Audio By Carbonatix

It was late evening on Thanksgiving Day, 1942, when hell came to Phoenix’s Black ghetto.

Machine guns bit into the night, lighting up the streets just east of downtown Phoenix with tracer bullets. Rifle and pistol fire from dozens of sources boomed simultaneously. The gunfire went on for hours, so continuous at one point that a witness said several minutes went by with no discernible break.

All the combatants were Americans, and members of a Black regiment were viewed as the aggressors. When the main battle died down, armored personnel carriers, hundreds of soldiers, and all available law enforcement officers descended on a 28-block area that was home to the city’s Black population, hunting for the Black soldiers involved and spraying machine-gun fire into the homes of Black citizens who wouldn’t immediately give up their friends.

No one knows for certain how many people died in the firefight and “mop-up” operation. It could have been as few as three or far more.

History calls the event the Thanksgiving Day Riot, or the Phoenix Massacre, though it wasn’t exactly a riot and whether it was a massacre is up for debate. Some say the real massacre didn’t happen until the unit transferred again to Mississippi.

Contemporary and modern historians are reluctant to label the bloody incident as a race riot because it differed from the more direct style of interracial violence seen the following year in Detroit and Mobile, Alabama, which involved racist attacks on Black people in addition to rioting.

Yet interracial tension was at the root of the problem and how it was handled by authorities. The Phoenix Thanksgiving Day Riot occurred during an era of extreme segregation that resembled a caste system between Black and white people. Today, Black Lives Matter activists and supporters see similar underpinnings in their fight against police brutality and lingering systemic racism. At the same time, the chaos of the pandemic has helped fuel social unrest much as World War II did back in the 1940s.

Interestingly, the action-packed tale and a bizarre conspiracy theory that followed it are little remembered by most citizens of Phoenix today. Few articles in mainstream publications have been published about it, and many details, like the true death toll or whether everyone arrested deserved punishment, are yet to be discovered.

“Most people I know don’t even know that story,” said Rodney Grimes, an amateur scholar of Black history and longtime Phoenix resident. Grimes has a personal link to the riot, he said: His great-uncle, Joseph Island, one of the first Black Phoenix police officers, helped the first person to be injured in the incident, a woman whose victimization led to the intense gunfight.

The Bad Old Days

More than 4,200 Black people lived in Phoenix in 1942, or about 5 percent of the city’s total population. (It’s just under 7 percent now.) Many struggled to survive in substandard conditions, with most never able to fully participate in the greater community. The late Phoenix historian Brad Luckingham describes some of the appalling scenes of south Phoenix in his 1994 book, Minorities in Phoenix, through the eyes of Father Emmett McLoughlin, a Catholic priest who helped the Black community in the 1930s and ’40s:

“One poor area … between the warehouse district and the city dump in southwest Phoenix was … ‘permeated with the odors of a fertilizer plant, an iron foundry, a thousand open privies, and the city sewage disposal plant,” Luckingham writes, quoting McLoughlin. “‘Its dwellings for the most part were shacks, many without electricity, most without plumbing and heat. They were built of tin cans, cardboard boxes, and wooden crates picked up by the railroad tracks … In these shacks, babies were born without medical care; they often died because of extreme temperatures (up to 118 degrees) in the summer or froze to death in winter.'”

Segregation ran deep in Phoenix, with Black people expected mainly to perform menial labor or domestic work. They were banned from most hotels, movie theaters, restaurants (except as workers), clubs, swimming pools, and, in fact, prohibited from living or even walking in most parts of the city. Most lived between Washington Street and Buckeye Road, and between Central Avenue and 16th Street.

Much of the action in the 1942 “riot” occurred in the neighborhoods around Eastlake Park at 16th and Jefferson streets.

Ray Stern

That area and other Phoenix slums had been borne out of the Wild West days; where whorehouses and seedy gambling establishments were tolerated, Black families might be tolerated to dwell, too. Over time, the white authorities closed up most of the whorehouses and illegal poker tables, and the Black communities remained, often with remnants of the illegal trade that the majority of Black residents wanted nothing to do with.

