The persecution of the Rohingya has been described by no less of an authority than the United Nations as a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing." But little has been done since violence broke out in late August, leading to the death of hundreds of people and prompting thousands of others to flee the country. Here in Phoenix, Rohingya refugees are wondering why no one seems to be paying attention.

Among those trying to spread awareness about the crisis is Sheraz Islam, whose own father died less than a month ago while trying to flee the country for Bangladesh. His family lost their home, their land, and everything they own, he says. And convincing Americans to care, when they may or may not even be able to point to Myanmar on a map, is a challenge.

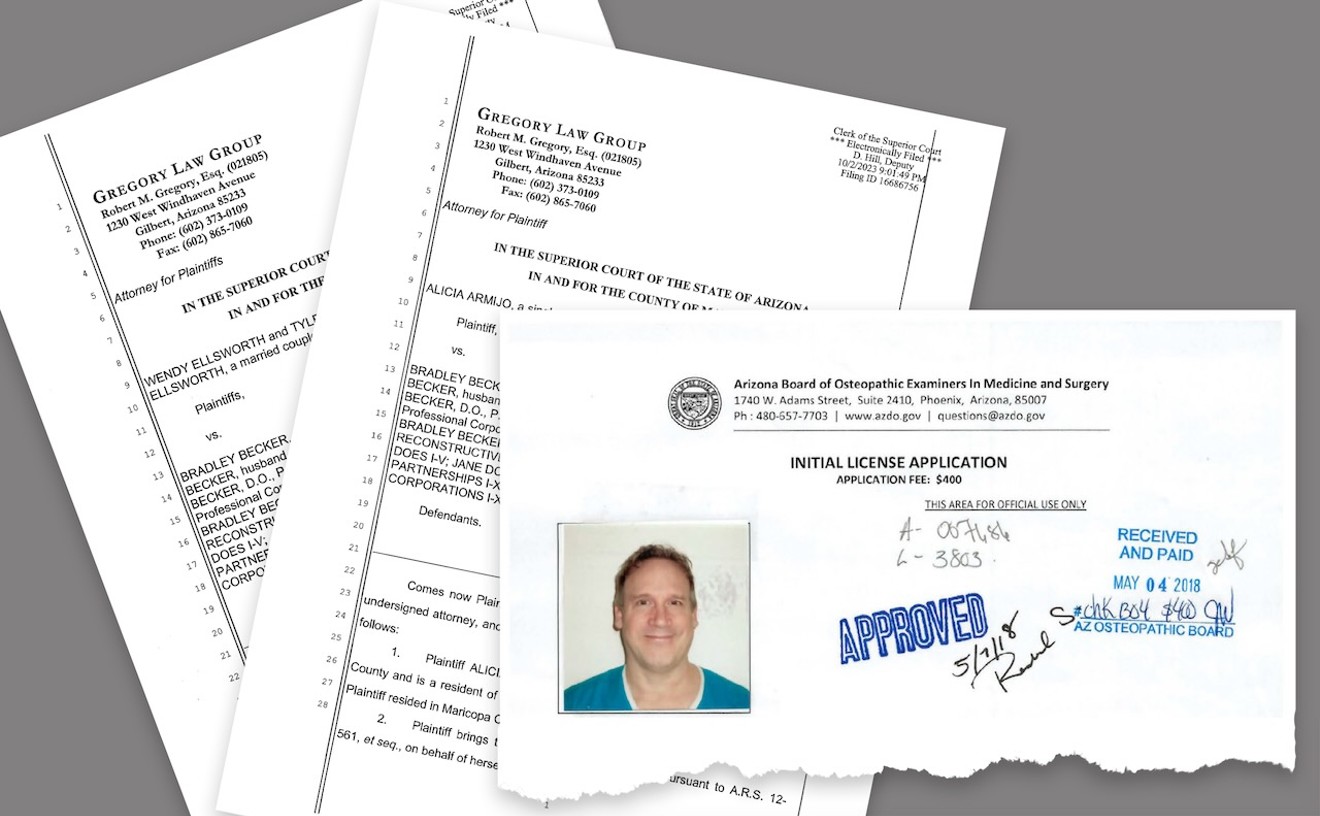

Rohingya refugees and Muslim community leaders gathered on ASU's Old Main Lawn on Sunday.

