Joseph Flaherty

Audio By Carbonatix

I drove to the military base as “Mr. Blue Sky” played on the car stereo. Ordinarily, the song felt upbeat: Sun is shining in the sky / There ain’t a cloud in sight. But because of the context of my trip, the lyrics were unsettling. All I could think about was a nuclear missile dropping out of the blue Arizona sky.

It’s stopped raining, everybody’s in the lane / And don’t you know, it’s a beautiful new day.

The week before, I’d watched a geopolitical back-and-forth that flirted in a shockingly casual way with nuclear annihilation. Threats of “fire and fury” and an imminent plan to strike the waters of Guam had done the impossible, overloading my general anxiety to leave me numb, unable to comprehend if what I was witnessing was real. Was this how it all ends: madman theory playing out in reality, with the entire world held hostage?

Of course, it wasn’t the end. But if missiles were in the air – North Korea just launched a trio the other day – and Phoenix was on the shortlist for nuclear annihilation, you could only hope to be inside the Maricopa County Emergency Management Office: a Cold War-era fallout shelter.

“Welcome to the dungeon,” an assistant told me with a grin as we walked down a flight of stairs, headed underneath the mountain.

Robert Rowley, the director of emergency management for the county, noted, “Whoever decided this as a location back in the ’50s picked a really good spot.”

A former deputy sheriff of Monterey, California, Rowley wore glasses and a crisp button-down shirt. He ticked off a dizzying list of the fallout shelter’s advantages: “We’re on high ground. We’re away from downtown. We’re on a secure facility. We’re underground. We’re on a generator. We have our water, so we can survive off utilities. We have satellite Internet.”

Robert Rowley, director of emergency management for Maricopa County, in the shelter’s emergency operations center.

Joseph Flaherty

Needless to say, the facility was built to survive the bomb. A relic from the days of Eisenhower and Kennedy, the bunker was built in 1956, and still has a slightly eerie Cold War aesthetic to the narrow hallways and beige paint on the walls. It’s also an impressive site: It’s cut into red sandstone into a hill on Papago Park Military Reservation. On the day I visited, National Guardsmen checked my I.D. at a barricade and strolled purposefully around the base.

During the Cold War, the Office of Civil Defense assumed many of the responsibilities of its predecessor agency that marshaled resolve and resources during World War II. However, in a new twist for the atomic age, Civil Defense educational materials and supplies were meant to educate the public on nuclear attack on American soil from the Soviet Union.

The fallout shelter still has old Civil Defense supplies: a pair of Geiger counters, an information pamphlet, and cans of water, all with the C.D. logo. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed, the practices of Civil Defense had transformed into modern-day emergency management, more attuned to dealing with floods and hurricanes than ICBMs and fallout borne on a mushroom cloud.

Geiger counters feature the Civil Defense logo.

Joseph Flaherty

The flight of stairs where I entered the building is not the original entrance to the shelter. For that, Rowley led me through the narrow hallway, passing by what used to be dormitories for the personnel stationed here, until we reached a huge iron door, accessible from the roof at the top of the red-rock hill.

Three latches crossed the door’s inside, but its exterior was smooth: There is no door handle or knob, designed to withstand a barrage of radiation and debris.

Once it slammed shut? “You’d have to make it in before the blast door closed,” Rowley said. Running down the avenue / See how the sun shines brightly.

The idea, he explained, was that any surviving government officials would enter through this blast door, but once inside the facility, they would have shower off any radioactive dust that had collected on them before entering the shelter.

We walked through what was the “Decon Corridor,” hemmed in by a wall of red rock – underground, you’re constantly reminded that the shelter is squeezed inside a mountain – before we got to the tiled room where officials would get rid of any fallout on them. Now, it’s an ordinary restroom.

On top of the roof, they have a 20,000-gallon tank of water and radio antennae. A gigantic red sandstone rock is perched on top, surrounded by a couple cactuses.

In the 1950s, excavators worked to move all the rock out from this side of the mountain, filled the innards with concrete, and then covered it again. Rowley pointed out a square concrete slab where an antenna was tethered. A few names – Herbert, Bill, and Ray – were carved into it. Probably construction workers, they left their marks there sometime in the ’50s, but Rowley didn’t know when. The last number in the year had been worn away, leaving just “195.”

The rooftop of the center for emergency management.

Joseph Flaherty

Of the hilltop location, Rowley said, “We have the million-dollar view that we never get to see because we’re underground.”

Maricopa County has considered moving the emergency management office to a new location, he explained. But “survivability” makes it hard to justify a change in location – even if it means giving up a modern office with amenities like wider hallways, not to mention sunlight.

