Ellen Weinstein

Audio By Carbonatix

It was 1972, an election year just like this one, and abortion was a major issue.

Most states did not allow abortion. Many of the state laws limiting or prohibiting it were more than 100 years old, and they were being challenged in state after state and getting overturned by federal judges. The states trying to hold onto them petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court.

Roe v. Wade, the landmark opinion that made abortion available in all 50 states, was argued twice before the high court that year. The question was whether to uphold or knock down harsh abortion restrictions in Texas and Georgia.

Sound familiar? The debate has not changed in more than 50 years.

“The abortion cases are symptomatic,” Justice William O. Douglas wrote in an unpublished 1972 dissent after the first Roe arguments. “This is an election year. Both political parties have made abortion an issue. What the political parties say or do is none of our business. We sit here not to make the path of any candidate easier or more difficult. We decide questions only on their constitutional merits.”

In 1972, the hard part was determining what rights to grant an unborn fetus and what rights to afford the woman carrying the fetus. The Constitution didn’t specify either. Rather than keep batting down vague laws, the justices decided to set guidelines. But where?

The solution came from a young lawyer clerking for Justice Lewis Powell. He convinced Powell to educate the other justices on the concept of “viability,” the point when a fetus was thought capable of surviving outside the uterus. That would be the point when concern shifted from the rights of the mother to the rights of the “potential life.”

Under Roe’s rules, having an abortion would be a decision made by a woman and her doctor for the first trimester, or 12 weeks, of pregnancy. From then until viability, then thought to be 27 weeks, until the end of the second trimester, the state legislatures could set certain restrictions, especially to protect the health of the woman seeking an abortion. And after that, abortions could only be performed in dire circumstances to save the life of the mother.

The Roe v. Wade opinion was released in January 1973. It was modified by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1992 by an opinion called Planned Parenthood v. Casey, but the concept of viability held, and abortion was still legal across the country.

Now we are in another election year, and conservative states, starting again with Texas, have rammed through new abortion laws that resemble the old laws, knowing they would lead back to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court had refused to grant an injunction against a Texas law that violated Roe.

And now, another case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, comes out of Mississippi. The court heard arguments in December. The handwriting is on the wall – and all over the internet, since a draft of the pending opinion was leaked last month.

A formal ruling is expected imminently.

According to the leaked draft opinion, authored by Justice Samuel Alito, much of the nation will return to those now 150-years-or-older laws knocked down by Roe. It would be as if the court had pressed a legal reset button. There is no constitutional right to abortion, it says, and the decisions about regulating the procedure should return to the state legislatures.

That a draft of the opinion was leaked has been called a scandal, something that never happened before.

But it did happen before, if not on the same scale. Roe v. Wade also was leaked to the media, and that leak was caused by the same young clerk who had pushed the concept of viability. He would go on to become a dean of lawyers in Phoenix.

His name was Larry Hammond.

Dean of the Defense Attorneys

Hammond was a tall man with a shock of black hair and wire-rimmed glasses. He stood with a bit of a stoop, as if he wouldn’t want to look down on anyone while making eye contact. His voice was high-pitched, almost creaky, displaying his Texas country roots.

He spoke slowly and deliberately, pausing often, and you wouldn’t think much of it until you knew that he stuttered as a young man and was forever holding it back. And he spoke softly, both metaphorically and literally, a humble man who suffered from a pulmonary disease that eventually killed him in March 2020.

After his stint at the U.S. Supreme Court, he was recruited by the Watergate Special Prosecution team and was tasked with listening to President Richard Nixon’s incriminating secret tapes. Later, he returned to Washington to work in President Jimmy Carter’s Department of Justice on the team attempting to free American hostages in Iran.

When Hammond first left Washington in 1975, he had accepted a job in Los Angeles, but a friend from his clerking days, William Maledon, asked him to stop in Phoenix on his way to visit with him and another former clerk, Andrew Hurwitz.

“He never made it to L.A.,” Maledon said in a recent interview.

