Ray Stern

Audio By Carbonatix

Nearly 20 environmental, religious, tribal, and mining-reform organizations in Arizona are calling on the U.S. Forest Service to redo a key environmental review for a proposed copper mine east of Phoenix.

The draft Environmental Impact Statement, as that report is formally known, violates the federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), these groups say in comments submitted to the Forest Service on November 7. NEPA lays out a complex process of information-gathering, with numerous steps and analyses that must be completed before a major project affecting public lands can begin.

The group’s remarks, totaling more than 6,000 pages including appendices, paint a harrowing picture of the untold risks to people, communities, and the environment that the draft Environmental Impact Statement ignored, overlooked, or diminished.

In language ranging from bluntly demanding to lamenting and poetic, they damn this particular assessment process as corrupt. They say it’s as if the report was designed to reject public opinion and flout federal law, and argue that the Forest Service misinterpreted its regulatory authority.

“The [draft] EIS is inherently flawed and a revised or supplemental [draft] EIS is needed under current law,” the groups say.

They point out that the report failed to provide a healthy mix of reasonable alternatives to the sprawling project, which would cover thousands of acres with the mine plus pipelines, the processing plant, tailings storage, and other facilities.

“The homeowners and ranchers living along Dripping Springs Road have the right to know that, if … a dam failure occurs, whether there would be a viable plan to save their lives or whether they are left twisting in the wind.”

Nor did it fully analyze the potential impacts of those alternatives, they claim, leaving numerous, vital questions unanswered. For example, the document barely mentioned issues such as miles of tailings pipelines that would cross Forest Service lands, should the project go through.

The 18 mostly local groups, which include the Arizona Mining Reform Coalition, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Concerned Citizens and Retired Miners Coalition, the Concerned Climbers of Arizona, the Oklahoma Indigenous Theater Company, the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club, and two separate Audubon Societies, possess “notable expertise in environmental, mining, and social issues,” they write.

The groups say they relied on “numerous professional scientific consultants” in developing their comments, which are sprinkled with painstakingly detailed legal references. They compiled the document over the course of three months, after the Forest Service issued the roughly 1,000-page draft Environmental Impact Statement in early August.

“It’s so transparent that they’re rushing this process,” Roger Featherstone, director of the Arizona Mining Reform Coalition, told Phoenix New Times by phone, referring to the Forest Service. “But there’s really no reason that this can’t be done right … It really puts people’s lives and livelihoods in the balance.”

A Dangerous Plan

If the Resolution Copper mine becomes reality, its operations would ultimately send 1.5 billion tons of waste – rock crushed to a fine sand – to a location somewhere in the mine’s vicinity. Whether it’d be in San Tan Valley, Queen Creek, or elsewhere is undecided.

One of the gravest concerns presented in the groups’ comments is that the Forest Service failed to fully assess all of the potential risks and harms for each of the five possible storage sites proposed to hold these tailings, in part because it didn’t have all the information it needed in the first place.

The Forest Service’s own admission – that it has yet to complete a true analysis of the ways these various storage sites could fail – is buried deep in the draft EIS and clouded in jargon.

So far, the only analysis, known as a Failure Mode and Effects Analysis, or FMEA, for the Resolution Copper Mine has been conducted by Resolution Copper itself – not an independent party, by any stretch of the imagination – using draft documents.

Dan Blondeau, a spokesperson for Rio Tinto, a British-Australian firm which owns a minority stake in Resolution Copper, said that the company used safety guidelines from the Canadian Dam Association “to identify failure modes.” He said that “conservative design features” meant that all possible storage facilities could withstand a 10,000-year seismic event. He added that those features are “in line with CDA and British Columbia Ministry of Energy and Mines.”

The company’s analysis is 127 pages.

According to the draft EIS, the Forest Service eventually plans to lead “a collaborative group process” to create “a more robust and refined FMEA” that would identify possible failures for each of the potential storage sites, along with the likelihood and the severity of those failures and “possible controls” to limit those risks.

