Marc Raciti said that he and the tree shared a connection. This was the tree he chose to hang himself on.

“We’re both strong and had this greatness about us, but we’re both broken,” he said.

He wrote the notes, he brought a rope, and he was prepared to go. But instead, he fell asleep leaning on the long roots that formed a natural armchair. He dreamed of the drop from the tree branch and waited for whatever version of the afterlife would present itself.

He woke up and decided to seek help.

Marc is shy to talk about how he met his wife, Sonja, at Schofield Barracks army base in Hawaii. He lets her do most of the talking about how they were set up by a mutual friend and waited a whole year to meet to each other.

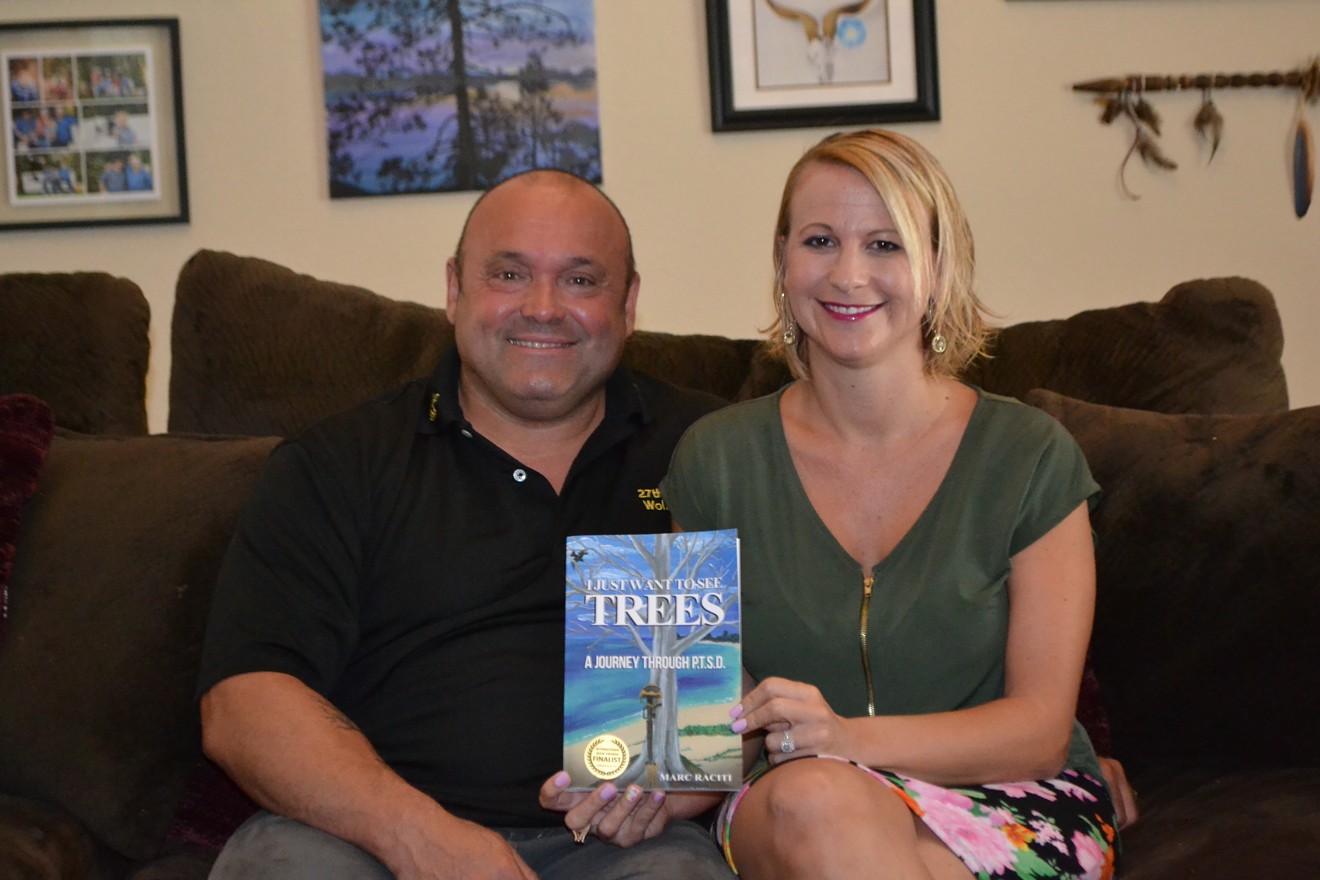

But when it comes to the mental health of veterans, Marc is quick to speak up. He’s written and published a book on the subject, specifically centered on his own journey.

