Tom Carlson

Audio By Carbonatix

Hundreds of feet beneath a residential neighborhood in Maryvale, toxic chemicals have been leaching into the groundwater.

Arizona’s top environmental regulator deemed this square-mile site a major contamination site last fall. It’s the latest in Maricopa County to be added to the state’s Water Quality Assurance Revolving Fund list, which catalogs environmental investigations and cleanups.

Groundwater contamination has plagued communities across Arizona for decades, hindering the use of precious aquifers. Over the years, some cleanup efforts have been more successful than others.

But it’s becoming more critical than ever for the state to have a strategy to transform polluted groundwater into potable drinking water at best and safe irrigation water at worst as the state’s population and water demands continue to swell.

This new site is a reminder of the challenge.

The plume of several industrial solvents is bounded by Indian School Road to the south and Camelback Road to the north, between 45th and 57th avenues. Environmental investigators are still determining the extent of the contamination. So far, they don’t believe that anyone is drinking the tainted water.

Neighborhoods in the area are largely working-class. The lack of community resources could pose a challenge to rallying residents around a lengthy cleanup effort, said William Owens, a Maryvale resident who sits on the community board overseeing the cleanup.

“We all go to work, we all come home,” he said. “Some of the guys that work in this neighborhood are out in the sun all day long.”

“Most of the neighbors, if it doesn’t come out of the faucet, they’re not going to care,” he said.

