Katya Schwenk

Audio By Carbonatix

After Ali Osman was shot and killed by Phoenix police officers on September 24, grieving family members requested to view the officers’ body camera footage of his last moments – all of the footage.

But for two weeks, they received nothing.

Then, on October 7, the Phoenix Police Department released limited footage of the killing in what it calls a “critical incident briefing.” The department releases similar briefings whenever a Phoenix police officer shoots someone. The briefings are highly edited compilations of body camera video and 911 calls, stitched together with a voiceover, and do not include all of the video captured by officers during an incident.

In the wake of Osman’s death, the Phoenix police practice of proactively releasing “critical incident briefings” in lieu of raw footage of an incident has come under scrutiny. Experts interviewed by Phoenix New Times were divided over whether or not the briefings are valuable, but they all said that departments should listen when a community demands greater transparency.

Phoenix police said all of the body camera footage of the September shooting was provided to Osman’s family within two weeks and will be released to anyone who requests it under the Arizona Public Records Law – although the agency regularly takes months to fulfill such requests. “We do release the full bodycam footage,” said Donna Rossi, a Phoenix police spokesperson. “And we did in this case.”

Quacy Smith, an attorney for Osman’s family, called the Phoenix police policy of releasing limited and edited bodycam footage “piss poor” and nothing more than an attempt “to try to tell a story and a narrative the way [the police] wanted to.”

“We have family here that has lost a family member,” he said during an October 7 press conference. “And two weeks later, you give them parts that you select – that you think is relevant.”

Ali Osman, a refugee from Somalia, was shot and killed by Phoenix police on September 24.

Courtesy Muktar Sheikh

‘Let’s Get This Motherfucker’

Osman, a 34-year-old Black man, encountered officers as they drove along 19th Avenue at sunset on September 24. Police said he threw rocks at two passing patrol vehicles and caused minor exterior damage, which is documented in the police briefing. The officers stop at a different location, briefly confer, and then return to the intersection where they saw Osman. In the body camera footage, one officer is heard saying, “Let’s get this motherfucker.”

As officers return and park within a few feet of Osman, video footage shows him throwing rocks at their vehicles. Seconds after exiting their vehicles, two officers shoot him with live rounds. At least one of the police cruisers was equipped with a shotgun loaded with bean bag rounds, according to attorneys for Osman’s family. The officers, assigned to the Desert Horizon Precinct on North 56th Street in Scottsdale, both have less than three years of experience with Phoenix police, according to the briefing video.

Osman’s family has filed an $85 million claim against the city over his death, signaling an impending lawsuit. The officers’ actions, according to the claim, were “extreme and outrageous.”

The killing has drawn a public outcry across Phoenix. On October 9, activists held a vigil and protest in Osman’s memory. The incident has deeply impacted the Somali and Muslim communities in Phoenix; Osman and his family came to Arizona as refugees from Somalia.

