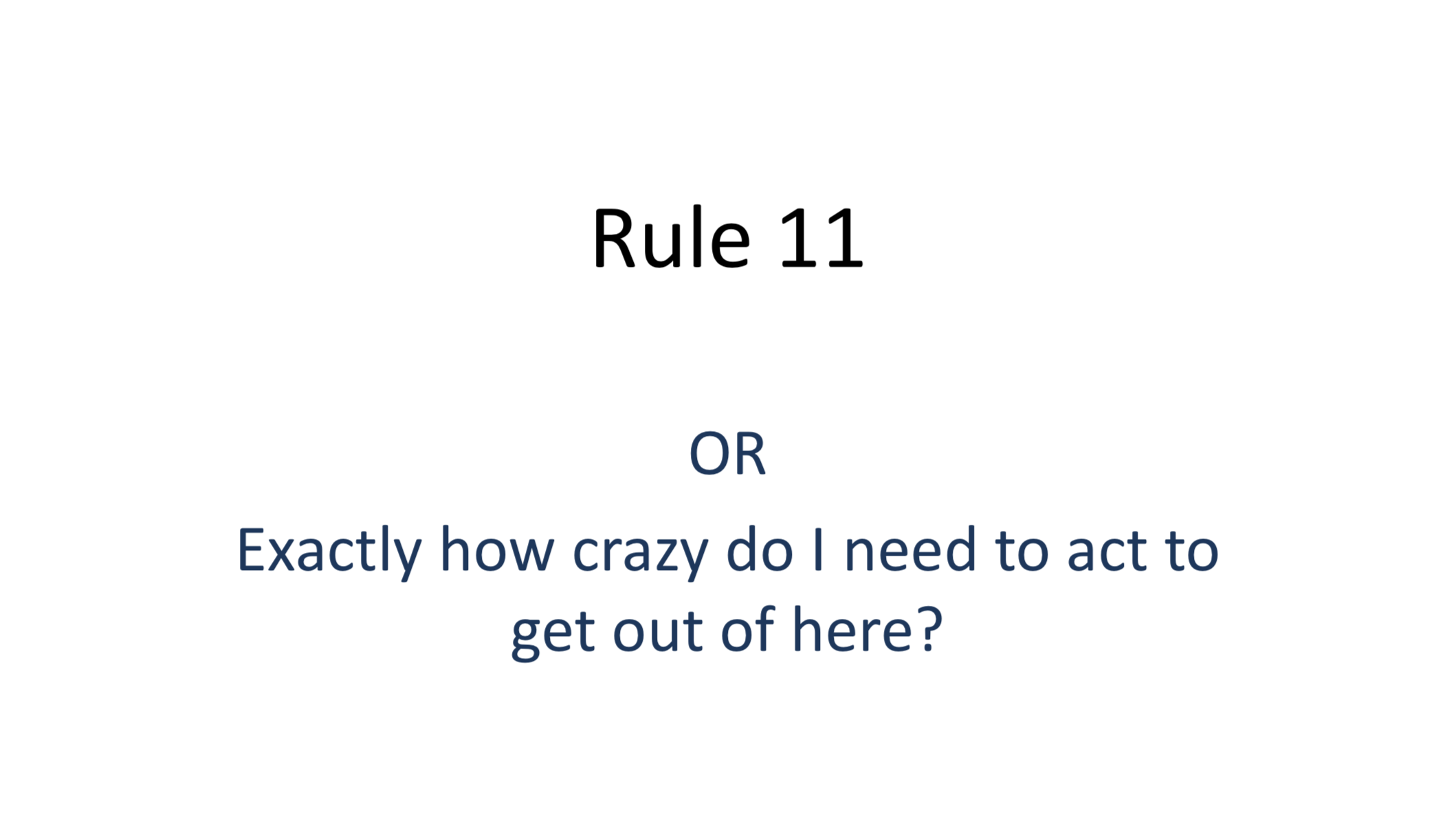

“How crazy do I need to act to get out of here?” says one Maricopa County Attorney’s Office mental health training presentation slide.

“Mental Health: Look at me, I’m CRAZY!” another reads.

So begin two official MCAO training materials on dealing with individuals with mental health in the criminal justice system, according to documents provided to Phoenix New Times by the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona.

The presentations are on mental health in homicide cases and Rule 11, the name for a court-ordered evaluation designed to determine if a defendant is mentally sound enough to understand court proceedings, and whether they understand the charges against them. The documents were obtained by the ACLU last Friday in response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed in October 2018. MCAO’s delay in providing these materials has been the subject of an ongoing lawsuit.

The official mental health training sessions, which include two PowerPoint presentations in a slew of other documents and data the county attorney’s office has begun to provide the organization, help paint a picture of how Maricopa County prosecutors are trained to engage and approach individuals experiencing mental illness in their courtroom. Advocates worry that the language used may bias prosecutors against the mentally ill, criminalizing mental health concerns, and preventing them from enacting a fair and balanced justice system.