Phoenix had evolved as a solidly racist city. The Ku Klux Klan paraded openly in Phoenix in the early 1920s, its membership filled by town leaders including the mayor. Each year, the city held an annual and free children’s picnic that drew thousands of people from all over the Valley. Black kids, and children of Hispanic, American Indian, or Asian parents, were warned to keep out.

When World War II came, life changed fundamentally for Americans. Phoenix became a large military base, its city streets crammed with military personnel. The newcomers caused retail businesses and restaurants to thrive, but the war effort brought changes that felt to many residents, especially the white male power base, like someone had opened a Pandora’s Box.

As Arizona State University history professor Eduardo Pagán explained to Phoenix New Times, women emerged from domestic life to become essential workers, fathers weren’t home, kids were unsupervised. And, he said, a shift in attitudes about race plus the requirements of the war caused more mixing between white people and those of other races or ethnicities (except for Asians, who were still excluded during the war).

“In 18 months, society had been completely upended… always a recipe for social unrest,” Pagán said.

“Actual racial violence was common at the time throughout the United States,” said Paul Hietter, a Mesa Community College history professor. “For the first time, you’ve got a huge intermingling of races you didn’t have before. People sought equality, and there’s going to be hostility among the people of Phoenix.”

In the same way the novel coronavirus pandemic has destabilized so many American lives, so too did the war effort. But Hietter pointed out one major difference between our current era and 1942: President Franklin D. Roosevelt was trying to unify the country despite the racism, while President Trump actively tries to disunify the country.

“That’s the most mind-boggling thing about this time,” he said.

Mistreated Troops

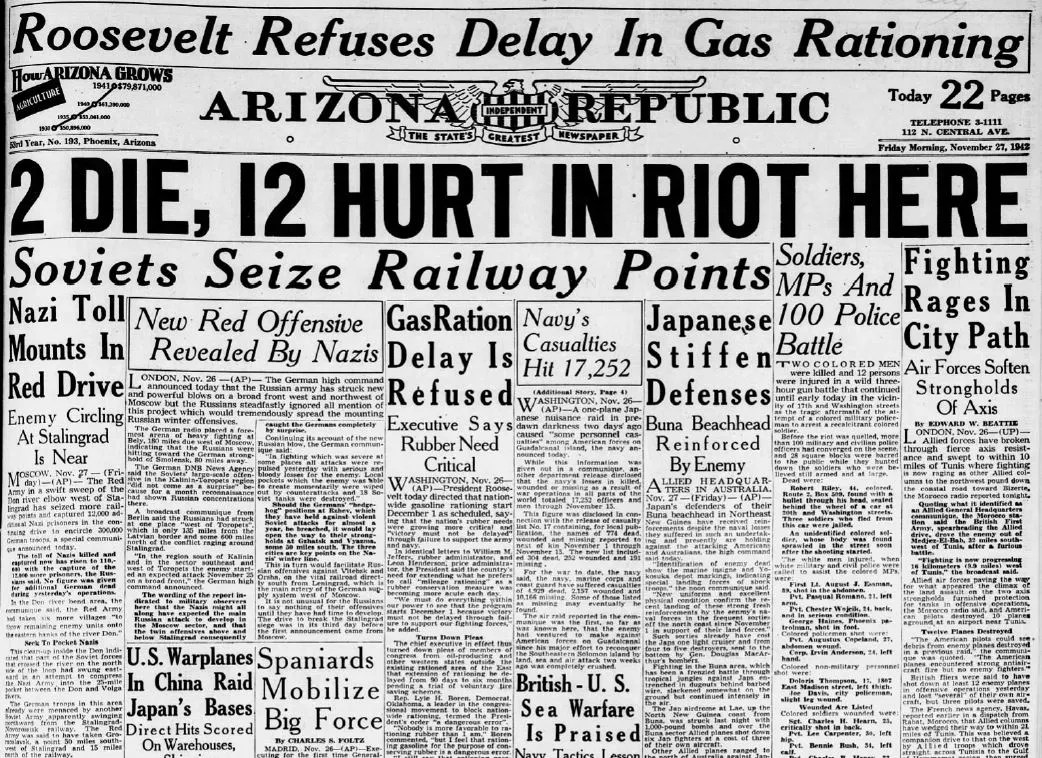

Into the chaos of what Hietter calls “the extraordinariness of the times” stepped the 364th Infantry Regiment, a segregated Black unit from Lousiana formed from the leftovers of another unit.