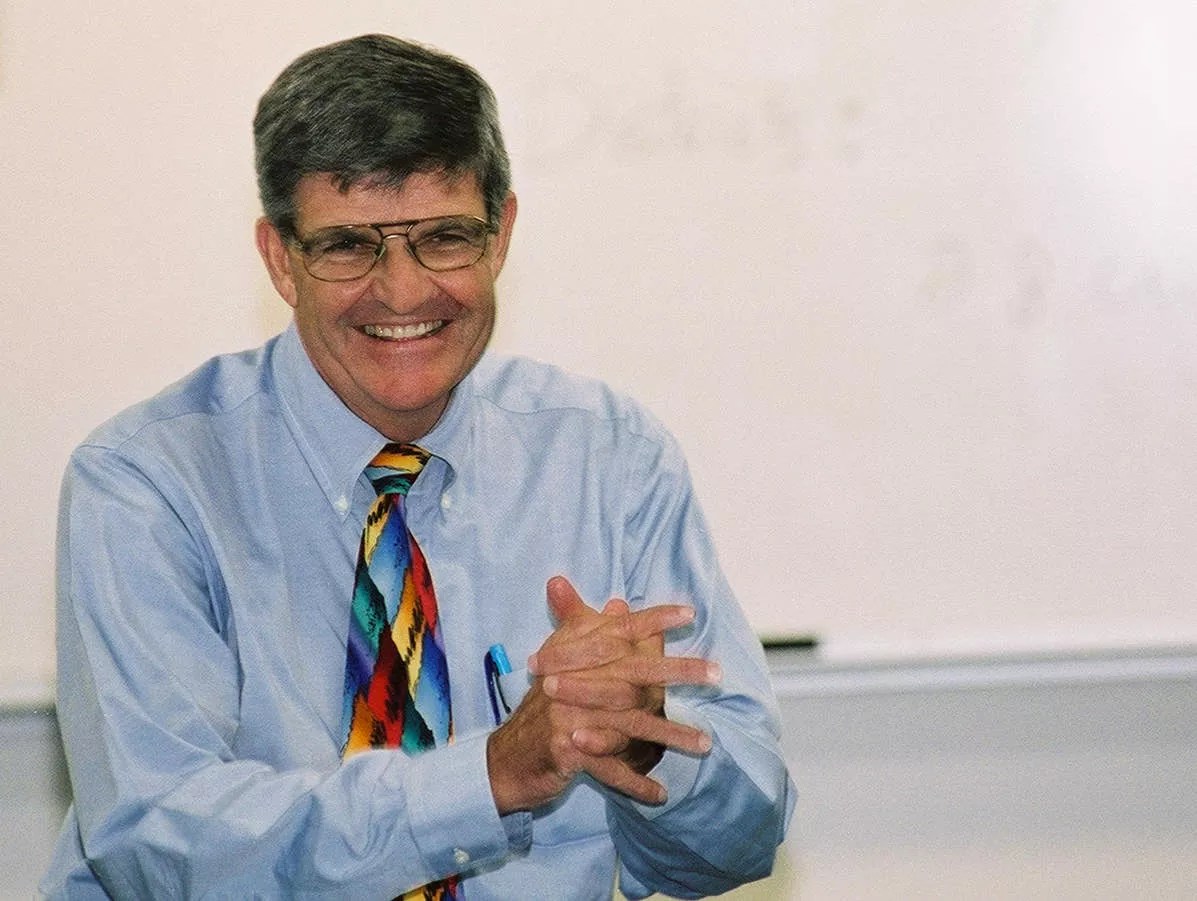

Larry Hammond.

Arizona Justice Project

Instead, Hammond settled into legal practice with Maledon and Hurwitz in the practice that became Osborn Maledon. The three remained lifelong friends. Maledon still runs the firm. Hurwitz became an Arizona Supreme Court justice and now sits on the Ninth U.S.Circuit Court of Appeals.

I spent 16 years covering courts and crime for the Arizona Republic and wrote for Phoenix New Times for eight years before that. During that time, Hammond was a regular source who became a friend. He always picked up his phone when he saw my number flash on the screen.

I’d run into him at spring training or Diamondbacks games. He was a baseball fanatic with season tickets. He knew all the beer vendors and ushers, but no one was allowed to talk to him during the game, because he was busy with his scorecard. Occasionally, we would get a beer to talk about the state of legal affairs.

He was an expert I consulted for many stories, though until now, he was never the story himself, nor would he want to be. I and our mutual friend, Dale Baich, find it hard to remember specific conversations with Hammond – which probably means he was doing more listening than talking.

But there he was, testifying before Congress about capital cases, signing an op-ed piece in the Washington Post about impeachment, lecturing a law school class on lost cause appellate issues.

What he was proudest of was founding the Arizona Justice Project, which offers legal help to lost causes, prisoners who proclaimed innocence but have exhausted the scant appeals and government-paid defense attorneys the system offers.

“Larry thought there ought to be a place where people in prison can write for help,” said Lindsay Herf, executive director of the Arizona Justice Project.

The Justice Project took the side of battered women who had been convicted for fighting back, arsonists convicted by faulty science, and defendants sentenced to decades in prison for a $20 rock of crack cocaine.