That analysis would be done after the draft EIS and before the issuance of the final EIS. Such timing exempts it from the public scrutiny and review that the draft EIS receives.

To emphasize what’s at stake, critics of the Resolution Copper mine have pointed to other serious tailings dam failures, such as the deadly collapse of a storage site in Brazil in February. Its dam gave out, unleashing a nightmarish torrent of toxic waste that killed more than 100 people.

In response to questions from New Times about why a refined FMEA wasn’t included in the draft, and whether the public would have the chance to comment on it, Tonto National Forest spokesperson John Scaggs said an objection period would begin once the final EIS is published.

That publication is expected in summer 2020, according to the Forest Service.

“People who have previously submitted comments will be able to object to content – such as the FMEA – at that time,” Scaggs said.

The Forest Service would respond to substantive comments received during the comment period “in the form of changes in the Final EIS, factual corrections, modifications to the analyses or the alternatives, or an explanation of why a comment does not require the Forest Service’s response,” he added.

For the groups opposing the mine, that’s not good enough.

“The homeowners and ranchers living along Dripping Springs Road have the right to know that, if the preferred alternative” – a tailings facility at Skunk Camp – “is chosen and a dam failure occurs, whether there would be a viable plan to save their lives or whether they are left twisting in the wind,” the groups’ new remarks on the project say. “It is simply inconceivable that Resolution Copper, the perpetrator of the danger to local residents, is helping to write this plan, but not the folks at risk.”

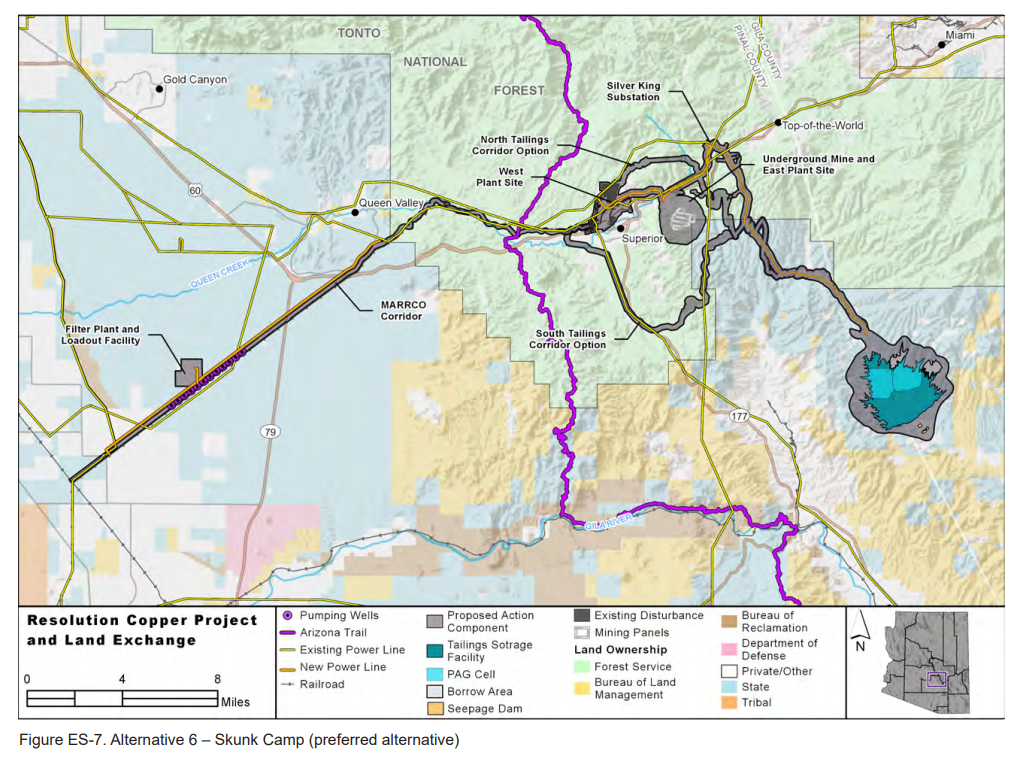

The small, gray bulb near Superior shows where the proposed mine would be. The Forest Service’s preferred site for storing waste, at Skunk Camp, is the teal swatch.