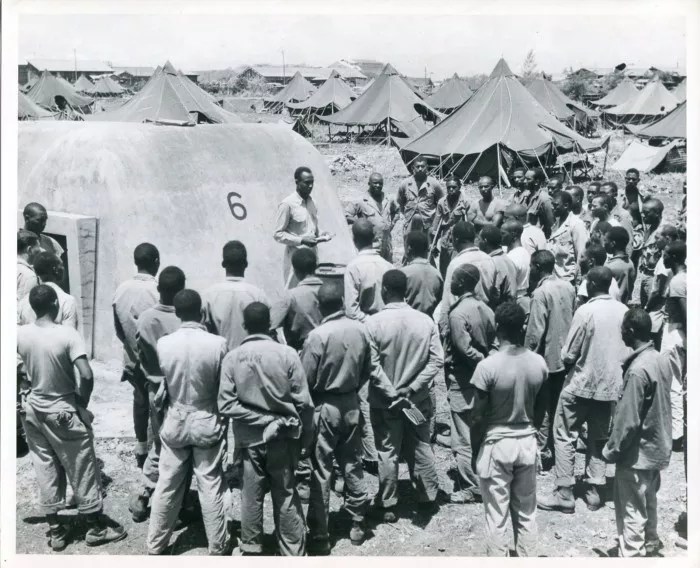

The regiment had been implemented a year earlier in 1941 as the 367th regiment, according to the “Employment of Negro Troops,” a 1965 book by Ulysses Lee commissioned by the Army. But one arm of the regiment was sent overseas in total secrecy, leaving the rest of the new troops in need of training. They were transferred to Phoenix to help guard German prisoners of war at a concentration camp in Papago Park. Before the riot, the book says, the 364th was involved in a lesser, though serious, disturbance when 500 of the men refused an order to disperse. The book doesn’t detail that incident.

While the 364th is at times depicted as a rowdy group of fellows, their second-class citizen status undoubtedly weighed on them and other Black troops at all times. The great experiment of integration into the armed forces in the United States was viewed with cynicism and distrust by many. A survey showed that after the attack on Pearl Harbor, “full support of the war” by Black Americans fell short because of the “bitter” fact of discrimination in the military.

“They cherish a deep resentment against the vicious race persecution which they and their forbears have long endured,” a Black newspaper in New York opined, as Lee’s book relates. “They feel that they are soon to go overseas to fight for freedom over there. When their comparative new-found freedom is challenged by Southern military police and prejudiced superiors, they fight for freedom over here.”

The 364th regiment on parade in downtown Phoenix.

As Truman Gibson Jr., a lawyer and former presidential aide, wrote in the 2005 book, “Knocking Down Barriers: My Fight for Black America,” members of the 364th were housed in “tar-paper shacks” in Papago Park that became “sweltering furnaces” in summer. An Army investigation later determined the 364th was given “inadequate clothing and footgear.”

Gibson Jr., who had visited the unit in Lousiana after receiving complaint letters from some of the soldiers’ parents, wrote that the unit’s training officers were racists.

On top of all of that, a new Army policy meant that military police (MPs) who were in the 364th were replaced with independent MPs, according to a 1987 Arizona Republic article. Apparently, the Army suspected the MP members of the 364th of illegal activities. Two of the new MP battalions, one white and one Black, were assigned to the area, and the previous MPs were returned to regular duties in the 364th, which they resented.