“No matter how big or how little it was, Larry was always there,” said Katie Puzauskas, a director of The Justice Project.

At the same time, Hammond took on cases at Osborn Maledon.

“He was always worried that people’s rights were trampled on,” said Maledon. Hammond wanted to fight for them.

“The firm gave him the resources to do it,” Maledon said. “Lots of resources.”

Baich, a recently retired federal defender who specialized in death penalty cases, recalled Hammond commenting on a colleague who came across too strongly, like, he said, a shrill abolitionist.

“He suggested a more toned-down, reasonable approach,” Baich said. “That was Larry: Be credible, be reasonable, and do not demonize the opposition.”

We, as friends and colleagues, knew Hammond had worked on Roe v. Wade. There were murmurs and rumors. We knew he had been a Watergate prosecutor. The connection to the Iran hostages caught me completely by surprise. He never talked about any of those cases, at least not to those who knew him in Phoenix.

“All of us wish he had talked more,” Herf said.

Some of it was the nature of clerking at the Supreme Court.

“You understood from the first day that all of it was confidential,” Maledon said.

In his later years, Hammond recalled his Watergate days, especially when former President Donald Trump was being impeached. And he was free to talk about his clerking days because Justice Powell released his former clerks from the code of confidentiality.

Hammond gave up talking about Roe v. Wade, however, after participating in a debate on the subject at Notre Dame University with soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. It became quite heated, according to James Robenalt, an attorney in Cleveland.

“I decided I should plow other fields,” he told Robenalt.

But Hammond did talk to Robenalt, in 2013, for a 2015 book the Cleveland lawyer wrote titled January 1973: Watergate, Roe v. Wade, Vietnam, and the Month That Changed America Forever.

And Hammond’s memos and fingerprints are all over the archived papers of Justice Lewis Powell.

Sex and the ’60s

Hammond was born in El Paso, Texas, and he attended the University of Texas, where he majored in Russian, partly because he discovered that he did not stutter when he spoke foreign languages. He stayed in Texas for law school.

The stutter may have played a part in his clerkship. He had strong academic credentials, of course, but Justice Hugo Black, in the last part of his career on the bench, started hiring clerks that he thought he could improve and teach life lessons. The stuttering Texan was one of Black’s last projects.

Black and a second justice, John Marshall Harlan II, resigned for health reasons in fall 1971, leaving two vacancies on the court. They both died that year, Black in September and Harlan in December. Hammond was left with a job but without a justice to clerk for. So, as he told Robenalt, he played a lot of basketball in the court above the Supreme Court building, jokingly referred to as “The Highest Court in the Land.” He gave tours to school groups and kibitzed with Justice Thurgood Marshall. And, Hammond told Baich, he was fulfilling a death-bed wish of Justice Black – burning some of his papers.

Then as now, the country was in turmoil.

The late ’60s and early ’70s were a time of great political and social upheaval.

“Sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll” was not yet a cliche. “Generation gap” was the phrase coined to describe the debates and sometimes violent clashes between baby boomers and their parents, the self-named “Greatest Generation,” over nearly everything from haircuts and music to civil rights, the war in Vietnam, and whether the voting age should stay at 21.

The sexual revolution was in full swing, but it was complicated. Birth control was not always an option. It was not always available and not always legal. In only 1965, the Supreme Court had knocked down laws prohibiting contraception, and then only for married couples. Birth control pills were not readily available until Nixon signed a family planning law in 1970, making them widely affordable.

Protesters at the Supreme Court protest the leaked Alito draft of a decision overturning Roe v. Wade.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

In 1972, abortion was available on demand in only four states, but three of those required that the patient live in-state. Thirty states prohibited abortion in any circumstances and 16 others set restrictions.

Nonetheless, according to a study published in 2012 by the National Bureau of Economic Research, nearly 453,000 women had legal abortions in 1971 and 503,000 in 1972. There’s no way of knowing how many illegal abortions were conducted.

Abortion was not contraception. It also was not theoretical. Or easy. It was a desperate act, and just because it was illegal in many places didn’t mean women didn’t risk their lives to do it.

I knew one 19-year-old woman who was not prepared to have a child and was terrified to tell her parents she was pregnant.

She sought out an abortionist who pierced her with a knitting needle and gave her medicine that would thin her blood until she miscarried. The miscarriage took place while she was in the dorm room of the women’s college she attended in New Jersey.

The dean of the school, at first, wouldn’t let the male paramedics onto the gated campus, and she nearly bled to death. She survived. But the school’s response was to have her expelled.