U.S. Forest Service

In their comments, the groups cite evidence of volcanic activity near Skunk Camp. “Local residents point out unusual ground movement in the nearby Pinal mountains and of a sulfur vent in mine shaft near Dripping Springs.”

In fact, the draft EIS refers casually to how little the Forest Service and Resolution Copper have so far probed the possibilities of deadly emergencies.

“Sufficient information on the design and specifications of each component is needed in order to understand how the components would function as a system, and how they might respond to the anticipated stresses on the system,” it states.

At the same time, in terrifyingly broad strokes, it acknowledges the very real, “unavoidable” risks of mining activities.

“Consequences of a catastrophic failure and the downstream flow of tailings would include possible loss of life and limb, destruction of property, displacement of large downstream populations” – as many as 600,000 people – “destruction of the Arizona economy, contamination of soils and water, and risk to water supplies, and key water infrastructure like the CAP [Central Arizona Project] canal,” it says.

To the groups protesting the draft EIS’s many inadequacies, the omission of a careful, practical analysis of these risks and many other concerns – air pollution, water pollution, environmental justice, water consumption, the dewatering of seeps and aquifers, climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, the destruction of cultural resources and land sacred to the Apache, animals including endangered or at-risk species – represent the failures of the document at large.

The government’s assessment of the options for storage facilities was “hurried and incomplete,” the groups write – “symptomatic of a more deeply rooted and nearly pervasive DEIS flaw.”

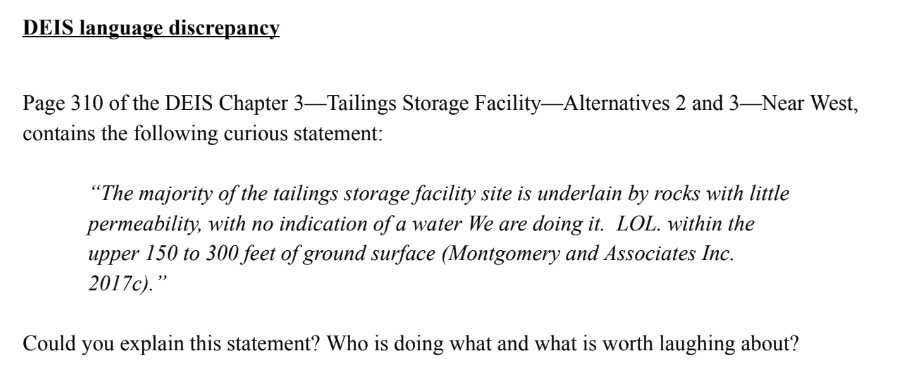

As evidence of the Forest Service’s haste, they point to a paragraph in the draft EIS’s third chapter, into which a rogue sentence and acronym – “We are doing it. LOL.” – somehow landed.

Evidently, no one edited this section of the draft EIS.

Arizona Mining Reform Coalition

“Could you explain this statement?” the groups tell the Forest Service in their comments. “Who is doing what and what is worth laughing about?”

Scaggs, the Tonto National Forest spokesperson, downplayed concerns.

“The Draft EIS is simply the first draft of the Environmental Impact Statement,” he said.

Featherstone disagreed.

“The Forest Service is flat out wrong on that one,” he said. “The purpose of the draft is to lay out what you think is your best shot at what you want to have happening,” he explained. Then, the public, government agencies, and anyone else pick it apart and offer suggestions.

“If you don’t have that best guess in a draft, then you’re really giving the process short shrift, and that’s certainly what’s happened here,” Featherstone said.