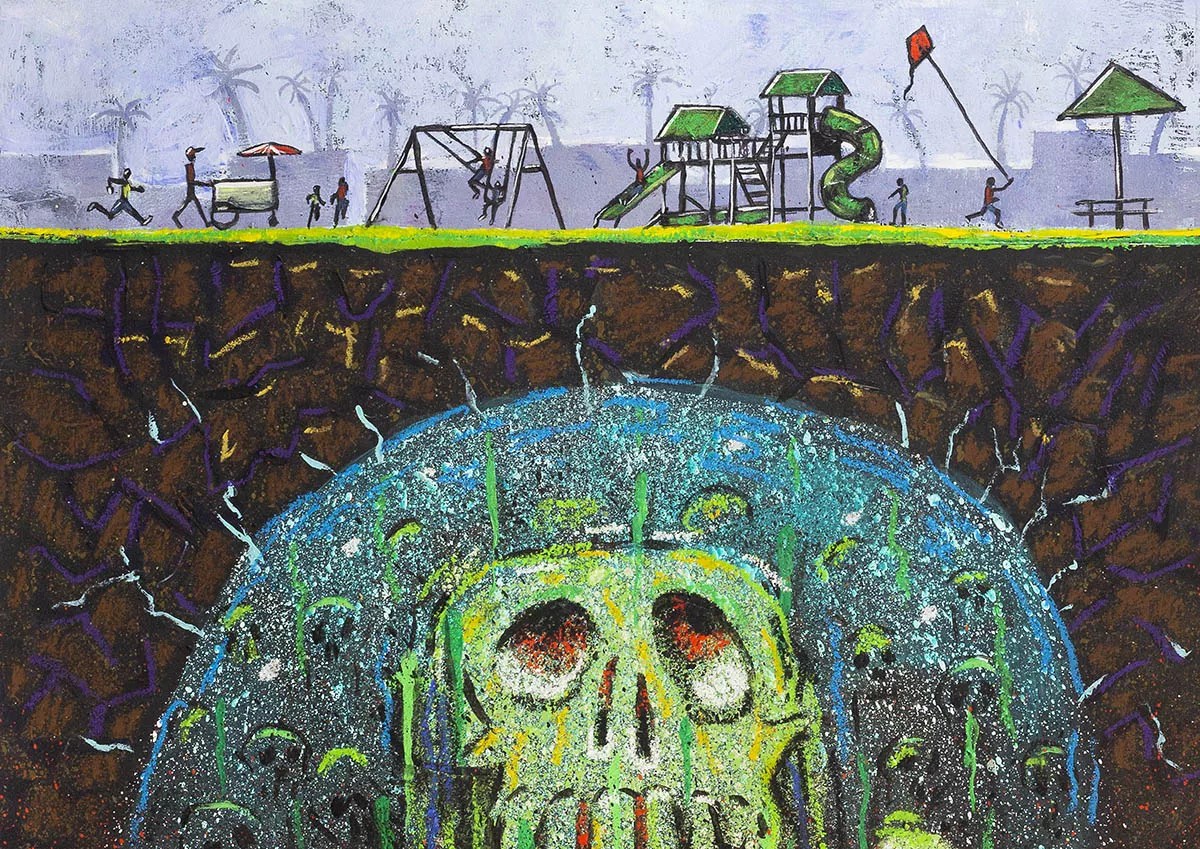

Maryvale Park sits at the heart of a recently discovered toxic groundwater plume.

Ash Ponders

The West Valley in particular has a long history of environmental contamination. In the 1950s and ’60s, industries began to replace farmland in West Phoenix. Aerospace manufacturers and semiconductor factories such as United Industrial set up shop, turning the area into a booming industrial zone. Though many have now shuttered, they left behind a legacy of pollution.

The latest toxic plume to be discovered, however, is an orphan site. State investigators have not yet identified its source.

The cleanup could cost millions. Motorola’s two flagship factories in east Phoenix released toxins such as cleaning solvents, acids, and cyanides into the city over decades. The company spent more than $30 million on remediation efforts.

As such, environmental activists are watching the state’s response to the new site closely.

During a sparsely attended community meeting recently, ADEQ officials gave an overview of the site and their plans for remediation, which will likely take years.

Gianna Trujillo, the project manager, called the contamination “pretty extensive.” That meant a lengthy cleanup, she said.

The contamination has so far only been discovered in groundwater 200 feet beneath the surface. When toxins disperse through a large area of an aquifer, as food coloring would disperse through a glass of water, it is referred to as a “plume.”

ADEQ surveyors found high concentrations of three toxins in the water: PCE, or tetrachloroethene, TCE, or trichloroethylene, and 1,1-DCE, 1,1-dichloroethylene.

In some parts of the site, investigators found levels of TCE and PCE at 1,440 micrograms per liter and 1,730 micrograms per liter, respectively. That’s hundreds of times greater than the state’s water quality benchmarks, which recommend levels no higher than 5 micrograms per liter of each chemical for drinking water.

PCE and TCE are both colorless liquids frequently used as dry cleaning solvents. TCE, in particular, is a common groundwater contaminant, according to the EPA, because it can leach through the soil.

Alan Dulaney, a retired hydrogeologist and municipal water policy administrator, said that once chemicals like TCE and PCE get into the soil, they quickly sink into the aquifers.

“They are denser than, say, contaminants found in gasoline or diesel,” he said. “They tend to move faster, too.”

The EPA classifies both TCE and PCE as carcinogens. Workers exposed to PCE have shown a higher incidence of bladder cancer and lymphoma, while TCE is linked with kidney cancer.

Although there are differing opinions on the dangers of the chemicals, one risk evaluation of TCE in drinking water estimated that exposure to elevated levels of the toxin would cause a “moderate” increase in cancer risk. Exposure to the toxin over decades, the report said, would add approximately two or three additional cancer cases per 1,000 people.

For 1,1-DCE, a chemical used to synthesize certain types of flame-resistant coatings and packing materials, there is less robust evidence of a cancer-causing effect, but it is still considered a “probable” carcinogen by the agency.

The levels that ADEQ measured are “very significant,” according to Dennis Shirley, an environmental consultant who has worked on chemical remediation projects in Phoenix for years. But in Phoenix, that’s not unusual, he said. And it’s one of the reasons the city has largely not relied on its groundwater as a source of drinking water.

On a sunny Thursday afternoon, students filtered out of the Marc T. Atkinson Middle School in Maryvale, some heading onto buses, others gathering at a nearby park and community center.