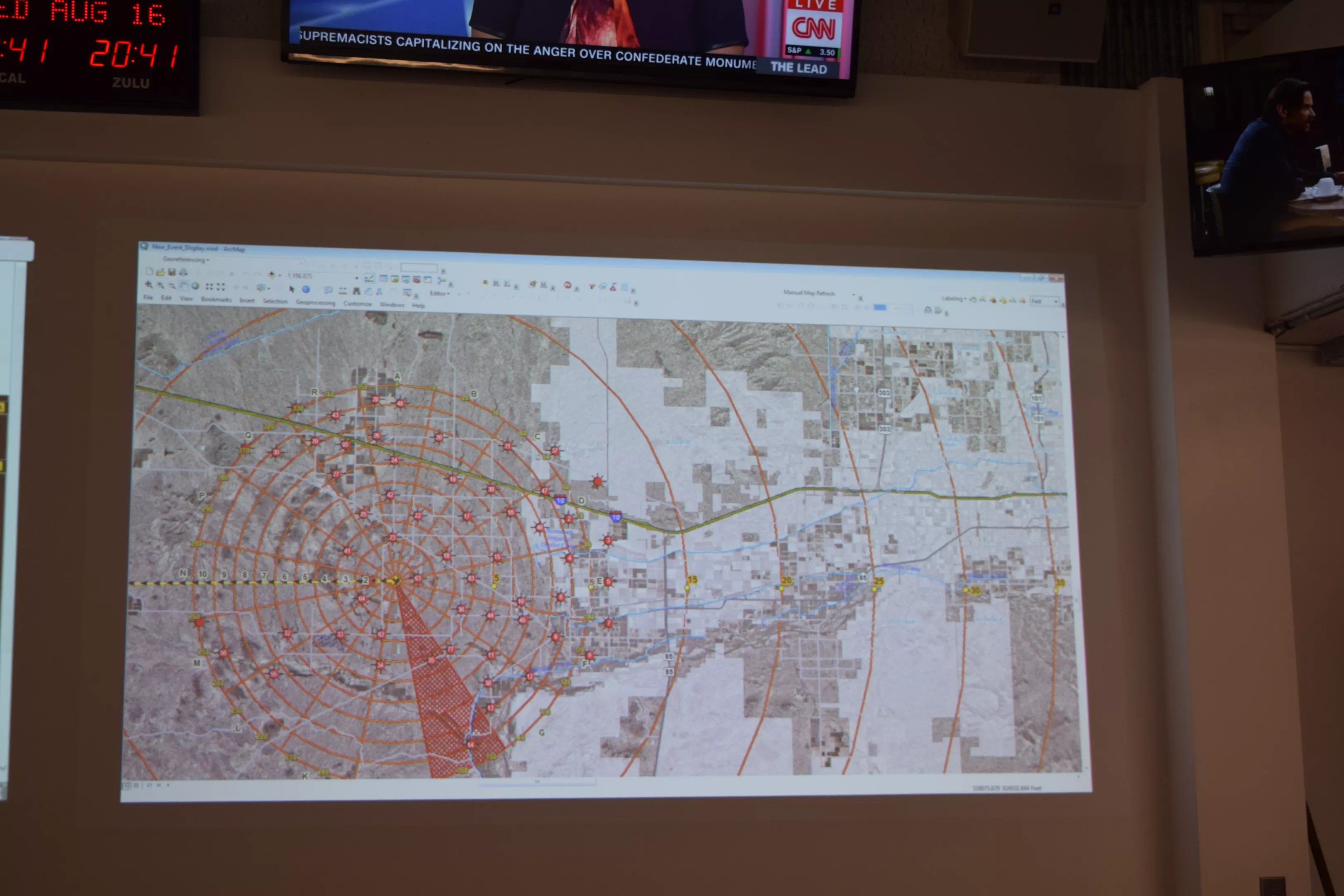

One modern part of the office is the emergency operations center, a two-tiered room with computer, projection screens, and a digital clock with bright-red numbers on the wall. One screen displayed a map of the region, with nearby Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station represented as a yellow-and-black dot.

Concentric circles around the plant were used to plan an evacuation, should the nuclear site experience a radiation leak or other emergency. Because of the nuclear plant, federal regulators require the county to maintain evacuation plans and records of the population that lives in various zones around Palo Verde.

“Maricopa County has an advantage in that we do a lot of radiological planning here,” Rowley said. “So we have an above-average knowledge of what the aftermath is of a radiological event.”

A map on the wall of the emergency operations center shows the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, located about 50 miles west of Phoenix.

Joseph Flaherty

The job of an emergency manager isn’t easy. Not wanting to provoke alarm, they gently remind residents of the basics which can save lives in any emergency, atomic or otherwise: Make a family communication plan or meeting point in the event of a natural disaster. Keep a battery-powered radio at home. Don’t forget to have a “go-bag” ready in case you need to evacuate in a hurry. But that doesn’t mean people heed the advice.

“Our natural psychological makeup is to stay in the lanes of normalcy and routine,” Rowley said. “And even after an event occurs, you’ve got a small window of time to get people’s attention to do something. They may do it then. And then six months later, it’s time to change the water, and you don’t do it; the food’s expired; the clothes in the go-bag don’t fit anymore.”

Cold War-era Civil Defense was designed to prepare the public for a possible nuclear strike.

Joseph Flaherty

The bunker at Papago Park is not meant to be a public shelter. And public fallout shelters the way Civil Defense planners conceived of them, with a triangular sign marking their location, don’t really exist anymore. While there’s no list in Maricopa County, most have probably been repurposed into storage rooms and basements. The county has a list of designed shelters for natural disasters, but only makes them known when an emergency is imminent.