‘To Slip the Strictures of NEPA’

Any environmental impact statement under the National Environmental Policy Act must contain a brief statement that spells out the purpose and need of a project.

That statement “is crucially important because it dictates the range of reasonable alternatives to the proposed action,” say the groups. “The purpose and need cannot be so narrow as to limit the range of reasonable alternatives.”

In essence, if the purpose of a project is so constricted that there can be only one way to achieve that purpose, then the alternative scenarios required by NEPA are pointless. They aren’t true alternatives.

But that is precisely what the Forest Service’s draft EIS for Oak Flat does, the groups argue, pointing to rulings in previous public land disputes.

“‘One obvious way for an agency to slip the strictures of NEPA is to contrive a purpose so slender as to define competing “reasonable alternatives” out of consideration (and even out of existence,'” their comments say, quoting from a 1997 case in federal appeals court, Simmons v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The draft EIS for Oak Flat lays out a highly specific purpose and need. Part of it goes like this: “a proposed mine plan governing surface disturbance on NFS lands outside of the exchange parcels from mining operations that are reasonable incident to extraction, transportation, and processing of copper and molybdenum.”

That description diverges grandly from the actual proposed project laid out elsewhere in the draft EIS: “a mining plan of operations on NFS land associated with a proposed large-scale mine.”

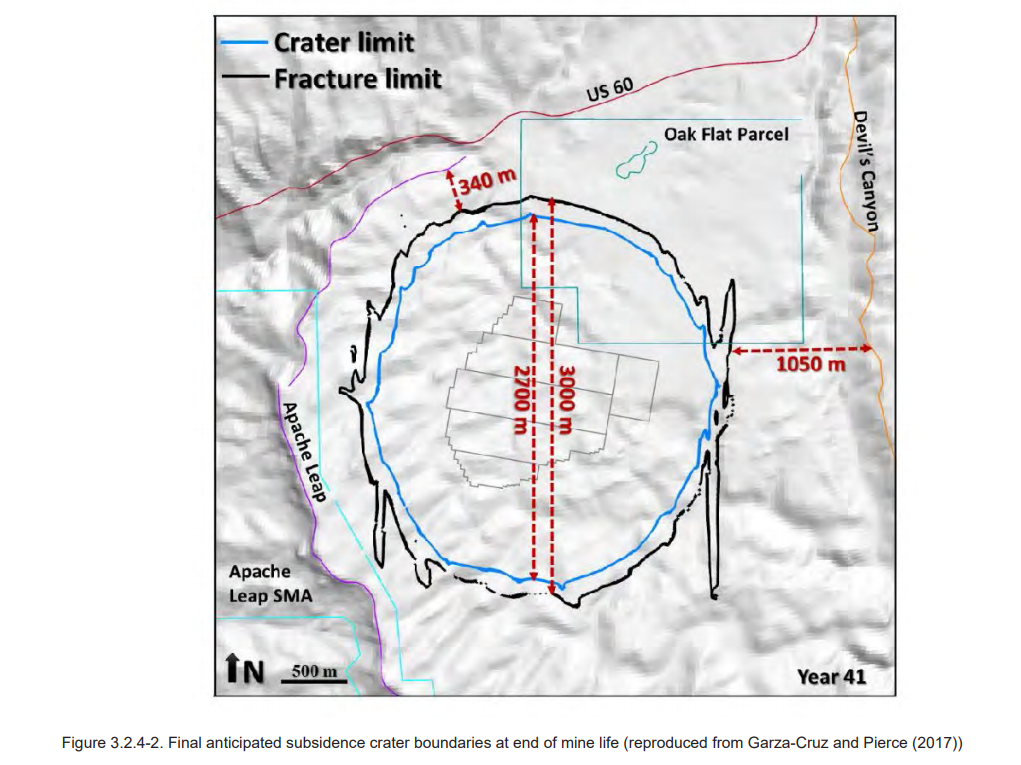

The lack of alternatives shows in the draft EIS, which considers just one method of mining, which is so destructive that it would eventually create a crater about 1,000 feet deep and nearly 2 miles wide – an educated estimate, at best, the groups say – and dismissed all others as prohibitively expensive. It does, however, list six different sites it considered for dumping and storing the mine’s toxic leftovers.