(Enlisted men throughout the Army’s history have sometimes distrusted MPs, so some of those feelings likely transcended race.)

On top of this powder keg of simmering emotion in the ranks, on top of the everyday struggle with racism, alcohol also helped light the fuse: The 364th’s commanding officer gave the unit all the beer they could drink for Thanksgiving Day, Gibson Jr’s account says, “and handed out plenty of passes. Some of the soldiers naturally went into town.”

Shootout

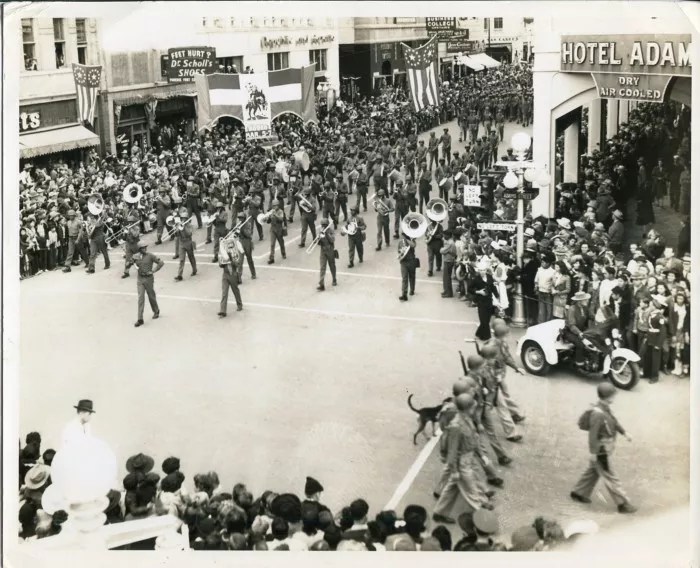

What happened next is well-detailed in the Arizona Republic’s November 27 and 28, 1942, editions, which can be accessed for a fee by an online site. On the day after Thanksgiving, a day full of intense World War II news, the paper’s top headline blares, “2 DIE, 12 HURT IN RIOT HERE.”

The incident began at about 11 p.m. when a soldier at a bar near 13th and Jefferson streets got angry at a woman and hit her in the head with a bottle. (Grimes told New Times his uncle took the woman home.) A Black MP tried to take the soldier into custody and fired a shot that wounded the soldier. An “uproar” ensued. That went on for 15 minutes or so, with MPs and soldiers both getting “roughed up.” Another altercation between MPs and soldiers flared up a couple of blocks away.

The riot dominated the front page of the Arizona Republic on November 27, 1942.

newspapers.com

Army authorities ordered the 364th to return to their base at Papago, and about 150 or so lined the street on Washington near 17th Street to board a bus. More MPs with guns showed up, causing the soldiers to break ranks and become “excited.” Rumors spread that members of the 364th were being gunned down.

While the MPs were trying to get control of the 364th, several of the soldiers took a car back to Papago and raided the armory there, taking rifles, pistols, and a fully automatic Tommy gun. The car drove up to the scene behind MPs in a jeep.

“Bullets sprayed in all directions, and the long rank of soldiers scattered widely,” the Republic article states, describing the scene as turning into a “minor battlefield.”

Up to 100 members of the 364th took part in the shootout.

Robert Riley, a 44-year-old Black man who lived in Phoenix, was found dead, shot through the head, in a car. Three Black men seen fleeing from the car were arrested. A Private Geoge Hunter, originally of New York City, had been found dead on a street. A white lieutenant, positioned behind cover with two other men, was shot between the eyes and later died.

After identifying the dead men, the Republic named “the white men injured when white and military civil police were called to assist the colored MP’s.” Then the wounded Black MPs were listed, then wounded Black civilians, and finally the wounded Black soldiers.

Doloris Thompson, a 17-year-old girl, was the youngest person reported injured in the fight. She was shot in the thigh. Numerous others took bullet wounds to various parts of the body, and two were listed in critical condition in the aftermath. Some people were pinned down by crossfire for hours, a later report said.