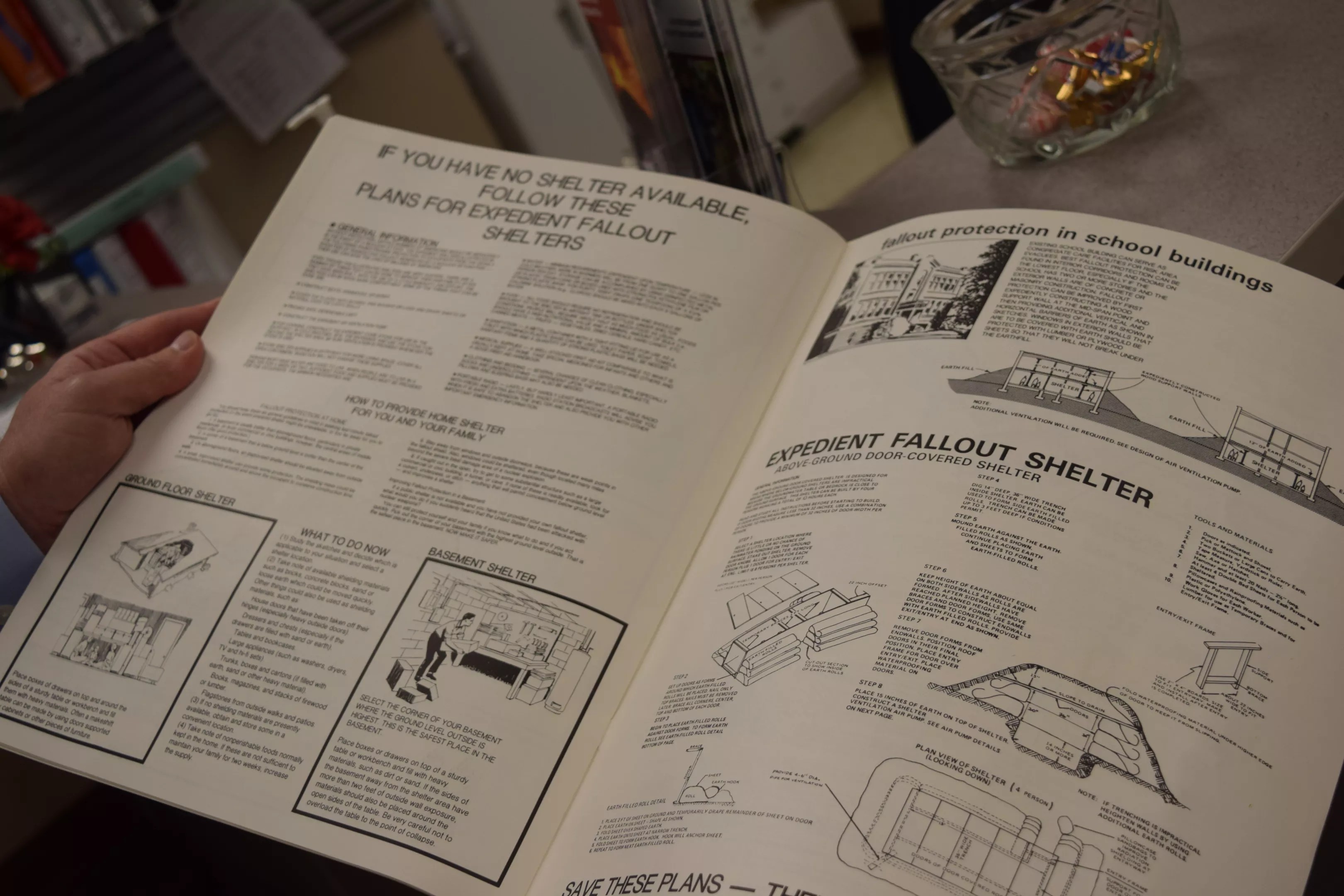

Before I left, assistant Stephanie Miller pulled out an old booklet with the Civil Defense logo of Maricopa County emblazoned on it. Unlike those grainy duck-and-cover videos shown to schoolchildren, this information was not funny in the slightest.

The cover page described a scenario where all diplomatic efforts have failed, and a nuclear attack on Phoenix and its environs is imminent. “SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS,” the last sentence screamed in all-caps. “THEY MAY SAVE YOUR LIFE.”

A copy of a Civil Defense booklet that shows how to construct a makeshift shelter, among other atomic bomb survival tips.

Joseph Flaherty

Diagrams showed how to build your own makeshift fallout shelter. A family crouched under a pile of household goods in a kitchen, a terrifying version of the blanket forts built by kids. A car parked over a ditch could serve as an effective radiation shield, I learned, for those people unlucky enough to be on the road during the apocalypse.

The document read like an alternate history of the Cold War. It was like peering into the universe where the Cold War never ended, and the U.S. and Russia careened into mutually assured destruction.

Never mind, I’ll remember you this / I’ll remember you this way.