U.S. Forest Service

The groups say that when the Forest Service solicited public comments for an early stage of the review process, it suggested mining alternatives that were never addressed in the draft EIS.`

One of those options was to reopen the San Manuel mine in Pinal County northeast of Tucson, which closed in 2003, just as the initial proposal for Resolution Copper had gotten underway.

San Miguel was owned by BHP, a British-Australian company that owns a 55 percent stake in Resolution Copper (Rio Tinto owns the rest), and it was shuttered “with at least a 30-year supply of copper and expensive mining equipment was left underground,” the groups’ comments state.

But the Forest Service never even examined San Manuel or assessed whether mining there would be viable, they say.

In an emailed response, Blondeau, a spokesperson for Rio Tinto, ignored detailed questions from New Times about issues raised in the groups’ comments. Instead, he thanked commenters and lauded the close of the public comment period as “a significant milestone for the Resolution Copper.”

‘Can’t Say No to That’

In a last-minute addition by then-Senators John McCain and Jeff Flake to the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress required the federal government to exchange land with Resolution Copper. A total of 2,422 acres of National Forest, including where the future mine would sit, would go to Resolution Copper; in exchange, the federal government would receive 5,376 acres currently owned by Resolution Copper.

Even though the draft EIS has been published, the Forest Service has yet to carry out the legally required appraisal of the lands slated for exchange. Nevertheless, by law, the land exchange must go through “not later than 60 days” after the final EIS is published.

“Less than one page of the DEIS is devoted to the appraisal of selected and offered lands,” the groups wrote. “The DEIS gives no explanation why appraisal information is not available and is mute on when the public might see it.” Elsewhere, they raised concerns that the lands to be traded were not of equal value, as required by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act.

Featherstone, who has sought information from the Forest Service about the appraisal but received none, said he worried about the appraisal receiving public scrutiny.

“We don’t know when we’ll get the right to comment on it,” he said.

To make a complex project even more confusing, the same EIS is supposed to cover not just the land exchange, but also the general plan of operations submitted by Resolution Copper – the two major components of the entire project.

The combination effectively fuses two distinct elements of a hotly controversial project into a single decision.

To Featherstone, of the Arizona Mining Reform Coalition, that merger doesn’t change the fact that the project actually entails two sets of decisions: the land exchange and the mine itself.

“The [Defense Authorization Act] says nothing about, ‘You have to give them the land and you have to allow a mine to built,'” he said. “It’s not specific at all about what you have to do or don’t do with that land.”

Scott Tressler of the Arizona Mining Association looks on as Sandra Rambler of the San Carlos Apache finishes speaking at the public hearing in Tempe on October 10, 2019.

Elizabeth Whitman

Requirements in the 2015 law also don’t give the Forest Service license to abandon other federal laws – namely NEPA, the Clean Water Act, the Forest Service Organic Act, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, among others, the groups say in their comments. Nor does it mean that it must automatically ignore the no-action alternative.

But Tonto National Forest Supervisor Neil Bosworth, who is tasked with this decision, has repeatedly said that he cannot choose the no-action alternative.

After a public meeting in Queen Valley in October, Bosworth cited the 2015 NDAA, telling New Times, with some prompting from spokesperson Scaggs, that the land transfer was congressionally mandated.

“There’s no decision to be made,” Bosworth said. “I can’t say no to that.”

As for the mine itself, he pointed to Forest Service policy and the 1872 mine law.

“I can’t say no to a mine,” Bosworth said.