That woman was my sister.

A year later, she could have obtained a legal abortion in nearby New York. The New York State Legislature had passed what was then known as an “abortion on demand” law. Two years later, the legislature voted to repeal it, but Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican, vetoed the bill.

Women flocked to New York for the procedure, and more than half of all legal abortions in the country were performed there in 1971 and 1972. In the latter year, 15,522 women just from the state of Michigan traveled to New York for abortions, and some doctors advertised package deals that included airfare, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research study.

In the states that imposed restrictions on abortion, the laws varied. Some prohibited it altogether, while others allowed it in instances of rape, or to save the mother’s life.

Some more ambiguously allowed abortion to preserve a woman’s health, but that was a matter of interpretation: Did it mean her physical health, or could it also mean her mental health? It was not as easy to get a doctor to vouch that a woman needed an abortion to preserve her health as it was for a man to get a doctor to diagnose bone spurs and spare him from being drafted into the military. The woman often had to pass muster with a hospital committee.

The Abortion Rights Battles

The legal precedents piled up.

Numerous cases landed at the door of the Supreme Court, and in 1971, the court chose to hear Roe v. Wade.

The case was filed under the pseudonym of Jane Roe, an unmarried pregnant woman, who did not meet the life-saving medical requirements to get an abortion under Texas law.

But it was actually two cases, with three plaintiffs besides Jane Roe in the Texas case and a separate case called Doe v. Bolton, which challenged abortion laws in Georgia.

The court was in transition, however. It was short two justices. Nixon nominated William Rehnquist, an attorney from Arizona, to replace Harlan, and Powell, who was from Virginia, to replace Black. They got through Senate confirmation quickly, but could not be sworn in until January 1972, too late to participate in Roe v. Wade arguments the month prior.

The seven-justice panel ruled 5-2 to uphold the lower court decisions and knock down the Texas and Georgia laws. Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the draft opinion of Roe, throwing out the Texas law on grounds that it was constitutionally vague.

That didn’t sit well with the court, according to memos in the files of Powell and other justices, which have been made public. Several justices began lobbying to rehear arguments with a full panel, including the two newly appointed justices, Powell and Rehnquist. Justice Douglas objected, fearing that some justices would waver and turn the decision around. Chief Justice Warren Burger wanted it re-argued.

“Part of my problem arises from the mediocre to poor help from counsel,” Burger wrote in a memo to the other justices.

And he wanted more amici, friends of the court, appointed to weigh in. “This is as sensitive and difficult an issue as any in this court in my time,” he wrote.

Other justices thought the vagueness argument did not fit. The second arguments were to take place in October 1972 in front of a full panel of nine justices.

Justice Powell hired Hammond as a clerk, and the two initially got off on the wrong foot. In January 1972, in a case called Furman v. Georgia, the high court abolished the death penalty on a 5-4 vote, saying that the way it was applied was too arbitrary. But that is where the agreement ended. All nine justices wrote separate opinions. The death penalty was not reinstated until 1976, in another Georgia case that established the consideration of aggravating factors to more narrowly distinguish capital cases from other murders.

Powell was among the dissenters in the 1972 case. Hammond was charged with drafting his opinion, but the two were on opposite sides of the issue. Hammond offered to resign, but Powell asked him to stay on. When the court went into summer recess, Hammond stayed in Washington to study abortion law and arguments, including Blackmun’s draft opinion in Roe, and prepare a memorandum for Powell to familiarize him with the facts.

He became Powell’s go-to man.

What About the Women?

On December 9, 1972, two days before the second arguments in the Roe and Doe cases, Hammond penned a bench memo to prep Powell on what the various justices and the court records said.

He noted “a fundamental right of a woman to decide for herself whether she wished to continue her pregnancy,” which the lower courts upheld. He noted the ambiguity of statutes that opined on the life and health of the pregnant woman and questioned how much the attending doctor should have to say in that decision.

“It would not be difficult for this [court] to find a fundamental right of a woman to control the decision whether to go through the experience of pregnancy and assume the responsibilities that occur thereafter,” he wrote.

But on the other hand, he added, “Because of the existence of a compelling state interest in the life of the baby, and because of an interest in the health of the mother, the state may regulate abortions to some extent.”

Near the end of the memo, Hammond hinted at a solution to “weigh the state’s countervailing interest in protecting the life of the unborn.”

“With that thought in mind of suggesting a convincing rationale for the balancing problem presented, I have read carefully Judge Newman’s recent Connecticut opinion and have attached a copy for your use. (This was drafted in part by Andy Hurwitz so you may gain some feeling as well for his writing ability.)”