Antonia Farzan

"We’d like to live in our own country, but unfortunately we had to leave because we are Rohingya."

Islam is one of roughly 600 Rohingya refugees currently living in the Valley. They make up less than a quarter of the total number of Burmese refugees who have been resettled in Arizona since 2001. Most are Muslims, and arrived after 2012, when attacks on the Rohingya intensified after decades of discrimination.

If you hadn't noticed there was a Rohingya community here, that's because everyone's busy working so that they can send money to their families, Islam says. He himself has 10 siblings who live with his mother in a makeshift refugee camp in Bangladesh, and he sends them most of his wages from his job at an international grocery store.

On top of that, he says, "I have to take care of myself, too. It’s not easy to survive and to pay rent."

Most Rohingya refugees are in the same position, he says. "We have a lot of people who are working very hard, in many different jobs. To make a community, it's not easy — we need financial help. With empty pockets, we cannot become a community."

Islam fled Myanmar alone at the age of 17. His brother had been arrested and sent to prison for 20 years — for no reason besides the fact that he was Rohingya, Islam says. He decided it was time to leave.

After landing in a refugee camp in Sri Lanka, he applied for asylum through the United Nations. The U.S. State Department approved his application, and, a little less than six years ago, he arrived in Arizona. Lutheran Social Services helped get him set up with a job and apartment, and taught him how to turn the lights on and off — he'd never had electricity before.

"We don’t have these kind of things back in our country," he explains. "They came and they guided us how to use the oven, how to use the microwave, how to use the bathroom."

It was also the first time he'd been around people of other races — and given his experience as a member of a minority group back in Myanmar, he was terrified.

"At the beginning, when we saw white people, we were scared. When we saw black people, we were scared. Later, we got to know the American people, and now we're not scared anymore."

Now 25, Islam works at an international grocery store and recently married a fellow Rohingya refugee. He's become more comfortable speaking English — his fourth language, in addition to Rohingya, Bengali, and Urdu. Things were going well.

Then, on August 25, the Burmese military began burning Rohingya villages and killing people on sight. Islam's parents and siblings left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing, he says. The journey to Bangladesh on foot during monsoon season was difficult, and his father died along the way as a result of the harsh conditions.

"In my head, I am crying, but my mother always advised me, don't cry and don't lose your hope," Islam says. "If I am crying, then there is no way I can help anybody."

Still, the stress has caused him to lose 15 pounds over the past month, he admits. He wants to bring his mother and siblings to the United States, but refugee admissions have plummeted as the Trump administration's travel ban is litigated in court.

"I'm not sure if I will be able to bring them here," Islam acknowledges. "If I can find a way, I definitely will, but with the rules and regulations I'm not sure how it's going to work."

On Sunday night, he and other Rohingya refugees held a vigil on the Old Main Lawn at Arizona State University.

Organized by the Islamic Community Center of Tempe and Islamic Center of the Northeast Valley, it drew a diverse crowd of student activists, local faith leaders, and refugees from around the world. They held up signs calling on Aung San Suu Kyi — the country's de facto leader, and, ironically, a former winner of the Nobel Peace Prize — to put an end to the violence against the Rohingya.

"What will you tell your children, if they ask what you did when the Rohingya were being persecuted?" one speaker asked.

As students passed by on their way to dinner, volunteers chased them down and stuffed flyers into their hands. They urged anyone who would listen to contact the U.S. ambassadors to the United Nations and to Myanmar, and donate money to Helping Hand for Relief and Development, which is sending food packages to Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.

But mostly, they hoped that their presence, along with their signs and pamphlets, would remind people that the Rohingya exist — but that existence is threatened.

"When we put this on social media, then people all over the world will see — they’re protesting for us," Islam said. "People don’t know what’s happening in Burma. We have to talk about it, so that people will get to know."