Several passersby told Phoenix New Times they had heard nothing about groundwater contamination. But this school and park on Maryvale Parkway sit at the very center of the contamination site, which spans roughly a square mile.

The Maryvale neighborhood above the plume is largely residential and poorer than the average community in Phoenix. According to 2020 Census data, the vast majority of residents – 90 percent – are people of color, mostly Latino.

How these communities have been affected by the plume beneath their homes is not yet clear.

Maryvale Park sits at the heart of a recently discovered toxic groundwater plume.

Ash Ponders

The state first discovered the contamination in the area in 2019. Investigators were monitoring an underground storage tank in the area which had a possible leak, officials said. They noticed that, in the surrounding area, there were high levels of TCE.

The contaminated water, as far as the state knows, is not being used as drinking water. In Phoenix, most residents get their water from the city’s canal system, and officials said that there are no known private wells in the area – meaning that the groundwater is not getting into anyone’s tap. It’s possible, however, that there are unregistered wells that the state doesn’t yet know about.

Officials recently urged anyone in the area with an unregistered well to contact the state for testing.

William Owens, a longtime resident of the area, told New Times he was “not sure at all” about the possibility of unregistered wells. “I do not know of anyone personally that has a private well,” he said.

Dulaney, the water expert, said he doubted that any residents of the area were relying on unregistered wells for their drinking water. Most wells built before registration requirements, he said, would have dried up by now, or been paved over. But old abandoned wells could be sources of pollution, if chemicals had been dumped into them, he said.

There is one Salt River Project well in the area, which Trujillo, the site’s project manager, said was an “ongoing concern.”

That well is used for irrigation – not drinking water – but that use might change in the future, she said. The state is currently monitoring levels in that well.

SRP officials told New Times that they are collaborating with the state during the environmental remediation process.

“The city of Phoenix is heavily reliant on Colorado River water delivered by the Central Arizona Project,” said Dulaney. “Over the years, they haven’t invested much in drinking water wells.”

Groundwater currently makes up just 2 percent of the city’s water supply. But now that a worsening drought has dropped the Colorado River to crisis levels, the city might need to rethink its reliance on surface water and consider tapping urban groundwater.

“Cities are going to want their groundwater wells in operating condition, ready to step in,” he said, should the Colorado River drought worsen.

And they will want those wells to be clean.

Furthermore, groundwater contamination could signal a public health risk, even if no one is drinking it.

Contaminants like TCE and PCE typically work their way down to aquifers through hundreds of feet of soil layers, Dulaney said. If the chemicals are trapped in the soil, he said, they could “volatilize” – become vapor and disperse into the air.

“The vapor could work its way back up to the surface,” he said. “It could work its way into basements.”

Shirley agreed: “If you have these solvent contaminants in the soil, and there are workers and residences nearby, that could be a pathway of potential exposure,” he said. Such workers and residents might be breathing in the chemicals.

But it’s too early to say whether the soil in the area has also become significantly contaminated, officials said. Currently, the state is conducting a more extensive investigation of the site to find out.

ADEQ spokesperson Caroline Oppelman emphasized that, as of right now, “data from the preliminary investigation and ongoing remedial investigation show that site groundwater and soil do not pose an imminent risk to public health.”

Another important question that investigators hope to answer in the coming months: Who is responsible for the pollution?

It’s fairly certain that the contaminants are a byproduct of industrial waste in the area, according to Trujillo.

Companies including Motorola, Reynolds Metals (now owned by Alcoa Inc.), and the American Linen Supply Company (Alsco) have all paid out millions in settlements and cleanup efforts for pollution in Phoenix over the years.

Both TCE and PCE are frequently used as solvents at dry cleaning businesses and at vehicle repair shops, for removing grease and clothing stains. Sometimes, these businesses dump the chemicals or the toxins leak from the plants into the soil.