“If you start out by dehumanizing the people that you’re prosecuting, or the mental health issues that they’re dealing with – in some cases it may not make a difference,” said Jared Keenan, criminal justice attorney at ACLU Arizona and a former public defender who dealt with many mentally ill clients. “But at some point, you have to be concerned that if your prosecutors are not looking at the people they’re prosecuting as an individual worthy of respect, it’s going to be a lot easier to throw them in prison, or to not care that they’re sitting in jail and not getting the mental health treatment they need.”

Amanda Steele, spokesperson for MCAO, said in an emailed statement that the agency deals with hundreds of criminal cases each year in which someone’s mental state is at issue.

“MCAO prosecutors approach each of these claims with professionalism and empathy,” Steele said. “Most claims of incompetency are made with sincerity. Unfortunately, some defendants make false claims of incompetency and malinger as a tactical measure to avoid responsibility for their criminal conduct. The purpose of MCAO’s mental health training for prosecutors is to aid our prosecutors in discerning legitimate claims from false ones.”

After reviewing the slides upon their release to the ACLU, Chief Deputy Rachel Mitchell, the current acting County Attorney, spoke to members of senior staff about the need to ensure trainings are created and conducted responsibly and with respect, Steele said. Mitchell also asked that the quotes in the two mental health trainings be removed, as they are “inappropriate, and without context can create a false impression that the Office is dismissive to mental health concerns.”

Last October, ACLU Arizona partnered with an investigative journalist to file a public information request for materials on how the top prosecutors in the state were conducting court proceedings. Though other attorney’s offices in Yavapai and Pima counties began to provide the requested information within months, the MCAO, then overseen by Bill Montgomery, never responded. After nine months of silence, the ACLU filed a lawsuit against Montgomery and the office.

The agency then began to fulfill the request, which asked for over 200 items related to mental health, restorative justice training (the office has none), LGBTQ sensitivity (the only document is the city’s general anti-discrimination law, required policy for all county agencies), and anti-bias training, sending ACLU Arizona documents on a rolling basis.

The two PowerPoints on Rule 11 and mental health, provided to the ACLU with little context on September 20, were some of the few requested training items that the MCAO has released without dispute – around 38 more related documents have been denied as “privileged information.”

Keenan of the ACLU Arizona said the majority of the contents within the two mental health trainings are comparatively innocuous.

“Once you get into the meat of the training, it’s a bit less problematic. It’s clear from the training that this comes from a prosecutor’s office, but I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s any more slanted than what a defense training on Rule 11 would say. And that I don’t think that’s problematic. Prosecutors have a different job than other players in the system,” Keenan said. “But everything’s sort of tainted by that first slide.

“Broadly speaking, prosecutors are supposed to do justice, and not just seek convictions. They’re supposed to evaluate evidence as neutrally and objectively as they can,” he continued. “If you start out either joking about these people or, or implying that all these people are faking – it’s telling of how prosecutors go after them.”

When someone who is charged by the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office seems unable to understand court proceedings, judges, prosecutors, or defendant attorneys may ask they undergo a Rule 11 hearing to evaluate their competency. If the person is deemed incompetent, their court proceedings must be suspended until they are restored to competency. This “Restoration to Competency” treatment is administered almost exclusively in jail, not a hospital, and is highly specific – it’s not meant to treat long-term mental illness, but solely designed to bring someone to the point where they understand allegations presented against them in court. It’s not an insanity plea – a lack of competency cannot be used as a defense in a trial; rather, it temporarily suspends court appearances, as the Constitution forbids local governments from prosecuting anyone unable to understand what’s happening around them.

Steele, spokesperson for the Attorney’s Office, said context is important when reviewing these slides.

“The trainings were created to ensure that prosecutors understood the legal process involved in Rule 11, and the first slides included a quote to address the difference between claims that may be seen as malingering and the importance of providing a defendant with proper assessments when there are mental health concerns,” Steele said.

Opening slide of another MCAO presentation on Rule 11 cases, provided to New Times by ACLU Arizona.

Hannah Critchfield

Before giving the presentation slides to New Times, ACLU Arizona consulted with its community partners at Puente Human Rights Movement, citing its work with many individuals experiencing mental illness who are currently facing charges through MCAO, including Valentina Gloria, a 19-year-old with severe mental illness facing several charges for spitting on an officer during a mental health episode.

“When I first saw the slides, I thought about every time I’ve been in court with Valentina and all the other people who are waiting in Rule 11 proceedings, and just felt completely disgusted by what I saw,” said María Castro, community organizer for Puente. “All of those people who we see in court are being judged by these prosecutors … The heavy bias that these people are carrying when they’re prosecuting is not giving our loved ones who are behind bars a fair chance.”

Dr. Gary Freitas, a retired psychologist who formerly worked with Rule 11 inmates in Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office’s Restoration to Competency program, also reviewed the documents at New Times’ request.

“Having testified on both sides of these cases, I understand the prosecution mindset that the not-competent-to-stand-trial defense can often be fraught with acts of malingering – it would have been better to withhold the skepticism and trust the process,” Freitas said. “The appearance of objectivity in this matter is important, as is the recognition that many seriously mentally ill people are arrested and being held in custody awaiting trial. It’s the dark humor that both sides express towards the one another – probably best to not put it in a slide.”