His self-published novel, I Just Want to See Trees, was recently named a finalist in the International Book Awards for two categories, Health: Psychology/Mental Health and History: Military, earning the book a small golden sticker on the front cover.

The title and cover are a tribute to the large, dead tree Marc considered hanging himself on. He named the tree, and the poem it inspired, "Unforgiven."

Marc enlisted in the military as a private at 25 and retired 24 years later as an Army major. He was deployed five times and “frequently provided good medicine in bad places” as an orthopedic physician assistant.

Marc Raciti has tattoos displaying his military background as well as an illustration of the tree he named his book after.

Lindsay Moore

Now the couple lives in Scottsdale with their two sons, dog, Douglas, and cat, Sassy.

Together, they tackle PTSD from all angles in I Just Want to See Trees, in which Sonja also writes about how war trauma can affect family members of veterans.

This was one of three goals they hoped to accomplish: to “offer spouses parts of missing puzzles,” to educate the public, and to heal through vulnerability.

So far, they've already checked all three boxes.

Marc recently received a Facebook message from a reader who told him that the reason he was “on this side of the ground” was because of Marc's book.

“I have helped a lot of people and I helped myself,” Marc said.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs' largest analysis of veteran suicides was published in 2016 based off national data from 1979 to 2014.

Veterans made up less than 10 percent of the overall U.S. population in 2010, but 22 percent of all suicide deaths among U.S. adults were veterans.

After the VA scandal that began in Phoenix and resulted in a nationwide investigation, the Racitis became skeptical of the VA’s ability to help.

Marc considered applying for a job at the VA in 2014 as the federal investigation was launching an investigation into hospital wait times for veterans. He decided against it, saying he didn’t want to “join a sinking ship.”

This lapse in care is partly what inspired Sonja’s practice and Marc’s book.

“Private citizens had to fill in the gap where the government failed,” Sonja said.

The VA sees this gap and is working to fill it, VA Suicide Prevention Coordinator Joey Carr said.

Last year, the VA installed a "press one for veterans" option on the Veteran Crisis Line that redirects callers to the national hotline so they can speak with someone immediately.

From there, a veteran can choose to disclose where they are from and if they want to set up services locally, in which case they would be directed to coordinators like Carr.

"They're (the VA) waking up and saying, 'Let's do that, let's try this,'" Carr said. "There's a huge awareness. People need to know the VA is working on it."

On average, 20 veterans died from suicide each day in 2014. Of those, only six were users of VA services. This statistic has propelled more outreach on the VA's part in an effort to get more veterans signed up for services.

"The message is if you receive VA services, you're two-thirds less likely to commit suicide, and that's because we ask all the time," Carr said.

One of the VA's mandatory regular visits includes a mental-health checkup in which a provider asks point blank if the patient is experiencing suicidal thoughts. For veterans already receiving mental-health services, the question is asked during any type of visit.

This persistence is a way not only opening up the conversation but also to create a reminder for the veteran. Carr said she learned that, on average, it only takes 10 minutes for veterans make the decision to end their lives, find the means to do it, and go through with it.

This makes prevention that much harder.

In response, the suicide-prevention coordinators try to set up safeguards, like gun- or medicine-cabinet locks, with both veterans and their families.

Carr is located at the Prescott office, which gives care to an older population of veterans. The 2014 data shows that the age of approximately 65 percent of all veterans who died from suicide was 50 years or older.

While the memories of combat are still painful for many veterans, Carr said she is most concerned for younger veterans who may not have found coping strategies or a support system yet.

"These are fresh traumatic injuries these veterans are walking in with," Carr said. "The young veterans are such a critical area that we need to pay attention to."