These chemicals are hazardous for workers who come into contact with them on the job. Commercial drycleaning workers’ health has suffered as a result, with maladies ranging from kidney damage to memory impairment.

Once the secondary investigation is complete, ADEQ will begin the cleanup. It will likely use a “pump-and-treat” strategy, officials said, which sucks up groundwater, removes the contaminants, and returns it to the ground.

In some cases, this can take decades.

Environmental activists say they will be watching closely. For years, critics have complained that ADEQ has let other contamination sites in Phoenix languish.

Shirley said he would like to see further action on the West Van Buren contamination site, a toxic groundwater plume that stretches across southwest Phoenix. For years, action on the site has stalled while ADEQ awaits a decision from the federal Environmental Protection Agency on whether the site will be put under federal jurisdiction.

“This is the largest site in the state,” Shirley said, “and they have failed to spend the time addressing it.”

The area of underground contamination that Arizona Department of Environ

New Times map based on Arizona Department of Environmental Quality data

ADEQ is emphatic that the agency has done its due diligence on the West Van Buren site. Oppleman noted in an emailed statement that the agency’s prioritization of sites “is based on exposure risk and how that could potentially impact human health,” and that the site currently posed no risk to nearby residents, who have access to treated drinking water from the city.

“ADEQ looks forward to EPA advancing a path forward for the WVB Site,” she said.

Shirley disputes that there is no public health risk posed by the West Van Buren plume. Currently, the Roosevelt Irrigation District provides water and operates irrigation wells in the area.

Shirley, whose business has contracted with Roosevelt Irrigation District, says that the wells provide for a “direct exposure pathway” to residents by allowing the chemicals to enter the air.

Activists also point out that the West Van Buren plume, like the most recently discovered Superfund site, is located in a poorer part of Phoenix, and largely affects communities of color. The impact of contaminants in West Phoenix dates back decades, to the late 1980s at least, when the state found evidence of a cancer cluster in Maryvale.

Studies of the cluster at the time found that there were twice as many cases of leukemia among children in the community than expected. Researchers estimated that the area saw 20 additional leukemia deaths among those younger than 19 due to the contamination. Some of those families sued the city and factories as a result. Most did not succeed.

Shirley said that he believes that race and class have “absolutely” affected the agency’s response to contamination – in part because well-resourced communities often have the time and money to advocate for state action.

Sandy Barr, director of the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon chapter, said it was “interesting that they are just discovering [the new site],” given the agency’s troubles with effective water quality monitoring.

This fall, a scathing report released by the Arizona Auditor General said that the agency was failing to conduct “key ongoing groundwater monitoring of the State’s aquifers.” It gave no mention of the types of chemicals discovered last year in Maryvale, but the report did generate new scrutiny of the agency.

The department’s failure to develop water standards for multiple contaminants had “put private well users at risk of having unsafe water,” the auditor found. And ADEQ’s cleanup efforts for surface waters had fallen short, the report said.

From 2014 to 2020, the number of polluted bodies of water in the state had increased, it found. About 70 of them – 40 percent – had been contaminated for at least 15 years.

Barr said that, given the agency’s legacy in West Phoenix, it should be collecting better data about the racial and economic disparities in its work.

“We know that environmental racism is prevalent throughout our system,” she said. But without requirements that ADEQ study the issue, such problems were difficult to document.

For now, ADEQ officials say they are doing what they can to spread awareness about the new polluted site among impacted communities in Maryvale. This is why the “community advisory board” was formed last month. One board member, Megan Sheldon, told New Times she had joined to “help answer questions from the community” as the cleanup gets underway.

Owens, the other board member, said he joined to make sure “it’s done right, and make sure it’s done in a timely manner.” This, he said, is not always how cleanup efforts go in west Phoenix.

Maryvale residents are waiting for remediation to begin. Owens said he would be closely watching to see who the responsible party is – to make sure they are held accountable.

“Somebody’s got to pay,” he said. “It can’t come out of everybody’s pocket.”