Hurwitz and Hammond did not yet know each other. They met a few years latter, ostensibly, when Hurwitz signed on to clerk for Justice Potter Stewart. But Hurwitz had recently clerked for Judge Jon Newman of the District Court for Connecticut, who sat on a District Court of Appeals panel that threw out the restrictive Connecticut abortion statute.

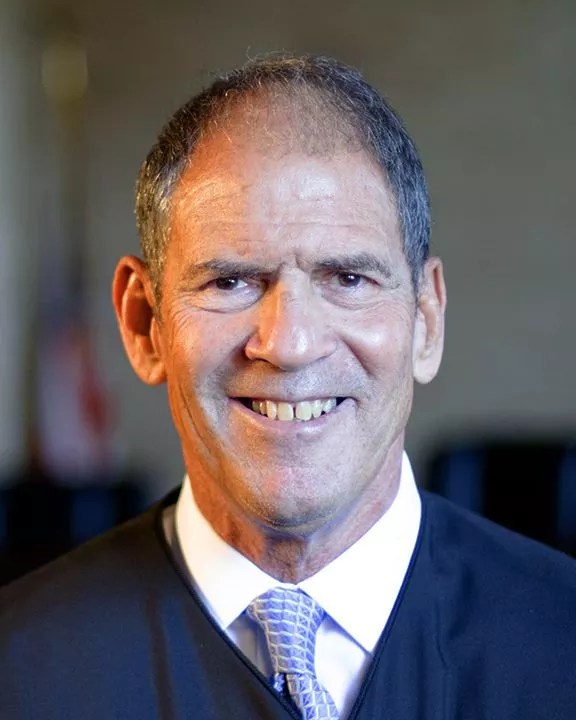

U.S. Court of Appeals judge Andrew Hurwitz, a friend and associate of Hammond’s.

U.S. Court of Appeals Handout

Newman wrote the opinion, and it presaged issues that would loom large in Roe. How much privacy was a person owed in matters of sex and family? Was a fetus a person “having a constitutionally protected right to life? And if not, could the state set “a purely statutory right at the expense of another person’s constitutional right?” Further, if a fetus was protected because it was a potential human, what about an unfertilized ovum? These were difficult questions, and no one had the right to impose his or her personal beliefs on others.

The law needed to be more specific. One solution might be for the legislators to consider “viability,” Newman said.

“While authorities may differ on the precise time, there is no doubt that at some point during pregnancy a fetus is capable, with probable medical attention, of surviving outside the uterus,” he wrote.

Newman left it there without dictating anything to the state legislators.

It planted a seed at the Supreme Court.

Hurwitz has denied that he, in fact, authored the opinion, despite what Hammond wrote in his memo. In a footnote to a law review article about the Newman opinion Hurwitz published in 2003, he wrote that Justice Stewart jokingly used to call him “the clerk who wrote the Newman opinion,” but dismissed it as exaggeration.

And it haunted him later in his career, specifically during his 2012 U.S. Senate confirmation hearings, when Republicans threatened a filibuster to block his nomination because of what they perceived as his views on abortion.

He declined comment for this article through a spokesman, “passing on his kind regards, but to say that he doesn’t want to comment on Roe while the Supreme Court controversy is still growing.”

Making the Sausage

By the day’s standards, the Burger Court was anything but liberal. Four of the justices had been appointed by Nixon. But they still voted 7-2 to uphold the lower court rulings and knock down the Texas and Georgia abortion statutes. Justices Rehnquist and Byron White dissented.

Then it was time to make the sausage.

Bill Maledon was clerking for Justice William Brennan, who voted with the majority, but found the matter difficult, as he was a Catholic.

“He was trying to take the religious issues out of it,” Maledon said.

Maledon frequently played basketball at “The Highest Court in the Land” with Justice White, who had been a noted collegiate athlete. White asked what the constitutional basis was for the majority decision, calling it “almost metaphysical.”

“I think what everyone was struggling with was how do you get to a principled explanation?” Maledon said.

In a memo to Rehnquist, November 27, 1972, Blackmun, who was writing the majority opinion, said that he still felt the statutes were vague.

“I do not know, and I doubt any physician can know, what is meant when the statute speaks of ‘the purpose of saving the life of the mother,'” he wrote. “My vagueness, however, did not find favor.”

Then he assured Rehnquist, who was opposed outright to allowing any abortions, that the states should have more say in regulating the procedure after the first trimester.