“The only white persons injured reached the scene long after the trouble started,” the Republic duly noted for its white readers, “and were all military policemen who were asked to help the colored MPs.”

“All available law enforcement officers” in Phoenix were called in to assist military police, Luckingham’s book states.

The dozens of armed soldiers from the 364th, outnumbered as more outside soldiers and law officers poured onto the scene, scattered into the neighborhood.

The army and police cordoned off a 28-block area, reportedly putting a machine gunner at 16th and Jefferson streets at the edge of the cordon to watch for stragglers. Using armored personnel carriers, the hunters flushed out suspects hiding in friends’ homes.

Luckingham quotes a witness as saying, “They’d roll up in front of these homes and with the loudspeaker they had on these vehicles, they’d call on him to surrender. If he didn’t come out, they’d start potting the house with these fifty-caliber machine guns that just made a hole you could stick your fist through.”

Such use of extreme firepower on citizens’ homes today would likely result in multi-million-dollar settlements with the government. Back in 1942, authorities viewed the attack on the Black neighborhood as nothing special. There’s no report of anyone challenging it in court.

Questions Remain

The night’s official death toll was later bumped up to three. But rumors put it as high as 19, says the 1987 Republic article by James Cook, who interviewed Gene McLain, the Republic reporter who covered the incident in 1942, and an unnamed retired Phoenix police officer. The dead supposedly included “civilians killed in their homes and on the streets,” according to Cook’s unnamed source. The official number of dead and wounded “was never changed,” he said.

About 180 African American soldiers were rounded up in the wake of the violence, but only “18 or 20” of those were identified as the instigators, and the rest were released. Fifteen or 16 members of the 364th were court-martialed; the retired cop claimed he testified against several rioters. The 1965 book by Lee states that each man was sentenced to 15 years in prison. One Black soldier, Joseph Sipp, received the death penalty but had his sentence commuted by President Roosevelt. The amount of prison time the men actually served is unknown; Hietter said he is skeptical they served 15 years for the riot.

The neighborhood where the incident occurred contains new development as well as older, dilapidated properties.

Ray Stern

Whether these prosecutions represent what we think of today as justice is unknown. A detailed, scholarly review of the Phoenix incident has yet to be conducted.

The story of the 364th got weirder when it left Phoenix. The perceived trouble-making regiment was transferred to Camp Van Dorn in Mississippi, where another major disturbance occurred. According to a conspiracy theory popularized in the 1998 book, “The Slaughter: An American Atrocity,” 1,200 Black soldiers were executed, Nazi-style, by white troops.

The U.S. Army became so disturbed by the conspiracy theory that in 1999, it published a comprehensive report saying that the executions never happened and that the men of the 364th, for the most part, can all be accounted for in Army paperwork. But good conspiracy theories don’t die if there’s money to be made. In 2001, the History Channel aired a segment still enjoyed by conspiracy theorists about the 364th and the alleged killings.

Claims of a mass execution and cover-up aren’t generally believed. But the history of the 364th regiment is still worth exploring.

“There was no justice for the victims, the community was traumatized, and the lasting effects include fear and deep distrust of law enforcement (who joined in the ‘riot’) and the criminal justice system,” said former ASU professor Matthew Whitaker, who resigned from his position as co-director of ASU’s Center for Race and Democracy in 2016 after allegations of plagiarism, and is one of the few scholars in Arizona who has studied the riot. He now runs a consulting group. “One must also consider what constitutes a ‘riot.’ Is it a riot when uniformed Black people defend themselves against White members of the military, and law enforcement storm into a Black neighborhood and unleash military weapons and mayhem? I argue that there is a difference between a riot and a mass hate crime.”

The subtext of the 78-year-old incident – anti-Blackness, systemic racism, and abuse of authority – are all familiar topics in the post-George Floyd era. For the 364th, it was what Professor Pagán sees as “us against them” tension – between the troops and their superior officers, and between Black and white people in Phoenix and the rest of America.