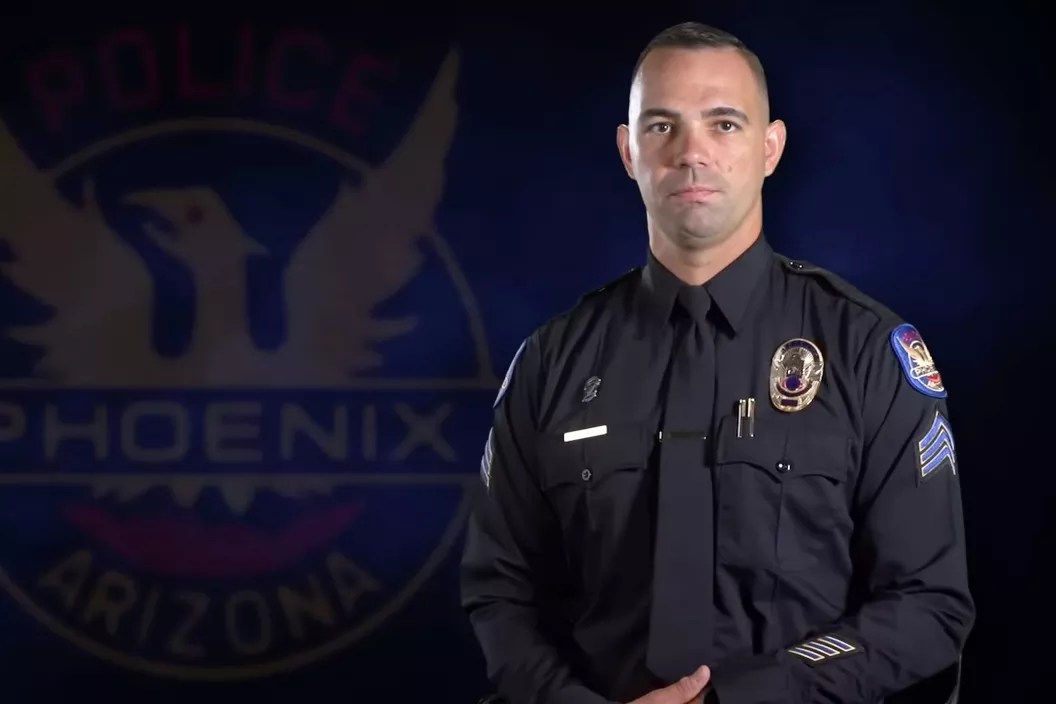

Questions remain about Osman’s death. Just 51 seconds of dispatch audio and less than two minutes of body camera footage – across all three officers originally involved in the encounter – were provided in the nearly seven-minute “critical incident briefing” released by police. Voiceovers by Sgt. Brian Bower, a police department spokesperson, made up the rest.

At one point in the briefing video, photos of several large rocks the police said were found at the scene of the shooting are displayed, though there’s no indication that the rocks were thrown by Osman. He was standing in a small strip of gravel along 19th Avenue. Samples taken by attorneys for Osman’s family show that most of the rocks of the area are an inch or two in length.

“How can we call this transparency?” said Percy Christian, an activist with Black Lives Matter Phoenix Metro, which has demanded that Phoenix police publicly release the full footage of the shooting death. The release of only small portions of the video was “really not giving the public and the city of Phoenix the opportunity to see and make up our own minds about the injustice that happened,” Christian added.

For Bryce Newell, a professor of media law and policy at the University of Oregon who has studied body camera policy extensively, the Phoenix Police Department’s policy of releasing packaged, selectively edited videos is an example of how law enforcement agencies attempt to control the narrative after a police killing. Newell said the “critical incident briefing” of Osman’s killing is “very polished.”

“Clearly, this is trying to frame and anchor a narrative in the way that the police department would like it to be framed,” Newell said. Still, he noted, Phoenix police did not attempt to justify the killing as overtly as he had seen done at other law enforcement agencies. At the end of the video, Bower noted that the incident is subject to an internal investigation and criminal probe.

Although Newell said that the release of bodycam footage can, in some cases, raise privacy concerns, he saw little reason for not releasing it in this incident. Osman’s death occurred in a public place, not in a private home. Osman’s family has advocated for the full footage to be released. “I don’t see much, from my perspective, that would make me want to say, well, we should hold back on giving access to everything right away. It seems to me that this would be a case where full access would be in the public interest,” Newell said.

Michael White, a criminology professor at Arizona State University who has worked with police agencies on body camera implementation, said that videos that provided additional context were generally “a good way to go.” Sometimes, important context is missing from raw footage, he said. Or there can be so much footage – if multiple officers are on the scene for hours, for example – that it can be difficult for people to sort through.

“I think there are a lot of upsides to it. The downside is that if you have a police department in a community where there’s some mistrust or antagonism, you’re going to have some community members who are going to view that as not being sufficient,” White said. “They’re going to want to see the whole thing, and the department’s refusal to release the whole footage may be viewed like they’re trying to hide something.”

Phoenix police Sgt. Brian Bower narrates a video that includes footage of a September 24 incident in which two officers shot and killed Ali Osman.

Phoenix Police Department

A ‘Slanted’ Narrative?

For some in Phoenix, the sense that the worst may not yet have been provided to the public rings true. Christian said that the dispatch audio that was released was disturbing on its own. “So I can’t imagine what the other things that they redacted are,” he added.

Jared Keenan, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, said he opposed the department’s policy of releasing limited bodycam footage and the often slow process of releasing the full footage through public records requests. “This undermines the entire purpose of bodycams,” Keenan said. “It’s hard to see this policy in any other way than as an after-the-fact way of justifying any use of force that they engage in.” The narrative, he said, was “slanted and one-sided.”

As media outlets, including New Times, wait for the department to process their requests for the full footage, the department’s own video has set the narrative. But the impending lawsuit over Osman’s death – and his family’s quest for answers – may ultimately change that.

So far, though, Christian and those who have been calling for police reforms in Phoenix for years are frustrated at the silence of city officials after the release of the video. “It shows how desensitized our city officials are to the slaying of Black men, unarmed men of color in this city,” he said.

“It doesn’t even pierce their hearts anymore,” Christian added.