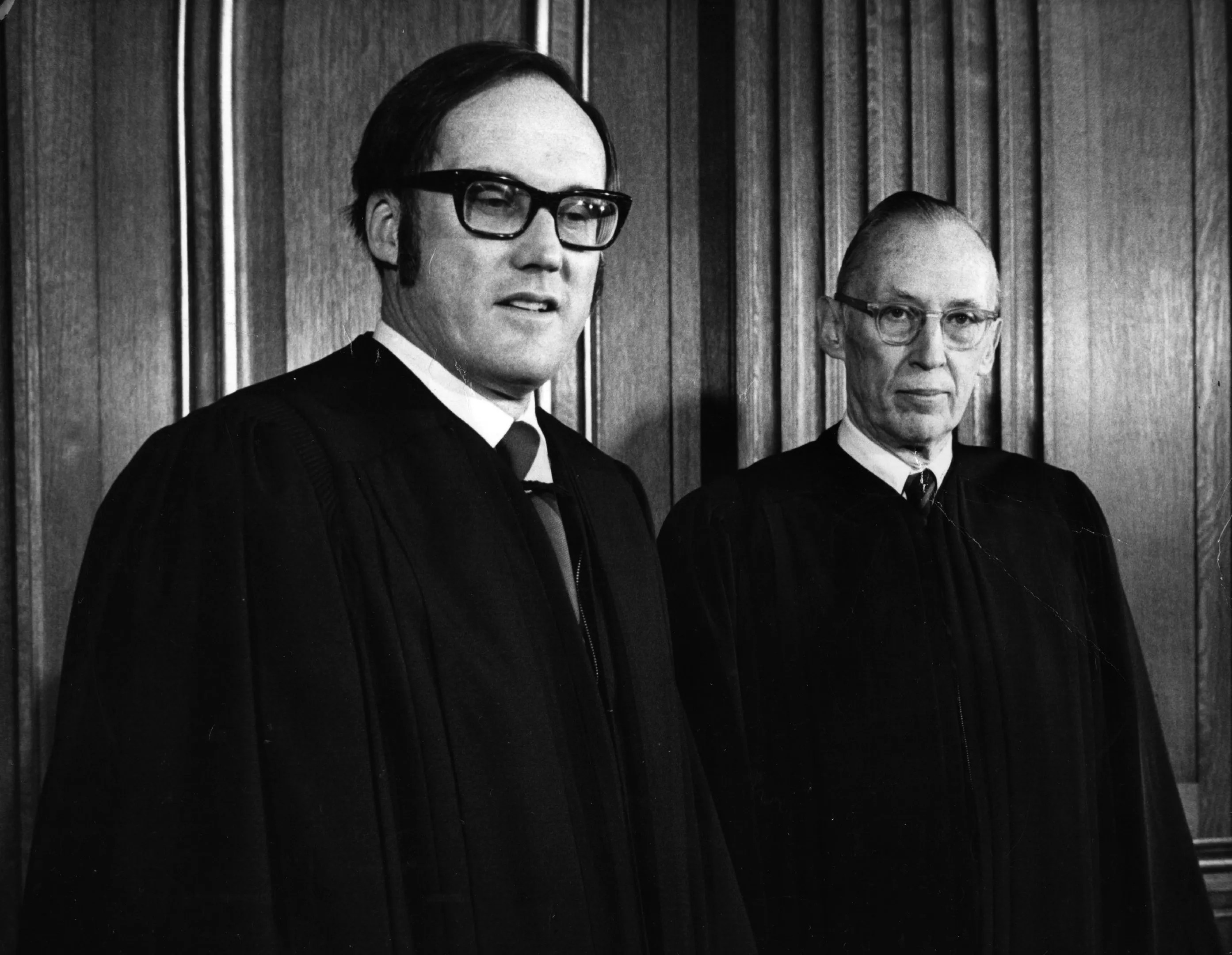

Newly sworn-in justices William Rehnquist, an attorney from Arizona (left), and Lewis Powell in 1972.

Keystone/Getty Images

But he was stuck there, wanting to draw the line at the first trimester.

That same day, Hammond sent more notes to Justice Powell regarding Blackmun’s most recent drafts of the majority opinion. He zeroed in on how to balance a woman’s right to privacy and the state’s “legitimate interest in protecting potential life.”

“If a line ultimately must be drawn, it seems that ‘viability’ provides a better point,” he wrote. “This is where Judge Newman would have drawn the line. It is consistent with common law history. Moreover, it comports with the rationale that the controversy over the finding of the time of beginning of ‘life’ is so great, and affects such intensely personal interests, that the [court] will not allow the state to make that judgment.”

Two days later, Powell passed that thought on to Blackmun in a letter. And the next week Blackmun responded that he still preferred the end of the first trimester and allowing the states to regulate abortion from that point on, but that he “could go along with viability if it could command a court.”

By December 11, Blackmun was becoming more convinced. In a memorandum to all the justices, he wrote, “Viability has its own strong points. It has logical and biological justifications. There is a practical aspect, too, for I am sure that there are many pregnant women, particularly younger girls, who may refuse to face the fact of pregnancy and who, for one reason or another, do not get around to medical consultation until the end of the first trimester is upon them or, indeed, has passed.”

Hammond jumped on that paragraph when he conveyed his reaction to Powell. What about the women?

“For many poor, or frightened, or uneducated, or unsophisticated girls the decision to seek help may not occur during the first 12 weeks. The girl might be simply hoping against hope that she is not pregnant but is just missing periods. Or she might know perfectly well that she is pregnant but be unwilling to make the decision – unwilling to tell her parents or her boyfriend.”

Within days, Powell reiterated his concern about the first trimester. Stewart weighed in with the same. Douglas sent a terse note saying he favored the first trimester. Brennan thought viability focused too much on the fetus instead of the woman. Marshall advocated for viability.

Blackmun decided.

In a memo to the conference, he wrote, “I have in mind associating the end of the first trimester with an emphasis on health” (because it was the safest time for a woman to undergo an abortion), “and associating viability with an emphasis on the State’s interest in potential life. The period between the two points would be treated with flexibility.”

The state, in other words, could exert more regulation during that period, and afterward, abortions could only take place in extreme emergencies.

The sausage was made.

Powell was satisfied, too, and decided to join with Blackmun on his final draft. He wrote a memo to Hammond that perhaps summed up the lot of the Supreme Court clerk.

“Although [Blackmun] gives credit in his memo of December 1 to others, I suggest that you are entitled – particularly in view of your education of me on the viability issues – to credit that is nonetheless substantial because it will never be recognized. I think I was perhaps the first to press for viability change,” Powell wrote.

The Leak

Roe v. Wade was supposed to be made public on January 17, 1973. But Chief Justice Burger decided to delay the release in deference to Nixon, who despite the ongoing trials of the Watergate burglars, was to be inaugurated into his second term on January 20 after a landslide reelection win.

In the previous week, Hammond had met with a law school acquaintance who was working for Time magazine – and he let slip “on background” what the majority opinion entailed, according to Robenalt’s book.

“It was typical of him,” Robenalt told me. “He was being friendly with a friend.”

The reporter, David Beckwith, prepared a story to be published January 22, 1973 (and dated January 29), which would theoretically come out days after the opinion’s publication.

The article ran without a byline, and it did not include leaked documents or any language in the opinion.

“Last week Time learned that the Supreme Court has decided to strike down nearly every anti-abortion law in the land,” it said after a lengthy lede. “Such laws, a majority of the justices believe, represent an unconstitutional invasion of privacy that interferes with a woman’s right to control her own body,”

Roe v. Wade was published the same day.

Nixon was furious at the leak, and especially with the reporter, who had also broken news on Watergate. He contacted Burger.

Hammond was opening Powell’s mail when he read Burger’s note about the leak – a scandal perhaps, but of limited scope. Hammond called Powell to confess, and once again offered to resign. Powell again refused and sent him to talk directly with Burger. The chief justice, according to Robenalt, scolded Hammond, but thanked him for his honesty and sent him back to work.

Shortly thereafter, Hammond moved on to the Justice Deparment to take part in prosecuting the other big legal story of the decade: the Watergate burglary and Nixon’s participation in it.

Pushback: Alito Strikes Back

In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a case from Pennsylvania called Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which some politicians and attorneys hoped would overturn Roe.

It set parameters on abortion law, including informed consent, waiting periods, parental consent in the case of minors, and a provision that the father of the unborn child grant consent as well.

The law cleared the Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, except for the husband-consent clause, which was deemed an undue burden on the woman and possible cause for domestic abuse. One judge on the three-judge appellate panel dissented on that issue – Alito, the future Supreme Court justice.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that lower court decision, although it balked at suggestions to overturn Roe. Instead, in an opinion co-authored by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, it gutted the trimester approach but kept the concept of viability. The majority also upheld the theory of privacy under the 14th Amendment – O’Connor, of Arizona, was steadfast in keeping government out of the bedroom – and cited stare decisis, the principle of upholding court precedence.

Sandra Day O’Connor was another conservative Supreme Court justice from Arizona.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Another Arizonan on the court, Rehnquist, stood on the side for overturning Roe.

Abortions in the U.S. peaked at 1.6 million in 1990, according to statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The last available tally showed about 630,000 abortions in 2019.

Washington D.C. and 16 states with the largest cities – mostly on the East Coast, along with California and Illinois – have passed legislation to keep abortion available. They will become medical destinations in coming years if Roe is knocked down, as appears likely.

And that is because of the same kind of selective math that allows a minority in the U.S. Senate to retain control, based on a majority of states instead of a majority of voters.

“[Twenty-six] states have expressly asked this court to overturn Roe and Casey and allow the states to regulate or prohibit pre-viability abortions,” Alito wrote in the leaked draft opinion for Dobbs, the pending abortion case before the high court.

Except for Texas, they are mostly states with smaller populations in the South and rural Midwest, plus Utah.

And of course, Arizona.

If the ruling goes, as is widely expected, it would be Alito’s revenge on the Planned Parenthood v. Casey opinion.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

But he’s right. Abortion is not mentioned in the Constitution and it has no legal precedence in American history. And as for court precedence, Alito implies, mistakes are mistakes, and should be corrected, and never mind that he and the other four judges in his majority cited stare decisis to dodge questions about Roe during their Senate confirmation hearings.

There is no concern for the women in Alito’s draft opinion, only for the fetuses they are carrying. As for due process, it doesn’t apply, because unlike issues like contraception, sex among consenting adults, and same-sex marriage, abortion “destroys potential life.”

“Roe was on a collision course with the Constitution from the day it was decided,” Alito wrote in the draft opinion, “and Casey perpetuated its errors, and the errors do not concern some arcane corner of the law of little importance to the American people.”

Roe and Casey were examples of “raw judicial power,” he wrote, and the only way to rectify that is through more raw judicial power. Exercising that raw power could happen any day.

History Repeats

In January 1973, days before Roe v. Wade was made public, Justice Blackmun prepared a statement to the public to explain the logic behind the opinion.

He anticipated the same questions that are being argued today, for and against, in the pending opinion that will likely invalidate Roe, noting that: doctors and religious groups could not agree on whether life began at conception, at viability or at birth; laws regulating abortion were already more than 100 years old; and women had a right to privacy over matters concerning her own bodies.

“We have concluded again, as the court has done before, that there is a right of personal privacy under the Constitution,” Blackmun wrote. “It is not spelled out in so many words, but the court has recognized this right before in many cases and in varying contexts. We feel that it is founded in the 14th Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action.”

He reiterated the need to balance that right with the state’s aim to protect health of both mother and fetus.

Then he added a disclaimer.

“In closing, I emphasize what the court does not do by these decisions,” he wrote. “I fear what the headlines may be, but it should be stressed that the court does not today hold that the Constitution compels abortion on demand. It does not today pronounce that a pregnant woman has an absolute right to an abortion. It does, for the first trimester of pregnancy, cast the abortion decision and the responsibility for it upon the attending physician. Thereafter, the decisions permit the state, if it chooses, to impose reasonable regulations for the protection of maternal and fetal health. And, after viability, they give the state full right to proscribe all abortions except those that may be necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.”

The same issues stand today. What’s different: compromise is no longer feasible.

It remains to be seen if the Roberts Court can find any common ground.

An Era Passes

It’s impossible to know if Larry Hammond would want to plow that field again.

He died in March 2020, at the age of 74, just as the coronavirus pandemic began to shut down the world. His memorial service would have been mobbed if it hadn’t been canceled at the last minute because of the pandemic. He had influenced so many people over the course of his career.

Most of us knew nothing about his influence in Roe v. Wade, or for that matter, about his work on Watergate.

As word spread that he was in the hospital and dying, so many friends wanted to visit that his assistant had to take appointments. Larry kept them, and he imparted his good advice as selflessly as ever. He was, as always, mostly concerned about fairness in the judicial system, and fairness of other sorts.

Hammond needed a lung transplant, but there were questions as to whether he was healthy enough to get one.

Friends recalled that he questioned whether he even deserved a transplant, thinking it should go to a younger person who had better chances of surviving. While awaiting a decision, Hammond died.

Dale Baich reflected on the loss.

“With Larry’s passing, there seems to be a void in the criminal defense community. His leadership is missed. There doesn’t seem to be another person who reaches across different constituencies to bring people together.”

Michael Kiefer, a longtime resident of Phoenix, was a senior reporter at The Arizona Republic and a staff writer at Phoenix New Times, and covered the U.S. Supreme Court.